The Met’s Egyptian Expedition, led by Herbert Winlock, discovered a number of embalming caches during their excavations in the ancient cemeteries on the western bank at Thebes (modern Luxor). These deposits included material such as bags of natron and sawdust and vessels of various sizes that were used during the mummification process. Made sacred through contact with a deceased individual, these items were carefully collected and buried separately from the body. Some caches comprised only pottery and bags of embalming materials, but others included a coffin used as a container.[1]

Figure 1. Three views of Late Embalming Cache II during excavation (left to right): the pit when first uncovered (M5C 30); with one layer of material removed (M5C 32); with two layers removed (M5C 33). Photographs by Harry Burton, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art Archives

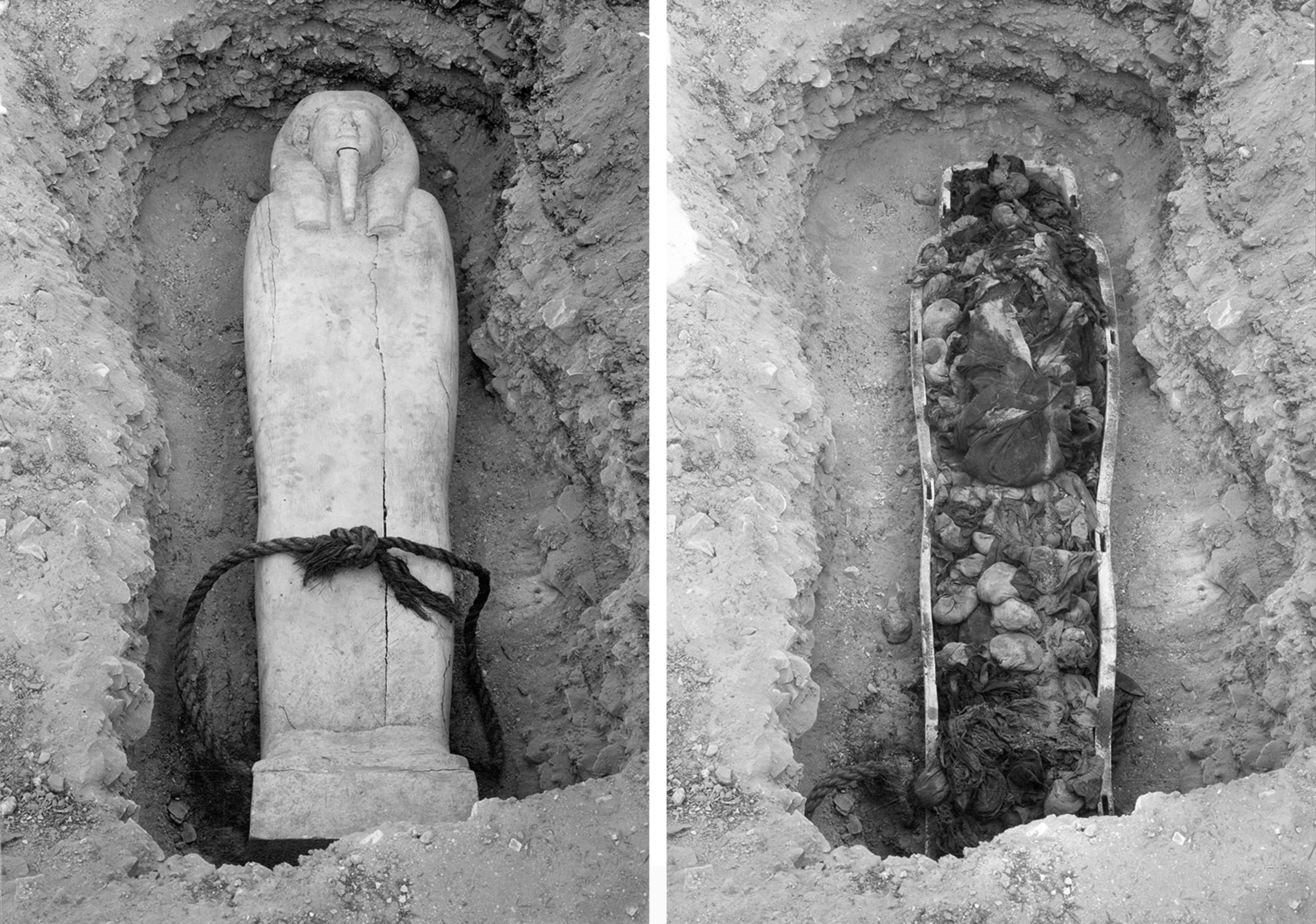

During the 1923–24 season, Met archaeologists uncovered several embalming caches dating to the late second and early first millennium in the courtyards of the much earlier Hatshepsut temple (built around 1450 BCE) on the West Bank of Thebes at Deir el-Bahri. This coffin (26.3.13a, b) was at the bottom of Late Embalming Cache II, an irregular pit measuring 220 x 120 cm long and 90 cm deep cut into the southeast court of the temple. When the team began their excavations, they found, just under the surface, parts of a frame made of papyrus and palm stems (Figure 1a). This was badly broken and was discarded after photography. In the next layer was a grass mat that had been rolled up and tied with a cord (Figures 1b and 1c). Underneath this was a reed mat, folded over several funerary garlands, and then a deep stratum of barley tibn (straw) and wreaths. Some of this material may have been used in rituals enacted on the day of the burial (see Tutankhamun’s Funeral).

Figure 2. The embalming coffin (26.3.13a, b) in situ within the pit, with the rope used to lower it into place still around the legs (M5C 34); the coffin with the lid removed, showing the content (M5C 35). Photographs by Harry Burton, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art Archives

The coffin lay at the bottom of the pit, with straw and chaff packed tightly around it. A 4-ply rope of halfa grass, likely used to lower the filled coffin into the pit, was still looped around its legs (Figure 2). Seven large pots had been placed on and around the coffin—similar to the arrangement seen around a burial in the much earlier tomb of the high steward Ipi (around 2000 BCE),[2]—and a deposit of smaller vessels, all broken, lay on top of the face and left shoulder. Numerous bundles of natron and sawdust tied up in pieces of linen had been packed inside the coffin box, while many of them were still wet (Figure 2), as can be seen by their squashed shape.

