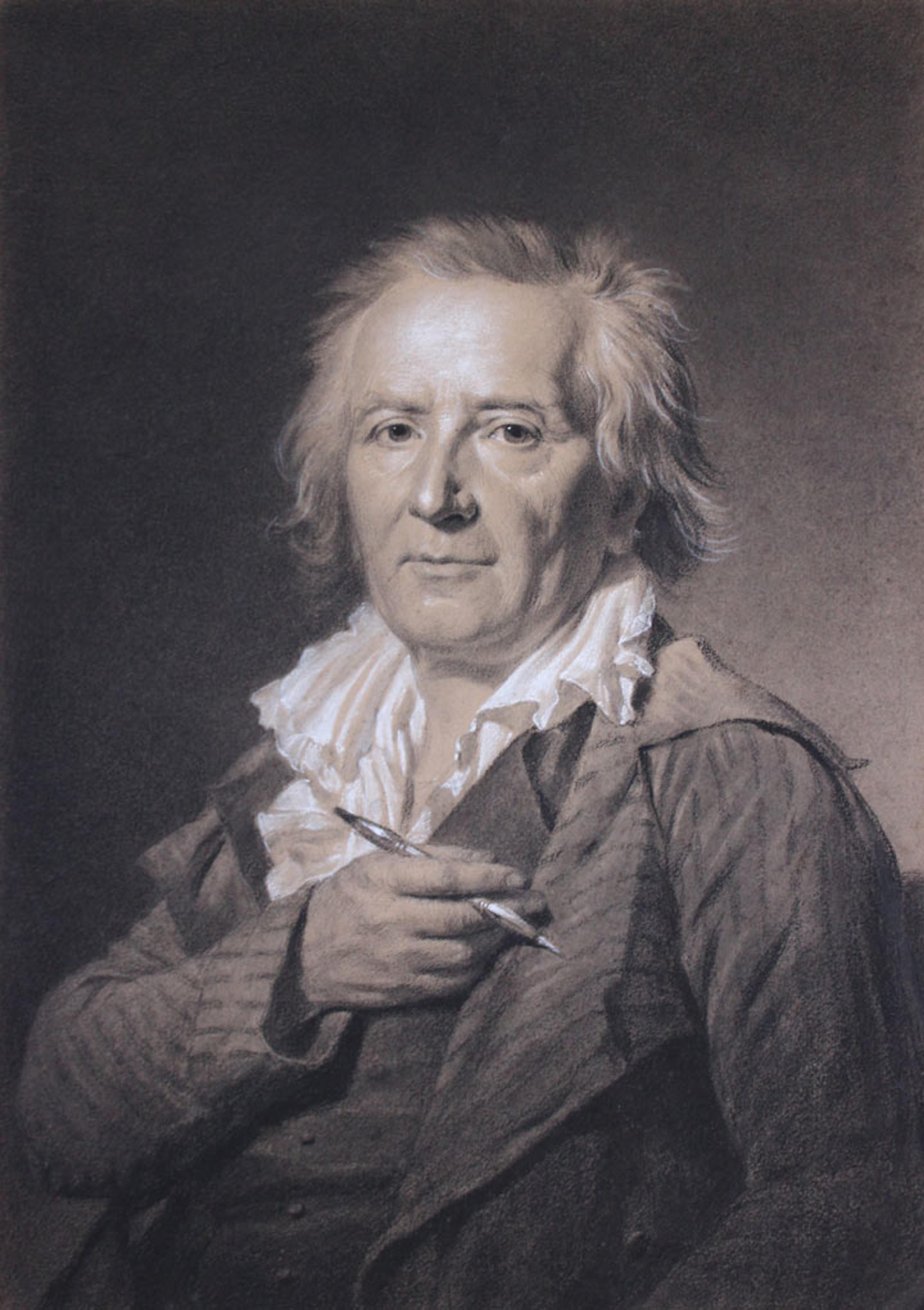

Jacques Antoine Marie Lemoine (French, 1751–1824). Portrait of Jean Honoré Fragonard, 1797. Black chalk, stumped, and heightened with white chalk on beige paper, 12 5/8 x 8 7/8 in. (32 x 22.5 cm). Private collection

«The final work on view in the soon-to-close exhibition Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant—Works from New York Collections stops us in our tracks as we are pulled in by the disarmingly direct gaze of a man who died 210 years ago. He is in his mid-60s, his features are weathered, his hair is gray, but his humanity shines through.»

