Celebrating Pride Month with The Met Collection

Clockwise from top left: Portraits of Oscar Wilde, Walt Whitman, David Wojnarowicz, and Jane Heap

"Revolution only needs good dreamers who remember their dreams."

—Tennessee Williams, Camino Real

Although the first Pride events in 1970 brought queer activists and allies together to march as a potent symbol of visibility and resistance one year after the Stonewall Uprising, the quest for equality and the acceptance of sexual minorities began about one hundred years earlier in Europe. Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German activist considered to be the first openly homosexual man, began a difficult and public campaign in the 1860s to reverse the criminalization of homosexual acts included in the Prussian penal code. The focus to his argument: Ulrichs considered his condition of same-sex attraction to be inborn, and therefore deserving of respect and not persecution. Although Ulrichs's campaign failed to overturn the legislation, it forged an important connection between homosexuals and the medical community, which, through the work of sexologists such as Magnus Hirschfeld and Alfred Kinsey, brought much-needed insights into the natural state of homosexuality, a fundamental principle of the argument for equal rights.

To commemorate Pride Month and the more than 150 years of progressive action that has informed the continued activism needed in today's political climate, follow this digital itinerary of works in The Met collection by, or depicting, artists from the LGBT community. These paintings and photographs showcase a breadth of diverse voices at different moments of progress and regress—from an American swept up in the queer utopia of Berlin before the outbreak of World War I, to those struck down in the prime of their careers by the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, and the much-beloved painter of a recent presidential portrait.