Coffin

The coffin (Figure 3), which was given to The Met by the Egyptian government, takes the shape of a sah, a body that has been properly prepared for burial. The arms and legs are obscured, as if wrapped, their shapes indicated only through subtle contouring and modeling. The short pedestal supporting the figure associates the coffin with a statue. Wearing a tripartite wig and long curled beard, the head emerges from the shoulders, symbolizing the transformed spirit entering eternal life. The shape of the coffin, including the relatively flat head and shallow pedestal but no carved back pillar, suggests a date in the 25th or early 26th Dynasty (around 700 BCE).[3] The pottery found in the cache supports this dating (see below, Pottery). As noted by the excavators, this coffin was unfinished, buried “just as it came from carpenter’s to decorator’s.”[4]

Figure 3. Undecorated Coffin, from Thebes, Deir el-Bahri, Embalmers’ Cache II. Third Intermediate Period to Late Period (700–650 BCE). Wood, paste, paint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1926 (26.3.13a, b). Photographs by Anna-Marie Kellen

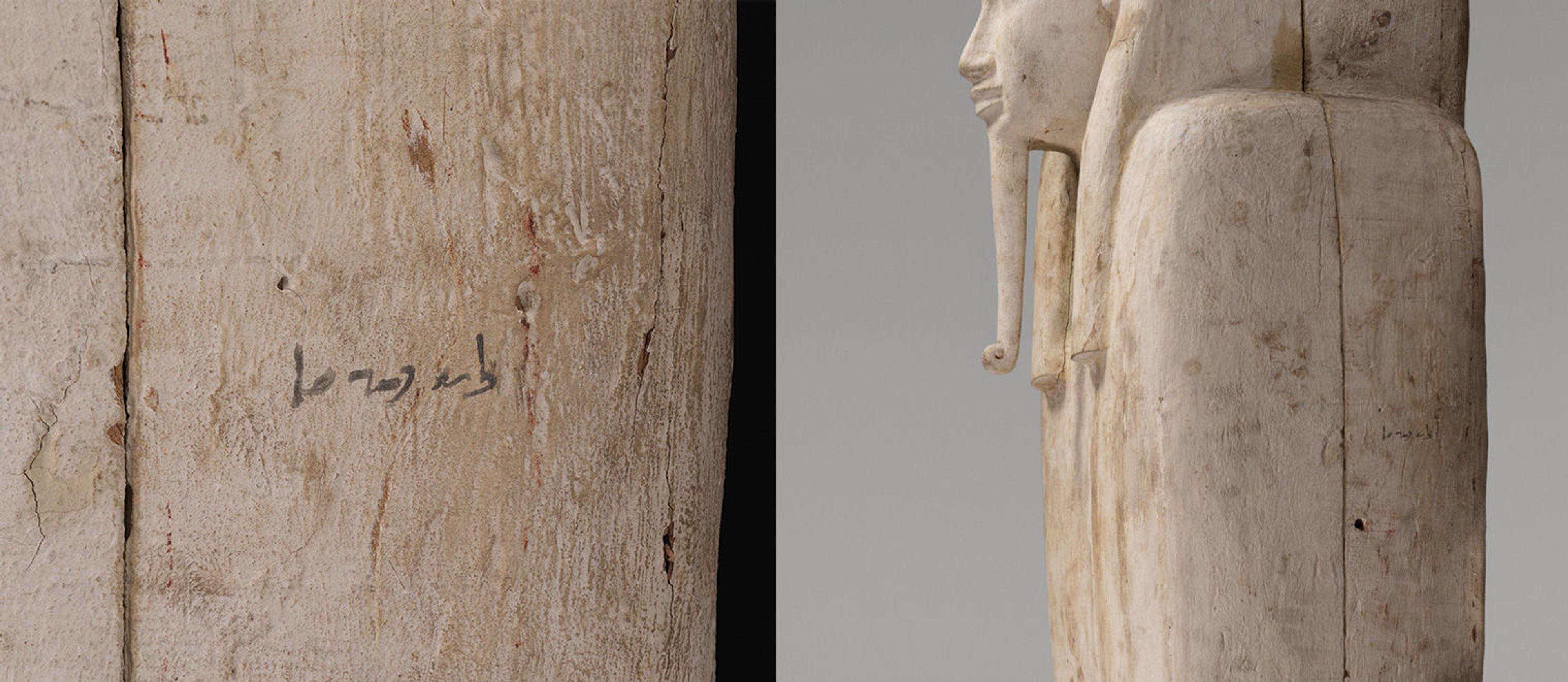

Inscription

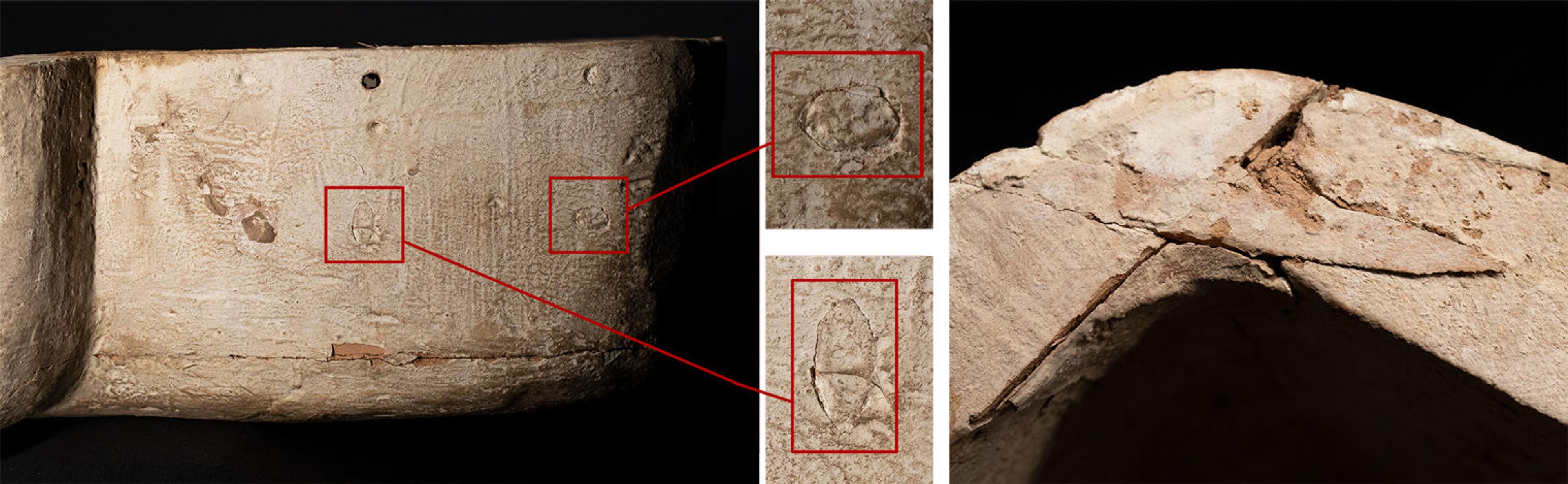

An inscription in abnormal hieratic (Figure 4), a cursive script used during the later pharaonic period at Thebes, had been painted on the left side, just below the shoulder. This has been read by Günter Vittmann as the name xAm-Hr, “Khamhor.”[5] Vittman further suggests that this could be Khamhor (C), son of Raemmaakheru and Kakaiu, who was a member of the great Mentuemhat family that held power in Thebes during the late 25th and early 26th Dynasties (around 700–650 BCE). A priest of the god Montu and Stolist of Thebes, Khamhor C is known from inscriptions on several block statues,[6] a Book of the Dead papyrus, and the lid of what is presumed to be the coffin in which he was actually buried.[7] His father Raemmaakheru was a high-ranking official whose numerous titles included Priest of Montu; Mayor of Thebes, Vizier, and Defender of the City; his grandfather Pakherer/Harsiese and great-grandfather Khamhor (A) were also viziers.[8]

Figure 4. Shoulder and close-up of the shoulder of coffin MMA 26.3.13a, b, showing the label saying "Khamhor" in abnormal hieratic. Photographs by Anna-Marie Kellen

