Powel Room

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1765–66

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate

The Powel Room, installed in Gallery 722, was originally located on the second story of a house that still stands today at 244 South Third Street in Philadelphia. Constructed in 1765–66 by Charles Stedman (1713–1784), a Scottish-born shipmaster and merchant, the house was sold to Samuel Powel (1738–1793) in 1769, at the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Willing (1743–1830).

Powel was the last mayor of Philadelphia under British rule and the first after the American Revolution (1775–83), so the couple hosted many members of the Continental Congress, including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and George Washington. The room is furnished with superb examples of Philadelphia Rococo-style furniture of the type that the Powels might have owned.

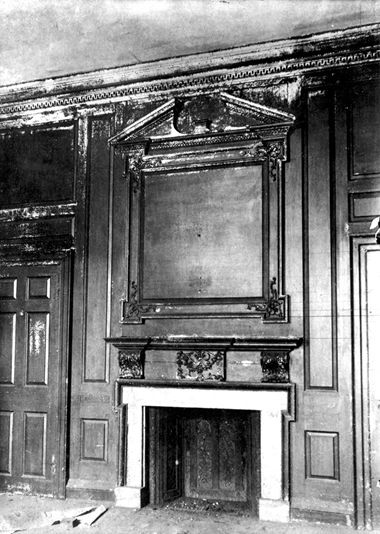

Image: Fireplace wall of the Powel Room.

Georgian-style town house

When Charles Stedman began building his house in 1765, the prevailing architectural mode in Philadelphia was an adaptation of the British Georgian style. The style was expressed differently in the various American cities along the Atlantic coast. The Powel House represents Philadelphia Georgian architecture at its best.

Described by the future president John Adams as a "splendid Seat" during a visit to Philadelphia in 1774, the three-bay, red-brick town house had a relatively plain, unbroken, symmetrical facade; shuttered sash windows with decorative keystones; and a paneled front door.

Image: The Powel House at 244 South Third Street, Philadelphia. Library of Congress

Georgian-style doorways

In a typical Philadelphia Georgian building, the front entrance is more elaborate than the rest of the facade. The paneled front door of the Powel House, topped with a fanlight and flanked by Ionic columns owes much to the forms and ornaments of ancient Roman and Greek buildings, as transmitted through the later work of Italian Renaissance architects.

The front door opened onto a spacious entrance hall with an elaborate staircase ascending to the second story, where the Museum's Powel Room was located. The Marquis de Chastellux, an officer who served with French forces in the Revolutionary War, observed in 1780 that the fine residences of Philadelphia "closely resemble the houses in London." Thomas Jefferson found Philadelphia houses even "handsomer" than those in London or Paris.

Image: The paneled front door of the Powel House as it appeared in 1976. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS PA, 51-PHILA, 25—4

Interior

According to insurance surveys taken in 1769 and 1785, the Powels' "Main House" had three stories, with a garret attached to a two-story back building. As was fashionable in England, the principal rooms were on the second story, where the absence of an entrance from the outside translated into maximum space. These rooms were also removed from the odors and dirt of the street, as well as the heat and smoke of the kitchen.

While the surveys do not identify the rooms' purposes, the second-story "Front Room" was probably a ballroom. It is now installed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Recent scholarship indicates that the "Back Room," on display at The Met, may have served as the best chamber, or "state" bedroom, intended for important visitors rather than family members.

Image: Conjectural floor plan of the Powel House. Courtesy of Kevin Greenland

Remodeling, 1769–71

Robert Smith designed Benjamin Franklin's house and several prominent public buildings, including Zion Lutheran Church, shown in this 1799 engraving by William and Thomas Birch. The New York Public Library

When the Powels took possession of Charles Stedman's house, they hired many of the finest craftsmen in Philadelphia to elaborate on the formal rooms, which had originally been decorated in a relatively simple manner. One such artisan was Robert Smith, Philadelphia's premier carpenter-builder.

Smith, in turn, employed four leading Philadelphia carvers: Hercules Courtenay, the partners Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, and James Reynolds. Powel kept careful financial records documenting that he paid Courtenay a total of £60 for carvings in his "dwelling house" and that Reynolds was paid for architectural carving.

