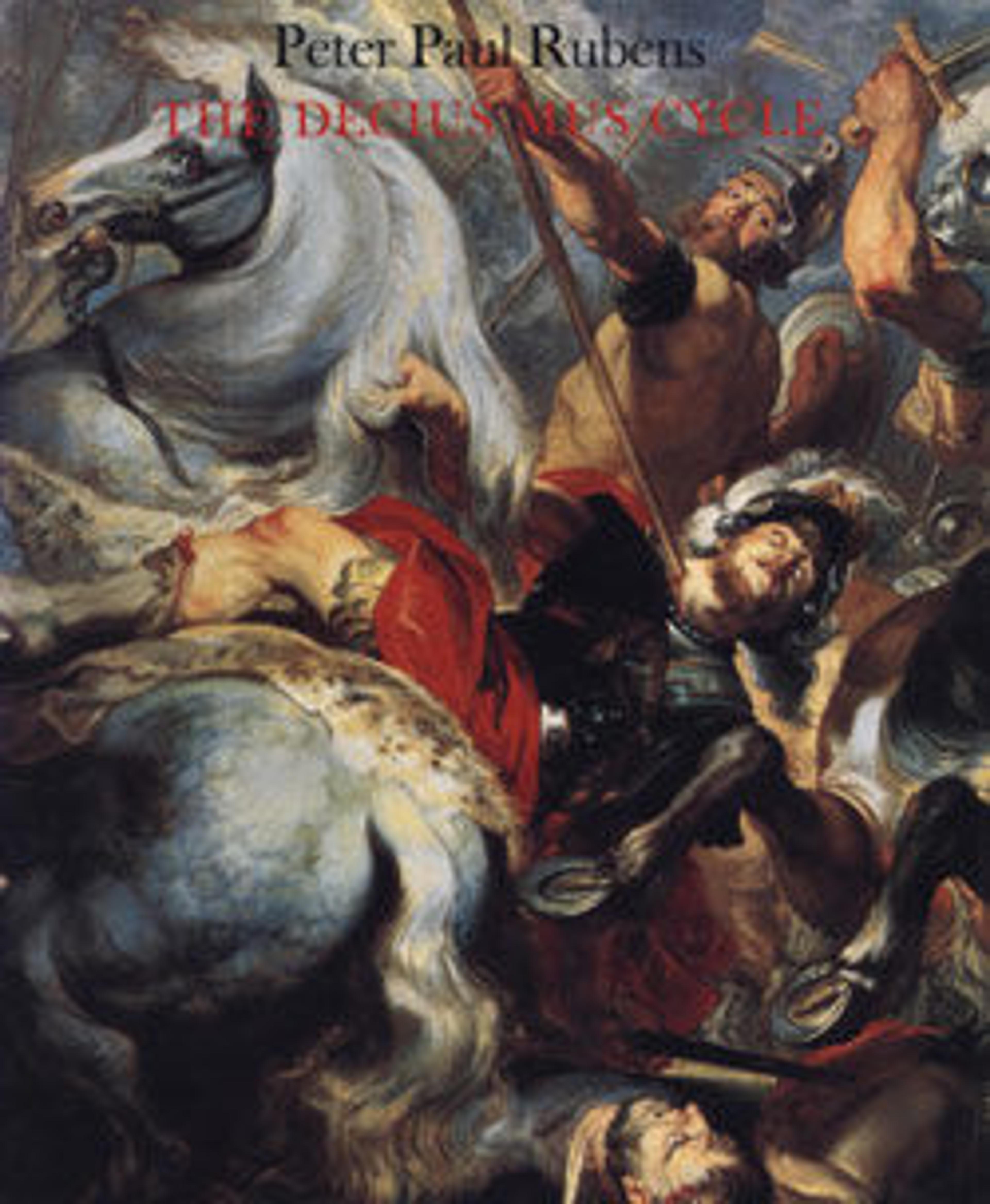

Peter Paul Rubens: The Decius Mus Cycle

The sequence of paintings on the history of the Roman consul Decius Mus, which has been one of the greatest glories of the Liechtenstein collection since its acquisition in 1693, occupies a significant position in the work of Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640). In it the artist uses for the first time the cycle form—that is, the narration of a story through a series of paintings. The development of a sequence of monumental works with abundant imagery and forceful visual impact had a great attraction for Rubens. Again and again he turned his artistic energy to creating cycles, the foremost being the huge paintings celebrating the life of the French queen Maria de' Medici (Louvre, Paris). The Decius Mus cycle is a seminal force in Rubens's career in yet another sense. It is one of the earliest works in which he presented an episode from Roman history; here he made one of his first forays into classical antiquity, a domain that later inspired some of his most important paintings. Rubens himself can be understood only in the context of his extensive classical education. As a member of a circle of humanists around Justus Lipsius, the great master of classical philology and Neostoical philosophy, Rubens was well acquainted with antique thought, literature, and art, regarding as preeminent the authority of these ancient thinkers. The Decius Mus cycle also represents the artist's debut into tapestry design. These larger paintings were not planned as autonomous works of art; instead, the canvases were composed as cartoons, designs that were followed by the weavers as they transformed the master's compositions into tapestries. The Decius Mus cycle was a successful debut for Rubens into the field of tapestry weaving, a time-honored art that was developed in his native Flanders and later spread throughout Europe. Other Flemish artists, especially Jacob Jordaens, followed Rubens's example, thus reaffirming Flanders as the center of tapestry weaving in seventeenth-century Europe.