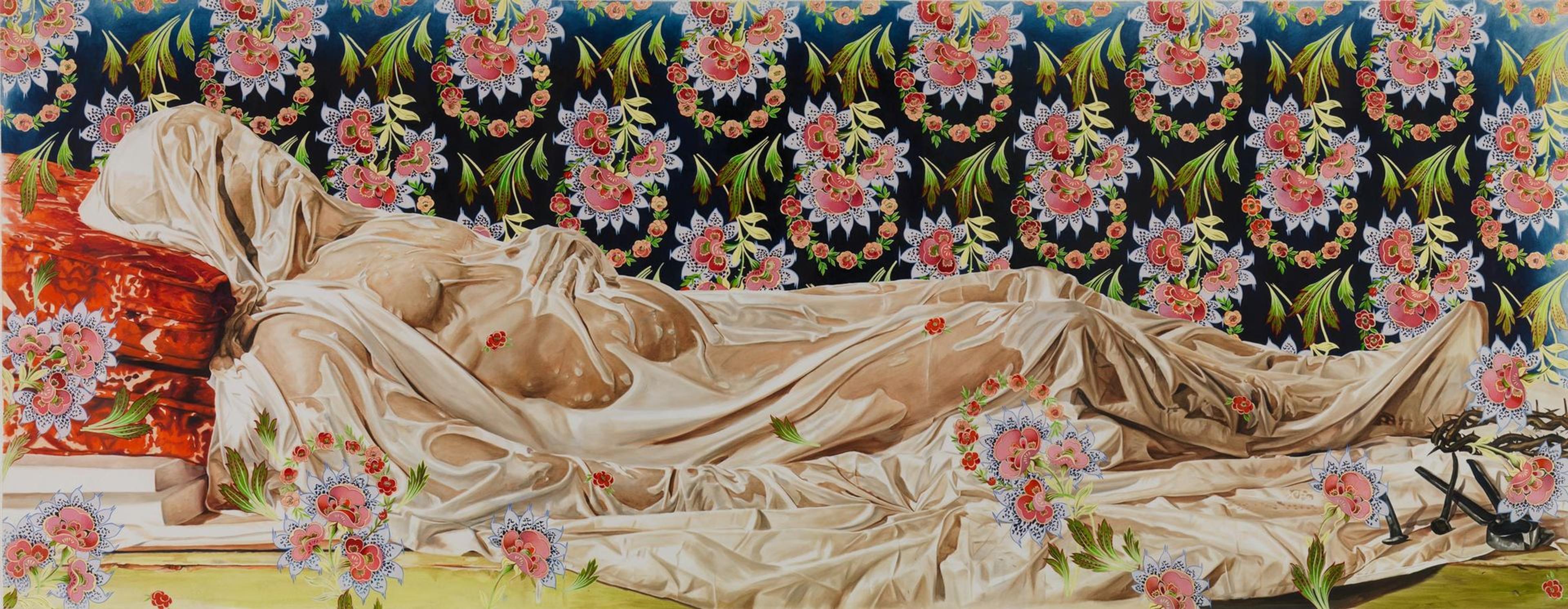

Oscar Wilde, Walt Whitman, Jean Cocteau

From left: Napoleon Sarony (American [born Canada], 1821–1896). Oscar Wilde, 1882. Albumen silver print, 30.5 x 18.4 cm (12 x 7 1/4 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Gift, 2005 (2005.100.120). John White Alexander (American, 1856–1915). Walt Whitman, 1889. Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Jeremiah Milbank, 1891 (91.18). George Platt Lynes (American, 1907–1955). Jean Cocteau, ca. 1937. Gelatin silver print, 34.1 x 26.9 cm. (13 7/16 x 10 9/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Russell Lynes, 1983 (1983.1160.10). © Estate of George Platt Lynes

Three titans of the gay literary canon all have portraits in the Museum's collection. Walt Whitman, the father of free-verse poetry, was an indefatigable writer best known for Leaves of Grass, a tome of humanist poetry denounced as obscene in 1855 for its overt sexuality and references to male love. (The Met also has a portrait of one of Whitman's lovers, Bill Duckett, taken by Thomas Eakins.) Whitman's message was one of collectivism and progress at a time when the country was deeply divided and devastated by civil war; he even composed searing war poetry while serving as a volunteer nurse at a military hospital.

In contrast to the earthiness of Whitman's writing, Oscar Wilde's work in late nineteenth-century England is a feast of linguistic jewel tones and intoxicating perfume. Wilde earned great renown equally for his work as a playwright and novelist as for his popular profile in London society. Because of this célébrité, Wilde made front-page news during the infamous obscenity trial brought upon him in 1892 by the father of his tempestuous lover Lord Alfred Douglas (frequently referred to as "Bosie"), in which Wilde was found guilty of indecency and charged with two years' imprisonment in Reading Gaol. During the final months of his incarceration, Wilde wrote a lengthy letter to Douglas—later published after the writer's death as De Profundis—in which he directs a series of devastating barbs at Douglas and profiles his spiritual development while in prison, ultimately condemning shallowness—an attribute he praised earlier in his life—as "the supreme vice."

Jean Cocteau was a wunderkind of interwar Paris, where he socialized and collaborated with the most prominent members of the cultural avant-garde, including the artists Pablo Picasso, Amadeo Modigliani, and Léon Bakst; writers Marcel Proust, André Gide, and Maurice Barrès; composers Igor Stravinsky, Maurice Ravel, and Erik Satie; and Ballets Russes impresario Sergei Diaghilev. Cocteau was very open about his sexuality, and lived famously as a couple with the actor Jean Marais, whom he cast as the Beast in his 1946 film La Belle et la Bête. Cocteau's 1928 book Le Livre Blanc (The White Paper) was a plea for homosexual acceptance so impassioned that it reads as a credo—with a condemnation of society so strong that he submitted the manuscript for publication anonymously:

I have always loved the stronger sex and believe that it can legitimately be called the fair sex. My misfortunes are due to a society which condemns anything out of the ordinary as a crime and forces us to reform our natural inclinations.[1]