Rococo carving

Left: A design source for the Powels' mantel may have been Plate XII in Batty Langley's The City and Country Builder's and Workman's Treasury of Designs (1756). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of W. Gedney Beatty, 1941 (41.100..94). Right: Powel Room chimneypiece

In Philadelphia houses, elaborate Rococo-style carving tended to appear on fireplaces—the sole source of heat and a natural gathering place. Carving was often executed on the fireplace trusses: scrolled consoles supporting the mantel shelf. The richly carved mantel and overmantel of the Powels' fireplace is one of the finest extant examples of eighteenth-century Philadelphia woodwork. Museum curators chose to paint some of the details a green to imitate verdigris, the blue-green patina visible on oxidized metals, increasing the visual impact of the carving against the room's tan woodwork.

Setting

Left: The Powel House, as illustrated in an engraving by Thomas and William Birch, entitled View in Third Street, from Spruce Street, 1800. The New York Public Library. Right: Map of Philadelphia, 1762, by Nicholas Scullwith the location of Powel House circled in red. The New York Public Library.

The Powel House was built on the west side of South Third Street, midway between Spruce and Walnut Streets. This fashionable neighborhood changed dramatically over time. By the early twentieth century, the house was serving as a warehouse for a business that imported and exported horsehair and bristles. When the structure was slated for demolition in 1931, a local resident formed the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks in order to purchase the property. The house is still maintained by the organization and is open to the public.

The Stedmans

On January 1, 1748/9 Charles Stedman married Ann Graeme at Philadelphia's Christ Church, where he served as a vestryman for over twenty-five years. William Strickland (1788–1854). Christ Church, 1811. Oil on canvas. Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, Courtesy of Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection, Bridgeman Images

Charles Stedman (1713–1784) and Ann Graeme Stedman (d. 1766) were the first owners of the Powel House. Charles was a Scottish-born shipmaster and businessman who, along with his brother Alexander, was involved in merchandising, ironworks, and real estate.

By 1765 the brothers had acquired a level of wealth and position in the Philadelphia community that enabled them to build fine new homes. Charles Stedman chose the South Third Street location, but even before the house was finished, his fortunes began to wane. In the spring of 1766 Ann Graeme Stedman died. Charles Stedman dissolved the partnership with his brother and, in the fall, placed his house on the market. After three years, he finally sold the residence to Samuel Powel for £3,150 in order to satisfy his creditors.

The Powels

Samuel and Elizabeth Willing Powel were the second owners of the house, having purchased it soon after their wedding on August 7, 1769. Their union brought together two of the most prominent families of Philadelphia. By all accounts, the marriage was a happy one. The couple shared an interest in style, politics, and high society, and their home was the scene of many elegant dinner parties.

Sadly, their two sons both died in infancy. To preserve the Powel family name, the couple focused on the son of Elizabeth's sister Margaret Hare. This nephew eventually took legal action to change his name from John Powel Hare to John Hare Powel, and it was he who received the bulk of Elizabeth's estate when she died on January 17, 1830.

Image: The Powel House, with later addition is seen here in this detail of an engraving by Thomas and William Birch entitled View in Third Street, from Spruce Street, 1800. The New York Public Library

Samuel Powel

Samuel Powel (1738–1793) was a wealthy, privileged young man from one of the best-established families in Philadelphia. After graduating from the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) in 1759, he embarked on a grand tour of Europe—a ritual had become, by the mid-eighteenth century, an essential part of a gentleman's education.

Not long after returning to Philadelphia, Powel married Elizabeth Willing and began his career in public office. His father-in-law’s flourishing mercantile business gave him political clout, which culminated in his election as mayor.

