Olmec Babies as Early Portraiture in the Americas

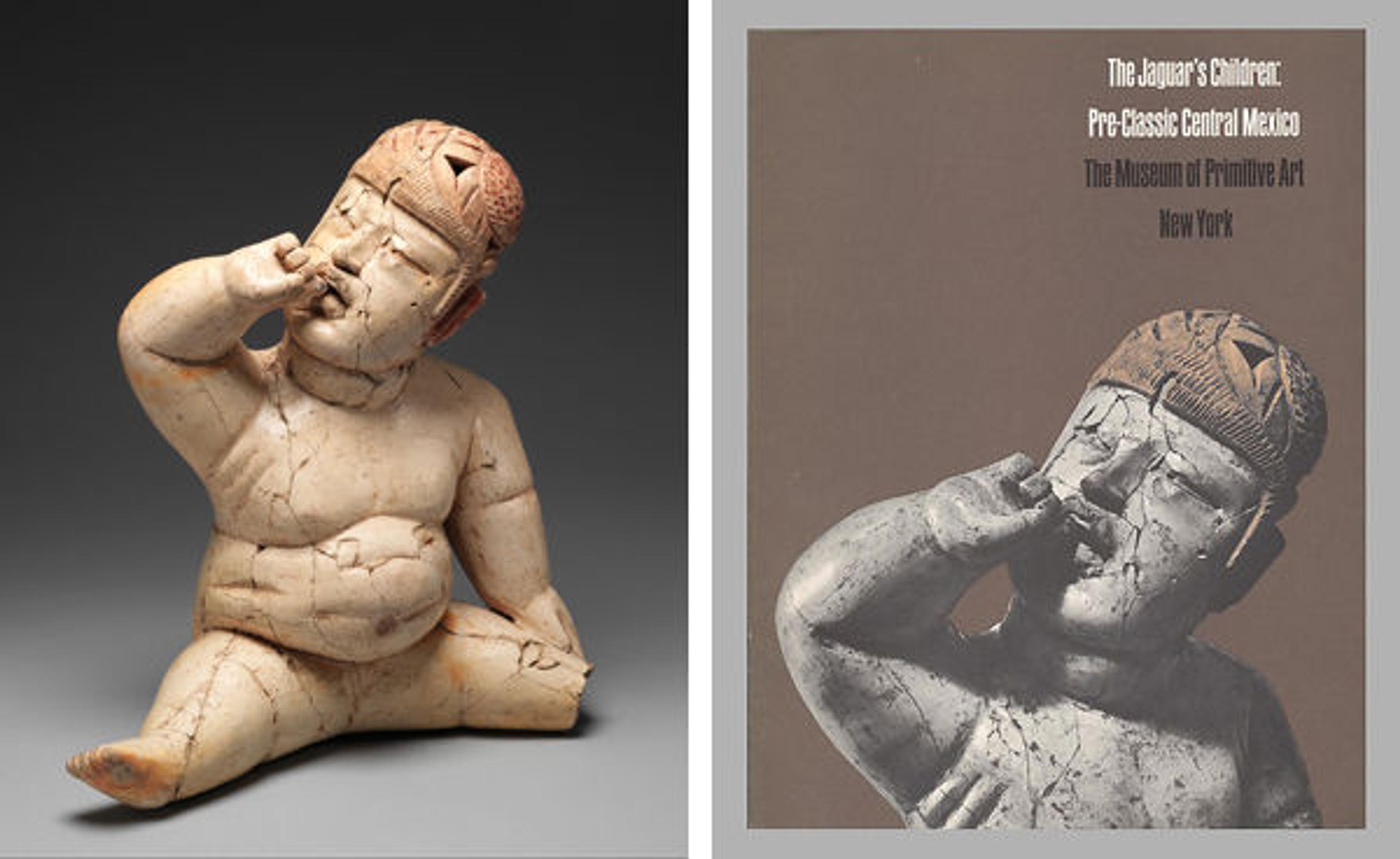

Fig. 1. Seated figure, 12th–9th century B.C. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Olmec. Ceramic, cinnabar, red ochre; H. 13 3/8 x W. 12 1/2 x D. 5 3/4 in. (34 x 31.8 x 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1134)

«One of the stars of gallery 358 and the recent exhibition The Nelson A. Rockefeller Vision: In Pursuit of the Best in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas is a seated figure of a chubby baby in the Olmec style from Central Mexico (fig. 1). As the Rockefeller exhibit pointed out, this is among one of the most celebrated Olmec ceramic works known to scholars, and was even selected as the cover model for the Museum of Primitive Art's landmark show on Preclassic Mesoamerica in 1965.»

