Tracing the Rise of Thomas Chippendale, from Hometown Hero to London Lion

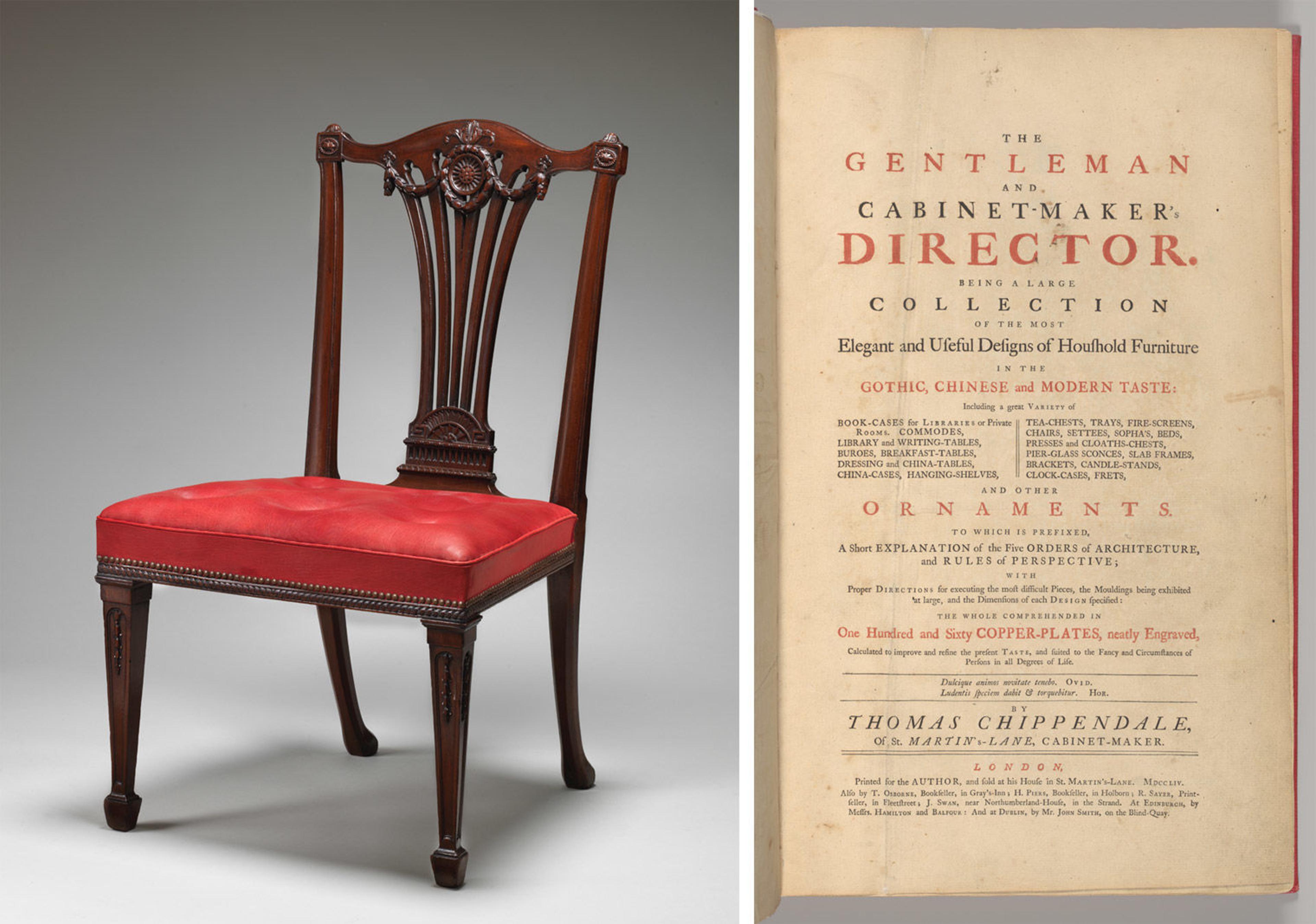

Left: Thomas Chippendale (British, 1718–1779), Side chair from a set of fourteen, ca. 1772. Mahogany, covered in modern red morocco leather, 38 1/4 x 22 x 22 1/2 in. (97.2 x 55.9 x 57.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace and The Annenberg Foundation Gifts, Gift of Irwin Untermyer and Fletcher Fund, by exchange, Bruce Dayton Gift, and funds from various donors, 1996 (1996.426.1–.14). Right: Thomas Chippendale (British, 1718–1779) with engravings by Matthew Darly (British, ca. 1720–1780), Johann Sebastian Müller (German, 1715–1790), Tobias Müller (German, active London, ca. 1752–1778), and Joseph Champion (British, 1709–ca. 1765). The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director. Being a Large Collection of the Most Elegant and Useful Designs of Household Furniture in the Gothic, Chinese and Modern Taste, 1754. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1952 (52.519.94)

Curators often conjure the spirits of their beloved artists by returning to the places that shaped their life and work. In April 2018, I made a pilgrimage to sites connected to the celebrated English designer and furniture maker Thomas Chippendale Sr. (1718–1779) as I prepared the exhibition Chippendale's Director: The Designs and Legacy of a Furniture Maker, on view in galleries 751–752 through January 27, 2019. Thomas Chippendale was a small-town hero with giant ambitions that he not only achieved during his lifetime, but which also served to inspire generations of furniture makers and consumers through his book The Gentleman and Cabinetmaker's Director. I traveled with the Decorative Arts Trust, which generously organized visits to sites linked to the craftsman's life and achievements. For me, returning to Chippendale's origins in Yorkshire and his workshop in London provided an intimate perspective on his evolution as a cabinetmaker, furniture designer, young entrepreneur, and family man.

