Does your life ever feel out of control? For Yvette Weaver, a horticulturist, gardens offer respite, and her work in them continues a family legacy of connection to nature. She previously worked in the gardens at The Met Cloisters, where the design and plantings are directly inspired by the collection of medieval art on display. Discover the morning stillness with her—before visitors arrive—when the garden feeds her senses and helps her take stock of the world. Tune in to hear how gardens sustain her sense of purpose and belonging as a Black woman, and how museums can become more welcoming spaces for everyone.

Listen to the podcast

Seeding Change

Subscribe to Frame of Mind wherever you listen to podcasts:

Listen on Apple Podcasts Listen on Spotify Listen on Amazon Music

Transcript

Yvette Weaver:

There’s hundreds of different plants that are in the garden. They’re all their own being and need their own care. It’s all in the same space, but we’re still kind of like giving everyone their place to shine. It’s that diversity. You need that.

Barron B. Bass:

Welcome to Frame of Mind, a podcast from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, about how art connects with wellness in our everyday lives. Yvette Weaver is a horticulturist. Until recently, she worked at the Cloisters, The Met’s upper Manhattan location dedicated to medieval art. During the middle ages, cloisters in Europe had gardens that were designed to support spiritual reflection and to grow ingredients for medicine and healing.

This inspiration is clear at The Met Cloisters, especially in the tranquil gardens that Yvette cared for. The gardens are an oasis for Yvette, and she wants everyone to feel welcomed in these spaces, even though she hasn’t always felt welcomed herself. Her story starts in a place of peace and quiet—a morning among the plants and flowers at the Cloisters.

Yvette Weaver:

So silence and stillness have always been a part of my existence. A really wonderful part of this job is that we have two hours in the morning before the public comes in. So, you know, this morning while I was sweeping, it’s just, it’s like we have the gardens to ourselves. And it’s just quiet and so it’s a nice way to start the day every day.

It’s like we’re in partnership, the plants and I, are in partnership of creating a space for other people to be able to come in and just have that meditative space.