Image: During his travels abroad, Powel had his portrait painted by the gifted Swiss-born artist Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807). In the portrait, he holds an architectural plan for an unidentified building. From Edgar Peters Bowron and Joseph J. Rishel, eds., Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, (2000)

Elizabeth Willing Powel

Elizabeth Willing Powel (1743–1830) was known for her intelligence, wit, style, and occasional sharp tongue. She was the sixth of eleven children born to Charles Willing and Ann Shippen Willing of Philadelphia. The Willings believed in the power of a good education—Elizabeth’s eldest brother, Thomas, studied for the bar at the Inner Temple, one of the four Inns of Court in London. The Willing sisters were probably educated at home by private tutors, as was usual for the time.

Whatever training she received, Elizabeth must have been well taught, as Benjamin Rush dedicated his Thoughts upon Female Education (1787) to her. Many other luminaries, including Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, the Marquis de Chastellux, and George and Martha Washington, wrote about her fascinating personality.

Image: Matthew Pratt (1734–1805) painted this portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powel in 1793. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, Henry D. Gilpin Fund

Philadelphia Craftsmen

Detailed records kept by Samuel Powel indicate that many of Philadelphia's leading craftsmen to contributed their artistic talents to improving his residence. These included the following men:

Robert Smith (1772–1777)

An emigrant from Scotland, Smith was on of Philadelphia's leading carpenter-builders, responsible for several of the city's public buildings, including Zion Lutheran Church (1766–69), St. Peter's Church (1758–61), Carpenters' Hall (1770–75), and the Walnut Street Jail (1773–76). His domestic projects not only included the alterations to the Powel house, but also Benjamin Franklin's house, located off the south side of Market Street, west of Third Street.

Hercules Courtenay (1744–1784)

Courtenay was a London-born carver who apprenticed to Thomas Johnson, one of the city's leading proponents of the Rococo style. Courtenay immigrated to Philadelphia in 1765, where he was a woodcarver and gilder best known for his Rococo ornamentation. After working in the shop of cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph, he became master of his own shop from 1769 to 1779, after which he was a tavern keeper until his death in October 1784.

James Reynolds (c. 1739–1794)

According to the Pennsylvania Gazette, James Reynolds, a carver and gilder from London, arrived in Philadelphia in 1766. Reynolds established a workshop on Front Street between Chestnut and Walnut Streets where he offered imported and shop-carved looking glasses. Period documentation and surviving examples show he carved elaborate works for prestigious Philadelphia families including, the Cadwaladers, the Chews, the Pembertons, the Penns, as well as for George Washington.

Nicholas Bernard (1732–1788) and Martin Jugiez (died 1815)

Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez were immigrant carvers, active in the late 1750s to 1783, who contributed to furniture and architectural commissions at Philadelphia's most distinguished sites, including St. Peter's Church (1763), Mount Pleasant (1764), Cliveden (1766), and the homes of Samuel Powel (1769) and John Cadwalader (1771). The earliest advertisement of their partnership appears in 1762 and features imported goods and those made by the established carvers. Bernard and Jugiez would expand their clientele beyond Philadelphia into New York, the Carolinas, and Virginia.

Image: Attributed to Benjamin Randolph (American, 1737–1792), possibly carved by Hercules Courtenay (American (born England), 1744–1784). Side Chair, ca. 1769. Mahogany, northern white cedar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sansbury-Mills and Rogers Funds, Emily Crane Chadbourne Gift, Virginia Groomes Gift, in memory of Mary W. Groomes, Mr. and Mrs. Marshall P. Blankarn, John Bierwirth and Robert G. Goelet Gifts, The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, by exchange, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, by exchange, and funds from various donors, 1974 (1974.325)

Entertaining the Founding Fathers

Before and after the American Revolution, the Powels presided over grand dinner parties. In his two-volume book Travels in North-America (1786), the Marquis de Chastellux praised Elizabeth Powel for "her taste for conversation and the truly European manner in which she used her wit and knowledge."

When George Washington was in Philadelphia as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, the Powels formed a close friendship with him and his wife, Martha. Upon hearing that Washington was considering retiring from the presidency after one term, Elizabeth Powel sent him a letter urging him to continue, asserting that "you are the only Man in America that dares to do right on all public Occasions." Although Washington never replied to this letter, it survives in his archives.