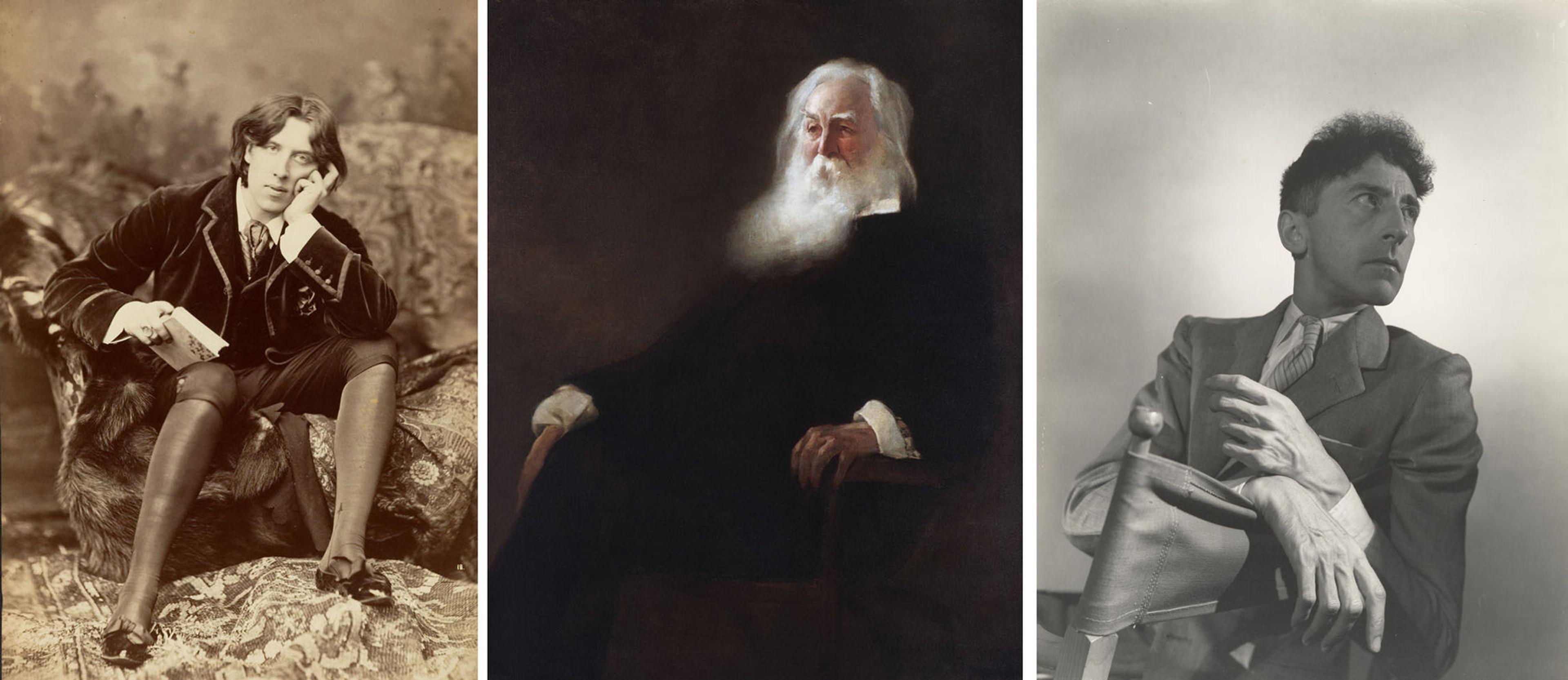

Kehinde Wiley

Kehinde Wiley (American, born 1977). The Veiled Christ (study), 2008. Oil wash on paper, 56 11/16 x 145 1/4 in. (144 x 369 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Francis Lathrop Fund, 2008 (2009.14). © Kehinde Wiley

Shot into the pop-culture stratosphere of fame earlier this year thanks to his official portrait of former president Barack Obama, Kehinde Wiley has already been a staple of the contemporary art world for more than a decade. His mid-career retrospective, Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic, was critically acclaimed in each of its three venues, and his paintings have become instantly recognizable. His canvasses are larger than life, and position realist portraits of young African Americans in contemporary clothing against a backdrop of elegant, energetically colored decorative designs that calls to mind both the Old Masters and the dandy aesthetics of a Wildean drawing room.

In his study for The Veiled Christ, Wiley references Renaissance and Baroque depictions of Christ before his Entombment—most specifically a Giuseppe Sanmartino sculpture (1753) in the Cappella Sansevero in Naples, as well as Hans Holbein the Younger's The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1520–22)—but imbues the overall composition with his signature decorative elements. Where Holbein confronts the viewer with a Christ of deathly pallor, Wiley wraps his figure in a winding sheet of elegant silk, on which fresh wildflowers are strewn. In direct contrast to Holbein's scene of existential dread, Wiley's is a death softened by a recumbent pose (Christ's head is supported by plush cushions, as in the Sanmartino), saturated color, and decadent fragrance.