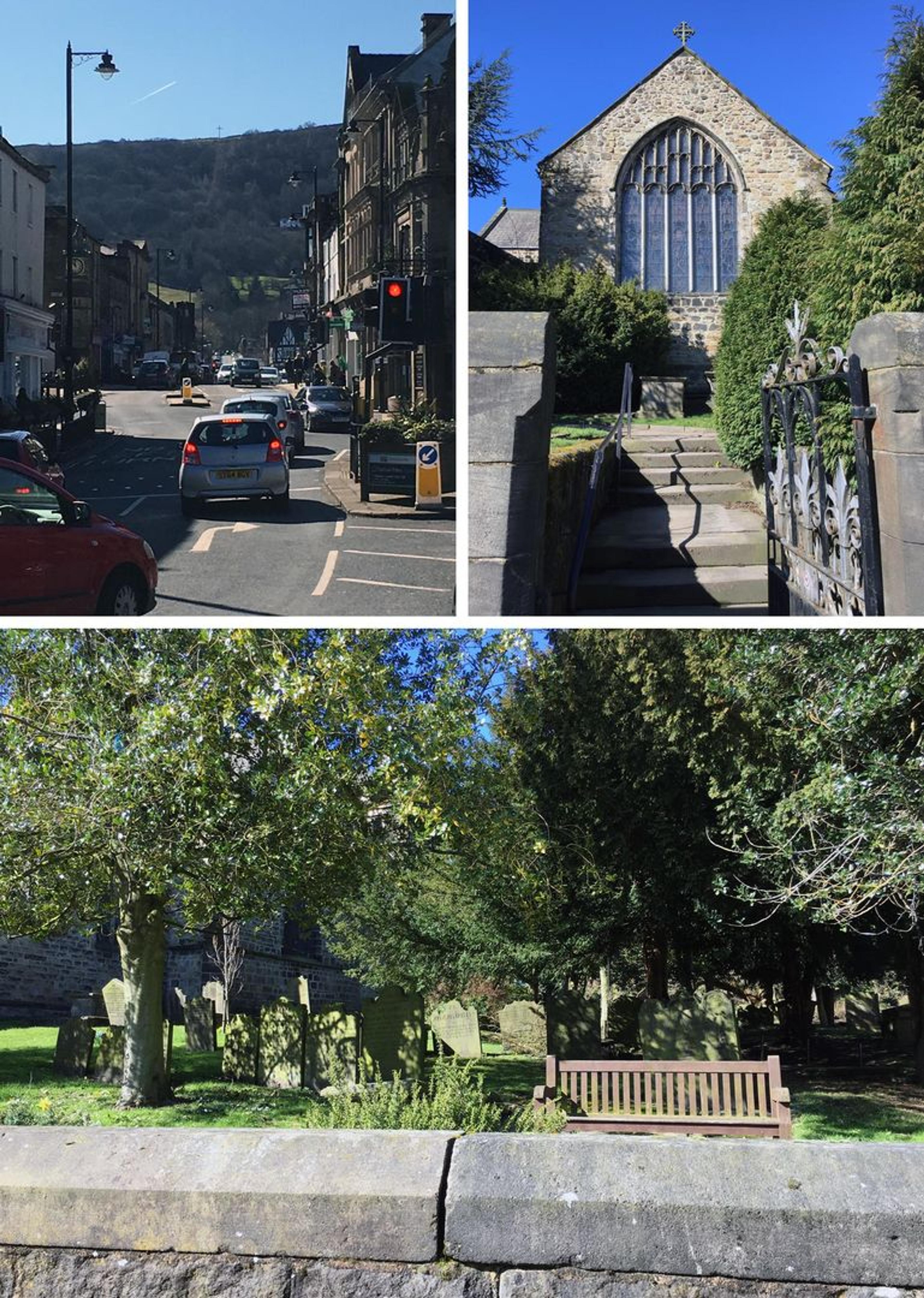

Left: View of modern-day Otley looking towards the Chevin ridgeline. Right: Views of All Saints Parish Church in Otley. Bottom: View of the churchyard of All Saints Paris Church in Otley. Photos by the author

I commenced my journey in the picturesque town of Otley, nestled at the foot of the Chevin ridgeline in the Wharfedale Valley of Yorkshire. John "Chippindale" and his wife, Mary Drake, baptized their son Thomas on June 5, 1718, at the All Saints Parish Church in Otley.[1] According to historic records, John was listed as a joyner (furniture or chair maker) and carpenter, as were other relatives in the Chippindale family—including his grandfather, uncle, cousins, and nephews. Generations of the Chippindale family are laid to rest in the parish churchyard, and some modern-day descendants still maintain the ancient spelling of the Chippindale name.

Left: Statue of Thomas Chippendale Sr. in Otley. Photo by the author. Right: Attributed to John Townsend (1732–1809). Side chair, 1760–70. Newport, Rhode Island. Mahogany, maple, chestnut, white pine, 38 x 20 1/2 x 16 1/2 in. (96.5 x 52.1 x 41.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art,, New York, Purchase, Anthony W. and Lulu C. Wang Gift, 2004 (2004.97). This eighteenth-century, American-made chair from Newport, Rhode Island, exhibits the type of pierced, interlaced back similar to that seen on the statue in Otley.

While there is no known historic portrait of Thomas Chippendale Sr., the town of Otley and a number of Chippendale descendants erected a commemorative statue that is highly popular with tourists. The statue holds a chair back of which there are no surviving examples that have been securely attributed to Chippendale's workshop. However, countless craftsmen, including many American furniture makers, produced the style in the spirit of Chippendale with a fret-sawn design loosely adapted from complex, interlaced rococo chair-back designs featured in Chippendale's Director.

Thomas Chippendale's initiation into the furniture trade remains somewhat of a mystery. His apprenticeship in the trade from ages fourteen to twenty-one is not officially documented, though many scholars believe he may have received his early training from a family member. Emerging from a family of woodworkers would have given Chippendale a tremendous advantage in the trade. After this period, where did Chippendale emerge as an at-will, paid journeyman, from about ages twenty-one to twenty-nine? Furniture historians speculate that Chippendale may have been connected to the master cabinetmaker Richard Wood of York, on account of his subscription to eight copies of the first edition of the Director. York was a thriving commercial entrêpot with plenty of opportunities to engage with aristocratic or mercantile patrons. For a young cabinetmaker from a small parish like Chippendale, it would have been a wise choice to relocate to York.

