“I suppose it is the best thing I have done,“ John Singer Sargent wrote in 1916 to his longtime friend Edward Robinson, Director of The Metropolitan Museum, offering to sell his portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau for what was, at the time, a very modest price.[1]

Despite living most of his life abroad, Sargent considered himself American and wished for his most significant work to be displayed permanently in America‘s preeminent museum. Although many years had passed since its scandalous debut, Sargent had one stipulation, “By the way, I should prefer, on account of the row I had with the lady years ago, that the picture should not be called by her name.“ Robinson accommodated Sargent and the painting was called Portrait of Madame X.[2]

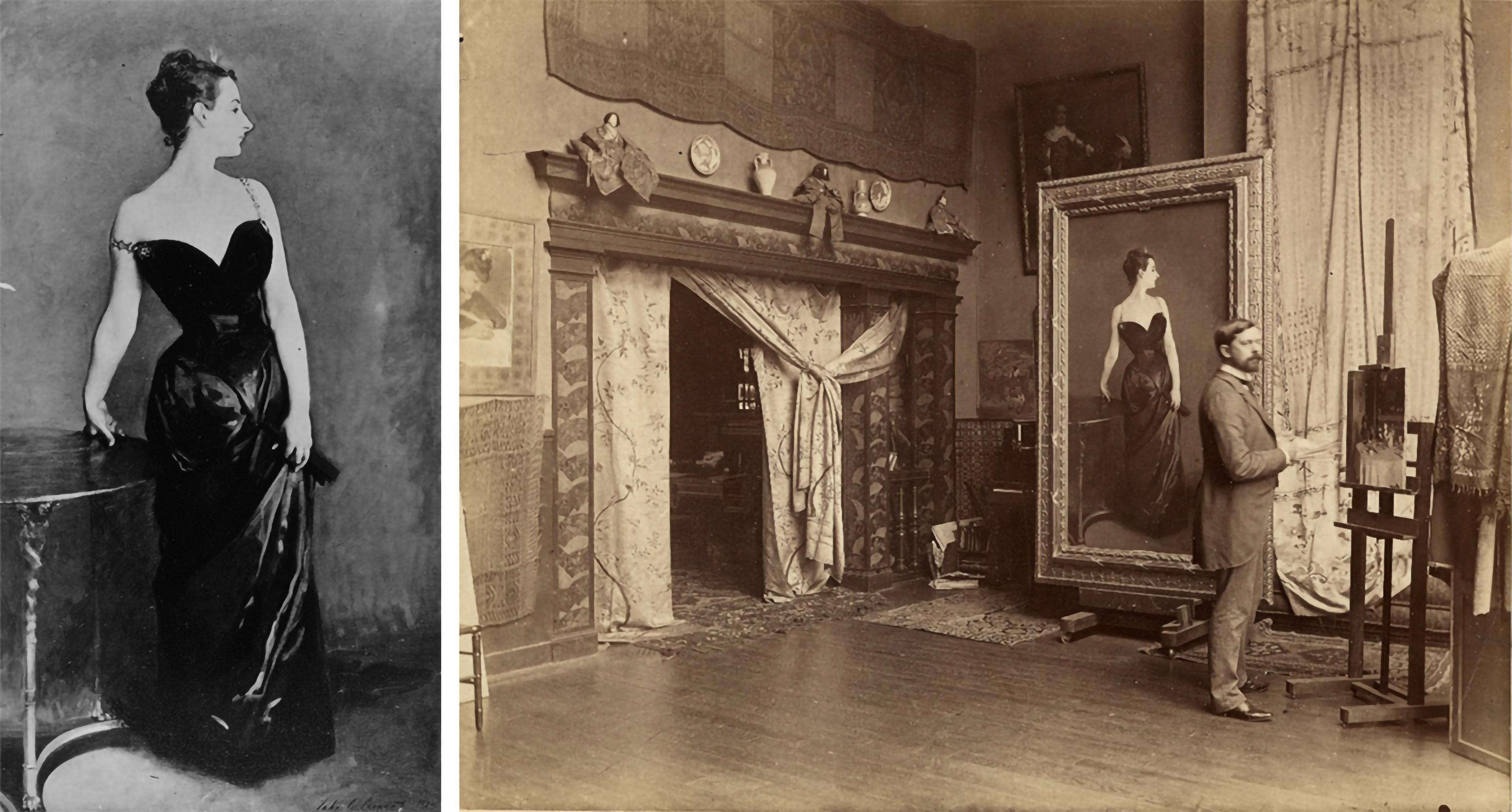

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Madame X (Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau), 1883–84. Oil on canvas, 82 1/8 x 43 1/4in. (208.6 x 109.9cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Arthur Hoppock Hearn Fund, 1916 (16.53)

Sargent worked with obsessive intensity to capture the exotic, even bizarre appearance of Madame Gautreau, an American from New Orleans married to a wealthy Parisian banker. Sargent described her as having the most beautiful lines, and skin of a “uniform lavender or blotting-paper colour all over.“[3] Reputedly, she tinted her auburn hair with henna and used chlorate of potash powder to enhance her naturally fair complexion.

It has long been known, from various letters and accounts, that Sargent made significant alterations to the work. It wasn‘t until 1995, however, that technical examination including X-radiography and infrared reflectography uncovered multiple changes Sargent made while finishing the portrait for the Salon of 1884.[4] The X-radiograph of the head reveals numerous adjustments to the profile, a significant shift in the position of the ear, and changes to the positions of the arms.

