A Bearded Man, a Water Bird, and a Divine Monkey: Recent Gifts of Mesoamerican Art

«Stone and ceramic sculptors in ancient Mesoamerica mastered representations of their subjects both in the round and in low relief. Such artists were held in high regard by their communities; in ancient Maya civilization, for example, we know that they were important enough to sign their masterworks. The works of three new sculptors from ancient Mexico—though their names have gone unrecorded—are now a part of The Met collection and are on display in gallery 358. All three artists exhibit a high degree of naturalism in some respects, but in each case they selectively depart from a faithful rendering of reality. How they did so speaks volumes about the mythological characters they featured in these works from three distinct moments in Mesoamerican history.»

For peoples of the Olmec civilization (ca. 1200–400 B.C.) in the Gulf Coast of Mexico, greenstone, especially jadeite, was perhaps the most highly valued material (a topic that will be explored in great depth in the upcoming exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas). Other greenstones, such as serpentine, were equally valuable and often employed in massive quantities as dedicatory offerings for ritual spaces. At the site of La Venta, for example, tiled mosaic pavements were buried deep within monumental buildings, stacked on top of each other in verdant opulence. The colossal sculpture at La Venta also included large "altars" of volcanic stone that may have functioned as thrones for political leaders. The throne known as Altar 4 features a male figure seated cross-legged, leaning forward out of the mouth of a cave, grasping a rope. The act of sitting or kneeling while leaning forward is a trope in Olmec-period sculpture that seems intimately tied with the civilization's rulers, though the exact systems of governance remain opaque.