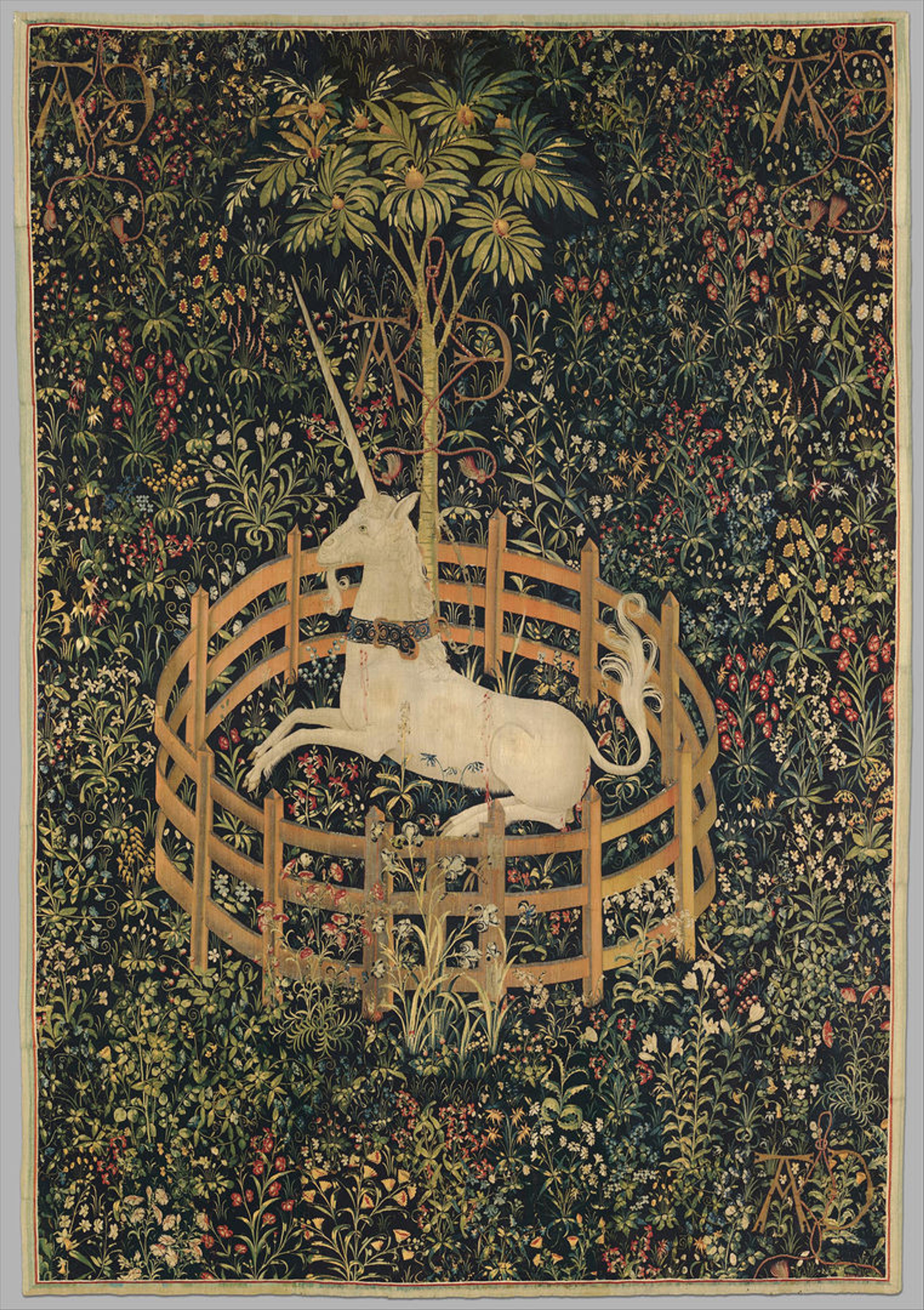

Our plants are very specific to the artwork. And so we’re taking what you would find in the unicorn tapestries. Specifically, that very famous unicorn picture where it’s the single unicorn who’s encaged, and over that unicorn are many other plants being depicted. The irises are definitely very prominent in the unicorn tapestry, shrubs like the Michaelmas Daisy, Campanulas, and then the Dianthus.

The Unicorn Rests in a Garden (from the Unicorn Tapestries), 1495–1505. Made in Paris, France (cartoon); Made in Southern Netherlands (woven). 144 7/8 x 99 in. (368 x 251.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1937 (37.80.6)

Right now we have a rowan tree, which you’ll see growing in the tapestries. It just has a very beautiful presence in the garden right now. In the early spring, mid-spring, it was just phenomenal. I kept kind of running back and forth between that garden and looking at the unicorn tapestries and like going back outside; you really do feel like you’re standing in the middle of the unicorn tapestry. It’s pretty amazing.

I do feel like this is a form of art for me, or creating art.

My earliest memory of gardening and really wanting to do something outside was I think I was about four or five years old. That’s when I first decided to weed my dad’s garden, which had already been planted. But, I thought I was being helpful. As I learn more about my family, I realize just how deep those roots go into plants.

My mother’s side of the family is Hungarian and German Jewish and on my father’s side, his family is black American from Georgia. The grands in my family—my grandparents, my great aunt—that has always been part of who they were and what they passed down to me. I feel like it’s a part of me before I was me.

So once I graduated, I became a program coordinator for an organization that did a lot of trail work. And so I was outdoors regularly, building trails. And especially when I was young and I, you know, in my twenties probably still looked like I was a 15-year-old. So I think people were very surprised to see me show up, to see this little skinny woman coming through and using big weed whackers.

I definitely got a lot of pushback and I definitely got a lot of comments and, you know, “Are you really capable of hiking up that mountain and using that?” I’ve been taught by my family how to find that inner strength to be able to keep pushing forward. This is what I feel passionate about and love doing. So there’s nothing that’s going to stop that. So that kind of spring–boarded me into New York City’s public gardens.

Birds, sparrows. There are a lot of nesting birds through the covered walkway areas and in the roof. I’m looking out onto this beautiful large oak right now. You really hear the wind moving through the trees here, moving through the gardens. Just brings such peace and like energy to the body as well.