Image: Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827). George Washington, 1779–81. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Collis P. Huntington, 1897 (97.33)

The colonial revival

The Powel Room as it appeared in 1924 when first installed in the American Wing from R. T. H. Halsey and Elizabeth Towers’s The Homes of Our Ancestors (1925)

In tribute to the original founders of the American Wing, the Powel Room still appears very much as it did when it first opened to the public in 1924. Curators had purchased the room in 1917 for its fine Georgian-style woodwork and its association with luminaries such as George and Martha Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, all of whom had been entertained by Samuel and Elizabeth Powel.

The founders of the American Wing were pioneers in the way they viewed America's past and the manner in which they presented antiques to the public. Their idea of what was beautiful and historically significant was a reflection of the Colonial Revival movement. Adherents to this movement respected the fine craftsmanship, simplicity of form, and restrained ornamentation of colonial decorative arts and architecture. Historic figures were revered, as were objects associated with their lives. The American Wing's founders sought to present colonial objects as expressions of national taste and culture. These pieces were often displayed in architectural settings, known as period rooms, consisting of interior woodwork produced in a similar time period. The chief goal in creating such rooms was to provide an aesthetically pleasing presentation rather than one that completely conformed to historical accuracy. The American Wing's Powel Room is preserved as an example of this approach to furnishing period rooms.

A bold vision

Many years in the planning, the American Wing was the brainchild of a trio of like-minded men: Robert W. de Forest, president of the Museum; R. T. H. Halsey, an inveterate collector and Museum trustee who served as the Wing's de facto curator; and Henry W. Kent, secretary to the Board of Trustees.

De Forest, Halsey, and Kent set out to prove that "American domestic art was worthy of a place in an art museum." Together, they oversaw the inauguration of a building that introduced a completely new way of displaying American decorative arts and demanded that the objects be respected for their craftsmanship and beauty. Each man also had his own particular ambition for the American Wing. The end result was a synthesis of their goals.

Image: The facade of the Branch Bank of the United States (built by Martin E. Thompson between 1822 and 1824) as installed as the entrance to the American Wing in 1924

De Forest: Bringing good art into the home

Left: Robert W. de Forest in a photograph taken around 1929. American Wing files. Right: Art students sketching in the Powel Room

Robert Weeks de Forest (1848–1931) was a philanthropist before he was a collector. He believed that the mission of the American Wing was, first and foremost, to educate. He valued beauty and industry above history and believed deeply in the Museum's founding principles: "encouraging and developing the study of fine arts, and the applications of arts to manufacture and practical life."

After the opening of the American Wing, he published articles and delivered speeches promoting the new galleries as a model of good taste and encouraging the production of furniture based on American historical models. In his own words, "Much as I am interested in bringing art to the museum, I am more interested in bringing good art into the home... A beautiful room with harmonious furnishings can bring calm, joy and happiness."

Halsey: Educating new Americans

Left: R. T. H. Halsey in an undated family photograph. Collection of Carol Halsey Harbour. Right: Schoolchildren learning about American art at the Museum, ca. 1924. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

R. T. H. Halsey (1865–1942) saw the American Wing as a place to teach newly arrived immigrants about American history and values, so that they might assimilate more easily. At the time, many newcomers to New York were Italian or Eastern European, poor, and relatively uneducated. While settlement houses and social service agencies could help with bodily care, the American Wing could help foster interest and pride in the immigrants' adopted home.

In his speech at the opening of the American Wing, Halsey explained: "A journey through this new American Wing cannot fail to... bring with it a spirit of thankfulness that our great city at last has a setting for the traditions so dear to us and so invaluable to the Americanization of many of our people, to whom much of our history has been hidden in a fog of unenlightenment."

Acquiring the Powel Room

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the neighborhood surrounding the Powel House had become a center for business. The house itself was used as a factory and shop for horsehair products. Many of the early architectural features had been removed. The back room on the second floor, however, remained mostly intact, and the Museum purchased it in 1917 for the planned new American Wing.

Image: Fireplace wall before coming to the Museum

Installing the Powel Room

The Powel Room today

The architecture of the Powel Room was accurately installed in 1924, in terms of size and layout. The only exception was the addition of a door that enabled Museum visitors to circulate. The tan paint on the woodwork is appropriate to the period, but the curators were not able to positively identify the exact shade of the original paint.