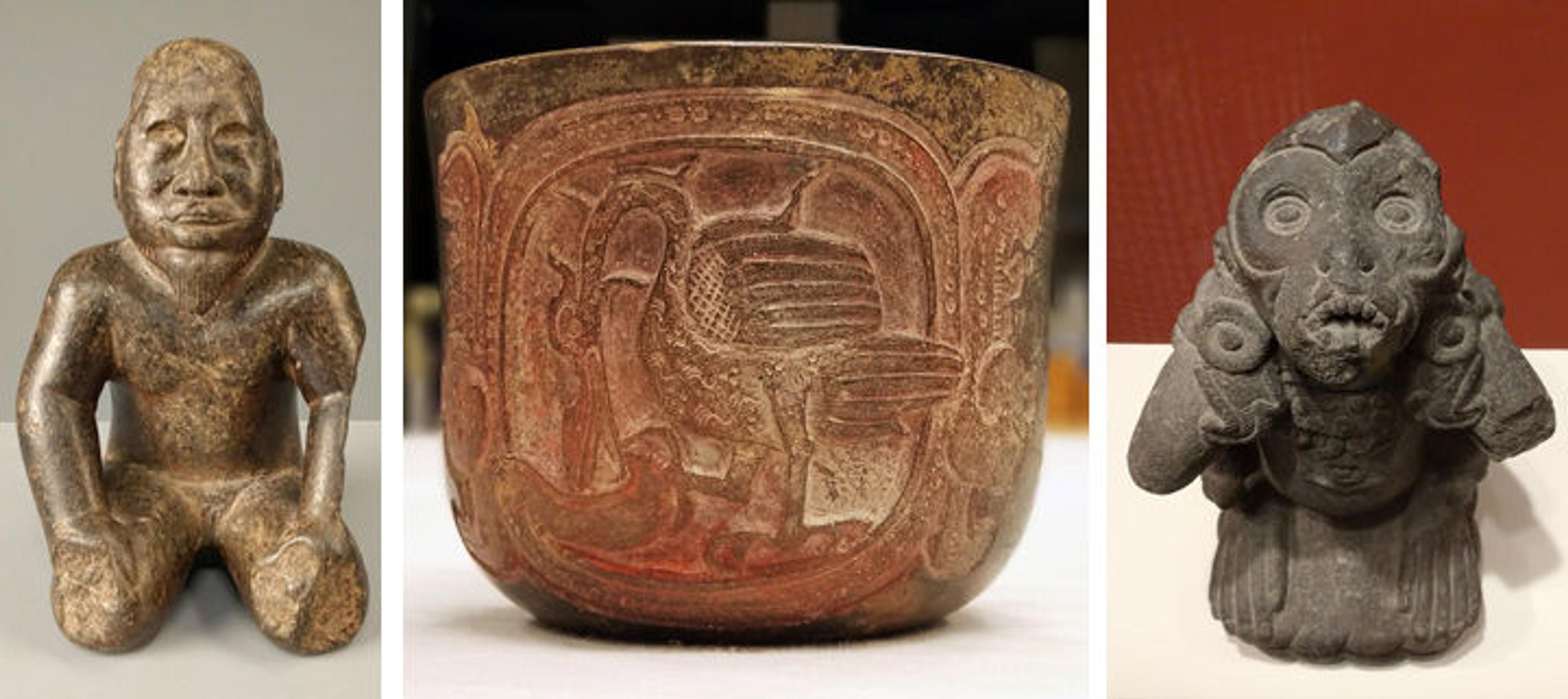

Fig. 1. Kneeling bearded figure, 900–400 B.C. Mexico, Puebla. Olmec. Serpentine, H. 29.3 x W. 18 cm x D. 16 cm (H. 11 9/16 x W. 7 1/16 x D. 6 5/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Hope Collection, 2017 (2017.443)

Depicting a kneeling figure, this intimately scaled serpentine sculpture is notable for its harmonious proportions, subtle musculature, and dynamic pose (fig. 1). This stately portrait of an Olmec-period ruler was reportedly found in Puebla, away from the Gulf Coast homeland, just as other Olmec-style art in ceramic. The image is somewhat individualized. Incised details indicate a stylized coiffure and a beard along the jaw that comes to a point. The head, perhaps exhibiting cranial modification that was found among Olmec societies, features empty eye sockets, perhaps once inlaid with shell or stone. The hands and feet were broken off in antiquity and the left arm has also suffered losses.

The sculpture belongs to an important class of works depicting kneeling males in various states of transformation into, or impersonation of, powerful feline deities. A similar work in the Cleveland Museum of Art's collection suffered more damage in antiquity, while smaller examples in the Princeton University Art Museum and the Dumbarton Oaks Museum are better preserved (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Left to right: Kneeling figure, ca. 1200–600 B.C. Mexico, Guerrero. Olmec. Stone, 26.3 x 20 x 21.3 cm (10 5/16 x 7 13/16 x 8 3/8 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, The Norweb Collection, 1951.179. Kneeling lord with incised toad on his head, 900–500 B.C. Mexico, Veracruz. Olmec style. Stone with red pigment, H 17.6 x W. 10.8 x D. 10.1 cm (6 15/16 x 4 1/4 x 4 in.). Princeton University Art Museum, Museum purchase, Gift of Mrs. Gerard B. Lambert by exchange, y1976–21. Kneeling transformation figure, 900–300 B.C. Mexico. Olmec. Serpentine with red pigment, 19 x 9.7 x 10.6 cm (7.5 x 3.8 x 4.2 in.). Dumbarton Oaks Pre-Columbian Collection, PC.B.603