Top left: A Mapp of the Paris of St. Martins in the Fields (detail), in John Stow, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminister, and the Borough of Southwark, plate 74, 1754–55. Etching and engraving; plate: 14 1/8 x 12 5/8 in. (36 x 32 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1952 (52.519.193[2]). Top right: Thomas Chippendale (British, 1718–1779). China case, from Chippendale Drawings, vol. II, 1753. Black ink, gray wash, 12 1/2 x 8 3/8 in. (31.8 x 21.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.40.2[87]). Bottom: The author on St. Martin's Lane near to where Chippendale's shop would have been. Street numbers and building locations have changed since the 1750s.

Instead, Thomas Chippendale left Yorkshire for London while his younger half-brother, John, succeeded his father in the woodworking business in Otley. For Chippendale, there was considerable risk in leaving a family business that held the possibility of inheriting its capital or networks of clients. Chippendale's bold move illustrated his confidence as a craftsman as well as his entrepreneurial ambition to succeed in one of the most competitive trade communities of the era. The first record of Thomas Chippendale's independent career appears in 1747 in an account of the Earl of Burlington for £6.6s.0 of unspecified work.[2] After marrying Catherine Redshaw on May 19, 1748, at St. George's Chapel in Mayfair, Chippendale settled into a modest home on Conduit Court near Covent Garden in Westminster the following year.[3]

In 1753 Chippendale sought greater visibility by moving to Somerset Court (later renamed Northumberland Court) at the junction of Charing Cross and The Strand. Here, he began preparations for The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director and may have created many of the pen and ink drawings now in The Met collection while working with the engraver and print dealer Matthias Darly (active 1741–1773) on the copper plates for the book illustrations. Chippendale realized his vision to publish the Director with substantial capital invested by James Rannie, a Scottish cabinetmaker and financier, and, after Rannie's death in 1766, Thomas Haig.[4] Chippendale's partnership with Rannie allowed him to expand his business exponentially by way of printing multiple editions of the Director and by moving into a larger space at numbers 59 to 61 on St. Martin's Lane.