The artist of this baby worked in a fine, white clay to produce a hollow figure subsequently decorated with a white slip and red pigment. This is perhaps the best example of this class of human figures displaying infantile characteristics. Usually without marked gender and seated with splayed legs and hands on thighs, these figures have the posture, body proportions, and fleshiness of human babies, though some are embellished with symbolic designs on their bodies and wear distinctive headdresses, such as the one here.

This pudgy infant is a remarkable example of one of the earliest traditions of portraiture in the Americas. The babies share some iconographic and stylistic characteristics with the monumental sculpture from the Gulf Coast Olmec centers of San Lorenzo and La Venta, but seem to have only been produced during the earlier Olmec florescence between about 1200 and 800 b.c.

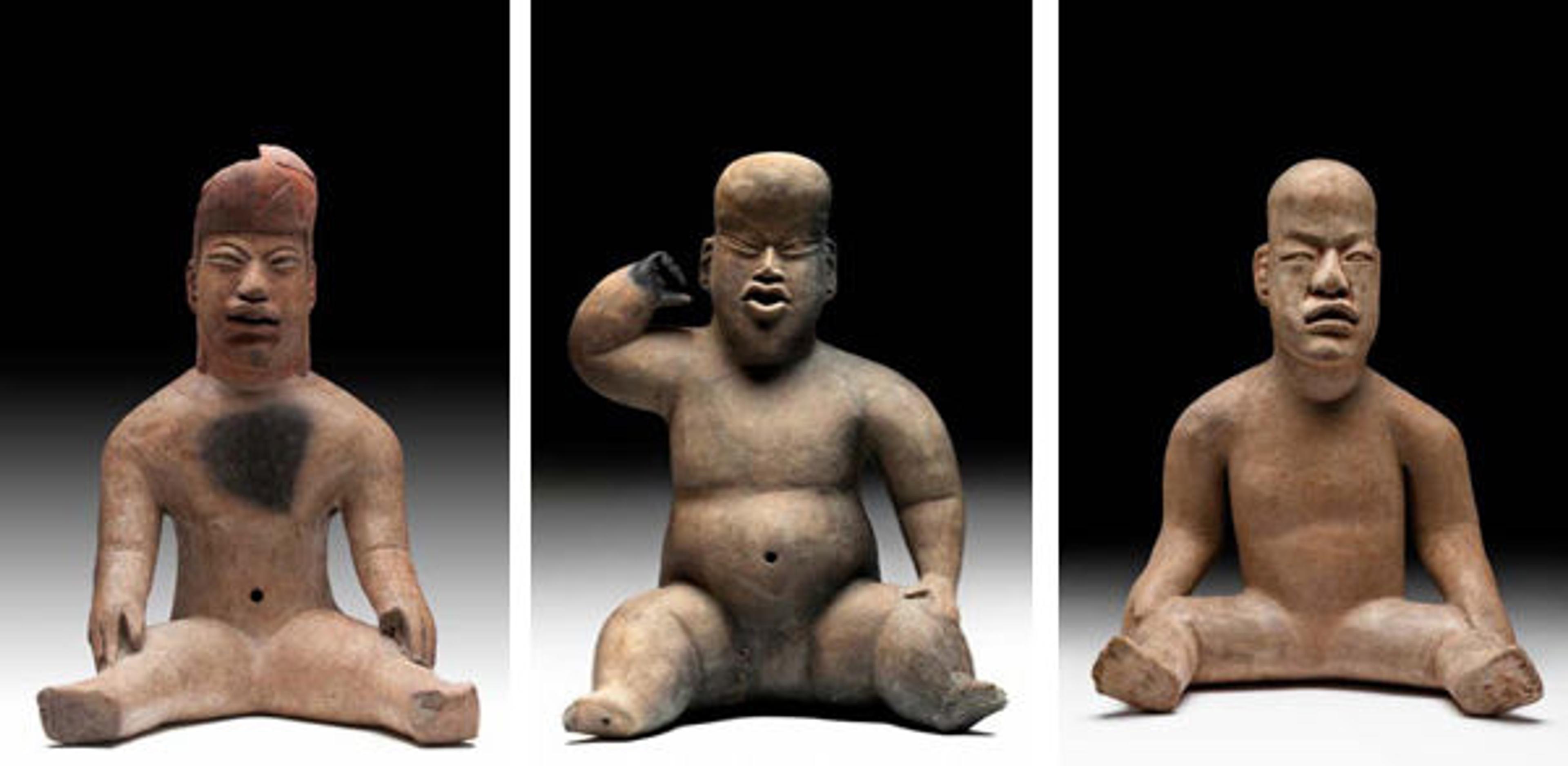

This figure is reported to be from the central highland site of Las Bocas, in the Mexican state of Puebla, where a number of Olmec-style ceramic objects have been found. Others have been found in burial contexts at the sites of Tlapacoya and Tlatilco, in the Basin of Mexico near modern-day Mexico City (fig. 2). Researchers encountered a well-known pair of sculpted individuals—nicknamed "the twins"—in Burial 12, Offering 6, at Tlatilco, which share many characteristics with the hollow, baby-face figurines. The fact that the vast majority of these baby-faced figures are only known from outside the Gulf Coast Olmec heartland poses a vexing question for scholarship: Are these really "Olmec" at all, or are they unique to the contemporaneous early cultures of Central Mexico?