Berenice Abbott

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991). Jane Heap, ca. 1928. Gelatin silver print, 24.1 x 18.7 cm. (9 1/2 x 7 3/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Laura May Isaacson, 1976 (1976.601.2). © Berenice Abbott / Commerce Graphics Ltd. Inc.

Berenice Abbott defied her poor upbringings in rural Ohio to become the toast of 1920s Paris, where she gained great notoriety as a celebrity photographer thanks to her pictures of literary giants such as Jean Cocteau, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Djuna Barnes. After a brief stint living in Greenwich Village, Abbott left for Paris, where she worked for several years as a darkroom assistant to the surrealist Man Ray. Her time in Ray's studio proved invaluable, as it was there she discovered her love for photography as a medium (she had initially shown interest in being a sculptor) and developed her sympathetic gaze and laser-focused realism. After returning to New York in 1929 and changing her focus from portraiture to documentary urban photography, Abbott would go on to spend more than thirty years of her life in a relationship with the journalist Elizabeth McCausland.

Among The Met's rich holdings of Abbott's work is her portrait of Jane Heap, the celebrated literary figure and co-founder—with her lover and longtime business partner Margaret Anderson—of The Little Review, an avant-garde journal that counted among its contributors Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and William Carlos Williams, as well as a roster of then-unknowns like Hart Crane, Ernest Hemingway, and Gertrude Stein. Heap and Anderson leapt at the chance to publish James Joyce's Ulysses as a serial in The Little Review, a decision that ultimately led to the police raiding their Greenwich Village offices, and their each being fined fifty dollars under the charge of publishing "indecent matter."