I think the most important thing really is that slowing down, that paying attention and being really mindful, looking at the shape of a flower and how these different little curls are just really amazing to look at. You know, when I say that working in public gardens is really important to me, this is one of the reasons why. The second people walk into a garden space, their whole demeanor, just like shifts and changes. And I think gardening now is being reminded of that. Like, I’m not in control, at all. Nature’s in control. Period.

Photograph of the Bonnefont Herb Garden at The Met Cloisters. Photo: John M. Hall

We think we have a beautiful garden going and everything’s wonderful and great and a big storm can come through and just wipe it all out in the middle of a season and you’re starting over again. You have to learn to let go.

Unfortunately I think, even here, people say, “Well, like look at her, what does she know?” It’s really fascinating to me because I’m physically there in front of someone, actually doing the act of gardening and I’m asked, “Oh, who does this? Who maintains this?” Even when they’re seeing me doing it, they like can’t register that it’s happening.

Fortunately, that doesn’t happen a lot, but there’s definitely times that I hit some resistance from visitors and I think no matter where I’ve worked, that’s something that’s happened. You know, I also don’t want to like dwell on I’m a black woman working in the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Cloisters. I don’t want to dwell on that being the thing, because I love gardening. I love horticulture. I love my job. But there is an element that I am a black woman working in these gardens.

My relationship to nature is very, I’m very in tune with that relationship. But what I do witness and what I do see is that it’s really something that’s innate in all of us. We all belong in these spaces.

I hope that it does give people of color, who are coming into the gardens and sitting down and relaxing and reading a book, that they can feel like, “Oh, okay, well there’s somebody out here working who looks like me and I can like relax a little bit.” And especially for the students who are black and brown, I was like a rockstar to them.

So, I mean, I would just have these like precious little six-year-olds running up to me. These little black girls, who would just pick a, you know, find a little dandelion and run over to me and be like, “Look, I’m gardening too.”

The gardens have always just been just a place like every morning where I’ve just gone and processed what’s happening in my life. You know, the good, the bad. This past year has just been incredibly heavy. Especially in the beginning of it when we really were in the lockdown. And I think hearing the sirens going, I mean, I feel like there was a two-week period where we just almost heard sirens for twenty four hours straight. It was really, very intense.

And people losing loved ones. And then on top of that, George Floyd’s death. The death of so many others. I hope that white people are able to hear us. To hear, you know, what it is to walk in the world for us every day and I’m really grateful for the slow down, to be able to slow down, being able to process that all.

I think that there’s something really calming and meditative in the work. Just being able to cry if I needed to. I feel, for myself personally, there’s like an energy exchange between the trees that are growing, and the grass, and the plants. And then myself. I really know those plants up there and they really, they do know me. And you know, there may be a little tendril that reaches out and brushes my cheek, like it’s okay. I’m able to let go and let that soil, let that tree kind of take what I need to release.

Barron B. Bass:

This has been Frame of Mind, an art and wellness podcast from The Met. To find out more about Yvette and the artworks mentioned in this episode, please visit the Met’s website at www.metmuseum.org/frameofmind, where you’ll find bonus articles, features, resources, and videos on the endless connection between art and wellness.

Frame of Mind is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Goat Rodeo. At The Met: Head of Content Sofie Andersen, Executive Producer Nina Diamond, Associate Producer Bryan Martin, and Production Coordinators Harrison Furey and Lela Jenkins. At Goat Rodeo: Rebecca Seidel is Lead Producer. Megan Nadolski is Executive Producer. Production Assistance from Char Dreyer, Isabelle Kerby-McGowan, Cara Shillenn, and Max Johnston.

Senior producer is Ian Enright. Story Editing from Morgan Springer. Series Illustration by Sophie Schultz. I’m your host Barron B. Bass. A special thanks to our guest on this episode, Yvette Weaver.

This podcast is made possible by Bloomberg Philanthropies and Dasha Zhukova Niarchos.

If you liked this episode, please leave us a rating or review and share it with your friends.

Next time on Frame of Mind…

Lakshmee Lachhman-Persad:

Artists are able to create from their perspective, with their disability. It’s not overcoming their disabilities.