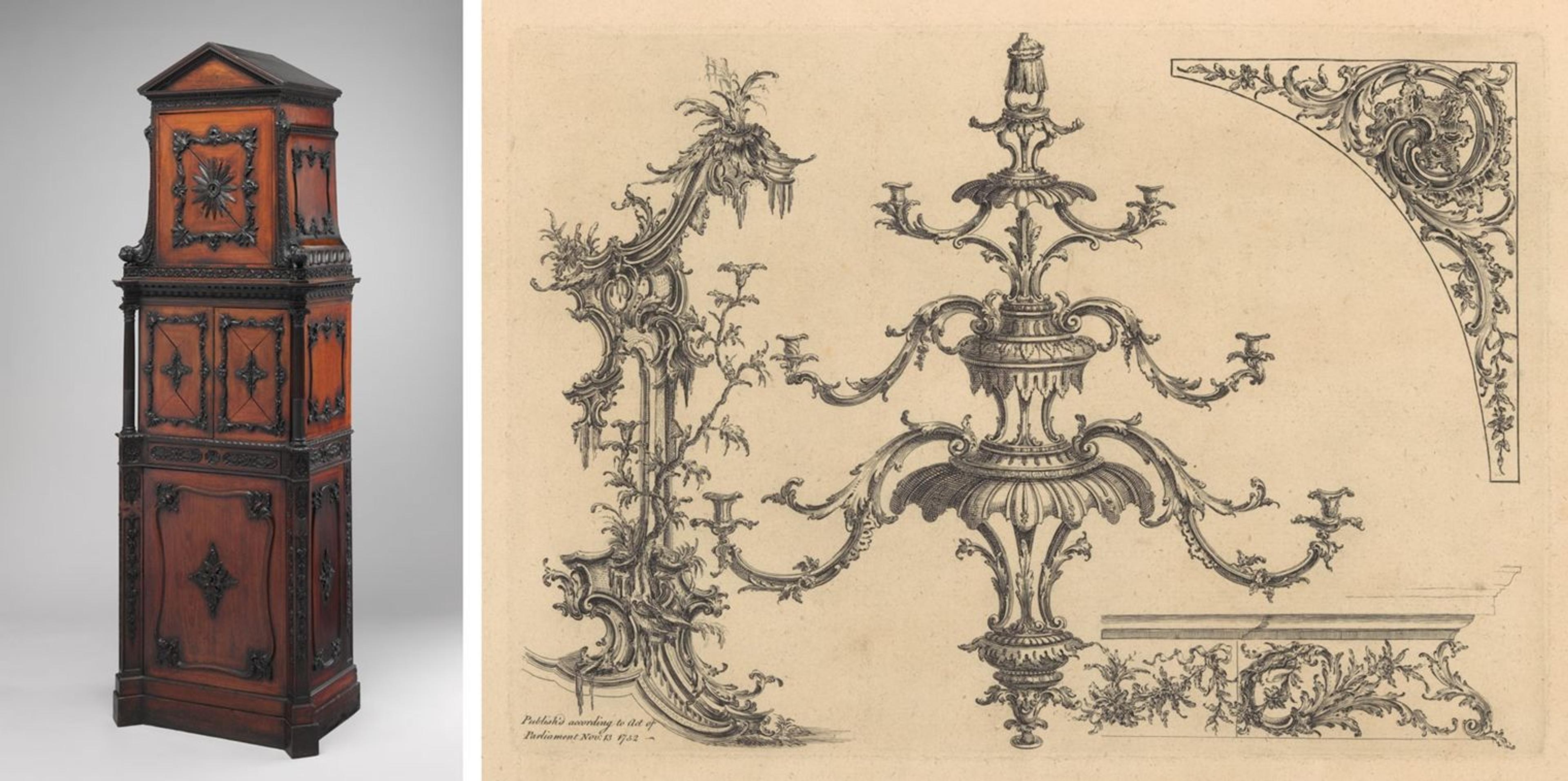

Left: Attributed to William Vile (British, 1715–1767) and John Cobb (British, ca. 1715–1778). Medal cabinet, 1760–61. Mahogany, 79 x 27 x 17 1/4 in. (200.7 x 68.6 x 43.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1964 (64.79). The partnership of William Vile and John Cobb provided constant competition for the neighboring Chippendale workshop by producing exquisitely crafted furniture like this medal cabinet. Right: Designed and published by Matthias Lock (British, ca. 1710–ca. 1765) and Henry Copland (British, ca. 1706–1753). 12 Plates from "A New Book of Ornaments with Twelve Leaves Consisting of Chimneys, Sconces, Tables, Spandle Panels, Spring Clock Cases, Stands, a Chandelier and Girandole, etc.", November 13, 1752. Etching, 14 11/16 x 10 13/16 x 3/16 in. (37.3 x 27.5 x 0.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928 (28.88.7). Scholars credit the carver Matthias Lock for spawning intense interest in the French rococo style in London through a series of prints issued in the 1740s and the widely popular A New Book of Ornaments published with Henry Copland two years before the arrival of Chippendale's Director.

A thirty-five-year-old Chippendale must have brimmed with pride at the sight of his new facility on St. Martin's Lane, which included a residence for his growing family at front and a beehive of workshops for chair and cabinet construction, veneering and inlay, picture-frame making, and upholstering. His son Thomas Jr. eventually expanded into number 62, further extending the family's presence in the district.[5]

St. Martin's Lane buzzed with creativity and competition in the mid-eighteenth century. Chippendale's shop faced Old Slaughter's Coffee House at numbers 74–75, which served as a salon for many craftsmen and patrons in the area. Neighboring craftsmen imposed a constant reminder of the fierce competition for acclaim in the furniture industry with the popular firm of Vile and Cobb residing at number 72 St. Martin's Lane and the preeminent carver Matthias Lock around the corner at Nottingham Court on Castle Street. During my trip, I stood near to where Chippendale's premises had been (street numbers have changed and the building is no longer extant) and imagined the persistent hammering, sawing, and splitting emitting from the busy cabinet and carving workshops, as well as the timely steps of horse-drawn carriages and the grumbling of laborers loading crates with finely gilded, inlaid, and upholstered furniture for Chippendale's patrons. Even the chatter of Chippendale's children as they helped with household chores or were called to perform menial tasks around the workshop crossed my mind.