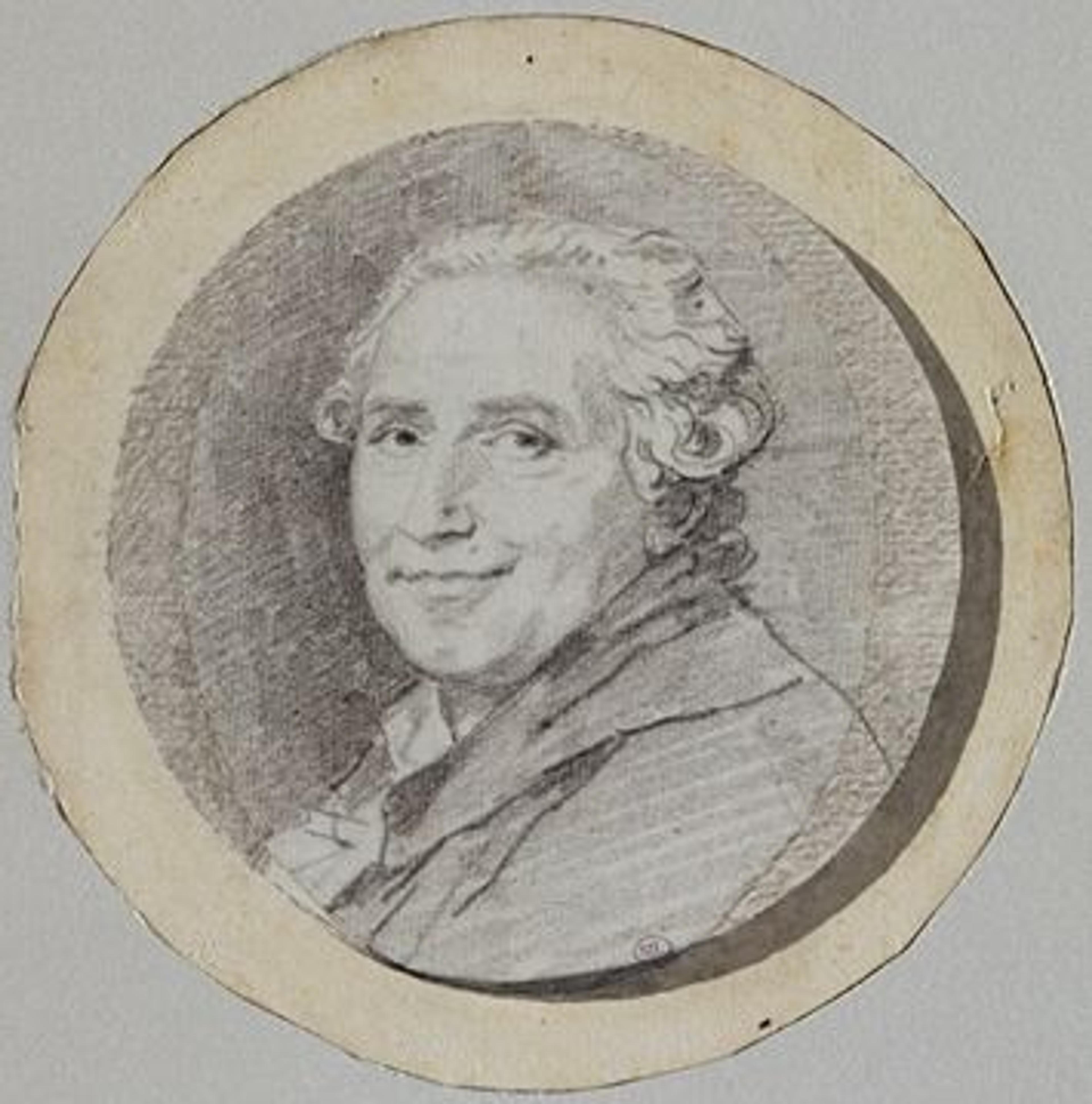

This recently discovered portrait of Jean Honoré Fragonard came to light on the French art market last June and was a late addition to this show thanks to the generosity of its owner, who had possessed the drawing for only a very brief time before agreeing to lend it. Before its discovery, the artist's appearance had previously been known primarily through his own quick sketches, such as the small, circular self-portrait in black chalk shown below.

Left: Jean Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732–1806). Self-Portrait, ca. 1785. Black chalk, 5 x 4 in. (12.6 x 10.1 cm). Musée du Louvre, Paris

Jacques Antoine Marie Lemoine's meticulous and sober portrait, dated 1797, offers insight into one of the least-known periods of Fragonard's life. In 1789 the French Revolution upended all aspects of society, including the arts and art patronage. Artworks connected to the monarchy were systematically destroyed or defaced in the years that followed, and many artists who had been allied closely with the court fled the country. Some of Fragonard's friends, like Hubert Robert and Jacques Louis David, were temporarily imprisoned, although the latter would eventually ride the wave of change with innovative styles that embodied new ideals. Fragonard and his family weathered the immediate aftermath of the revolution in the southern town of Grasse, where both he and his wife had been born.

Returning to the French capital two years later, Fragonard received assistance from David, who helped him secure lodgings in the Louvre and an administrative position in the Muséum Central des Arts (the future Musée du Louvre). The wording of David's recommendation of his friend for the position is often quoted: "[H]e will devote his old age to the preservation of the masterpieces whose number in his youth he helped increase."

