A Face is a Face is a Face: Beneath Picasso's Gertrude Stein

Isabelle Duvernois, Conservator, Department of Paintings Conservation, and Silvia A. Centeno, Research Scientist, Department of Scientific Research

In 1946, when Gertrude Stein bequeathed her portrait to The Met, it became the first painting by Picasso to enter the Museum collection—and it has remained the most celebrated.

Much has been written by Stein and other contemporary witnesses about this iconic portrait and the legendary eighty or more sitting sessions, the multiple erasures and restarts, that took place in 1906.[1] Stein recalls Picasso "using a uniform brown grey color, mixed some more brown grey, and then the painting began."[2] After one of the very early sittings, friends and family came to visit, and it was said that all were astonished by that first sketch and begged Picasso to leave it as it was. He did not. No photograph was taken and no description of it was ever written.[3]

Over the years, conservators and scientists have attempted to determine whether we could verify the stories and see that very first sketch underneath the portrait.[4]

X-radiograph detail of Gertrude Stein's face

Extensive reworking of Stein's face was revealed using available technology (X-radiography, shown above, and autoradiography), but because Picasso erased in between sittings, only traces of her earlier features remained.

Recent technology that visualizes the distribution of elements that compose pigments within the paint layers has enabled us to delve deeper into Picasso's painting process.

