During the period from 1000 to 1400, in spite of great political instability largely due to Turkic and Mongol armies sweeping through the region, Iran becomes one of the most important cultural and artistic centers in the Islamic world. Under outstanding patrons, Iranian artists demonstrate tremendous ingenuity and technical skill. Their creations are among the masterpieces of late medieval Islamic art and architecture.

Iran, 1000–1400 A.D.

Timeline

1000 A.D.

1100 A.D.

1100 A.D.

1200 A.D.

1200 A.D.

1300 A.D.

1300 A.D.

1400 A.D.

Overview

Key Events

-

ca. 900–1100

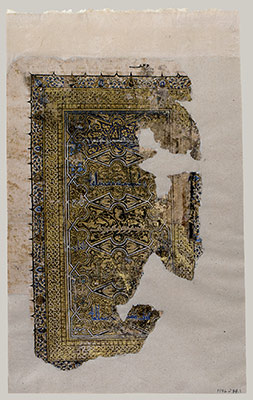

Particularly fine ceramics, metalwork, and relief-cut glass are produced in Iran during this period. The artists in Nishapur develop very distinctive ceramics in which slip painting beneath a transparent glaze produces a durable surface on earthenware pottery and allows for much creativity.

-

945–1055

The weakened Abbasid caliphate, its political power effectively limited to Iraq, is controlled by the Iranian Buyid dynasty, supporters of Shi‘a Islam. The influence of the Abbasid caliphs is limited to the moral and spiritual spheres, as the heads of Orthodox Sunni Islam.

-

ca. 950–1150

Despite political instability, the period is a critical point in the intellectual, philosophical, and scientific life of Iran, one in which the active figures are some of the most influential scholars in medieval Islam, including al-Biruni (973–1048), astronomer and polymath, Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037), physician and philosopher, and al-Ghazali (1058–1111), theologian and mystic. The Latin translations of Avicenna’s works have a tremendous effect on the development of philosophy and medicine in Europe.

-

ca. 1000–1100

Funerary monuments are prominent among architectural developments during this period. Of the surviving examples, the Gunbad-i Qabus near Gurgan (1006–7), as well as the mausolea of Sangbast (1028), Damghan (1056), Khargird (1087), and Kharraqan (1067 and 1093) are particularly noteworthy.

