Fig. 1. Panel carved in the "beveled style" with remains of later polychromy, last quarter 10th century. Egypt. Islamic. Wood (black pine); carved; H. 18 1/2, W. 27, D. 3 in. (47 x 68.6 x 7.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1932 (32.102.1, 2)

«As conservators and conservation scientists, we are responsible for the technical examination of works of art here at the Met. When Matt Saba, an Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Islamic Art, asked us to work with him to investigate the original function and decoration of a tenth-century relief panel (fig.1), we were thrilled to undertake the necessary detective work. As a result of our investigation, we learned that the panel was once part of an architectural element, but also that the partially surviving polychrome decoration was applied after the panel was removed from its original context and repurposed.»

Surviving in two pieces, the panel itself is clearly a fragment, as evidenced by the cut through the ornament on the right side. The scale, orientation, and repetitive undulating pattern together suggest that it originally belonged to an architectural element, probably a wall frieze. The manner in which the left side was finished suggests that the panel was an end section of the frieze, but close inspection reveals that some of the original ornament has been chiseled away to create a flat background (fig.2).

Fig. 2. The continuation of the ornament on the left-hand side of the panel was chiseled away

Only on the top and bottom do we have original edges. Looking closely at the end grains, we noted identical growth rings on both pieces, which shows that they are two halves of the same board (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Right edge of the panel, showing that both sections have identical growth rings

The gap between them was presumably the pith and juvenile wood that form the center of a tree trunk, which have a tendency to crack along the grain and probably caused the carved panel to split in half. Subsequently the damaged areas were removed, resulting in the gap we now see. Based on these observations, we can say that the panel was cut from the center of the tree and estimate that the original frieze was about eighteen and a half inches high and three inches thick.

