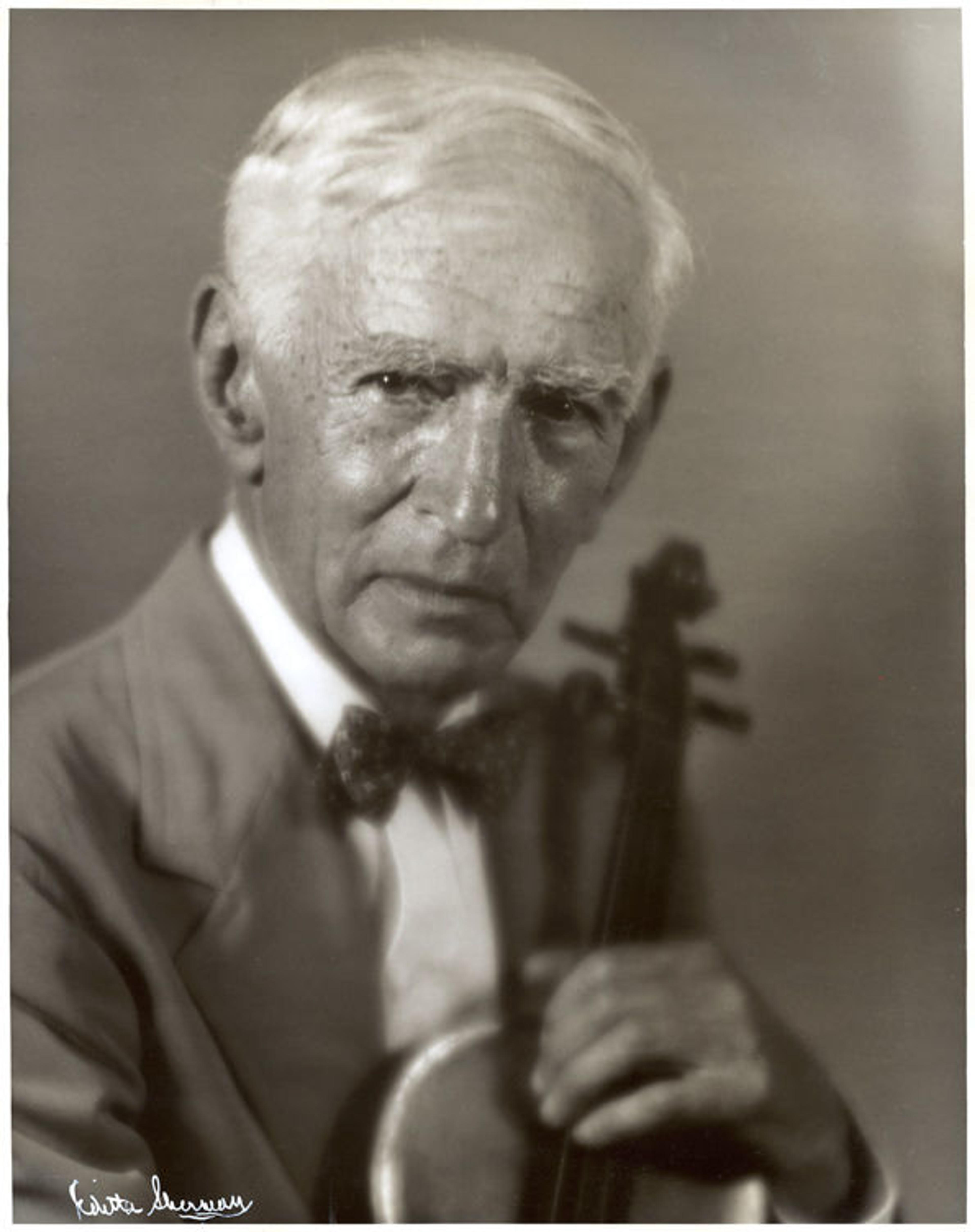

David Mannes. Photograph by Editta Sherman

«David Mannes (1866–1969) was a violinist, famed conductor, and one of the most important music educators in the United States, best known for the Manhattan music school he founded in 1916 which today is Mannes College The New School of Music. Though never a Museum employee, Mannes began the distinguished history of musical performances at the Met. He conducted at the Museum for more than forty years, and for thirty years led regular free concerts that The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin described in 1949 as having "America's largest indoor audiences." Particularly during the 1930s, when the Museum had no curator knowledgeable about instruments, Mannes also advised on the acquisition of instruments and their care.»