-

1010

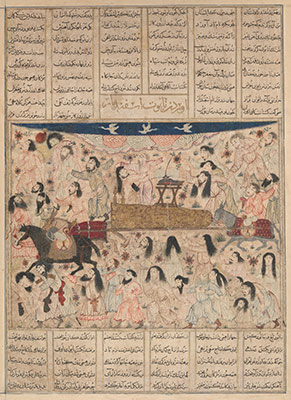

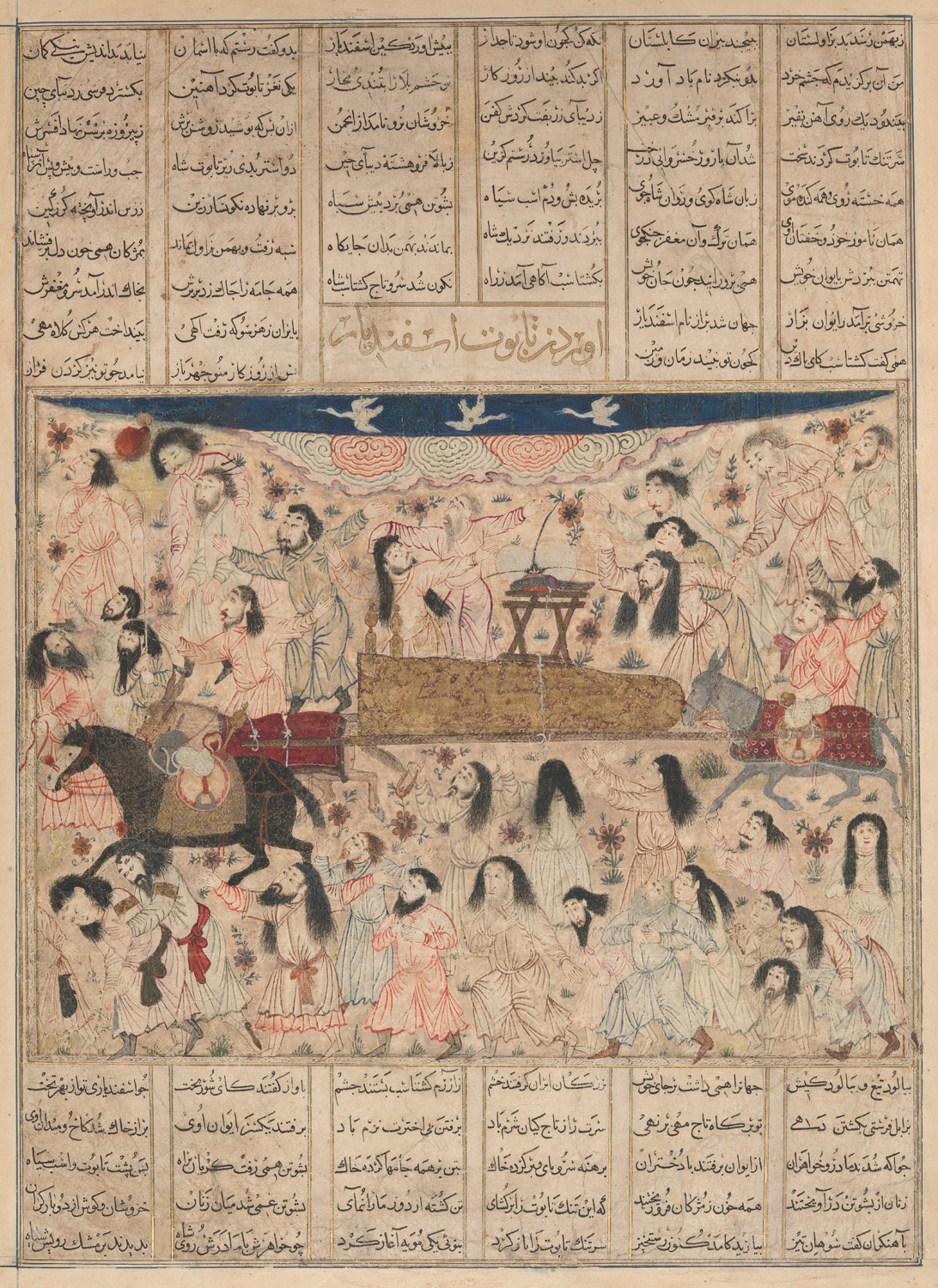

The Shahnama (Book of Kings), the Iranian national epic, is completed by the poet Firdausi (935–1020) and dedicated to the great Ghaznavid ruler Mahmud (r. 998–1030)

-

ca. 1040–1157

Following their defeat of the powerful Ghaznavids at the Battle of Dandanakan, the Seljuqs, a Turkic dynasty of Central Asian nomadic origin, become the new rulers of the eastern Islamic lands. Their sovereignty is strengthened with their takeover of Baghdad, which puts an end to Buyid rule (1055) and establishes the Seljuqs as the new protectors of the Abbasid caliphate and Sunni Islam. Though their vast empire encompassing all of Iran, Iraq, and much of Anatolia is relatively short-lived, the Seljuq cultural efflorescence continues well beyond the sultanate’s political influence. The creativity in the arts and architecture during the Seljuq period has a notable impact on later artistic developments.

-

ca. 1073–1092

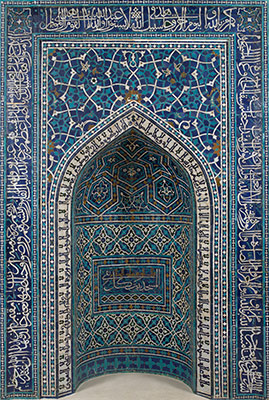

The transformed congregational mosque in Isfahan, for which additions are commissioned by Nizam al-Mulk (r. 1063–92) and Taj al-Mulk, two Seljuq administrators, for Sultan Malik Shah (r. 1072–92) and his wife Terkan Khatun, is the most celebrated and influential Seljuq monument.

-

1221–1256

Following conflict with the Khwarazmshah dynasty (1157–1221), the Mongols sweep through and take control of Iran. Mongol conquests devastate the region and affect the balance of artistic production. However, in a short period of time the control of most of Asia by the Mongols—the so-called Pax Mongolica—creates an environment of tremendous cultural exchange; Chinese and other East and Central Asian influences are seen in Islamic art.