X-radiographs of the torso and head show numerous changes by the artist. An outline of the painted surface is superimposed on the X-radiograph

It was Sargent‘s practice to keep photographs of his paintings, and a unique image of the portrait as it appeared at the Salon was included in a gift from Sargent's sister to the Museum. The painting seen in the photograph was not well received; Sargent‘s creative experiment was a disaster for both him and for the reputation of Madame Gautreau. “There was a grand tapage (uproar) before it all day…I found him [Sargent] dodging behind doors to avoid friends who looked grave…I was disappointed in the colour. She looks decomposed. All the women jeer. Ah voilà ‘la belle!‘ ‘Oh quell [sic] horreur!‘ (“Oh there is ‘the beauty!‘ Oh what a fright!“) etc….All the a.m. it was one series of bons mots, mauvaises plaisanteries (puns, bad jokes) and fierce discussion. John, poor boy, was navré (heartbroken).“[5]

Left: The painting as it appeared at the Salon of 1884, with the right strap fallen over the shoulder. Right: A photograph of Sargent’s studio from 1885 shows an adjustment to the right strap, as it is today

An 1885 photograph of Sargent in his studio is the first record of the artist‘s subsequent changes to Madame X, most notably to the position of the right strap. Less obvious are the remarkable adjustments to the background. Visitors to Sargent‘s studio had commented that the palette was “blue, green, white and black“[6]; Sargent himself described his dissatisfaction in a letter to a friend, and “dashed a tone of light rose over the former gloomy background.“[7] Because Sargent repainted while the portrait was still framed, a glimpse of the wildly different color is visible along the edge. Ultimately for the final depiction Sargent chose the more neutral color that we see today.

The original background color is still visible at the painting‘s edges

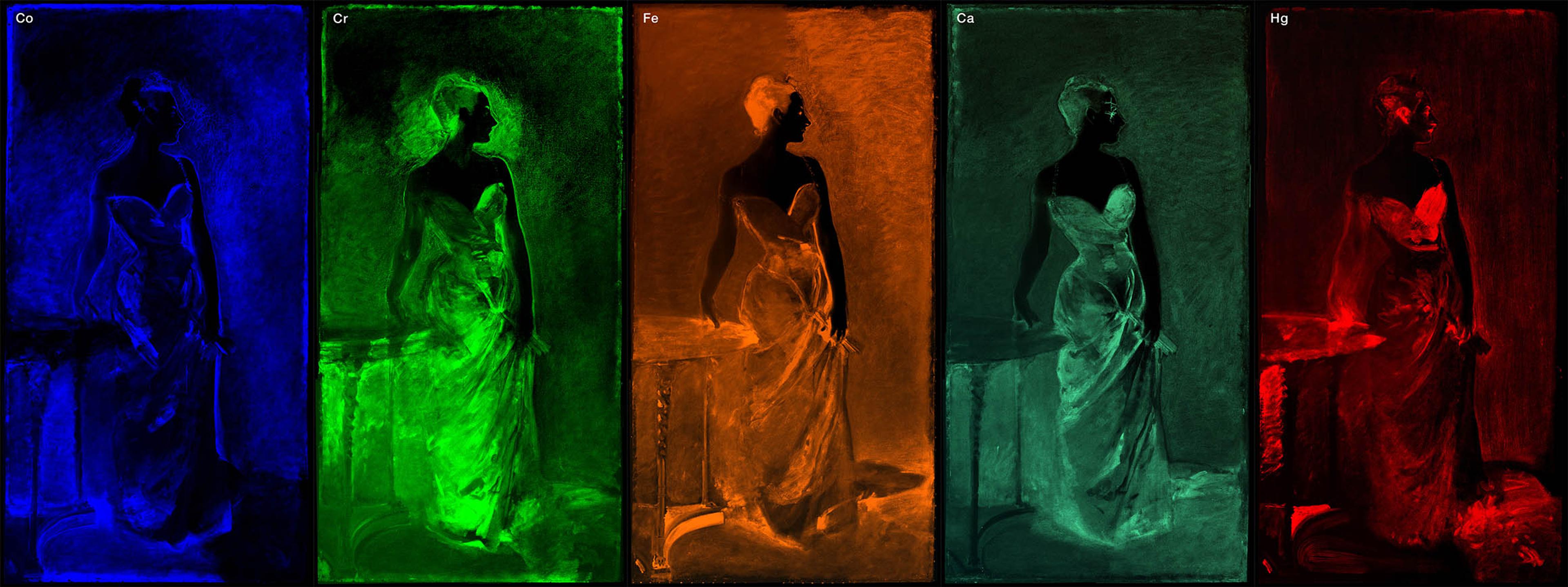

While the 1995 study characterized the changes in color to a limited degree, increased technical capabilities have since provided a closer look at these extraordinary transformations. Scanning X-ray fluorescence (XRF) provides a mapping of the individual elements present throughout the painting.

The XRF maps record, from left to right, the presence of the intensely blue pigment cerulean (Co); the green pigment viridian (Cr); iron-rich pigments such as brown, red, and yellow earths (Fe); bone black as well as the earth color used for the final background (Ca); and the opaque red pigment vermilion (Hg)

The XRF maps (above) record the presence of elements composing various pigments such as cerulean, viridian, and vermilion. Perhaps most surprising are the copious amounts of dark and translucent viridian green found in the deep black dress and the sitter‘s rich, reddish-brown hair, or the sparing use of vermilion to color the flesh. Although traces of fiery red vermilion are present in the eye, nostrils, lips, ear, bodice, and right arm, for the pale flesh tone of the chest and left arm the artist preferred a subtler transparent red lake pigment, which achieves a delicate, more naturalistic color.

These astonishing images are a testament not only to Sargent‘s strength as a colorist, but also to his involved creative process. They offer a window on the artist‘s mind at work, illustrating with clarity and precision the many choices a painter makes before completing a composition, and serve as a vivid reminder that every detail of the finished surface is the result of many decisions that remain invisible to the naked eye.