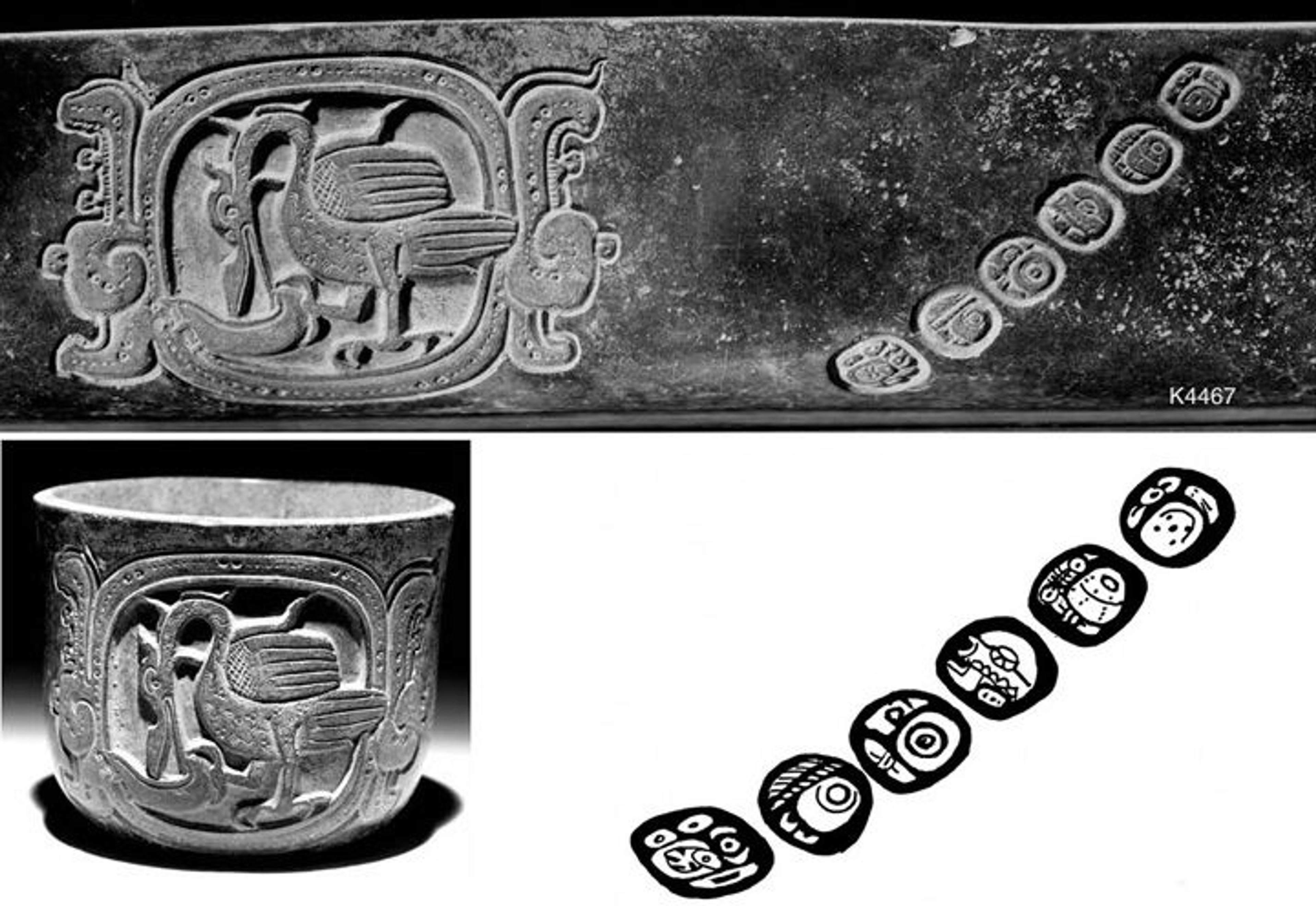

Maya ceramics were one of the principal media for artistic expression in the first millennium A.D. One Maya artist of the Late Classic Period (ca. A.D. 650–900) built this hemispherical ceramic drinking cup out of orange-brown clay from the northern Yucatan Peninsula (fig. 3). Before firing, the surface was decorated with a cartouche with a bird in its interior on one side and a hieroglyphic text on the other. The design was created by gouging and incising the surface of the clay and applying a dark brown mineral slip. Red pigment was later applied to the fired surface. The resulting contrast highlights the image of a water bird—perhaps a cormorant or heron—grasping an object, and a diagonal hieroglyphic text composed of six rounded glyph blocks (fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Vessel with water bird and hieroglyphic text, 7th–9th century. Mexico. Maya. Ceramic, H. 11.4 cm (4 1/2 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Justin Kerr and Dicey Taylor, 2017 (2017.396)

This gift from the collection of a renowned photographer of Maya vessels, Justin Kerr, represents an important style known as Chocholá, named after a small town in the northern Yucatan Peninsula, in the area from which many of these vessels reportedly came. The corpus of Chocholá vessels is limited to perhaps fewer than 50, and this depiction of a water bird is a unique image among known vessels. Evoking the texture, color, and feeling of wooden vessels, it is one of the finest vessels created in this iconic style, which would have been prevalent at the time in Maya royal courts. The vessel was first exhibited in New York in 1971 in the landmark exhibition The Maya Scribe and His World at the Grolier Club. An interesting detail is that the diagonal column of hieroglyphs would have been vertical only as the cup was being used, a perspective most visible to a viewer next to the drinker (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Rollout photo by Justin Kerr (K4467)

Another seated figure, though a decidedly non-human subject, joins The Met's strong group of Aztec (Mexica) sculpture from late Postclassic Mexico (ca. A.D. 1250–1521). Aztec sculptors were widely recognized as possessing great skill, and a large collection was acquired by The Met in 1900 from diplomat Luigi Petich. Another landmark standard bearer in a provincial Aztec style was purchased in 1962 as the Museum geared up to receive the major group of works from Nelson Rockefeller's Museum of Primitive Art. The Michael C. Rockefeller Collection added stone sculptures, but regalia in gold and obsidian as well, to round out the full story of Aztec creativity currently on view. The Met's major collaborative exhibition Mexico: Splendors of Thirty Centuries shined the spotlight on the impressive Aztec collections in Mexico's national museums.