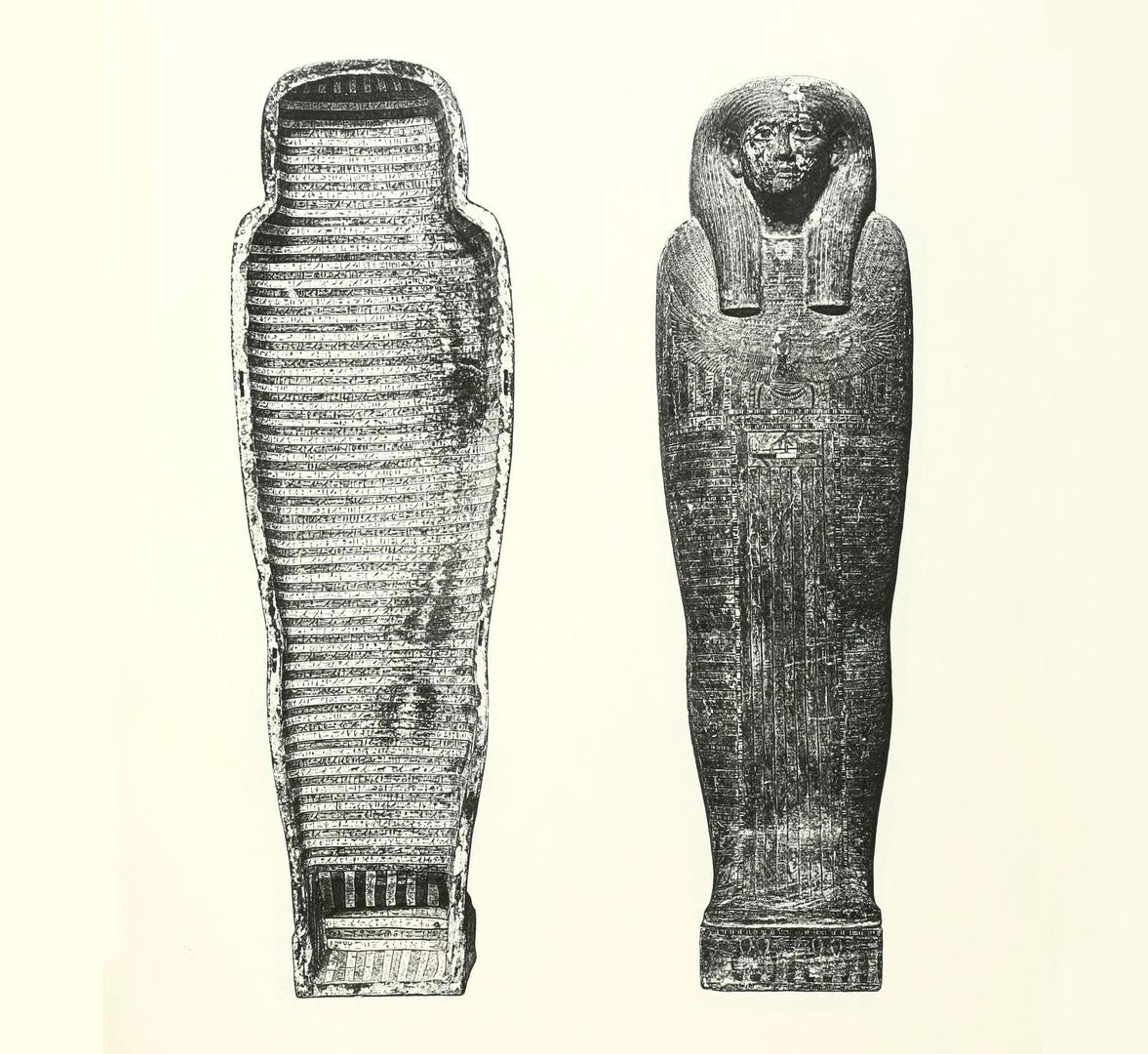

Khamhor C’s coffin lid, now in Cairo (EMC CG 41068) is said to have been discovered in 1858 in a shaft dug into the floor of the much earlier (around 1450 BCE) Hatshepsut temple.[9] Most of Khamhor C’s Book of the Dead, which also would have been part of his burial, was discovered by Winlock in the mouth of a nearby pit tomb (MMA 57), where it had blown, perhaps after being discarded by ancient robbers. Thus, the presence in the same area of a "embalming" coffin labeled with Khamhor’s name strongly suggests that the materials found inside were used for Khamhor's own mummification and funerary rites.[10]

Figure 5. Coffin lid of Khaemhor, Cairo, CG 41068 (from Gauthier, Cercueils anthropoïdes des prêtres de Montou, pl. 39)

Material and Construction

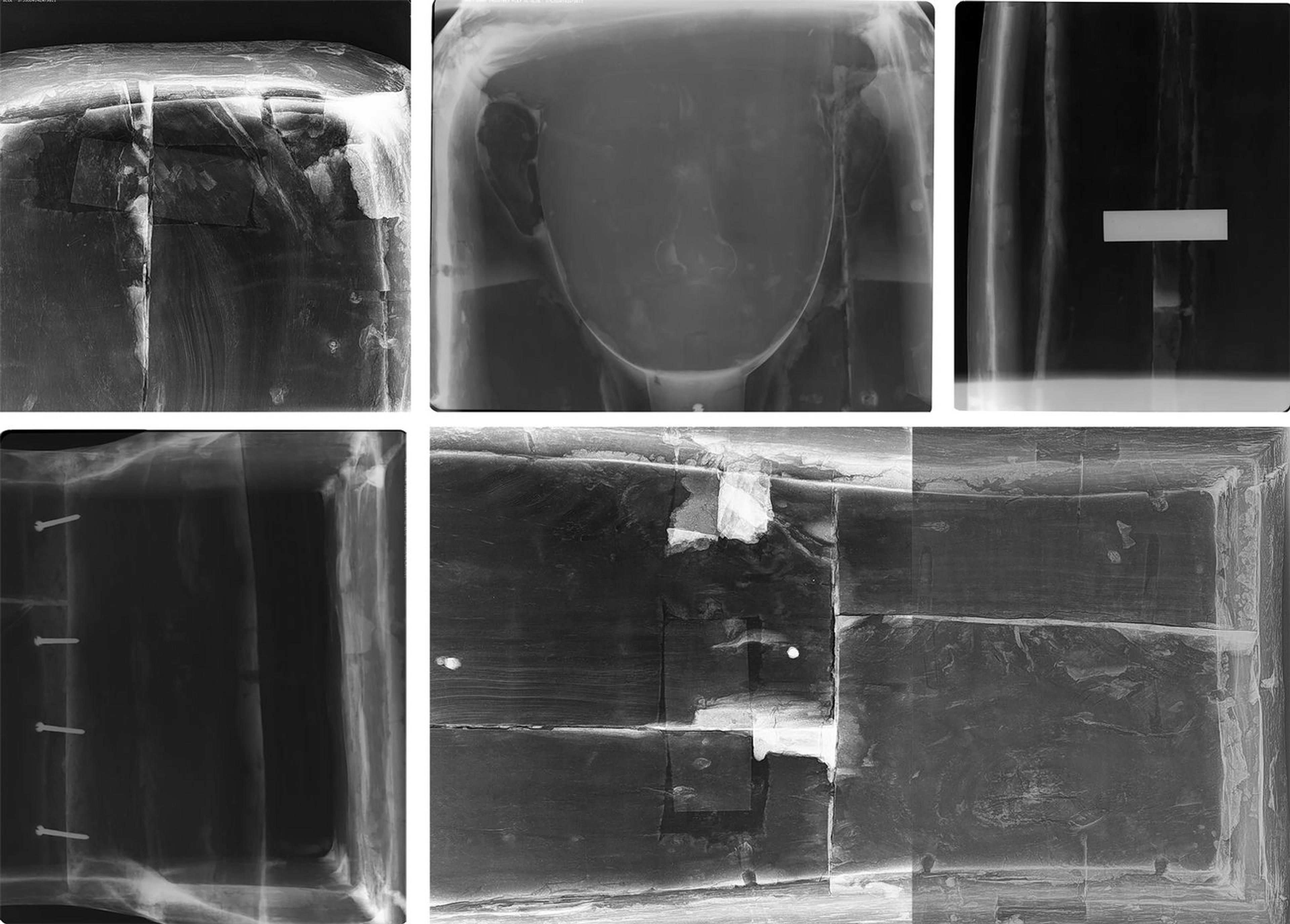

The coffin is constructed from wood and covered by a fairly coarse layer of white paste, [11] but it is otherwise unadorned. The white paste, which is composed of calcium carbonate and an organic binder, coats the interior and exterior surfaces of the coffin and is perhaps meant to imitate costlier and more desirable limestone. Visual examination and X-ray radiography reveal that the box is made from at least eight separate wooden boards, the lid is made from at least ten wooden boards, and the face, wig lappets and long beard were carved separately and attached. The quality of the carving of the face, wig, and beard is relatively high, although the mouth is somewhat lopsided. Some of the joining mechanisms used to attach these various components are visible with the naked eye while others can only be seen in X-ray images. Interestingly, X-ray images show us that some of the holes drilled to accommodate wooden dowels are either empty or filled with paste. Similarly, at least one tenon appears to have been sawn through. These structural modifications are likely an indication that at least some components of the coffin were reused.