Left: Newby Hall, Ripon, Yorkshire, England. Between 1772 and 1776, William Weddell worked with Thomas Chippendale on suites of furniture for Newby Hall. Right: Nostell Priory, Nostell, West Yorkshire, England. Between 1766 and 1785, Sir Rowland Winn commissioned Chippendale to create suites of furniture for Nostell Priory and his London townhouse. Photos by the author

More than seven hundred furnishings have been attributed to the Chippendale workshop, many of which were created at St. Martin's Lane, including the set of dining chairs used by merchant Daniel Lascelles at Goldsborough Hall now in The Met collection. Chippendale remained in London until his death in 1779, but his exquisite furniture ventured to glamorous country estates in his native Yorkshire belonging to the Winns of Nostell Priory, William Weddell of Newby Hall, Lord Irwin at Temple Newsam, Edwin Lascelles at Harewood, among many others.

Despite his success, crippling debt related to unpaid accounts led to the eventual dissolution of the workshop by his son in 1803, a fate that befell many craftsmen in the period. Thomas Chippendale's achievements far outweigh his financial failure, though, and Otley in Yorkshire, Charing Cross at the Strand (where Somerset Court once stood), and St. Martin's Lane remain sacred places for the veneration of Chippendale's extraordinary journey.

Notes

[1] Illustrated in Christopher Gilbert, The Life and Work of Thomas Chippendale, vol. I (New York: Macmillan, 1978), fig. 2.

[2] "Private A/C of 3rd Earl of Burlington, 1747–51," Chatsworth muniments; quoted in Gilbert, 128.

[3] Chippendale and Catherine Redshaw had nine children: five boys, including Thomas Chippendale Jr., and four girls. In 1772, Catherine died and Chippendale remarried in 1777 to Elizabeth Davis, with whom he would have three more children.

[4] Chippendale remained in partnership with Rannie until Rannie's death in 1766. Rannie selected Thomas Haig, his bookkeeper, to take over operations after his death.

[5] Thomas Chippendale Jr. (1749–1822) succeeded his father in the furniture-making business, and took a more active role in the 1770s. Thomas Jr. was confronted with considerable debt that eventually forced him to dissolve the shop.

Related Content

Chippendale's Director: The Designs and Legacy of a Furniture Maker is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 27, 2019.

Take a walkthrough of the exhibition galleries and view a selection of objects featured in the exhibition.

Explore the life of Thomas Chippendale and his creation of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director in a Timeline of Art History essay by exhibition co-curator Femke Speelberg.

Published in concert with the exhibition, a Bulletin on Chippendale's Director by Morrison H. Heckscher, curator emeritus of the American Wing, is available for purchase at The Met Store.

Alyce Englund

Alyce Perry Englund, Assistant Curator of American Decorative Arts, joined the American Wing in June 2015, and oversees the seventeenth- to early nineteenth-century furniture collections. Previously she worked at the Wadsworth Atheneum; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and Historic New England (SPNEA). She received her MA from the Winterthur Program in American material culture, a BA in art history from the University of Vermont, and is an alumna of The Attingham Study Programme. She has organized exhibitions on topics such as decorative arts from Connecticut, poetry and art, and the Civil War, and has published scholarship on japanned furniture, Connecticut's Federal Era cabinetmakers, and folk art. At The Met, she curated Simple Gifts: Shaker at the Met (2016–17) and co-curated Chippendale's Director: The Designs and Legacy of a Furniture Maker (2018–19).