Fig. 5. Spider monkey with wind god regalia, 13th–16th century. Mexico. Aztec. Stone, H. 39.5 cm (15 9/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Brian and Florence Mahony, 2017 (2017.393)

A rare and exciting addition to The Met collection now allows a new dimension of Aztec art and religion to be featured. In this sculpture, a spider monkey (Ateles geofroyi) peers up at visitors to gallery 358 as if imploring them to look closely. It is seated on its haunches, elbows raised forward, and forearms and hands reaching back over the shoulders to grasp its own prehensile tail (fig. 5). The monkey's head is tilted back and his open mouth reveals its sharp teeth. In the wild, this expression is common in aggressive behavior, though most people would have merely seen them racing through the trees in acrobatics. They were perhaps seen to glide through the canopy like a breeze. Spider monkeys do not have fur around their eyes, and the artist captured this feature in the life-size representation.

The monkey wears the regalia of the Aztec wind god, Quetzalcoatl-Ehecatl. The figure wears beaded wristlets, anklets, and an elaborate collar fringed with marine shells, probably of the genus Oliva or Olivella. Below the collar hangs a representation of a pectoral, likely a cross-section of a conch shell, known in Nahuatl as ehecacozcatl, or "wind jewel," of which several examples are known from archaeological investigations and museum collections. Large ear ornaments dangle over the monkey's shoulders. These are composed of a round flare element and a curved pendant (Nahuatl: epcololli, "twisted shell"), also closely associated with the wind god. The monkey is seated on a quadrilateral base that is scalloped, possibly alluding to the rattle of a serpent.

Fig. 6. Left: Ehecatl regalia on spider monkey. Right: Crosscut conch-shell pendant (ehecacozcatl), A.D. 1486–1502. Mexico, Mexico City, Templo Mayor, Phase VI, Offering 125, Artifact 68. Mexica (Aztec). Gold, 3.3 x 2.9 x 0.4 cm (15/16 x 11/8 x 1/8 in.). Museo del Templo Mayor, 10-650646, Secretaría de Cultura—INAH

Spider monkeys were clearly of great ritual importance at the Templo Mayor—the sacred center of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire now mostly buried under Mexico City. A wind jewel pendant in the shape of a cross-section of a shell made of hammered gold, to be featured in the exhibition Golden Kingdoms, was excavated in association with spider monkey skin in Offering 125 at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (fig. 6). Another offering excavated at the Templo Mayor included flint knives wrapped in spider monkey pelt and decorated with shell ornaments identical to the ones depicted on The Met's statue in stone (fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Pair of ceremonial knives representing the god Ehecatl-Quetzalcoatl, A.D. 1486–1502. Mexico, Mexico City, Templo Mayor, Phase VI, Offering 125. Mexica (Aztec). Flint, jadeite, shell, obsidian, spider monkey skin, gold, and copal, right: 31 x 17 x 7.5 cm (12 3/16 x 6 11/16 x 2 15/16 in.); left: 23 x 12.7 x 3.5 cm (9 1/16 x 5 x 1 3/8 in.). Mexico City, Museo del Templo Mayor, Secretaría de Cultura—INAH

Surprisingly, this is not the first time that the two stone sculptures, which come from different donors, have been exhibited together. They originally formed a part of the collection of Pennsylvanian Jay C. Leff, as did The Met's recently acquired Aztec serpent labret. The Olmec kneeling figure and Aztec monkey were exhibited in 1959, and again at the Brooklyn Museum in 1966–67, eventually finding their way into two different New York collections by the 1980s. The generosity of these three donors will enhance our visitors' experiences with stone sculpture from ancient Mexico and an important style of Maya ceramic arts for years to come.

Resources

Coe, Michael D. The Maya Scribe and His World, fig. 63. New York: Grolier Club, 1973.

Easby, Elizabeth K. Ancient Art of Latin America from the Collection of Jay C. Leff. New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1966.

Fairservis, Walter Ashlin. Exotic Art from Ancient and Primitive Civilizations: Collection of Jay C. Leff, no. 341. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Institute, 1959.

Houston, Stephen D. The Life Within: Classic Maya and the Matter of Permanence, 43–44. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Reilly, F. Kent. "The Shaman in Transformation Pose: A Study of the Theme of Rulership in Olmec Art." Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University 48, no. 2 (1989): 4–21.

James Doyle

James Doyle is an assistant curator in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Follow James on Twitter: @JamesDoyleMet