One of the strangest chapters in the history of the ancient panel portraits from the Fayum region in Egypt took place in the 1930s and 1940s in Nazi Germany. In a process that involved archeologists, art historians, scholars of ancient Judaism and early Christianity, and geneticists, the panel portraits became scientific, "racial" evidence in the study of ancient and contemporary "races," and in the "biological history" of ancient Egypt and ancient and contemporary Jews. How did ancient portraits come to be viewed as bearing importance on twentieth century Jews in Poland? What visual and material processes did the panel portraits undergo in the process? And what intellectual and political ends were they intended to serve?

The first scholar who identified some of the portrayed persons as Jews was, interestingly, the 19th century German-Jewish Egyptologist and writer Georg Ebers. For him, these panel portraits revealed the high social status of Jews in the Hellenistic period (in which the portraits were initially thought to have been created, though they have since been dated to the Roman Period). The British archaeologist Flinders Petrie was the first who used the portraits as scientific evidence for his discussion of "racial mixture," closely related to both the discussion of "race" in terms of "racial purity" and "racial degeneration" in late antiquity. After 1900, the portraits were increasingly discussed by archaeologists and art historians, and, in these discussions, anti-Jewish biases could often be sensed. Yet the identification of portraits with Jews tended to focus on five to ten out of many panel portraits from the Roman Period. In the course of these discussions, portraits that Ebers and Petrie initially identified as Jewish, were seen instead as illustrating "pure Greek" or "pure Roman" and similarly portraits that were previously considered "pure Greek" or "pure Roman" were identified as "Jewish."

The process by which the Fayum panel portraits came to be used as racial scientific evidence with regard to contemporary European Jews involved not only archaeologists but art historians as well. While dating the collection in 1933, art historian Heinrich Drerup determined the Jewish identity of the person in a panel portrait (now in Würzburg, Germany) based on comparisons to contemporary antisemitic caricatures.