Mannes grew up in New York City, the son of immigrants. He collected and sold discarded bottles to pay for violin lessons from, among others, the son of a freed slave in Harlem, and by the age of fourteen was playing the violin to support himself, everywhere from skating rinks to bordellos. Mannes studied with the concertmaster of the [New York] Philharmonic Orchestra, traveled to Berlin for further study, and by 1891 was back in New York as a violinist (later concertmaster) with the New York Symphony Orchestra, then conducted by Walter Damrosch. In 1898 he married Damrosch's sister, Clara, a fine pianist, and the two became fixtures of New York's musical society. Mannes never forgot his poor immigrant roots, however, and later in life, while conducting regular concerts at the Museum, he also founded music schools in Harlem and the Lower East Side.

Mannes continued to play the violin for most of his life, but his lasting fame came as a conductor. Initially he led concerts at the Museum for the invitation-only receptions that took place several times a year; the first occasion may have been on November 15, 1905, when he led the New York Symphony Orchestra at a reception for eight thousand attendees honoring the Museum's new director, Sir Purdon Clarke. Over the next several years, Mannes and the New York Symphony Orchestra functioned almost as the in-house orchestra for all of the Museum's non-public parties held by the director and trustees. The programs he chose were a mix of traditional repertoire, including symphonic works by Mendelsshohn, Beethoven, Schubert; works by contemporary composers like Saint-Saëns, Humperdinck, and Dvořák; Strauss waltzes; as well as the wildly popular Wagner.

In 1911, after several years of these receptions, Mannes wrote to John Pierpont Morgan, chairman of the Board of Trustees, advocating the installation of a pipe organ in the brand new Great Hall, for the purpose of holding regular concerts there. (Mannes had already tried conducting in the Great Hall, which he said had "wonderful acoustic properties.") By 1914, the Museum had obtained an estimate of $10,000 for the Great Hall organ. Though the organ was not installed until the early 1950s (and didn't last long in the space), Mannes was successful in persuading the Museum to move his concerts to the Great Hall.

David Mannes conducting on the North Balcony of the Great Hall

The United States' entry into World War I in November 1917 brought the Museum's building plans, including the pipe organ installation, to a halt, but was the catalyst for the first of the Museum's thirty years of free public concerts. As the Museum Bulletin reported:

. . . [T]wo orchestral concerts will be given in the Fifth Avenue hall of the building on Saturday evenings, February 9 and 16 [1918], from eight to ten, by an orchestra of fifty-five performers conducted by David Mannes. These concerts are offered by the Museum primarily to soldiers and sailors who are stationed in and near New York, and their friends, but they will be open to the general public without charge. The music will be of the same character as that given at the Museum receptions, and the National Anthem will be played each evening at nine o'clock.

Attendance at the first of these soldiers' concerts was 781; the musicians were recruited by Mannes from the New York Symphony Orchestra (and later, after its merger with the Philharmonic Society of New York in 1928, from the New York Philharmonic) and were paid union rates. Frances Morris— assistant curator, and the first professional woman employee at the Museum—who had been responsible for the Musical Instruments collection since 1896, delivered a lecture illustrated with instruments from the collection, as she did for each Mannes concert through 1924 (others handled the lecture-demonstrations beginning in 1925). John D. Rockefeller and daughter Abby attended one of the 1918 concerts, and offered to pay for more concerts the following year. Thus, in 1919, there were four instead of two:

. . . [C]oncerts by an orchestra of fifty-two performers, selected from the best orchestras of the city, under the direction of David Mannes, are to be given in the Fifth Avenue hall of the Museum on the four Saturday evenings of this month . . . free to the public without tickets of admission, and the entire Museum, also, will be open to visitors on these evenings.