None of the furniture in this room was actually owned by the Powel family, and no inventory of the house's contents has been found. Period documents suggest that the Powels furnished their home with a mixture of American-made pieces and English examples purchased by Samuel during his grand tour. Although new research suggests that this room likely served as a bedroom for the Powels' prestigious guests, the Museum has chosen to keep it furnished as a parlor to reflect the Colonial Revival taste that influenced its original installation.

Wallpaper, draperies, and carpet

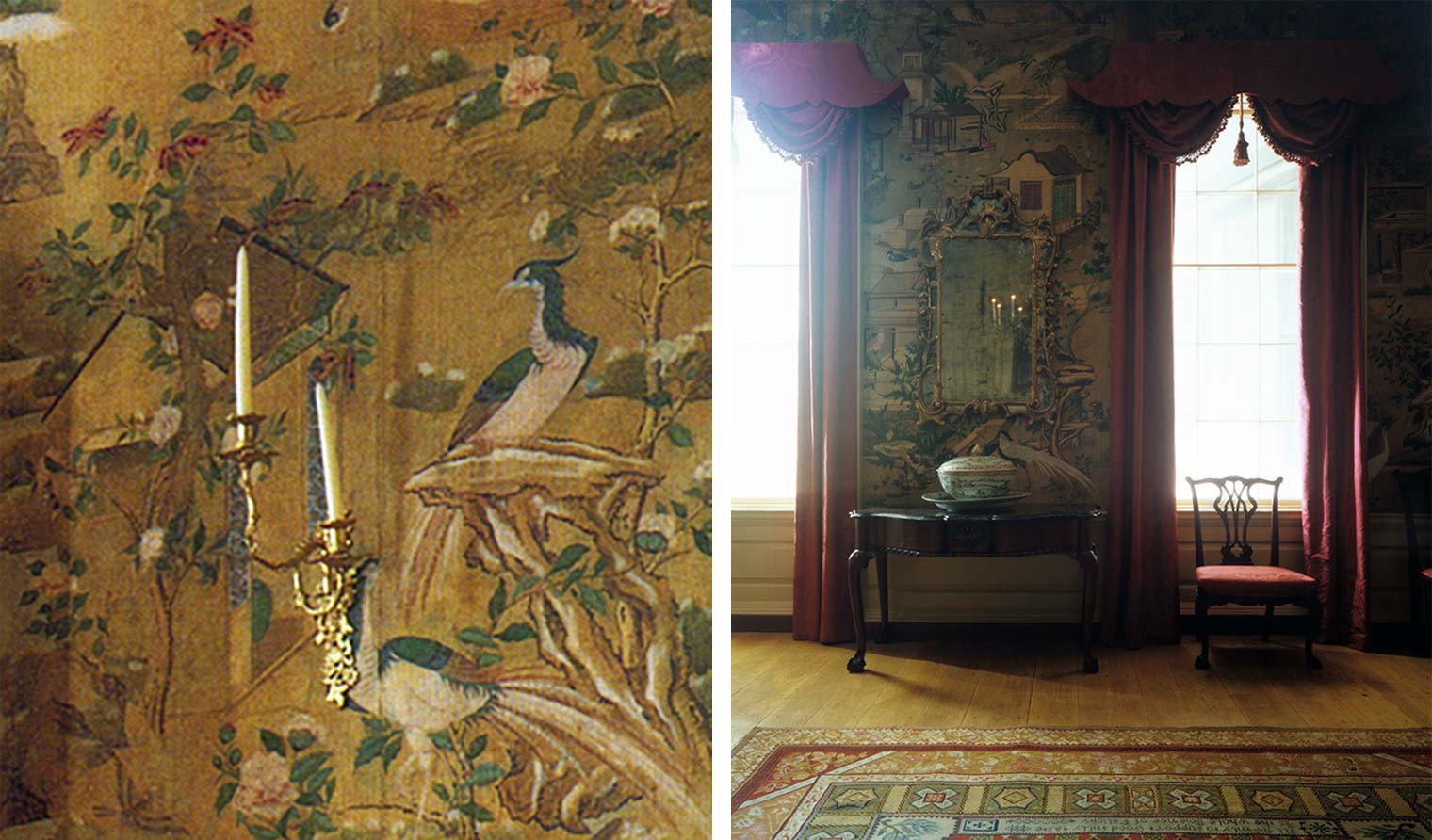

Left: The hand-painted wallpaper is of the period but not original to the Powel House. Right: The room's Chinese wallpaper inspired the pagoda-like valances of the draperies

The eighteenth-century Chinese hand painted wallpaper is not original to the room, but it was included in the 1924 installation of the room. Just seven years later, the Philadelphia Society for the Preservation of Landmarks saved the Powel House from destruction and reported that the plaster walls may have originally been painted a "beautiful blue." The wallpaper has remained on the walls to illustrate the ideal colonial parlor as conceived by the Museum's early curators.

Museum curators designed the red damask draperies many years ago to harmonize with the Chinese wallpaper. The eighteenth-century English needlework rug was added to the room in 1980, although the Powel House probably contained less expensive woven carpets, laid wall-to-wall over the original yellow-pine floor.

Ceiling

The Ballroom from the Powel House, as installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

When the Museum acquired the room it retained its original plain plaster ceiling, yet the Museum's curators desired a more elaborate ceiling to enhance visitors' perceptions of the house's grandeur. The ceiling of the ballroom from the Powel House, now installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, features elaborate plaster decoration attributed to Scottish-born craftsman James Clow. Before installing the Powel Room in the American Wing, the Museum took molds of the ballroom ceiling and created a modified design, adjusting the scale and eliminating elements, to make it fit onto the ceiling of the smaller room at The Met.