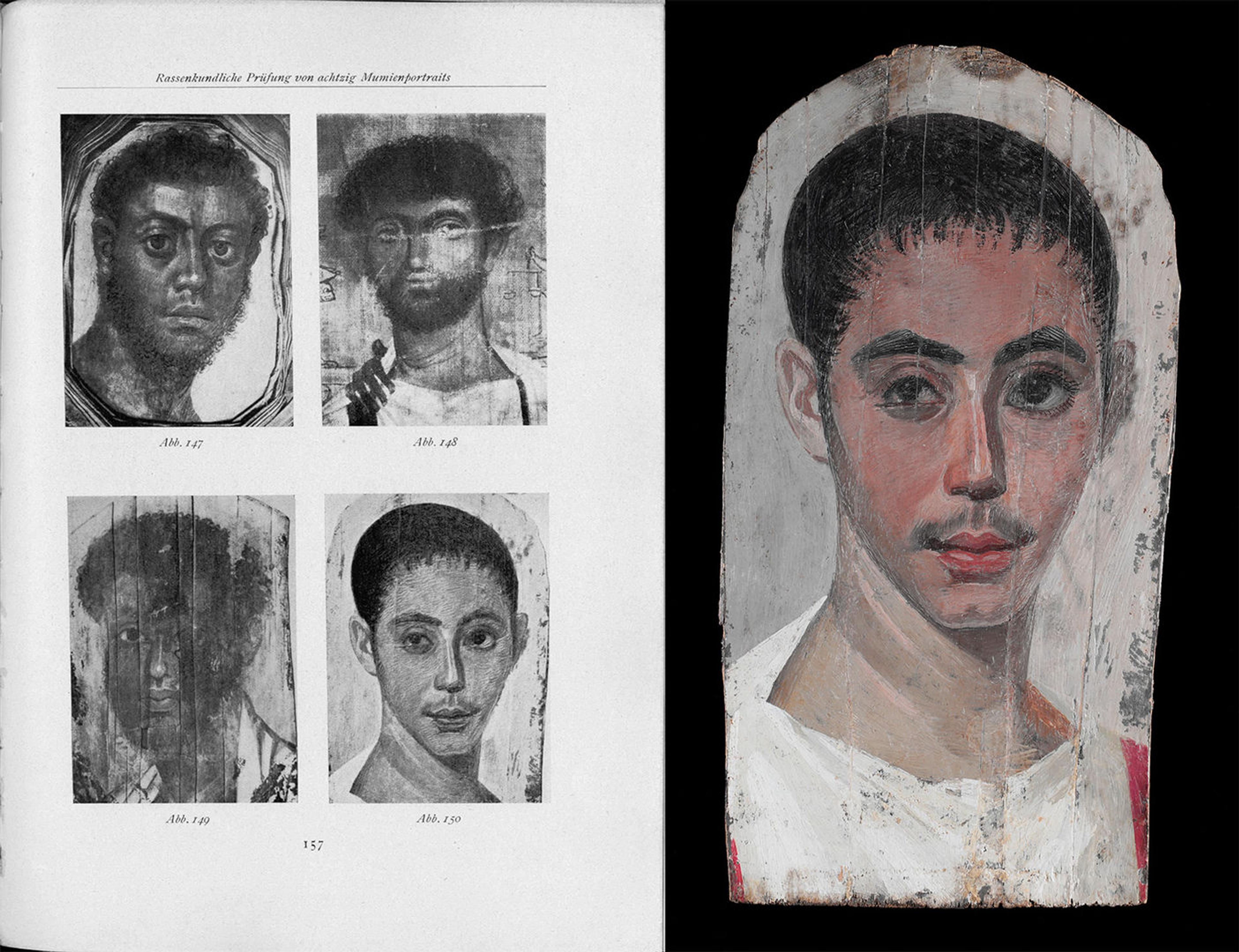

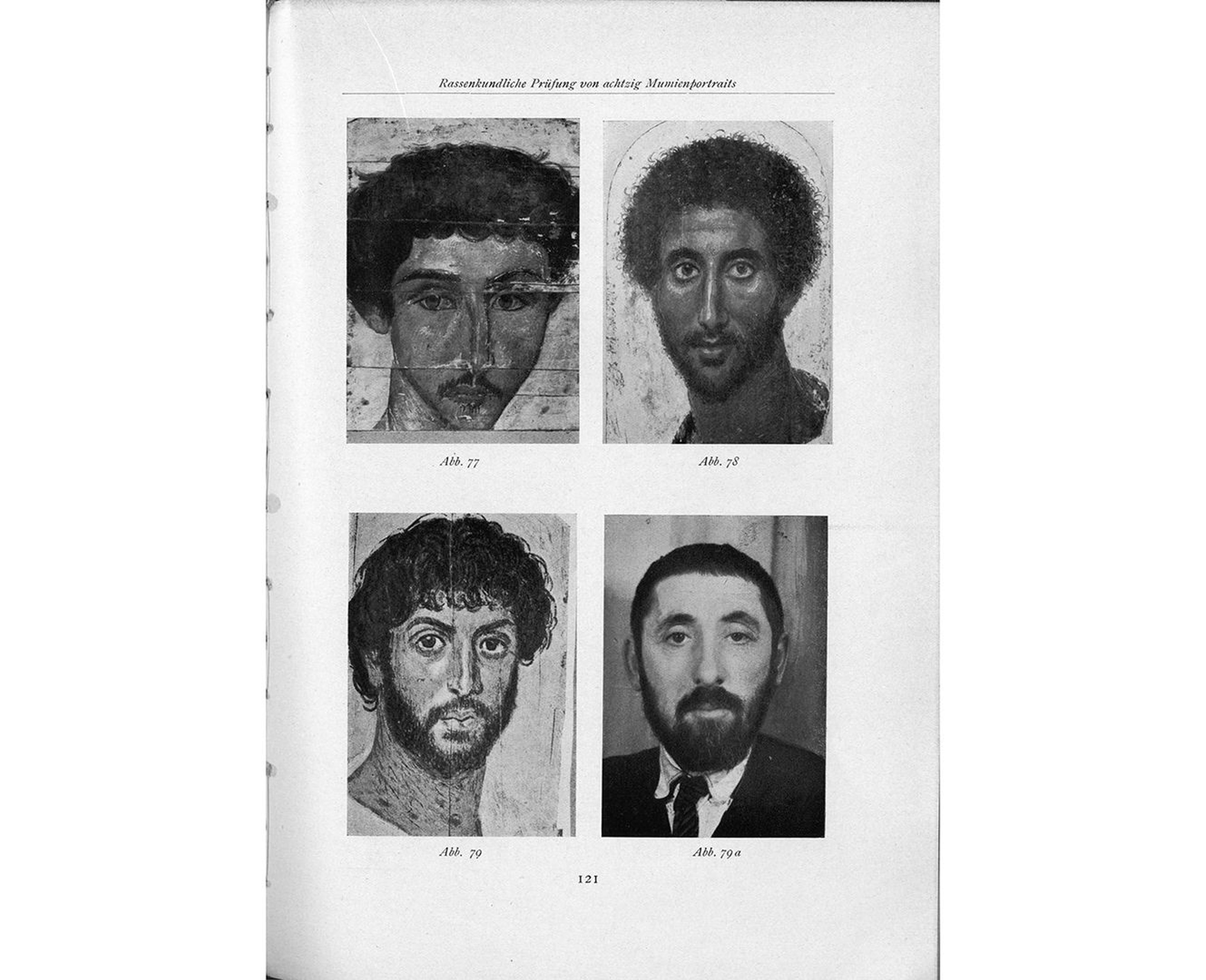

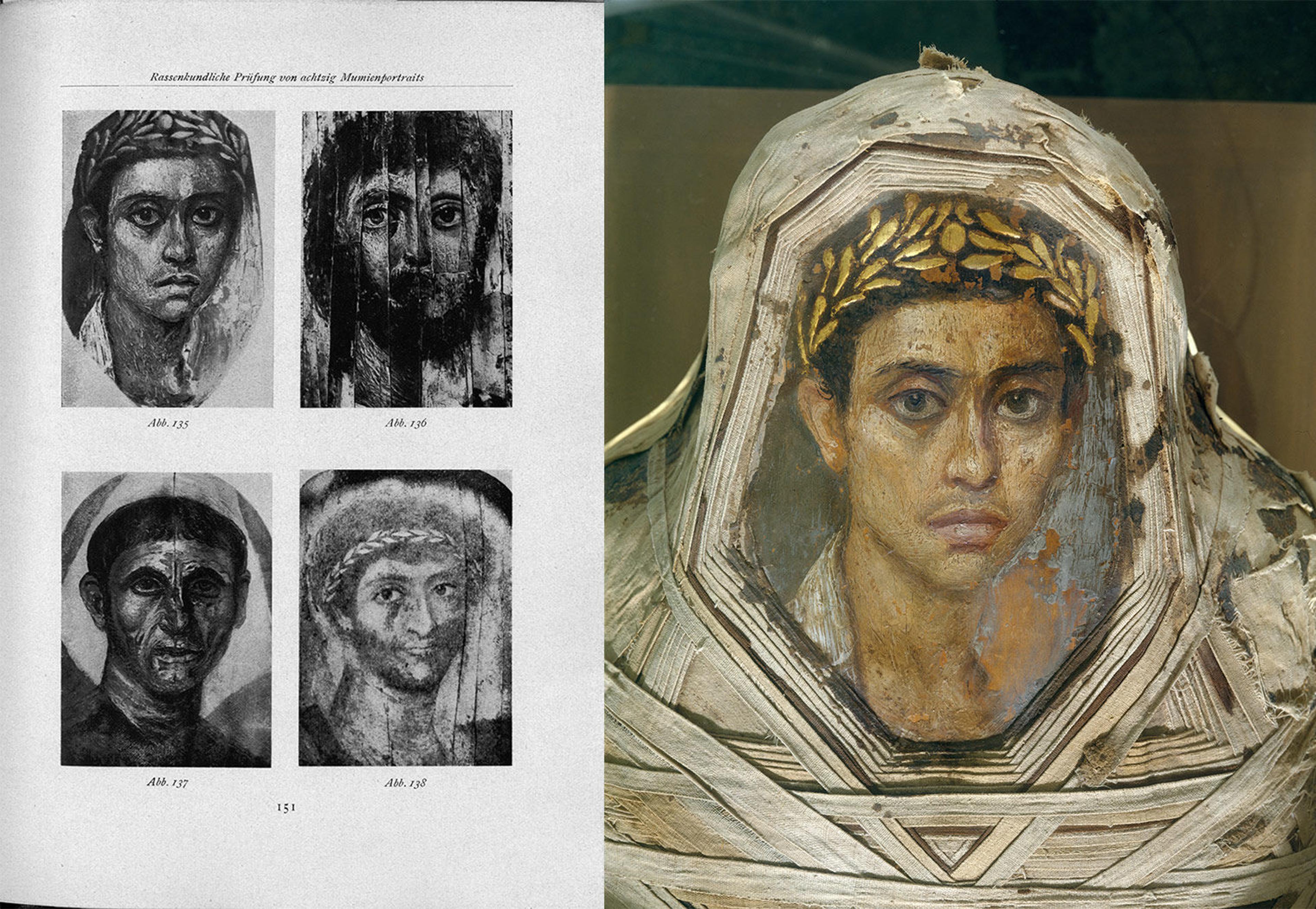

While Drerup made this determination based on the identification of the "Jewish expression" found in contemporary antisemitic caricatures, the gradual incorporation of Fayum panel portraits into the racial-scientific literature was on the whole based rather on the assumption that the portraits were realistic and representational, like scientific, "racial photographs." A related nuance pertains to then contemporary assumptions found in art history/Egyptology, which contrasted "Egyptian realism" with classical "Greek idealism," the former created realistic portraits as part of their attempt to preserve the integrity of the body whereas the latter aestheticized it. Indeed, to employ them as racial photographs, they treated the portraits as racial photographs. In the process of being incorporated into professional and popular scientific publications on "race," the portraits were brought closer to the photographic orbit in general and to the conventions of scientific, racial evidence in particular: highly colourful portraits were photographed and reproduced in standard black and white. These photographs were then resized so that the panel portraits, which are greatly irregular in size and shape, appeared instead to have a standardized shape and size. The portraits were cropped, centered, and scaled. The diversity of the materials on which the portraits were made was photographically supressed and diminished. Their use leapt over time, space, as well as their material and assumptions about their production, use and intention. Serialized as "racial type" photographs, the portraits were transformed into photographic evidence in the scientific discussion of "race."

Fayum panel portraits were employed in this context by the most celebrated theoretician of "race" in Weimar and Nazi Germany, Hans. F.K. Günther, whose books circulated in millions. But the most comprehensive and vile use of the portraits is found in a book co-authored by one of the most prominent German scholars of ancient Judaism and early Christianity, Gerhard Kittel, and one of the most famous contemporary German geneticists, Eugen Fischer.