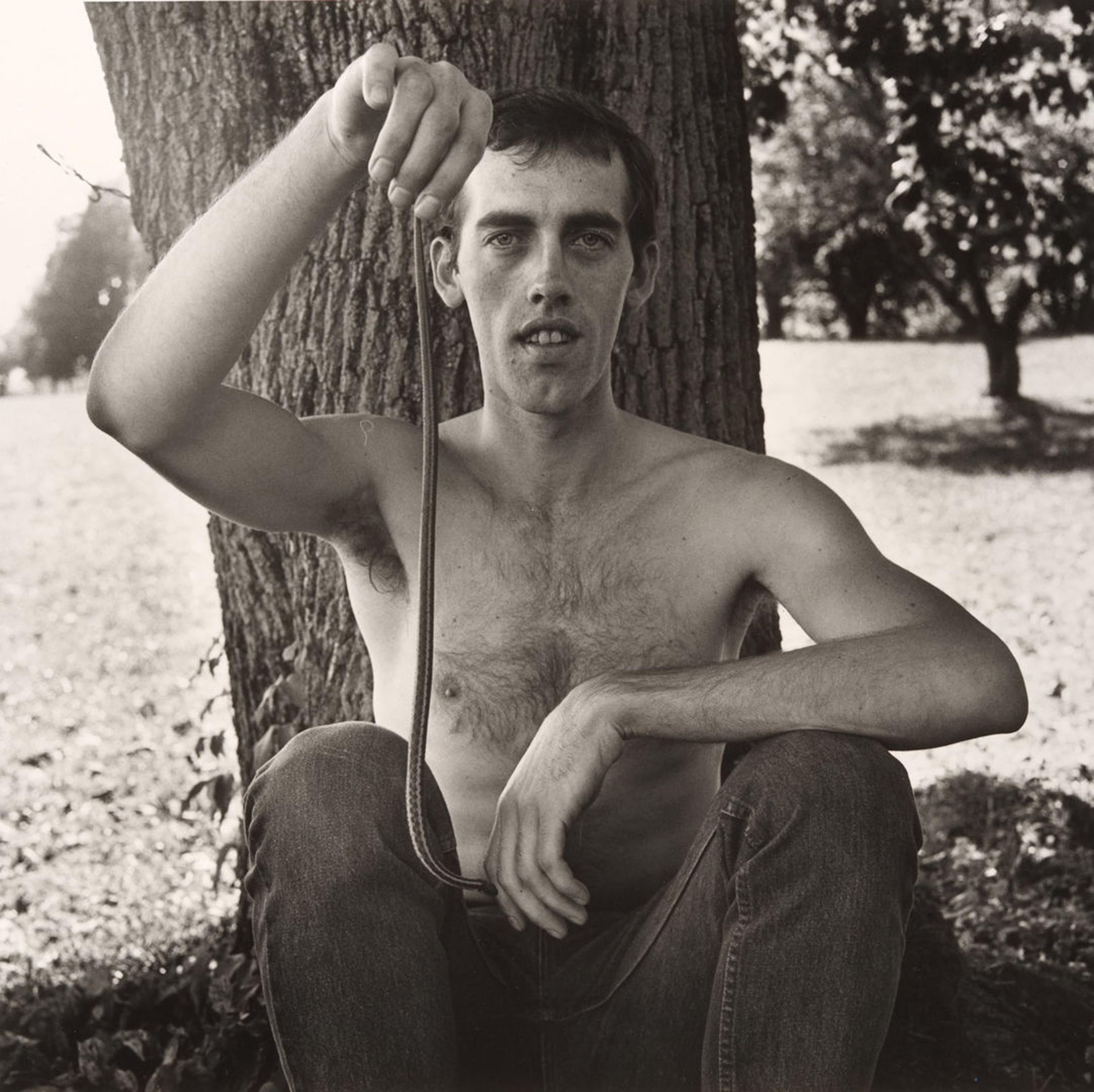

Peter Hujar

Peter Hujar (American, 1934–1987). David Wojnarowicz with a Snake, 1981. Gelatin silver print, 37.5 x 37.1 cm (14 3/4 x 14 5/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2006 (2006.287). © The Peter Hujar Archive, L.L.C.

Peter Hujar was a fixture of Downtown New York in the 1970s and '80s, where he chronicled the city's gritty nightlife and its notorious celebrities, including transgender actress and Warhol Factory star Candy Darling, drag queen and actress Divine, openly bisexual writer Susan Sontag, and fellow queer artist David Wojnarowicz, a mentee of Hujar's with whom he enjoyed a yearslong relationship. Although a contemporary of Diane Arbus and an influence on Robert Mapplethorpe, Hujar never enjoyed the success of those artists, most likely due to Hujar's refusal to promote his work. (Portraits in Life and Death was the only book he published in his lifetime.) Seeking out subjects who, as he noted, "cling to the freedom to be themselves," Hujar focused on the natural shamelessness of those he photographed, which placed him at odds with an artist like Mapplethorpe, whose work Hujar found too glossy, indulgent, and inauthentic compared to what his lens caught and communicated to the viewer with a pulsating rawness.

Hujar shot David Wojnarowicz with Snake in 1981, while the two were lovers. Captured in a year also marked by the first known cases of HIV, the simple pastoral scene carries a sense of innocence. Lacking the chiaroscuro and dramatic lighting present in other portraits Hujar took of Wojnarowicz, this picture shows as its subject a seemingly uncomplicated young man at home in nature and among its creatures. In Wojnarowicz, Hujar found a kindred spirit, another artist with a troubled childhood who used his voice to offer authentic critiques of the world around him. Although born twenty years apart, both men would succumb to AIDS within just a few years of each other: Hujar in 1987, and Wojnarowicz in 1992.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres

Felix Gonzalez-Torres (American [born Cuba], 1957–1996). [No Title], 1985. Instant black-and-white print, 7.2 x 6.9 cm (2 13/16 x 2 11/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 1997 (1996.575). © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

The work of Cuban-born artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres confronted a number of contemporary social and political causes, both from his perspective as an openly gay man and through his adoption of Bertolt Brecht’s theory of "Epic Theater," which sought to transform creative expression into points of action that actively engaged the viewer as receiver. A prominent voice during the AIDS crisis—the disease would claim Gonzalez-Torres in 1996—his works defiantly critiqued society, government, and individuals, and ranged in media as varied as photography and cellophane-wrapped candy.

In an example of the latter medium, Untitled (Ross in L.A.), Gonzalez-Torres called for an installation of exactly 175 pounds of candy—the weight of his lover at the time he was diagnosed with AIDS—against a bare gallery wall, from which visitors are welcome to take a piece of candy with them. Thus the assemblage becomes smaller over time, mirroring that of an AIDS victim's decaying body. In [No Title] from The Met collection—an outlier in Gonzales-Torres's oeuvre—the openness of the scene can be read as a reference to the sense of wandering the artist felt after leaving his native Cuba, or the metaphysical longing of an urbanite for expansive surroundings.