Origins of the Rococo style

Left: Rococo room from the Hôtel de Varengeville, Paris, ca. 1740. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1931 (32.53.1). Right: Rococo dining room from Kirtlington Park, England, ca. 1748. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Samuel H. Kress Foundation, 1958 (58.75.1–.22)

The Rococo style originated in Italy and became popular in France during the 1730s, as seen in the Museum's period room from the Hôtel de Varengeville in Paris. The style then spread to England in the 1740s, evidenced by the dining room from Kirtlington Park. It took another decade for the style to become popular in America, crossing the Atlantic through imported objects, immigrant craftsmen, and pattern books.

Philadelphia Rococo style

Commerce and trade made Philadelphia prosperous in the mid-1700s. The city's population exceeded that of Boston or New York, reaching 28,500 by 1774. This period also marked the height of the Rococo style, providing plenty of job opportunities for carvers and artisans who had emigrated from London. As a result, Philadelphia produced the most thoroughly English interpretation of the Rococo style in America.

This liberally embellished trade card of Benjamin Randolph is a spectacular representation of the American Rococo style. Note the intricate furniture designs around and within the cartouche, displaying curved cabriole legs, scrollwork, claw-and-ball feet, and other types of flora and fauna, often in asymmetrical compositions. All are characteristics American Rococo furniture in the "modern taste."

Image: James Smither, a Philadelphia engraver, created this trade card for the cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph in 1769. The Library Company of Philadelphia

Chippendale's influence

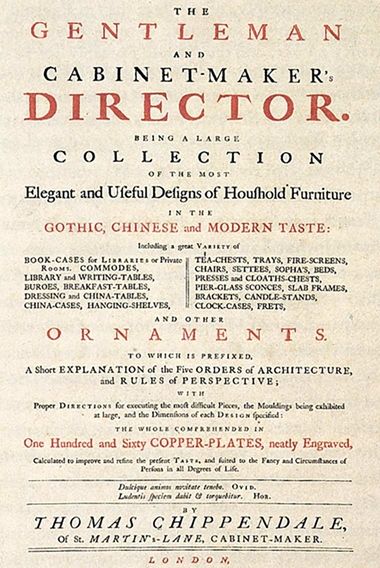

In 1754 the London cabinetmaker and designer Thomas Chippendale published the first edition of The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director, containing 160 engraved plates. The third edition of 1762 included a total of two hundred plates, of which 106 were new. To this day, English and American Rococo furniture is popularly called "Chippendale."