It is not known whether Fragonard continued to be active as a painter in this post-revolutionary period; it appears he was primarily occupied with his administrative duties and his family, which included his sister-in-law Marguerite Gérard, a painter, and his son, Alexandre-Evariste, an aspiring artist who trained in David's studio.

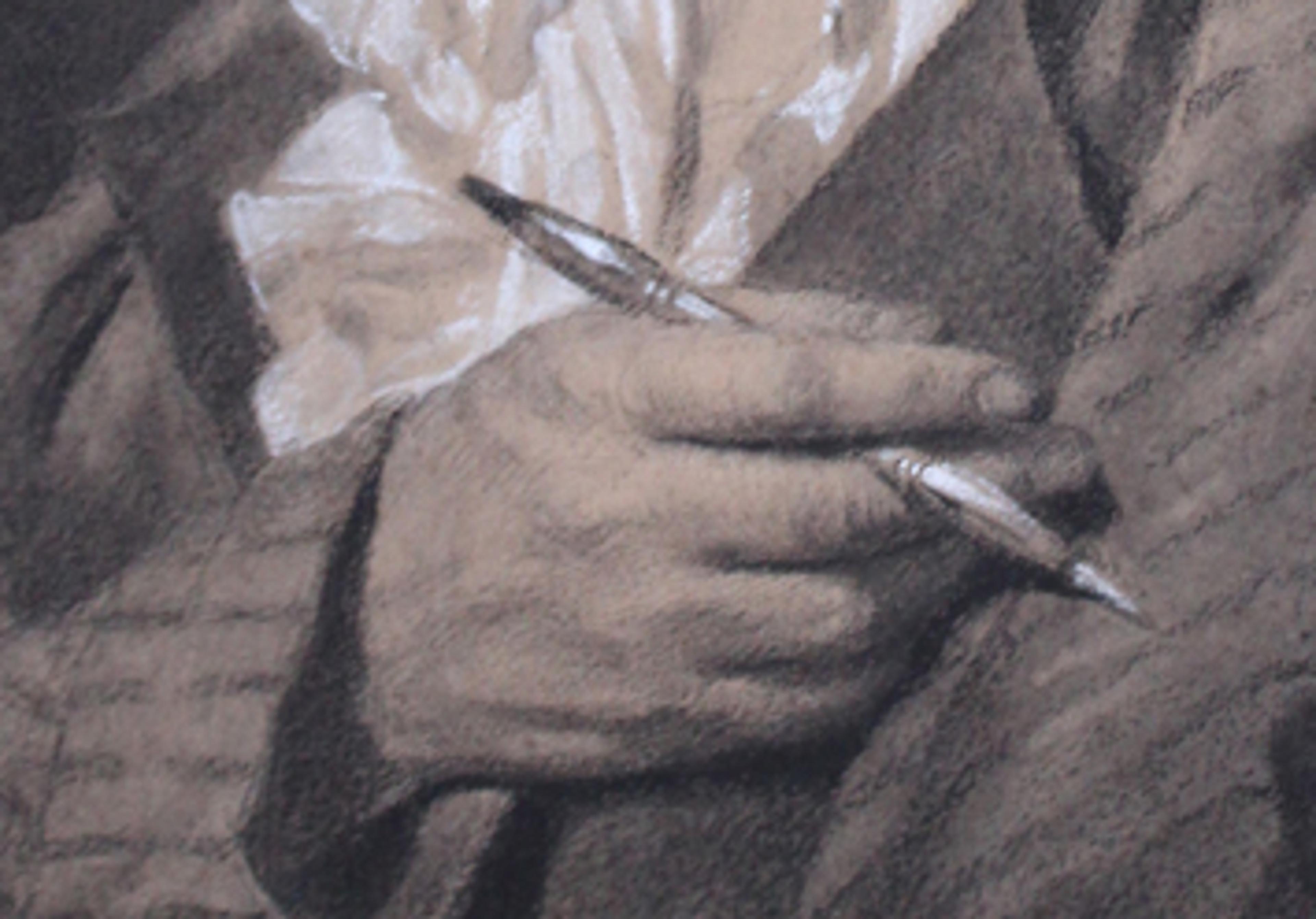

Right: Detail view of Lemoine's portrait of Fragonard showing the artist's porte-crayon

The man portrayed by Lemoine has an intelligent and sympathetic expression. Even though the ancien régime, a period that fed and supported Fragonard's creativity, is no more, the artist clearly hopes that his legacy will survive. In a poignant detail, he is holding to his heart a porte-crayon, a drawing tool for holding chalk. It is not simply his legacy that the portrait commemorates, but, more precisely, his legacy as a draftsman.

Related Links

Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant—Works from New York Collections, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 8, 2017