Three Waka Poems

This waka kaishi—a sheet recording compositions from a poetry gathering—features three poems by the monk-poet-calligrapher Tonna. He recited these at a 1367 gathering at Nii-Tamatsushima Shrine, in Kyoto, hosted by the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiakira and attended by the day’s most prominent waka poets. Although the characters appear casually arranged, suggesting spontaneity, their plump shapes reflect Tonna’s study of the Sesonji school, established by the master calligrapher Fujiwara no Yukinari (972–1027). The final poem reads:

目にむえぬ 神のあはれむ 道をなを

わきてぞまもる 玉津しま姫

The goddess of Tamatsushima

maintains a pathway

from the heavens

so gods can manifest themselves

even if invisible to the eye.

—Trans. John T. Carpenter

目にむえぬ 神のあはれむ 道をなを

わきてぞまもる 玉津しま姫

The goddess of Tamatsushima

maintains a pathway

from the heavens

so gods can manifest themselves

even if invisible to the eye.

—Trans. John T. Carpenter

Artwork Details

- 頓阿法師筆 三首和歌懐紙

- Title:Three Waka Poems

- Artist:Monk Tonna (Ton’a) (Japanese, 1289–1372)

- Period:Nanbokuchō (1336–92) period

- Date:ca. 1368–69

- Culture:Japan

- Medium:Poetry sheet (waka kaishi) mounted as a hanging scroll; ink on paper

- Dimensions:Image: 11 3/4 × 18 1/8 in. (29.8 × 46 cm)

Overall with mounting: 46 1/8 × 22 15/16 in. (117.2 × 58.3 cm) - Classification:Calligraphy

- Credit Line:Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Gift of Mary and Cheney Cowles, 2022

- Object Number:2022.432.5

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

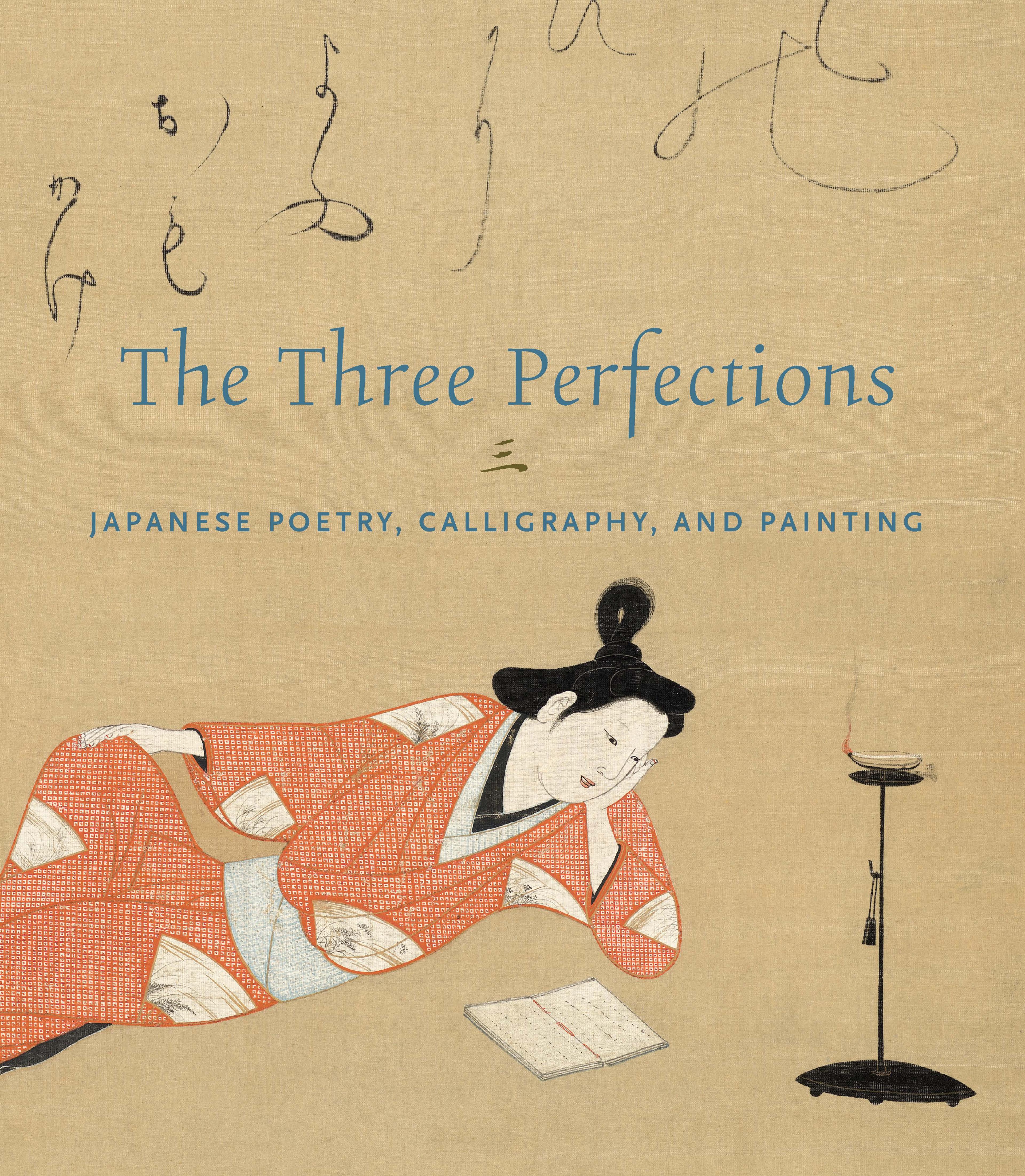

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.