Audience in the Great Hall for the February 1, 1933, Mannes concert

The 1919 concerts saw a tenfold increase in attendance from 1918, to over seven thousand visitors for the sixth in the series. Museum President Robert de Forest made a public appeal for more sponsors to underwrite free concerts. He estimated the cost of a single concert at $1,000, or less than fifteen cents per attendee, primarily for heating, lighting, and guards. Funding immediately came for four more concerts in March 1919, and the series settled down to a regular eight per year: four in January, paid for by John D. Rockefeller for twenty years, and four additional ones in March, funded by various donors.

The orchestra continued to consist of fifty to sixty musicians, all recruited by Mannes. The Museum stayed open until 10:45 on concert nights; concerts began at 8:00 and people were free afterwards to visit the galleries or eat dinner at the Museum Restaurant. Concertgoers stood or sat on the floor, stairs, railings, and pedestals.

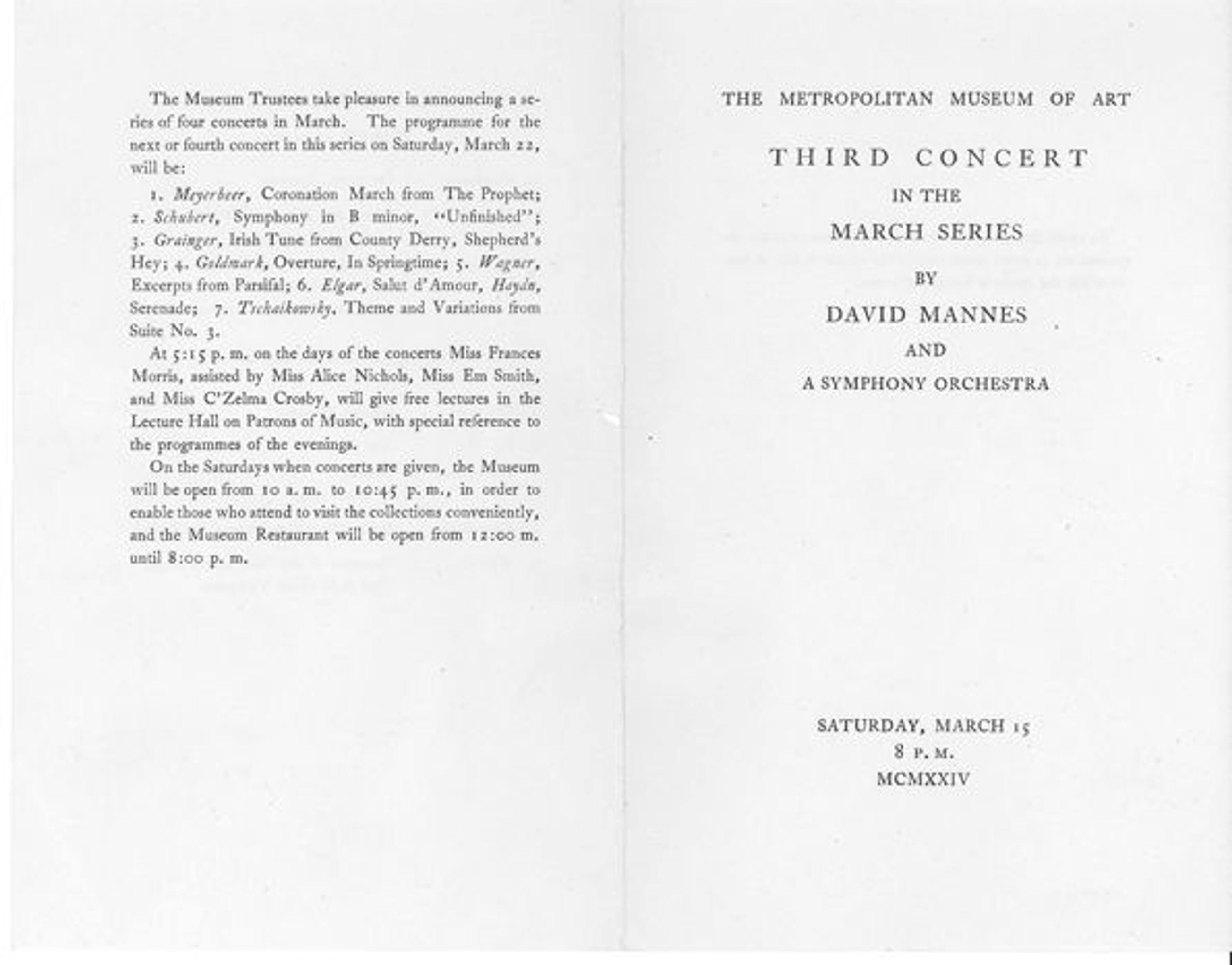

Program for the March 15, 1924, concert by "David Mannes and a Symphony Orchestra" announcing Frances Morris's preceding lecture-demonstration

Each concert was preceded by a lecture on a musical topic generally related to the concert program and demonstrations on the Museum's instrument collection, which were "frequently brought" to the lectures preceding the concerts for "minute inspection." Morris's notes and drafts for the lecture preceding the March 15, 1924, concert survive and show the sophisticated level of musicianship of these lectures. For this typical lecture, Morris was assisted by three musicians who played bassoon, violin, cello, and piano, to pick out themes from the pieces being performed. Miss Morris described the "restless agitation characteristic of this composer's (Tchaikovsky) music" as shown by the "rhythmic diminution of themes." She spoke of the differences between plucked and bowed strings, subdominant and tonic chords, tremolo playing, and other techniques in the symphony. Then, turning to a piece by seventeenth-century composer Jean-Baptiste Lully, she illustrated her lecture with slides of Louis XIV and his world, and lectured on the development of military music in the time of the Sun King, with emphasis on the development of the oboe.