-

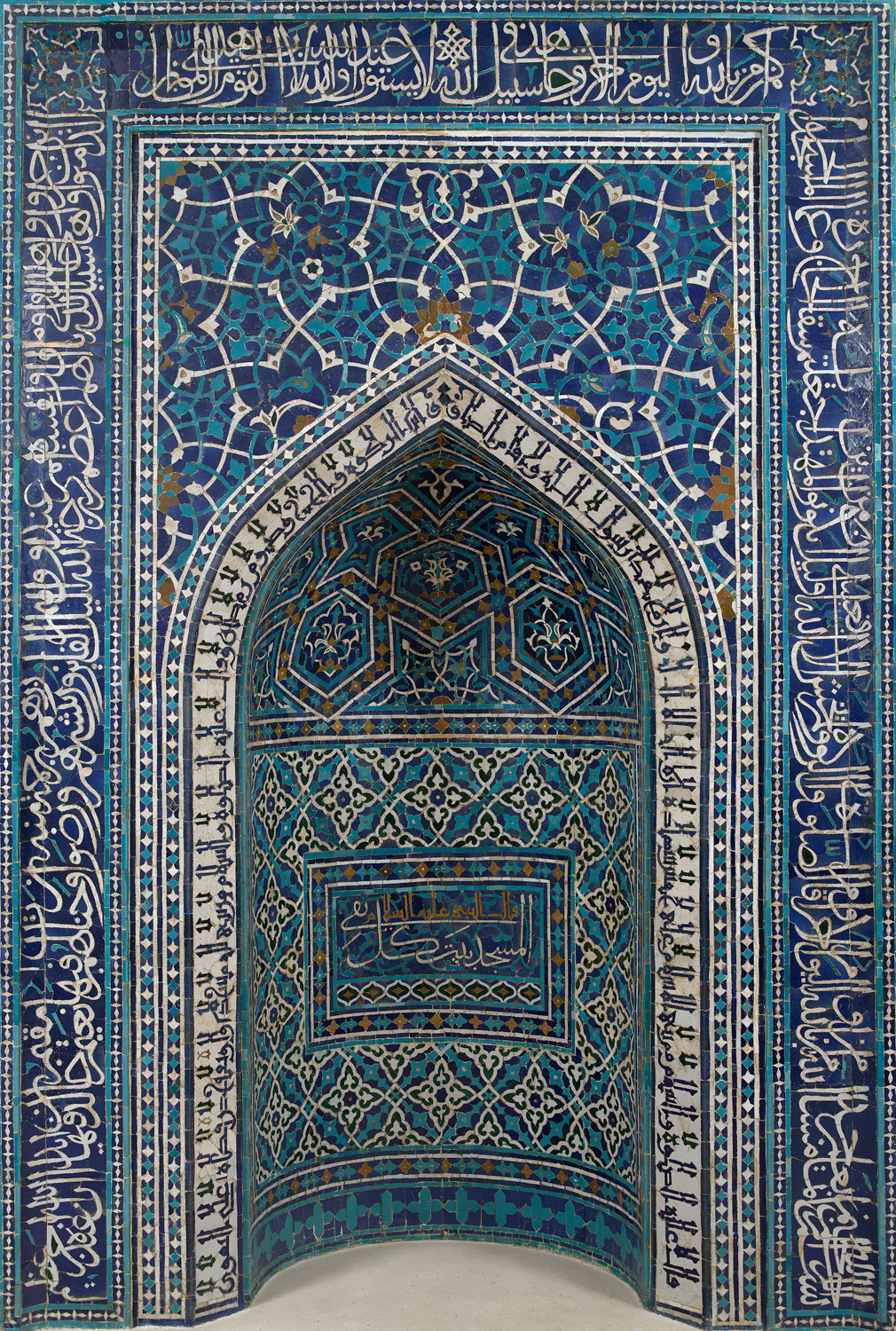

1256–1353

The Ilkhanids, the branch of the Mongol dynasty that takes control of West Asia after putting a definitive end to the Abbasid caliphate (1258), establish rule from the city of Tabriz in northwestern Iran. Following the Ilkhanid sultan Ghazan’s conversion to Islam in 1295, both religious and secular arts flourish. East Asian elements absorbed into the existing Perso-Islamic repertoire create a new artistic vocabulary, one that is emulated from Anatolia to India, profoundly affecting Islamic art. In this regard, the arts of the book, especially illustration, are particularly significant. The widespread use of paper enables the transfer of designs from one medium to another.

-

ca. 1275–1350

Along with their renown in the arts, the Ilkhanids are also great builders. The lavishly decorated Ilkhanid palace at Takht-i Sulaiman (ca. 1275), a site with ancient resonances, is an important example of secular architecture. However, the outstanding Tomb of Uljaitu (built 1307–13; r. 1304–17) in Sultaniyya is the architectural masterpiece of the period. Following their conversion to Islam, the Ilkhanids build numerous mosques and shrines in cities across Iran such as Ardabil, Isfahan, Natanz, Tabriz, Varamin, and Yazd (ca. 1300–1350).

-

ca. 1360–1406

Under the Jalayirids, a Mongol family that establishes rule over Iraq and northwestern Iran during the collapse of Ilkhanid power, art and architecture closely follow the style set by their predecessor. During this period, the art of book illustration is particularly prominent.

-

ca. 1380–1501

After entering Iran in 1380, Timur (Tamerlane, r. 1370–1405), the Turko-Mongolian ruler established in Central Asia, soon controls most of West Asia. Though his vast empire is short-lived, Timur’s descendants continue to rule over Iran and Transoxiana and become leading patrons of Islamic art.

Citation

“Iran, 1000–1400 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=07®ion=wai (October 2001)