Fig. 2. Seated figures from the collection of the Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico. Left: Seated figure. Central Highlands. H. 40.9 x W. 29.2 x D. 23.4 cm. Center: Seated figure. Tlapacoya. H. 44 x W. 33.3 x D. 22.9 cm. Right: Seated figure. La Cruz del Milagro, Veracruz. H. 30.3 x W. 24.6 x D. 16.5 cm

Perhaps an even more pressing unanswered question: Who exactly are these babies? Several possibilities exist. These could be portraits of elite babies, infantilized portraits of actual individuals, idealized portraits of deities or mythological characters, or some other type of ritual agent. They could be memorials to infants that left this world too early, or representative emblems of whole lineages. Regardless of the function or intent of the artists, they made the hollow sculptures very lifelike. The Metropolitan Museum's baby playfully gazes upward and raises a finger to its mouth, as if playing on the ground as the center of attention during a family gathering.

In some cases the ceramic effigies may have served as substitutes for actual infants in a sacrificial or dedicatory ritual, as there is compelling evidence of Olmec infant sacrifice or ceremonial burials. Mexican researchers working at the extraordinary waterlogged site of El Manatí ("the manatee") found dismembered bones of newborns, perhaps neonates, and a primary infant burial in the fetal position. These were associated with miraculously preserved wooden busts (fig. 3), rubber balls, and greenstone ax caches. The faces of the wooden busts are evocative of similar expressions found on the ceramic babies.