Image: Title page of the first edition of Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (London, 1754)

Philadelphia side chairs

Left: Side chair, 1760–90. American, Philadelphia. Mahogany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.51.10). Right: Side chair, 1760–90. American, Philadelphia. Mahogany, white cedar, tulip poplar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, 1932 (32.55.5)

As colonial America's most cosmopolitan city, Philadelphia embraced and emulated high-style English design. The Powel Room exhibits a selection of side chairs made in Philadelphia that reflect this taste. On the chair pictured at left, the squat proportions of the back and the carved rail skirts are suggestive of English work, but the oval rear legs, side rails with through tenons, and the design and carving on the back are in the classic Philadelphia manner. The refined carving that accentuates the integrated design of the crest and splat represents the fullest development of the Gothic splat pattern in Philadelphia. The hairy paw feet are a restoration.

The chair at right is an example of the trefoil-pierced splat chairs that were especially popular in Philadelphia. Except for the scroll-like central part of the crest rail, the design of the entire back was taken line for line from Plate X of the first edition of Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker's Director (1754). The skirt and knee brackets were copied from two different plates that were included in the 1762 edition. The Director was widely available in America, but its stylistic influence was strongest in Philadelphia.

Desk and bookcase

Among the most impressive forms of American furniture, the desk and bookcase was a symbol of its owner's mercantile and intellectual achievements. On this example, a carved finial bust of a young woman, likely a literary figure, emerges from the broken-scroll pediment at the top. The square-paneled doors of the bookcase and slat-front top of the desk open to reveal shelves, cubbyholes, and slots for the storage of documents, books, and correspondence.

A surviving invoice confirms that this desk and bookcase was heavily restored in 1898, at the height of the Colonial Revival era, before it entered the Museum's collection. The original appearance of the object and full extent of the restoration remains unknown, but the late nineteenth-century cabinetmaker who executed the work was undoubtedly influenced by a variety of designs for decorative carving that appeared in Thomas Chippendale's The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754).

Image: Desk and bookcase, 1865–90. Philadelphia. Mahogany, yellow pine, red cedar, white oak, tulip poplar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1918 (18.110.1)

Desk and bookcase with slant front door to the desk opened.

Tilt-top tea table

Types of furniture associated with social interactions—especially the serving and drinking of tea—were indispensable components of fashionable parlors during the second half of the eighteenth century. Tilt-top tea tables, featuring a single pillar supported by three legs, could be placed against a wall for storage when their tops were tilted to a vertical position.

Image: Tilt-top tea table, 1765. Philadelphia. Mahogany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1918 (18.110.13)

Margaret Strachan (Mrs. Thomas Harwood)

Margaret Strachan (1747–1821) was the daughter of William Strachan of London Town in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. In 1772, she married Thomas Harwood, who served as treasurer of the Western Shore of Maryland from 1776 until his death in 1804. Although undated, the portrait of Margaret Strachan by Charles Willson Peale was probably executed prior to the Strachans' marriage. It appears on a "payment due" list compiled by Peale for the period 1770 to 1775. A companion portrait of Thomas Harwood was painted around 1775 and is now in the collection of the Winterthur Museum in Delaware.

Image: Charles Willson Peale (American, 1741–1827). Margaret Strachan (Mrs. Thomas Harwood), ca. 1771. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1933 (33.24)

Looking glass

Elaborately carved Rococo frames were either gilded, like this one, or painted white to be hung against a darker-colored wall. Here, the confection of Rococo motifs includes C-scrolls at the four corners and pendants of leaves and flowers on two sides.