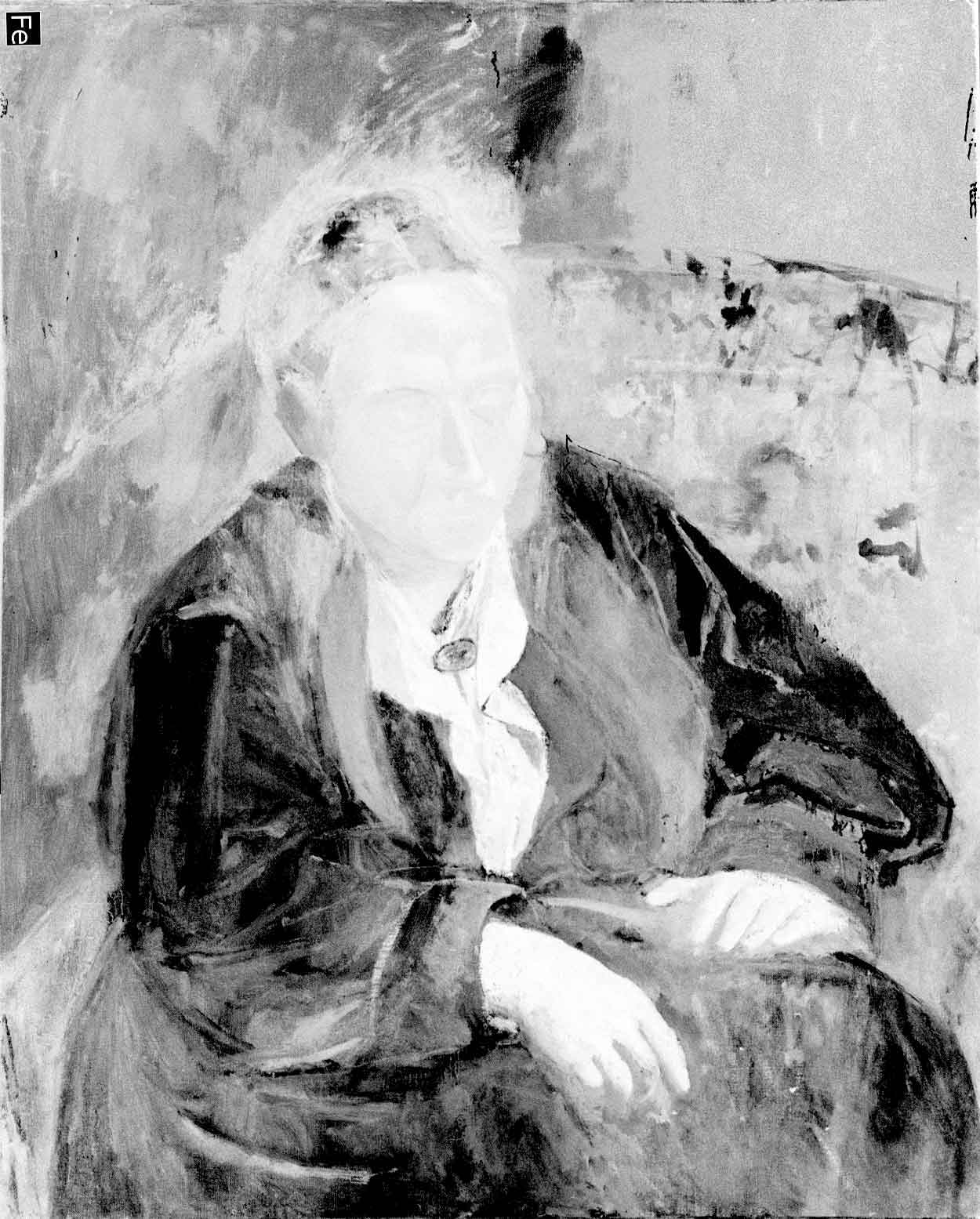

Map showing the distribution of iron contained in the brown-ochre pigment

A map showing the distribution of iron contained in ochre pigments (above) reveals that Picasso used brown earth pigments when he started painting Stein's portrait, emphasizing her long brown coat and the armchair on which she sits. Broad brush strokes, and fluid paint dripping down her sleeves as if arrested in time, vividly capture his speedy painting process, looking as fresh as the day he first sketched the portrait.

But the iron distribution map also shows how much he painted over some of the coat's features. Along the center, and around the sitter's hands, the paint application is muddier, indicative of active erasing and reworking. The erratic scoring marks and broad, gestural brushwork along the left side of the background indicate intense activity, in stark contrast to the right side, which the artist never altered past his first sketch.

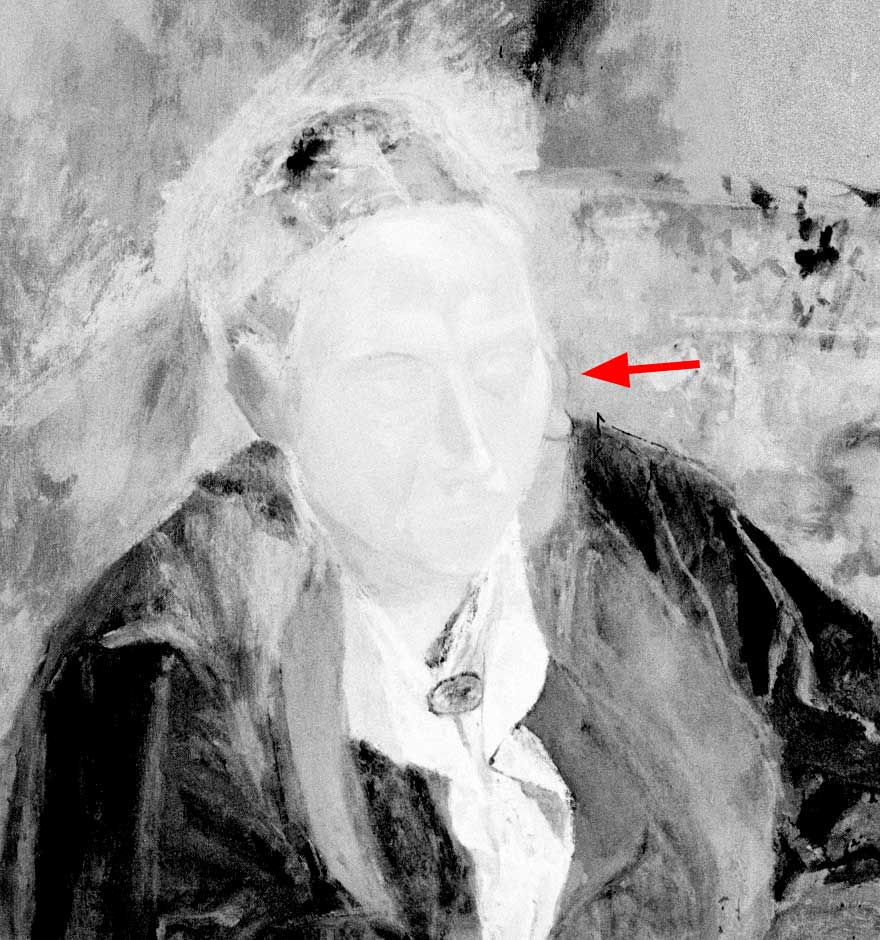

Detail of the brown-ochre pigment distribution map, with red arrow indicating the outline of an earlier profile

The evidence of Picasso's well-known struggle with Stein's face is also vividly apparent on this map. Her features are blurred and ghostly, like a photograph of a fast-moving subject.

The only clearly legible evidence of an earlier pose is the thin outline of a three-quarter profile along her left cheek—distinct enough to let us wonder whether this could be Picasso's first sketch.