Figure 6. Computed X-ray radiographs showing sawn-through tenon (upper left), separately carved and attached face (upper center), modern hardware (upper right and lower left), and various tenons and dowel holes within the boards of the box (lower right)

The box and lid were originally secured with mortise and tenon closures, which were further secured with dowels. One of these dowels is visible where the white paste layer has fallen off, while others are still covered with white paste, implying that the dowel was inserted before the surface was finished.

Figure 7. Ovoid-shaped dowels—perhaps implying that they have been cut down at an angle—covered with paste

In many areas, a coarse pinkish paste is visible beneath the white. Such pastes were often used to round out corners, fill gaps in the wood, and smooth out joins. On this coffin, the pinkish paste was used both as a gap-filler and as a preparatory layer before the white paste was applied. Brush strokes visible throughout the white paste layer seem to indicate that it was applied fairly rapidly with a relatively coarse brush made of vegetal fibers.

Figure 8. Coarse brush strokes visible in the paste layer on the outside of the box

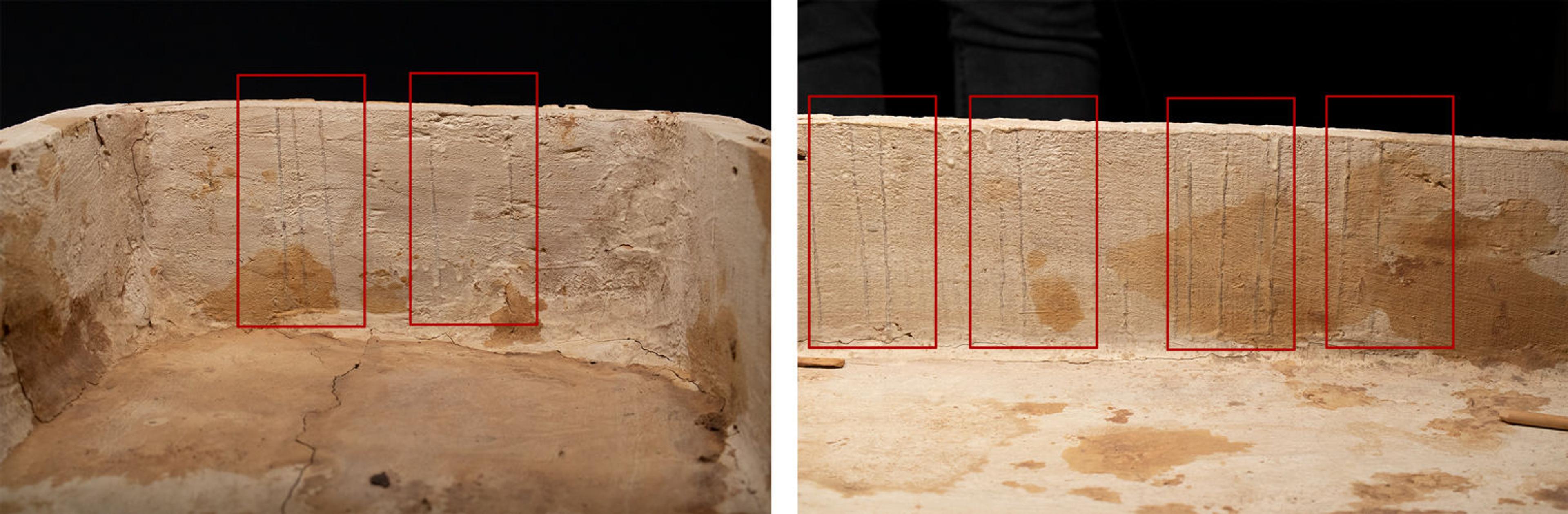

Thin, slightly raised lines are visible along the interior sides of both the box and lid, consisting of a dark brown material. These lines sit directly on the wood, below the paste layer. Some of the lines on the lid match up spatially with lines on the box, while others do not. Several of the same lines are also present on the exterior sides of the box and on the interior back surface of the box in the head area. Analysis with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy determined that the material is a proteinaceous (animal-derived) glue.[12]

Pooling of the glue shows the orientation of the wooden panels when the substance was applied—the drips run from the lid towards the box. It is possible that the sides of the coffin were once a single board to which a somewhat drippy liquid glue was applied along the edge. At a later date, that board was cut in half and reused as the coffin’s sides. While this explanation cannot be proven, similar glue drips were also noted along the edge of the coffin of Padi-iset in Vienna (ÄS 3940a).

Figure 9. Raised lines of proteinaceous glue on interior of coffin box

Several blackish marks along the proper left side of the box appear to be fingerprints, possibly left behind by the people who loaded the various embalming materials into the coffin. There is brownish staining in the interior of the box, concentrated particularly in the head area and in the center. Similar staining is also visible on the back of the box, in the head area. Some of this same material is present on the side and proper left rim of the box, corresponding to a similar stain on the proper left side/rim of the lid. There is a small fragment of textile stuck to the stained wood in the head area. It is likely that the staining is associated with the materials packed into and/or around the coffin. Analysis with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Gas Chromatography/Mass-Spectrometry determined that the stains have variable compositions of lipids, oxidized components of Pinaceae resins, and beeswax. Some of the lipids present may come from the body in which the sacks of natron and straw were originally packed as part of the mummification process.[13]

Figure 10. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence image of the coffin lid exterior showing the previous conservation, and the box interior, showing orange-fluorescing stains for the embalming materials that were there before.