Frida Kahlo

Nickolas Muray (American [born Hungary], 1892–1965). Frida Kahlo, 1939. Carbro print, 42.7 x 32.2 cm. (16 13/16 x 12 11/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Warner Communications Inc. Purchase Fund, 1978 (1978.608). © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

One of Mexico's most prominent artists, Frida Kahlo rebelled against many of the social norms of her time: she was a female artist in a male-dominated field; a sexually fluid character who counted both men and women as lovers; and a staunch Communist activist at a time of great hostility to such leftist views. The significance of Kahlo's queerness, however, is reflected in more than just her lesbian relationships. In addition to her fearless depiction of homoerotic scenes in her paintings, she was also an expert cross-dresser who used the art of drag not only to project power but also a great sense of transgressive independence in line with her politics. (Kahlo had an affair with Leon Trotsky during her marriage to Diego Rivera, and oftentimes lied about her date of birth so that it would align with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.)

Kahlo began painting after suffering a vehicular accident in 1925 that left her with numerous spinal and pelvic fractures, injuries that would come to plague her throughout the rest of her life. Autobiographical in nature, her work embodies her pain and struggle, but on a purely artistic level there is great energy and vitality to her bold color palette and quasi-surrealist scenes. She gained international notoriety, which culminated in her first solo exhibition in Mexico, held at the Galeria de Arte Contemporaneo in 1953, one year before her death. Bedridden at the time of the opening, Kahlo arrived by ambulance and spent the evening celebrating the occasion while situated in her four-poster bed, which had been transported and installed in the gallery to accommodate her attendance.