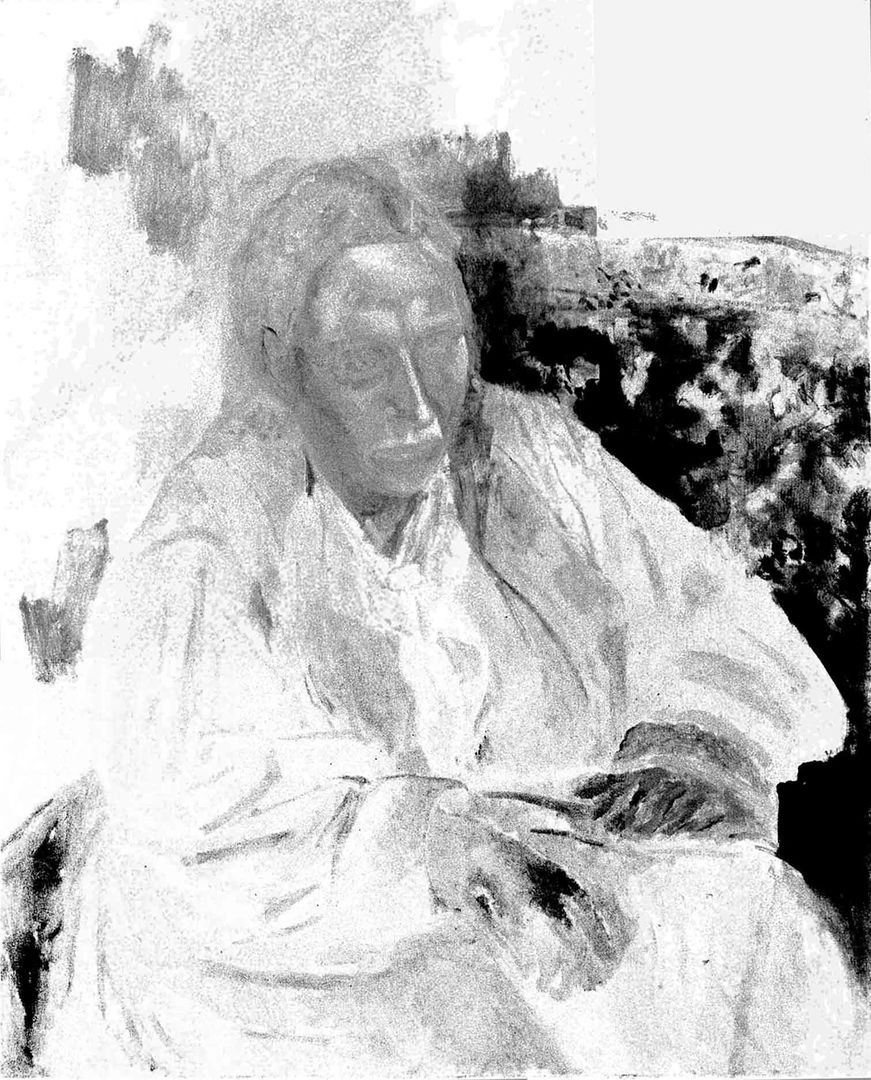

Map showing the distribution of mercury in the red pigment vermilion

Another area of reworking can be seen in Stein's hands, especially the left hand, as seen in a map (above) showing the presence of vermilion, a pigment usually mixed in flesh tones. Seven adjacent fingers visible in the map reveal how Picasso shifted the position of the hand on her lap, probably in relation to the changes he made to her face.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Gertrude Stein, 1905–6. Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 32 in. (100 x 81.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Gertrude Stein, 1946. (47.106) © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

At the time she posed for her portrait, Stein was writing the story of "Melanctha" in Three Lives. According to The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, a book she wrote later in the guise of her partner, "During the long poses, Stein meditated and made sentences."[5]

It is tempting to think that Picasso, consciously or not, had fallen under the spell of her idiosyncratic, modulated repetition and kept repainting her face and hands, repeatedly shifting them, ever so slightly. About her portrait, she later wrote: "For me, it is I, and the only reproduction of me which is always I, for me."[6]

The title plays on Gertrude Stein's famous utterance "Rose is a rose is a rose," from "Sacred Emily" (1913), and "A rose is a rose is a rose," in e.g. The World is Round (1938).

References

[1] Gary Tinterow et al., Picasso in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010): 108–113.

[2] Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in Writings, 1903–1932 (New York: Library of America, 1998): 706.

[3] Stein, Autobiography, 706.

[4] Lucy Belloli, "The Evolution of Picasso's Portrait of Gertrude Stein," The Burlington Magazine, vol. 141, no. 1150 (January 1999): 12–18.

[5] Stein, Autobiography, 710.

[6] Gertrude Stein, Writings, 1932–1962 (New York: Library of America, 1998): 8.

150th Anniversary: Conservation Stories

Go behind the scenes with iconic Met objects and see what happens when science meets art.

Celebrate the 150th anniversary with special events and projects all year long.