In addition to observations about the coffin’s construction and the ancient materials present on its surface, details about modern repair and restoration were recorded. Three metal bars were screwed into the lid, on the interior, bridging large cracks in the wood. Four modern metal nails, used to connect two panels in the foot area of the lid, are also visible in X-ray images. Some of the cracks have been filled with modern plaster, which is readily distinguished when viewed under UV radiation.

Pottery

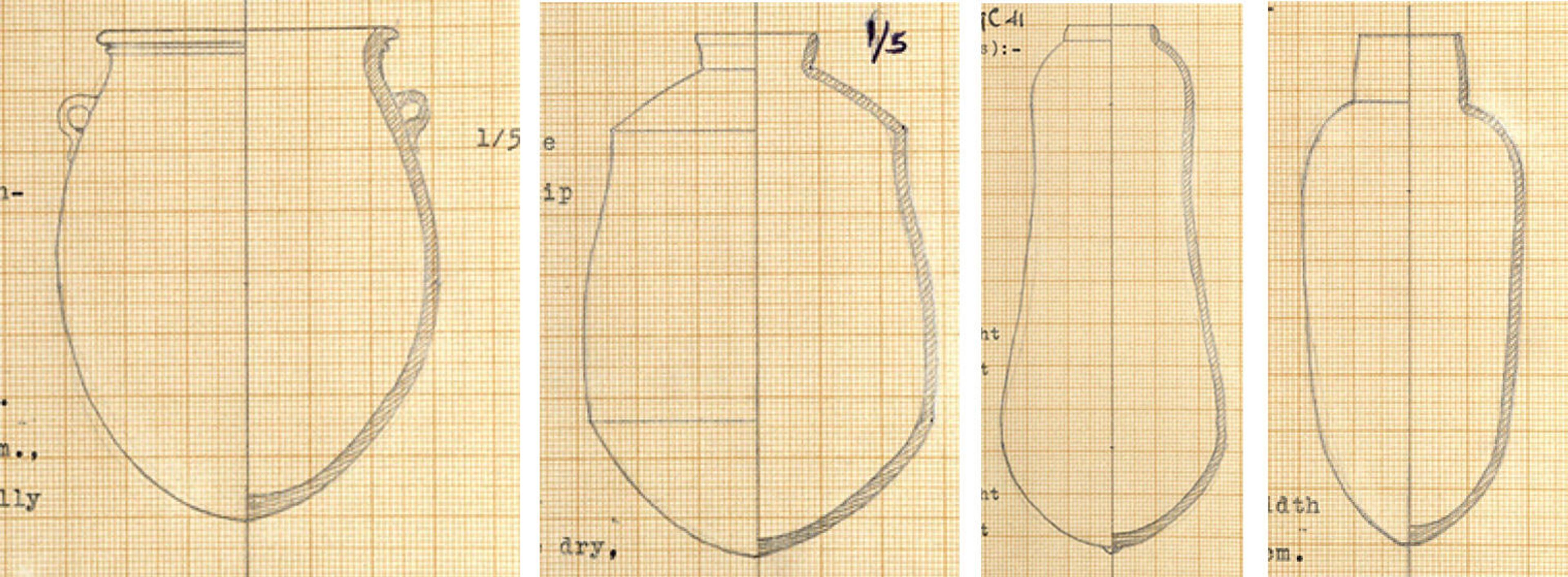

Seven large pots had been placed around the coffin. None of these were drawn, photographed, or brought back to the Museum, but comparison with similar vessels from other assemblages (see Figure 11) confirms a date for the deposit in the late seventh to sixth centuries BCE.[14]

Figure 11. Pots comparable to those found with 26.3.13a, b, from a nearby cache at Deir el-Bahri (Theban Tomb Cards 165, 167, 168, 170).The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art Archives