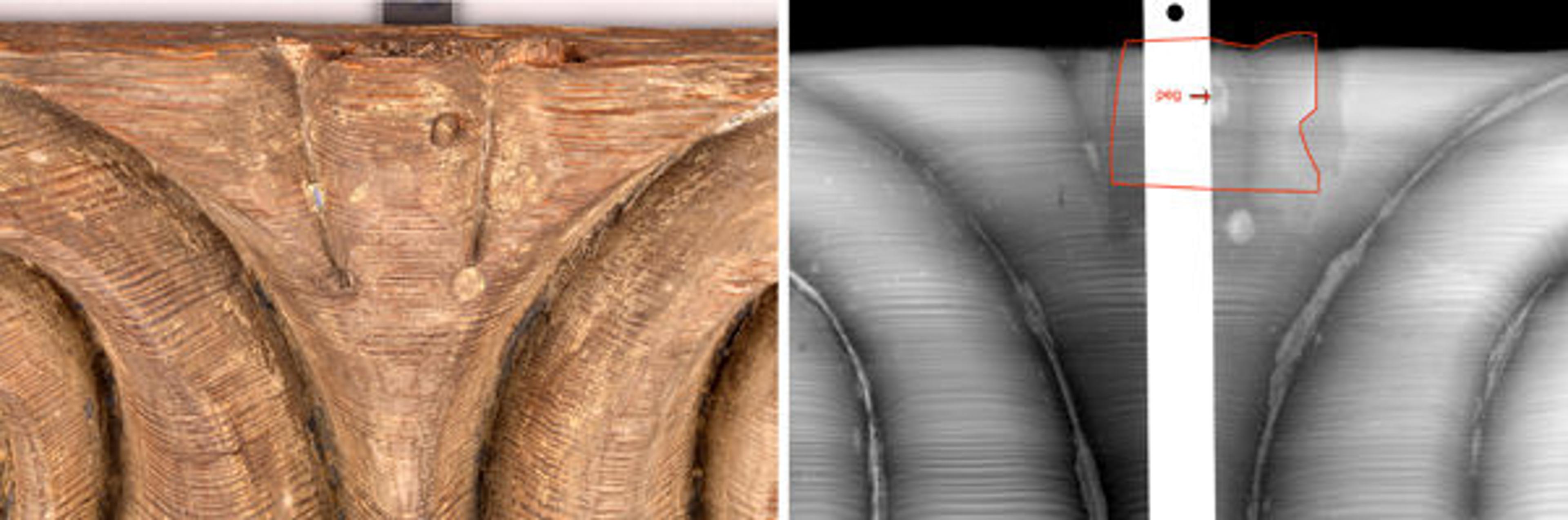

The examination also revealed evidence of a total of four mortise-and-tenon joints along the top and the bottom of the panel, which reflect the method used to attach it to a wooden structure. Each tenon was secured with a peg, and examination of the surfaces under ultraviolet light—a technique used to distinguish between different materials based on their fluorescence or lack thereof—confirms that no adhesive was used for the joinery. As seen in the X-ray radiographs, the mortises are nearly identical in size and all were cut out with hand tools in the same rough manner. The upper right-hand joint is the only one still containing a tenon, the upper part of which has been sawn off along the edge of the panel (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Left: Upper right-hand mortise-and-tenon joint. Right: Radiograph of the joint, showing a red line that marks the outline of the tenon. The peg and joint are partially obscured by the high radiopacity of the metal mount.

It is interesting that the carving continues onto the exposed edge of the tenon, which was presumably added when the panel was removed from its original setting and presented as an independent work. Also noteworthy is that the mortises were randomly placed; it is likely that they were cut before the ornament, which was carved so deeply that the carving intersects with three of the four mortise cavities, and as a result, the tenons, when inserted, were partially exposed.

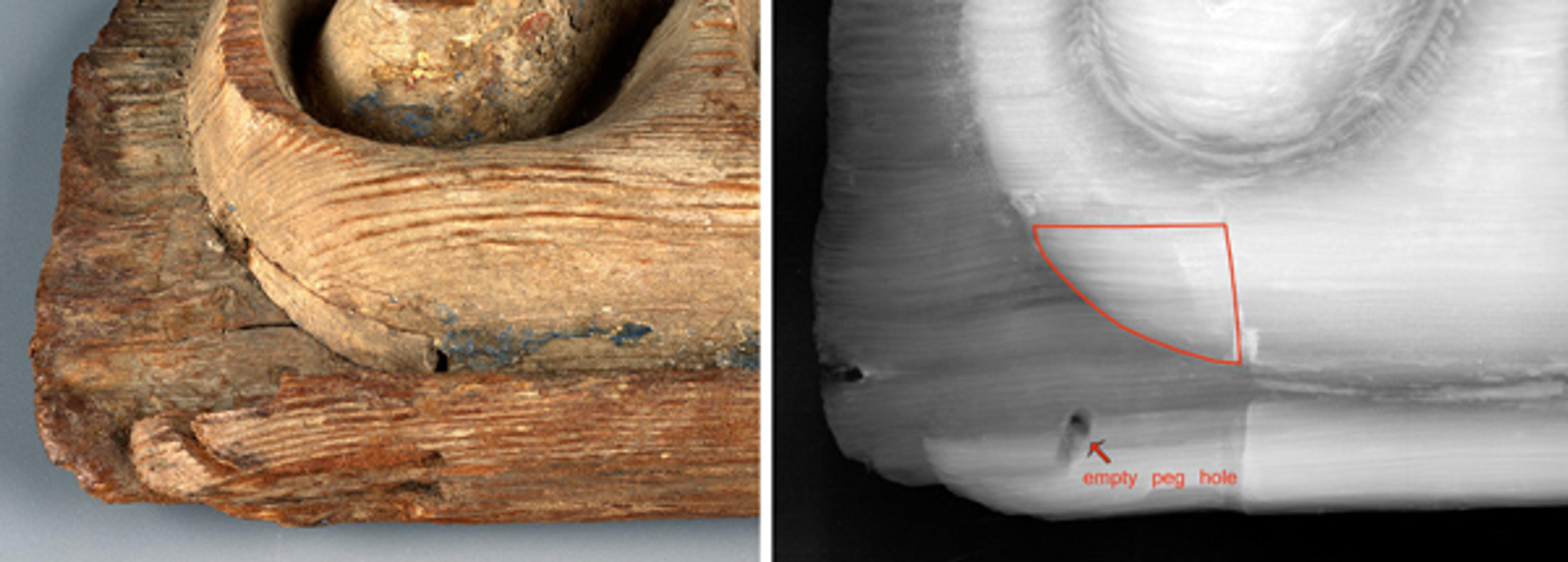

Later, when the ornament was chiseled away from the left side of the panel, both nearby tenons and part of the mortises were removed. A piece of wood now in the mortise on the lower left appears to be a later addition intended to disguise the presence of the mortise. We see in the radiograph that it fits more tightly than the one surviving original tenon and the direction of its grain is horizontal rather than vertical (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Left: Lower left-hand mortise-and-tenon joint with later wood fill. Right: radiograph of the joint

