Alexander Danilovich Menshikov (1673–1729)

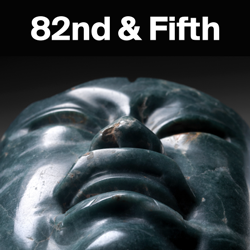

Finely detailed armor, a fluttering jabot, and an extravagantly combed wig set off the smoothly burnished face of the military commander portrayed in this wooden bust. His direct gaze is emphasized by the scooped truncation of his cuirass, which slices aggressively forward beneath it. The head turns slightly, against the flow of the lace cravat, imparting a sense of movement. Beneath the soft elements of lace and hair, sharply engraved images appear on the breastplate. The enwreathed ovals have been identified as scenes of Alexander the Great and his close friend Hephaestion at the tent of King Darius (to the viewer’s left) and the Justice of Trajan (slightly obscured, to the viewer’s right). Medallions on the pauldrons of Alexander the Great (left) and of the emperor Trajan (right) repeat the principal military figures seen in the ovals. Livia Drusilla, wife of Augustus Caesar (erroneously paired with Alexander), and Plotina, Trajan’s wife, occupy the pauldrons on the back of the cuirass.

The identity of this exceptional bust’s subject and of its maker puzzled scholars until research by Wolfram Koeppe and Marina Nudel resolved some of its mysteries.[1] The medium, which at first appeared to be boxwood, is in fact red pine stained to look like boxwood.[2] Sections of the bust were assembled with metal clips, a technique used by craftsmen accustomed to working with dense materials like boxwood or ivory that were only available in small pieces. While red pine is native to northern Europe, the Baltic region, and Russia, this method of construction is most often associated with woodworking in southern Germany and Austria. An explanation for this discrepancy is found in the biography of the man Koeppe and Nudel identified as the subject of the bust: a Russian known to have employed German and Austrian artists, Alexander Danilovich Menshikov. Of modest background and beginnings, Menshikov caught the eye of Czar Peter the Great when he was about twenty. He rose quickly through the ranks to become Commanding General Field Marshal of the Russian armies and was eventually appointed governor of Saint Petersburg. [3] His military prowess distinguished him, and his close friendship with the czar brought him to the pinnacle of wealth and power. He was made a count in 1702 and a prince in 1705 and became virtual ruler of the country for several years after Peter’s death in 1725. But in 1729 his enemies, the old Russian nobility, succeeded in having him exiled, and he died in Siberia that same year.

As Koeppe and Nudel noted, the wooden portrait bears a striking similarity to painted, etched, carved, and modeled images of Menshikov.[4] The exaggerated wig fashionable in the early eighteenth century appears in all of his portraits, as do the high forehead, large nose, and cleft chin. Positive identification of a figure from other portraits is notoriously difficult, but other evidence points to Menshikov as the subject here. He would naturally appreciate association with one of history’s greatest military leaders and especially Alexander, his namesake. The scene of Alexander with his friend and counselor Hephaestion would have reminded everyone of Menshikov’s close relationship with Peter the Great. The Russian commander would also have appreciated the reference to the Roman emperor Trajan, whose many victories in battle brought about an auspicious moment in the Roman Empire’s history.[5] Both of the oval scenes on the cuirass show a ruler’s magnanimity, flattering compliments to any leader. Furthermore, Menshikov appreciated dexterity in wood carving: his private study, the Walnut Room, featured marquetry, and he installed a turnery for working wood and other materials in his Saint Petersburg palace. The first in the city made of stone, that building was richly decorated. We also know that a sculptor, probably Swiss, named Franz Ludwig Ziegler, or Zingler, residing in Russia, made a trip at Menshikov’s expense to western Europe and returned to Russia in 1703 accompanied by three sculptors, two Austrian and one German. There is no documentary evidence that any of them or Ziegler carved the bust, but they were available for the task. It has been proposed that the bust dates from that time, since after 1703 it probably would have incorporated the insignia of the Order of Saint Andrew, Russia’s highest military honor, which Menshikov received that year. His ennoblement in 1702 in the wake of his military victory over the Swedish army at Schlüsselburg may have been the occasion for commissioning the bust. Although our evidence is circumstantial, a strong case is made for identifying this striking image with one of Russia’s great heroes.

[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 51, pp. 154–55.]

Footnotes

1. Wolfram Koeppe and Marina Nudel. "An Unsuspected Bust of Alexander Menshikov." Metropolitan Museum Journal 35 (2000), pp. 161-77.

2. J. Thomas Quick, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Madison, Wisconsin, identified the wood as pinus sylvestris on March 17, 1996. Carbon dating of the wood was conducted by Dr. George Bonani, Institute of Particle Physics, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule, Zurich, on March 28, 1996; he concluded that the tree that was the source of the wood was felled no later than 1667. As it was common practice to cure wood for long periods of time before working it, the pieces from which this bust was made could certainly have been seasoned in a shop for thirty-five years before they were put to use, about 1703.

3. See Nikolai Ivanovich Pavlenko. Aleksandr Danilovich Menshikov. Moscow, 1981 and the other biographical studies cited in Koeppe and Nudel 2000, p. 176, nn. 19, 20, 25.

4. Koeppe and Nudel 2000, figs. 6 – 9, 11 – 13.

5. For a full discussion of the classical references, see ibid., pp. 170 – 73.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.