Documentary evidence indicates that Rubens's preparatory work on the cycle took place between November 1616 and May 1618 and that the commissioners of the series were Genoese noblemen, who have not been identified. Rubens repeatedly visited Genoa during his Italian sojourn, particularly in 1605 and 1606, and he became well acquainted with patrons in that city, serving them with splendid portraits and, later, in 1622, publishing their residences in a volume of engraved views and plans collected during his stays there. It was in Genoa that Raphael's models for the tapestry cycle The Acts of the Apostles (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London) were preserved, and Rubens studied and recorded these cartoons in drawings. Given the personality of Rubens, it seems not unlikely that he would want to prove to Genoa and to the world that he was capable of works that would equal or perhaps even surpass Raphael's cartoons. The concept of the agon—the eagerly entered contest with predecessors or contemporaries—is characteristic of antique art; revived during the Renaissance, it was one of the vital forces that drove Rubens. We continually find him placing himself in competition with the masters of the Renaissance as well as of the classical past. Since he had studied Raphael's cartoons, he might have longed for the opportunity to create an important cartoon series of his own. And by working in oil, rather than the traditional technique of charcoal and colored chalks on paper, he could prove his cartoons to be technically superior to those of his predecessor. Furthermore, as a commission from Genoa, the Decius Mus cycle would be studied by contemporary Italian connoisseurs. Ten years earlier, when he completed the Vallicella altarpiece for the Chiesa Nuova, Rome, Rubens took great pride in challenging the achievements of his Italian colleagues. Italy, the "nutrix of art," profoundly influenced Rubens; reliance on and incorporation of masterpieces from both antiquity and the Renaissance, so evident in the Decius Mus cycle, demonstrate the lessons he had learned from Italy. In his art, however, these antique and Italianate elements were assimilated and transformed in a truly masterly way.

Close examination of the large canvases proves that certain parts should clearly be attributed to Rubens's atelier. Since the painted area is approximately one hundred square yards, this participation is not surprising. The success of Rubens's atelier lay in the subordination of individual talents to the conception of the master artist, and rather than engaging in futile attempts to label workshop areas with the names of individual assistants, it is of much greater import to distinguish accurately between the work of Rubens himself and that of his atelier. Large sections of the canvases are indeed splendid examples of Rubens's own brushwork with its characteristic forcefulness and with the sparkling lights of his modeling. In particular paintings, such as Decius Mus Relating His Dream and The Consecration of Decius Mus, the master's brilliantly vivid style is maintained with a confident ease that no assistant, however gifted, could achieve. Among the four tapestry cycles designed by Rubens, the Decius Mus cycle is the only one in which the artist participated in the execution of the monumental cartoons, a task that stimulated him to a performance of overwhelming grandeur.

The cycle comprises eight cartoons, six with scenes of the narrative actions and two with female personifications and a trophy intended to serve as so-called entre-fenêtres for narrow strips of walls between windows. The first two sets of tapestries for the Genoese clients were woven by the Brussels workshop of Jan Raes the Elder. During the seventeenth century the Decius Mus series was extraordinarily popular, and some twenty further sets were produced from Rubens's designs, but by other manufactories and with varying completeness and border decoration. Since the late nineteenth century parts of a set by Jan Raes woven with gold threads have been in the Liechtenstein collection; these might possibly be identified with one of the two sets, the editiones principes, produced for Genoa. A comparable series is in the Prado, Madrid.

In 1661 six of the present paintings were owned by two Antwerp painters, Gonzales Coques and Jan Baptist van Eyck, together with Jan Carel de Witte. Later they appeared in the estate of van Eyck after his death in 1692. Shortly thereafter, Prince Johann Adam von Liechtenstein acquired the series, supplemented by the two other pictures, which had been in the possession of the Emperor Leopold I, for a total of 11,000 gulden, through the Antwerp art dealer Marcus Forchoudt. The admiration of the Prince for this series is apparent in the exceptionally sumptuous carved cartouches of their frames, which were commissioned by the Prince from the sculptor Giovanni Giuliani in 1706. They were intended to enhance what was considered then, and remains, the greatest pride of the Liechtenstein collection.

Citation

Baumstark, Reinhold, Peter Paul Rubens, and Walter Wachter. 1985. Peter Paul Rubens, The Decius Mus Cycle: The Collections of the Prince of Liechtenstein ; [... Issued in Connection with the Exhibtion “Liechtenstein: The Princely Collections”, Held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from October 26, 1985 to May 1, 1986]. New York, N.Y: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.