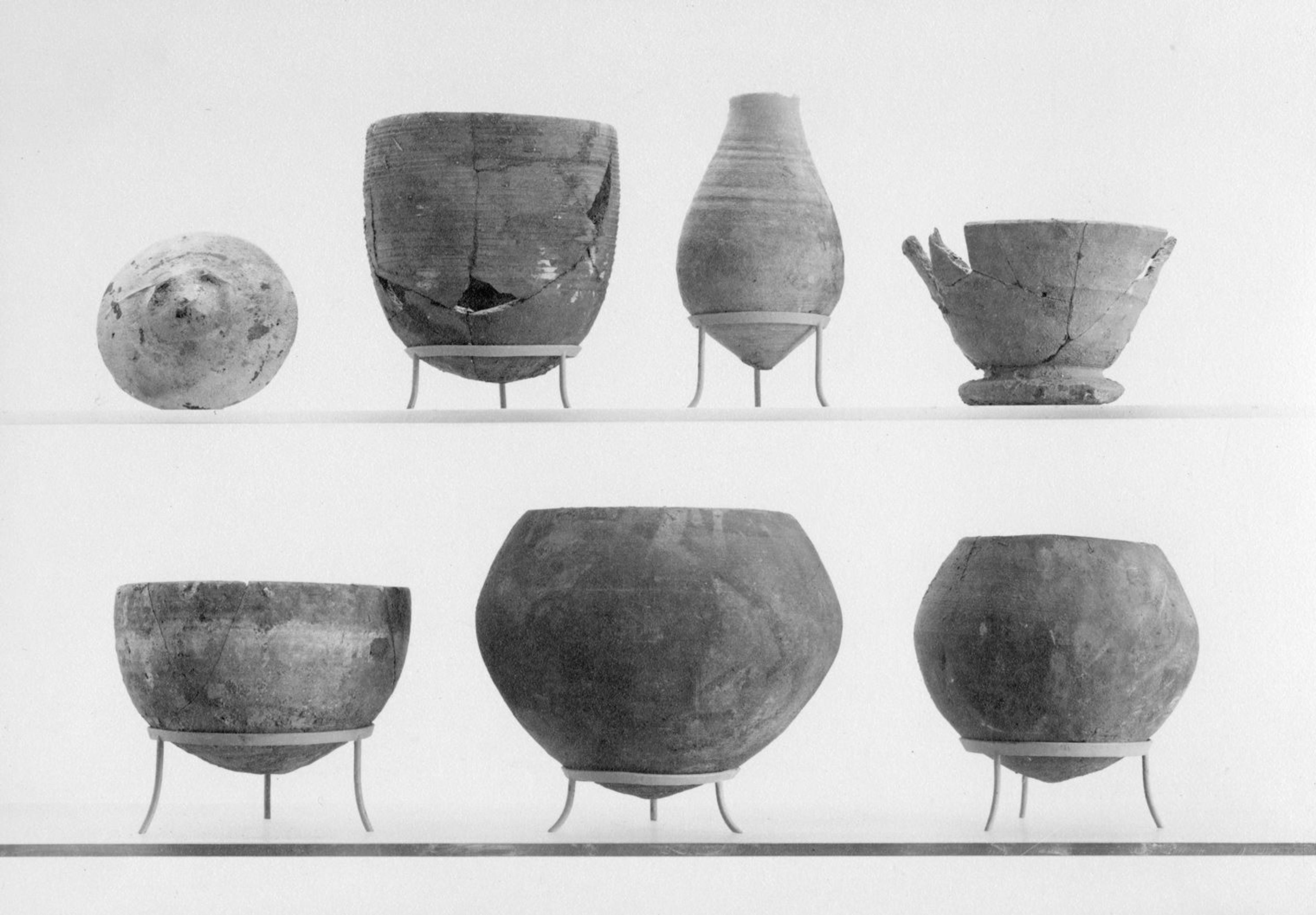

Several of the smaller vessels in the deposit (Figure 12) were awarded to The Met as partage by the Egyptian government and accessioned at The Met as MMA 28.3.173 and 28.3.174. These were deaccessioned in 1953 and are now in the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (formerly the Oriental Institute) of the University of Chicago, as E29286 and E29287, respectively.

Included in Winlock’s notes are mentions of materials found in some of these vessels. For example, he states that one pot was half full of low-grade natron, on top of which wreaths had been packed. In addition, he says that some of the smaller bowls and jars had been stained with oil, and in some cases showed traces of natron as well. He saw evidence that some of the round-bottomed bowls had stood upright in the dirt while they were full of an oily substance, and several were missing pieces, indicating that they were broken, probably deliberately, before they were buried. He suggested that MMA 28.3.173 [D] had been used as a container for oil, some of which still remained on the interior along with traces of natron and barley chaff; a black oily substance with barley chaff still adhered to the outside of the foot. It is possible that at least some of the materials he identifies as oil were similar to the mixture of oil, fat, and oxidized Pinaceae resin we identified from stains on the coffin.

Figure 12. Seven smaller vessels from the deposit (M9C 48). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Egyptian Art Archives

Discussion

Embalming caches formed an important part of the mortuary landscape of ancient Egypt. These deposits contained the materials used during the mummification process, which served to transform the body of the deceased into a sah, a being capable of entering the realm of the divinized dead, as well as objects that appear to come from the funeral rites. In some cases, the pottery, linen, natron, garlands, and other bits and pieces made sacred through this ritualized contact were simply collected and buried in a pit. In others, as is the case here, much of the material was first placed inside a coffin and then put into the ground. Examples are also known of tombs filled with embalming material, including coffins not used for burials (as in KV 63, dating from the late 18th Dynasty, around 1300 BCE).

A number of coffins used for embalming materials are known from the Theban region.[15] Some are crude, clearly made specifically to hold the cast-off items from the mummification and burial of an individual.[16] Others appear to have been made and decorated for the burial of a body, and then used instead for embalming material.[17] The coffin under study here may fall somewhere between these two use-cases—it is well-made (from reused wood, as was often the case for coffins in general), but rather than being decorated, was simply covered with paste, labeled with the name of Khamhor, and then used to bury embalming materials. We cannot tell whether it was originally meant to be finished and used for the burial of his (or someone else's) body, or made specifically as an “embalming” coffin. In any case, connecting this coffin to Khamhor C, a member of one of the most powerful Theban families of the late 25th and early 26th Dynasties, and a man who is known to have been buried at Deir el-Bahri in another coffin, adds to our understanding of the mortuary landscape and practices of this era.

Footnotes

[1] Cf. David Aston, “The Theban West Bank from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty to the Ptolemaic Period,” in The Theban Necropolis: past, present and future, eds. Nigel Strudwick and John H. Taylor (London: British Museum Press, 2003), pp. 153–54 (Type A); Salima Ikram and María López-Grande, "Three embalming caches from Dra Abu el-Naga,” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 111 (2011), pp. 205–28.

[2] As noted by Jonathan Paul Elias, Coffin Inscription in Egypt after the New Kingdom: a study of text production and use in elite mortuary preparation, II (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI, 1993), p. 255; see Erhart Graefe et al., Das Grab des Ibi, Obervermögenverwalters der Gottesgemahlin des Amun (thebanisches Grab Nr. 36): Beschreibung und Rekonstruktionsversuche des Oberbaus. Funde aus dem Oberbau (Bruxelles: Fondation Egyptologique Reine Elisabeth, 1990) vol. l, pp. 21–25; Klaus P. Kuhlmann and Wolfgang Schenkel, Das Grab des Ibi, Obergutsverwalters der Gottesgemahlin des Amun. Thebanisches Grab Nr. 36. Band 1: Beschreibung der unterirdischen Kult- und Bestattungsanlage (Mainz: Philip von Zabern, 1983).

[3] See John H. Taylor, “Theban Coffins from the Twenty-Second to the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty: Dating and Synthesis of Development,” in The Theban Necropolis: past, present and future, eds. Nigel Strudwick and John H. Taylor (London: British Museum Press, 2003), pp. 113–14; Elias, Coffin inscription II, p. 254, n. 61.

[4] Winlock, Theban Tomb Card 192.