By 1921, attendance at the pre-concert lectures exceeded two thousand; concert attendance exceeded ten thousand per performance, and eventually averaged fifteen thousand to seventeen thousand people. Concerts were broadcast throughout the Museum beginning in 1938, thanks to a pioneering sound system funded by Thomas Watson. During World War II, the concerts were moved to the Morgan Wing and held on Sunday afternoons to save on heating and lighting costs.

Mannes and his concertmaster often played the Museum's two Stradivarius violins, which were donated in 1934. On March 23, 1935, they made their Museum performance debut in the Bach Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor. Shortly afterwards, Museum Director Winlock sent a rather casual memo to the curator of Decorative Arts: "I have just been talking to Mr. Mannes and we agree that it would be well to have someone play them if we can find anyone who is used to the violin. I understand that there was such a person in the Museum, and I should like you to have him practice on them . . ."

David Mannes continued to conduct at the Museum until his retirement in 1948, by which time he had played for audiences totaling well over one million people. (He came back to the Museum in 1956 for one last concert to celebrate his ninetieth birthday.) His retirement was far from the end of Museum concerts: Starting in 1941, Emanuel Winternitz, first curator of the Department of Musical Instruments, greatly expanded the range and format of musical performances organized by the department. However, Mannes' retirement effectively ended Museum sponsorship of large-scale free symphony concerts that brought aural and visual beauty to hundreds of thousands of people during two world wars and the Great Depression—times when the cost of a concert ticket was out of reach for many, and classical symphonic music was revered as "popular music."

Left: Poster announcing the 1936 Mannes concerts