Image: Looking glass, 1745–80. England or Philadelphia. Gilded gesso, red pine, white pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1935 (35.22)

Covered punch bowl and platter

Left: Covered punch bowl, 1745–55. China. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1940 (40.133.1a, b). Right: Platter, 1745–55. China. Porcelain. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1940 (40.133.2)

This monumental punchbowl, with its original cover and platter, must have been one of the most ambitious porcelains to grace an American colonial household. We can only speculate as to how the bowl, whose decoration indicates it was made for the Swedish market, found its way to a prominent Charleston family during the eighteenth century. It was listed among the effects of Mary Brandford Bull, upon her death in 1772, as "1 large China Bowl Dish & Cover." The Bulls, one of Charleston's wealthiest families, lived in the grand style. The bowl descended in the family and ended up in Philadelphia by 1790. The detailed painted scene on the platter is based on a 1691 engraving of Läckö Castle on Sweden’s Lake Vänern. Two other Swedish châteaus drawn from earlier print sources are represented on the bowl as well; the cover features two Swedish churches in a landscape with huntsmen, fishermen, and sailors.

Lighting fixtures

Cut-glass chandeliers were a rarity in colonial America, but it is possible that the Powels may have owned such a fixture. The eight-arm chandelier on view, imported from Ireland, is composed of dazzling cut-glass that would have enhanced the dim light offered by eighteenth-century candlelight.

Also on view is a pair of gilt-bronze wall-mounted sconces. These examples exhibit the playful, naturalistic, asymmetrical ornament typical of the Rococo style. Generally, wall sconces were viewed as relatively safe since they, unlike candlesticks, could not be knocked over.

Image: Chandelier, 1770–80. Irish. Glass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Russell Sage Gift, 1948 (48.159)

Marble-slab table

Marble-slab table, 1760–70. Philadelphia. Mahogany, marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund; The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves and Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, by exchange; and funds from various donors, 1961 (61.84)

This table was made for the Philadelphia merchant Benjamin Marshall (1737–1778) at the time of his 1761 marriage to Sarah Lynn (1739–1797). Marble-slab tables were used for serving beverages and hot foods. Note that the skirt of this example is finished on only three sides, since the back of the table faced the wall.

Hot-water Urn

Introduced to tea equipage in the 1750s, the silver hot-water urn kept water hot with a heated rod or block of cast iron inserted inside the urn. The spigot tap avoided the need to lift and tilt a heavy kettle. In her journal entry of March 11, 1785, Nancy Shippen of Philadelphia rejoiced in "the most agreable [sic] chit-chat manner, [over] a very good dish of Tea."

Image: Louisa Courtauld (British, 1729–1807). Hot-water urn, 1765–66. London. Silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lilliana Teruzzi, 1966 (66.192.1)

Stool

American stools are remarkably rare, particularly those with cabriole legs and Rococo carving. Although the claw feet of this example are in the English manner, the stool appears to be of New York manufacture. The bow shape of the scalloped edges of the long rails was a popular motif in eighteenth century New York, and the flat carving with gouge-like finishing strokes on the knees is typical of local practice. The use of American beech also distinguished the stool from its English counterparts.

Image: Stool, 1750–90. Probably New York. Mahogany, American beech. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Joseph Kindig Jr., 1969 (69.208)

Needlepoint carpet

Needlepoint carpet, 1764. England. Wool. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Clara-Lloyd Smith Weber Gift, 1980 (1980.1)

Rugs and carpets were a considerable luxury in colonial America. Until the mid-eighteenth century, owners spread valuable imported rugs over tables rather than subjecting them to wear on floors. However, the size of this large, cross-stitched English carpet, decorated with floral and geometric motifs, indicates that it was intended for the floor. There are quotations from Edward Young's Night Thoughts (1742–45), a popular poem about life, death, and immortality, stitched into one of the carpet's inner borders.

American Georgian Interiors

(Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

Georgian design, which was characterized by an adherence to theories of order, symmetry, and proportion drawn from classical models during the Renaissance, represented a significant departure from earlier English decorative traditions.

American Furniture, 1730–1790: Queen Anne and Chippendale Styles

During the second quarter of the eighteenth century, the bold turnings, attenuated proportions, and dynamic surfaces of the Early Baroque, or William and Mary, style were subdued in favor of gracefully curved outlines, classical proportions, and restrained surface ornamentation.