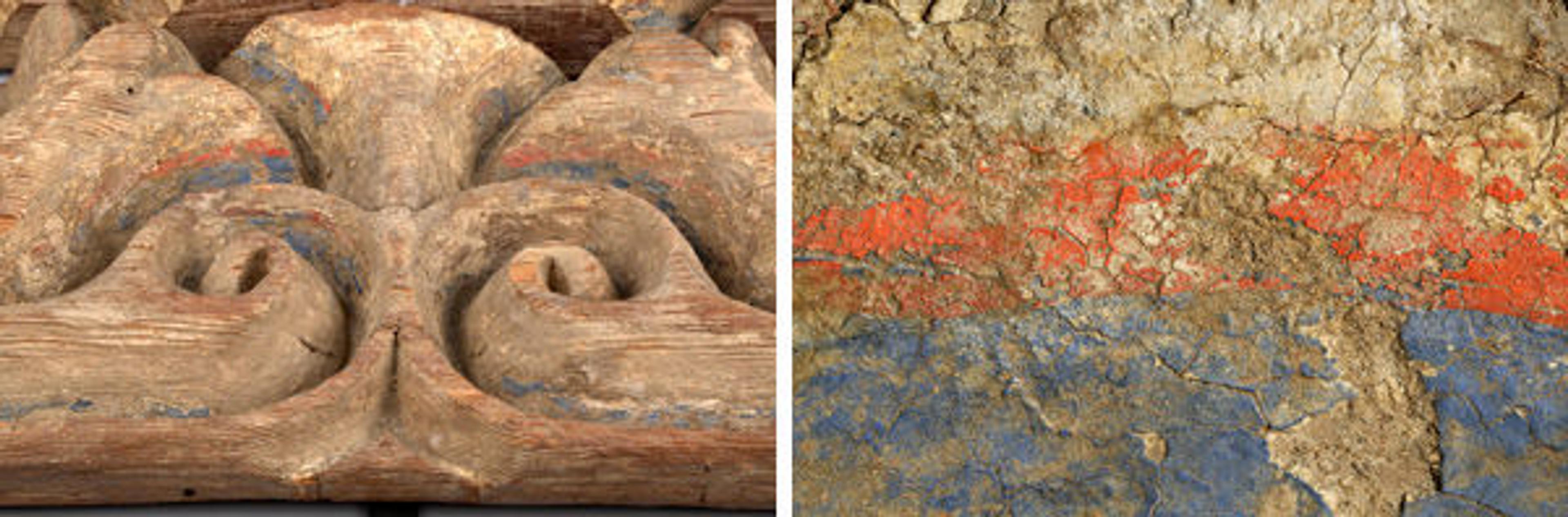

Another aspect of our examination was the polychrome decoration. With the unaided eye, patches of blue paint partially covered by later surface layers can be seen in the recessed areas, bordered by a narrow red band running about halfway up along the beveled edges of the carved ornament (fig. 6). Only with a microscope can we see traces of gold leaf above the red border (fig. 7).

Left: Fig. 6. Remnants of polychrome decoration. Right: Fig. 7. Detail of polychromy showing the red band running between the blue painted areas and the gilding