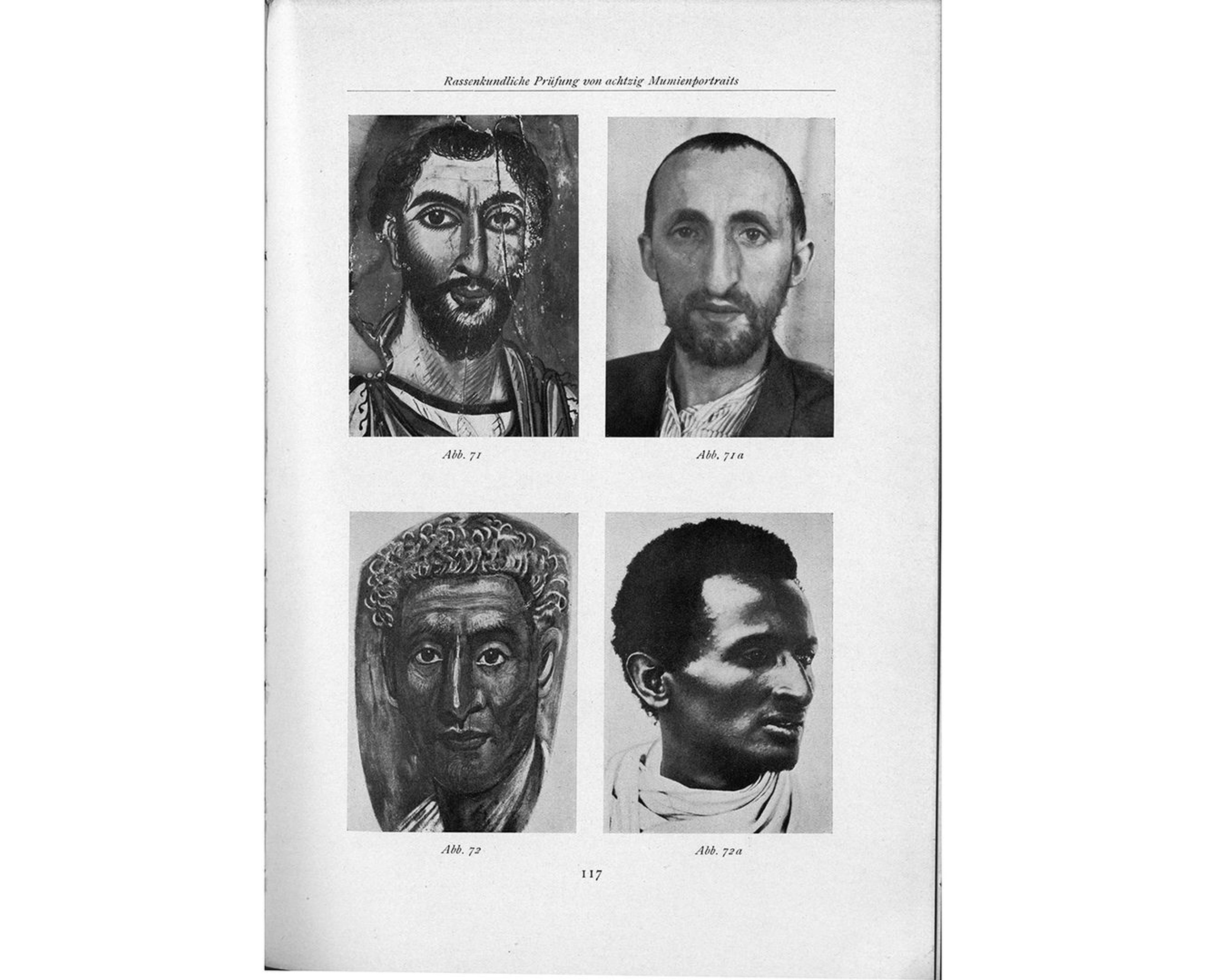

The Antike Weltjudentum was written in 1942 at the height of German military success, when the German army appeared invincible and after the majority of European Jews had already been killed. However, the book only appeared in print shortly after the German defeat in the battle of Stalingrad, which marked the military turn of events in WWII. A deeply racist and antisemitic study combining scholarship and propaganda, the book was a study of ancient Jewry which simultaneously celebrated the then almost complete eradication of the "Jewish race" from the face of the earth. Kittel and Fischer included tens of photographic reproductions of Fayum panel portraits, in black and white, cropped and centered. Sometimes, they were organized alongside photographs of Africans (to emphasize in their terminology the "negroid" features of ancient and contemporary Jews) and anthropological photographs of Jewish men taken by Fischer’s assistants in the ghetto of Lodz/Littzmanstadt in occupied Poland in the fall of 1940, to demonstrate their shared racial composition.

Page 117 of the book is laid out to emphasize the similarity between an ancient Egyptian and a Jew from Lodz, implying the permanent essence of the Jewish phenomenon as primitive and alien across time and space (Fig. 12). The photographic layout on the right-hand page is accompanied by short explanations on the left-hand page. Fischer describes his figure 71, under the heading of the Oriental and Near-Eastern races, as "Near-Eastern nose, narrow, long Oriental facial form, thick, fleshy lips. On the whole a very crude type (sehr grober Typ)." And 71a is described as: "Very similar type: Jew from Lodz, photographed 1940." (116)

With the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, the use of photographs for the scientific study of "race" declined instantly and sharply. This decline was faster and sharper than other media such as statistics or the sciences of "race" as a whole. The Fayum panel portraits were never used again as "evidence" in the scientific study of Jews, but for many years publications such as The Antike Weltjudentum, and the scientific methods on which they were based, were largely considered simply controversial chapters in the history of science. It was only decades after the demise of "racial photography," following long and arduous historical research and transformations in the public understanding of "race," that these publications were redefined as, simultaneously, malicious expressions of murderous racist and antisemitic ideology and propaganda.