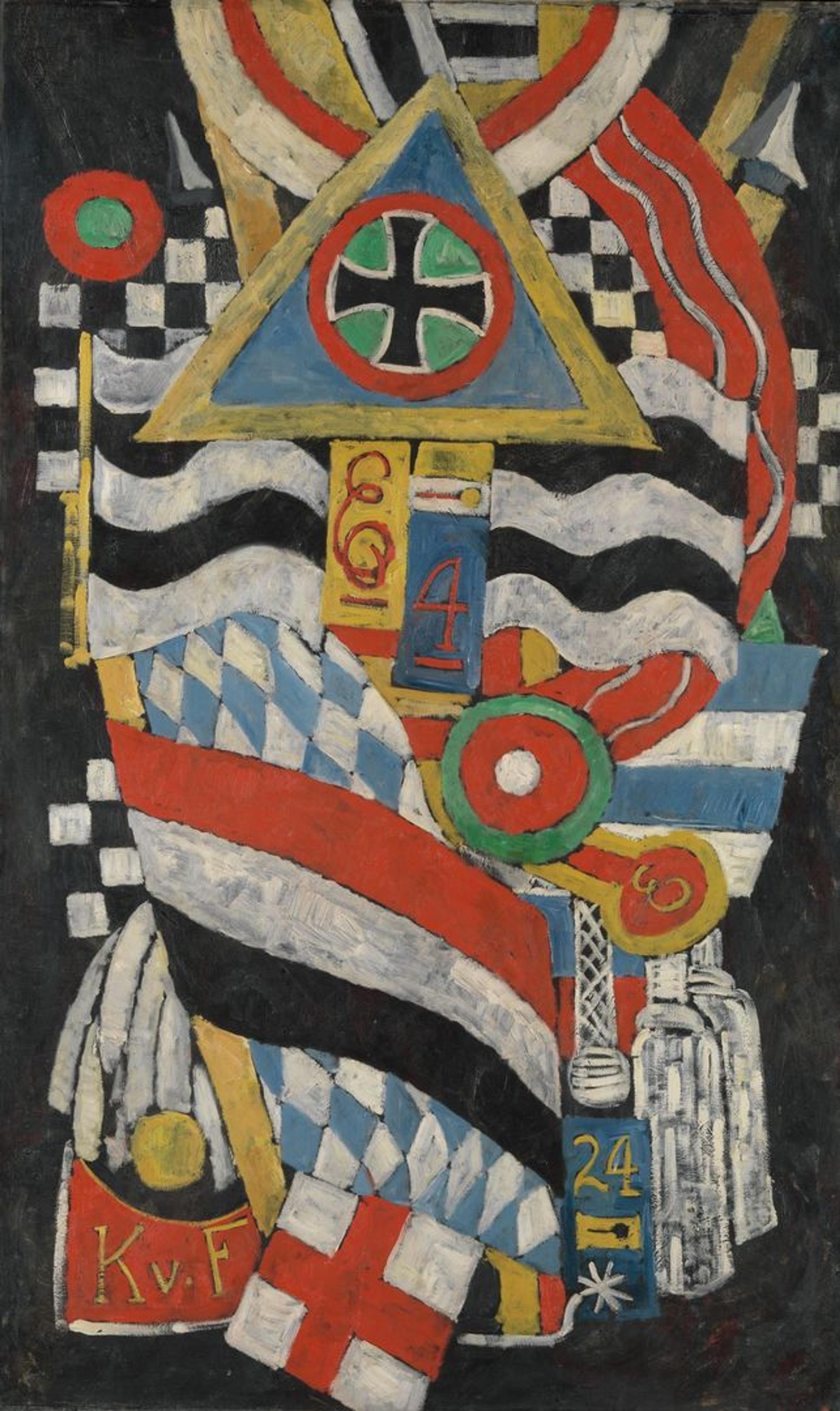

Marsden Hartley

Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Portrait of a German Officer, 1914. Oil on canvas, 68 1/4 x 41 3/8 in. (173.4 x 105.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.42)

In 1912, Hartley made his maiden voyage to Europe—first to Paris, then to Berlin, where he became enthralled with the energy and pageantry of Wilhelmine Germany and its military parades of strapping young soldiers. There he met and fell in love with Karl von Freyburg, a Prussian soldier who was to die in the first year of World War I. After von Freyburg's death, Hartley's view of the war turned to mournful loss, exemplified by a number of paintings—the War Motif series—in which the artist memorialized von Freyburg using a coded language comprising otherwise unassuming military symbols and patterns.

The greatest of these is arguably Portrait of a German Officer, a life-size memorial to von Freyburg painted in Hartley's signature mix of Synthetic Cubism and German Expressionism. Found within the painting are the officer's initials, "KvF"; "4," the military regiment in which he served; "24," the age at which he died; an Iron Cross, which he had been honored with shortly before his death; and a chessboard, in reference to von Freyburg's favorite game. Hartley returned to the United States in 1915 due to the escalating horrors of the war, eventually returning to his home state of Maine. As the climate toward sexual minorities in the United States was more conservative than that of Berlin, Hartley spent the rest of his career observing and painting—most likely only from a distance—the fishermen, lifeguards, and workers of his coastal town, where he remained until his death in 1943.