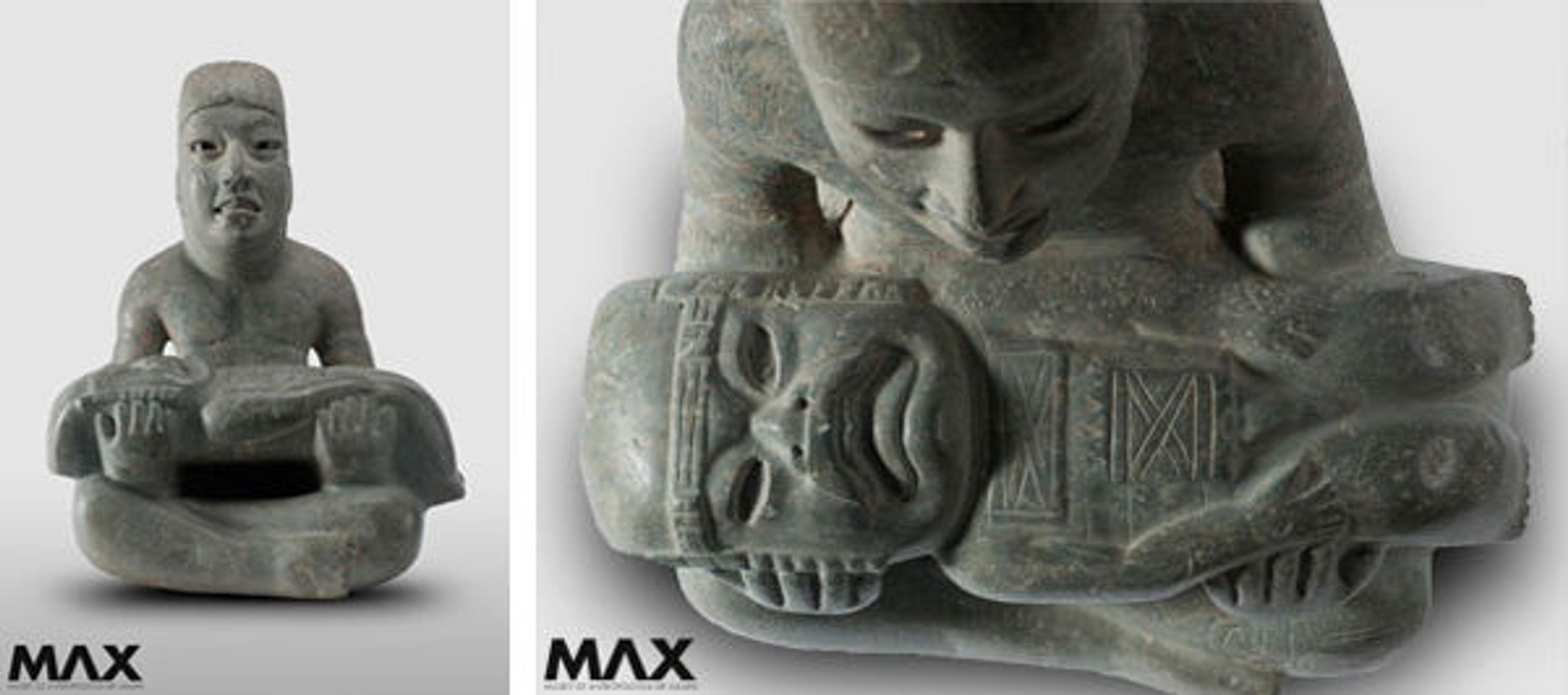

Left: Fig. 3. Wooden bust from El Manatí. H. 20 x W. 7 x D. 8 in. (50.8 x 17.8 x 20.3 cm). Centro INAH Veracruz. From Olmec Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico, edited by Kathleen Berrin and Virginia Fields; plate 34. Right: Fig. 4. Seated bench figure, 10th–4th century B.C. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Olmec. Serpentine; H. 4 7/16 x W. 2 1/4 x D. 2 1/8 in. (11.3 x 5.7 x 5.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.940)

Supernatural babies play a significant role in Olmec art. A serpentine figure on view in gallery 358 (fig. 4) shows an individual seated on a bench cradling a baby in his arms. In Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, scholar David Joralemon identified the distinctive shape of the throne as a cloud motif, similar to monumental reliefs carved at the site of Chalcatzingo, Morelos. The main personage sitting on the cloud throne has a large head with an incised hairstyle, and his oversized ears have drilled lobes, presumably for the insertion of removable ornaments. The baby itself is minimally adorned, but resembles babies known as the "were-jaguar" infants in scholarship of Olmec art. These infants often have feline features such as fangs and slanted, almond-shaped eyes.

The Met's small-scale figurine is similar in theme to the famous Señor de las Limas, a cross-legged individual cradling a "were-jaguar" infant across his lap (fig. 5). This infant has defined limbs and a sloping head with an incised cleft. Other babies with cleft heads have been identified as personified maize sprouts, a concept that persisted into the beliefs of the much later Classic Maya, who referred to youths as "ch'ok" or "sprout." The body of the main figure is incised with mythological characters on his shoulders and knees, emphasizing the Mesoamerican belief in the four corners and a center as an organizing principle of the Olmec worldview. The baby, this maize sprout made manifest, then stands in for the center of the world.

Fig. 5. El Señor de Las Limas, 10th–4th century B.C. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Olmec. Greenstone; H. 55 x W. 43.5 x D. 23 cm. Museo de Antropología de Xalapa, Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico (04017)

The preoccupation of Olmec peoples with child-rearing and the mythological connections between the life cycles of infants and agriculture transcend time and space. Today, visitors to the Mesoamerican art gallery are immediately drawn to the expressive baby figure and the seated figure holding the infant. As Andrall E. Pearson Curator Joanne Pillsbury points out in her 82nd and Fifth episode, "Face," contemporary viewers continue to appreciate the ideas of fertility and cyclical life found in masterpieces of Olmec art.

Additional Reading

Benson, Elizabeth P., and Beatriz de la Fuente, eds. Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1996.

Berrin, Kathleen, and Virginia Fields, eds. Olmec Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico. Los Angeles: LACMA, 2010.

Blomster, Jeffrey. "Context, Cult, and Early Formative Period Public Ritual in the Mixteca Alta: Analysis of a Hollow-Baby Figurine from Etlatongo, Oaxaca." In Ancient Mesoamerica 9 (2) (1998): 309–326.

———. "What and Where Is Olmec Style? Regional Perspectives on Hollow Figurines in Early Formative Mesoamerica." In Ancient Mesoamerica 13 (2002): 171–195.

Castro-Leal, Marcia. "The Olmec Collections of the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City." In Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson and Beatriz de la Fuente, 139–143. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1996.

Clark, John E., and Mary E. Pye, eds. Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2000.

Coe, Michael D. The Jaguar's Children: Pre-Classic Central Mexico. New York: Museum of Primitive Art, 1965.

Coe, Michael D., ed. The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 1996.

Covarrubias, Miguel. Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957.

Ortiz, Ponciano, and Maria del Carmen Rodriguez. "The Sacred Hill of El Manati: A Preliminary Discussion of the Site's Ritual Paraphernalia." In Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica, edited by John E. Clark and Mary E. Pye, 75–93. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2000.

Pillsbury, Joanne. "The Pan-American: Nelson Rockefeller and the Arts of Ancient Latin America." In The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 72, No. 1 (2014): 18–27.

Pool, Christopher A. Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Tate, Carolyn. Reconsidering Olmec Visual Culture: The Unborn, Women, and Creation. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

Taube, Karl. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2004.

James Doyle

James Doyle is an assistant curator in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Follow James on Twitter: @JamesDoyleMet