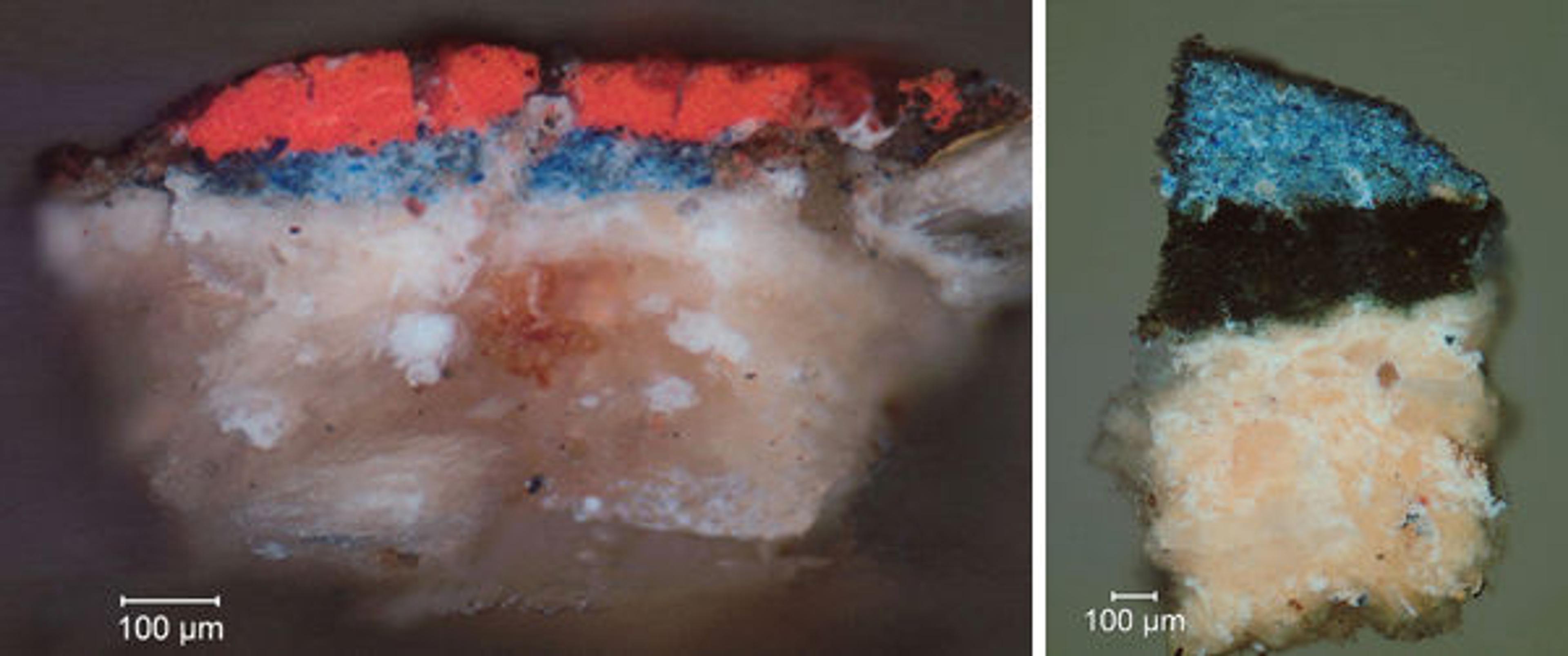

In order to reveal the stratification and composition of the individual layers, samples were prepared as cross sections for examination under the microscope (figs. 8–9). A whitish ground layer composed of calcium sulfate hemihydrate with some gypsum was applied over the entire surface before the application of the gold leaf, which is present only on the upper half of the beveled edges. A dark blue paint containing indigo followed by a brighter blue paint pigmented with natural ultramarine were applied on the bottom half, in some areas overlaying the gilding. The red band, containing vermillion, was painted last. Analysis of the binder indicated protein derived from egg and collagen. The identified materials have been traditionally used for painted surfaces and therefore don't provide clues for dating of the decoration. How the pigments and binders were analyzed and the results interpreted will be the subject of a follow-up blog post.

Left: Fig. 8. Cross section showing the sequence of application: whitish ground, gold leaf (present on right side), blue paint, and red paint. Right: Fig. 9. Cross section of a sample taken from the crevice in the carved ornament, showing the sequence of application: whitish ground, dark blue indigo underpaint, and bright blue ultramarine paint

Given that the whitish ground and both blue paint layers are present on the exposed edge of the later fill in the lower left-hand mortise as well as at the bottom of the crevice on the lower right where the tenon was located, we can conclude that this surface decoration is not original, and that it was applied after the panel was removed from its architectural setting. The question of whether or not this scheme reflects the original decoration remains for the future (fig. 10). Ongoing research on early woodwork from Egypt and elsewhere in the Islamic world may prove helpful in this regard.

Fig. 10. Hypothetical reconstruction of the painted and gilded decoration on the panel. Since traces of the gilding were only found on the upper half of the beveled edge of the carved ornament, the gilding on the top surface is speculative. Digital reconstruction by Chris Heins, associate imaging specialist in the Met's Photograph Studio

Related Link

RumiNations: "Asking Questions of a Tenth-Century Carved Wood Panel" (May 12, 2015)