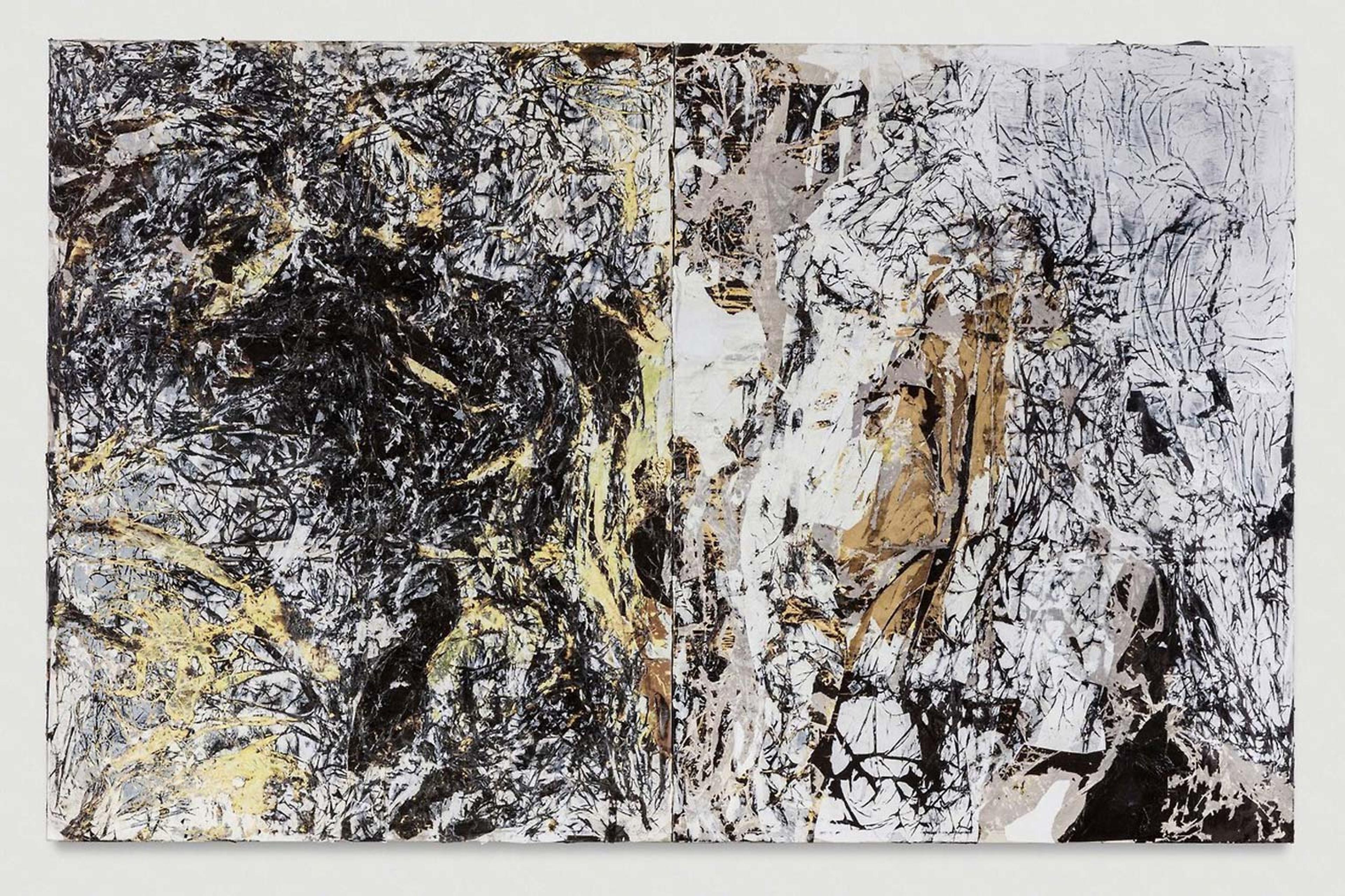

Mark Bradford

Mark Bradford (American, born 1961). Duck Walk, 2016. Mixed media on canvas, 9 1/4 x 14 ft. 1/2 in. (275 x 428 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anonymous Gift, 2017 (2017.291a, b). © Mark Bradford, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Mark Bradford addresses themes of race, gender, and class through large-scale abstract works composed of layer upon layer of salvaged paper, string, and glue. Bradford's work first came to prominence in the Studio Museum of Harlem's 2001 groundbreaking exhibition Freestyle, and he has since seen solo shows produced at the Whitney Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The artist selected to represent the United States at the 2017 Venice Biennale, Bradford's exhibition, Tomorrow Is Another Day, explored the rise of authoritarianism in the United States, police brutality, and the country's centuries-long history of slavery and racial oppression.

A more light-hearted work, his Duck Walk (2016) makes reference to a dance move popular in "voguing"—an essential element of the African American ballroom culture in Harlem that rose to prominence outside of New York City after the release of the 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning. The muted color palette and jagged contours of the work refer to Abstract Expressionism, and particularly the paintings of Clyfford Still, a great influence on Bradford's practice. (Duck Walk was, in fact, created specifically for a 2016 exhibition at the Albright-Knox Museum that put Bradford's work in conversation with twenty of Still's paintings.)

Note

[1] Jean Cocteau, Le Livre Blanc (London: Peter Owen Publishers, 2013), 21.

Related Content

The Artist Project: "Kehinde Wiley on John Singer Sargent"; "Mark Bradford on Clyfford Still"

Read essays related to these artists on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Art and Photography: The 1980s"; "Abstract Expressionism"; "Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and His Circle"

Michael Cirigliano

Michael Cirigliano II is the managing editor in the Digital Department.