[5] Personal communication, Vittman to Kamrin (email, March 5, 2023)

[6] Two of these (CG 42249, see Georges Legrain, Statues et statuettes de rois et de particuliers, vol. 3 (Le Caire: Imprimerie de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1913), pp. 101–102, pl. 52 and CG 48629, see Jack Josephson and Mahdouh Mohamed El-Damaty, Catalogue général of Egyptian antiquities in the Cairo Museum. Nrs. 48601 - 48649: statues of the XXVth and XXVIth Dynasties (Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities, 1999), pp. 66–67; pl. 29) are inscribed Raemmaakheru, but also bear text saying they were made by Khamhor for his father; the third (CG 42250, see Legrain, Statues et statuettes de rois et de particuliers, vol. 3, pp. 102–103) was made for Khamhor himself. For additional information and references about these three statues, see also the IFAO Karnak Cachette website, CK 519, CK 671, and 159, respectively.

[7] See Henri Gauthier, Cercueils anthropoïdes des prêtres de Montou (Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1913), pp. 469–97, pl. 39.

[8] For discussion of Khamhor C and his family, see Günther Vittmann, Priester und Beamte im Theben der Spätzeit: genealogische und prosopographische Untersuchungen zum thebanischen Priester- und Beamtentum der 25. und 26. Dynastie (Wien: AFRO-PUB, 1978), pp. 34–37, 49–152, 169; Christopher Hugh Naunton, “Regime Change and the Administration of Thebes during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty” (PhD dissertation, Swansea: Swansea University, 2011), pp. 29–30; Elias, Coffin Inscription II, pp. 251–53.

[9] For a review of the history of these discoveries, see Cynthia Sheikholeslami, “The Burials of Priests of Montu at Deir El-Bahari in the Theban Necropolis,” in The Theban Necropolis: past, present and future, eds. Nigel Strudwick and John H. Taylor (London: British Museum Press, 2003), pp. 131–37.

[10] Based on the findspot of this coffin, Jonathan Elias had suggested in 1993 that it might in fact belong to Khamhor C (Elias Coffin Inscription II, p. 255).

[11] Helen Strudwick and Julie Dawson (eds), Death on the Nile: Uncovering the Afterlife of Ancient Egypt (Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam Museum : D Giles Limited, 2016).

[12] Analysis was carried out by Adriana Rizzo in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Department of Scientific Research.

[13] Analysis was carried out by Adriana Rizzo in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Department of Scientific Research.

[14] Cf. Aston, “The Theban West Bank," p. 152, fig. 10.

[15] For a partial list, see Aston, “The Theban West Bank,"pp. 153–54; also Ikram and Lopez-Grande, “Three embalming caches"; Ikram in preparation.

[16] An example of this can be seen for a Lady of the House, Wedjaresen, daughter of a Montu priest named Pakhtiu and her mother, the Lady of the House Nesikhonsu. High quality coffins for both Wedjaresen and Nesikhonsu are known (New York, MMA O.C.22a, b and Cairo, CG 41025, with outer qersu coffin CG 41003); in the 1960s, the Polish expedition to Deir el-Bahri discovered poor quality coffins containing embalming material inscribed for each of these women (see Elzbieta “Coffins found in the area of the temple of Tuthmosis III at Deir el-Bahari,” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 66 (1968), pp. 171–81).

[17] See for example the coffin of Namenkhamun (Boston, BMFA 94.321).

References

Aston, David A. “The Theban West Bank from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty to the Ptolemaic Period.” In The Theban necropolis: past, present and future, edited by Nigel Strudwick, and John H. Taylor, pp.138–66. London: British Museum Press, 2003.

Dąbrowska-Smektała, Elzbieta. “Coffins found in the area of the temple of Tuthmosis III at Deir el-Bahari.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 66 (1968), pp. 171–81.

Elias, Jonathan Paul. Coffin Inscription in Egypt after the New Kingdom: a study of text production and use in elite mortuary preparation, 4 vols. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI, 1993.

Gauthier, Henri. Cercueils Anthropoïdes des Prêtres de Montou. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1913.

Graefe, Erhart, et al. Das Grab des Ibi, Obervermögenverwalters der Gottesgemahlin des Amun (thebanisches Grab Nr. 36): Beschreibung und Rekonstruktionsversuche des Oberbaus. Funde aus dem Oberbau. Bruxelles: Fondation Egyptologique Reine Elisabeth, 1990.

Ikram, Salima and María J. López-Grande. “Three embalming caches from Dra Abu el-Naga.” Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 111 (2011), pp. 205–28.

Josephson, Jack A. and Mamdouh Mohamed Eldamaty. Statues of the XXVth and XXVIth Dynasties. Catalogue général of Egyptian antiquities in the Cairo Museum. Nrs. 48601 - 48649. Cairo: Supreme Council of Antiquities, 1999.

Kuhlmann, Klaus P. and Wolfgang Schenkel. Das Grab des Ibi, Obergutsverwalters der Gottesgemahlin des Amun (thebanisches Grab Nr. 36): Band 1: Beschreibung der unterirdischen Kult- und Bestattungsanlage. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 15. Mainz: Philip von Zabern, 1983.

Legrain, Georges. Statues et statuettes de rois et de particuliers, vol. 3. Catalogue général des antiquités égyptiennes du Musée du Caire 71. Le Caire: Imprimerie de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 1914.

Naunton, Christopher Hugh. “Regime Change and the Administration of Thebes during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.” PhD Dissertation, Swansea University: Swansea, 2011.

Sheikholeslami, Cynthia May. “The Burials of Priests of Montu at Deir El-Bahari in the Theban Necropolis.” In The Theban Necropolis: Past, Present and Future, edited by Nigel Strudwick and John H. Taylor, pp. 131–37. London: British Museum Press, 2003.

Strudwick, Helen, and Julie Dawson (eds). Death on the Nile: uncovering the afterlife of ancient Egypt. Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam Museum : D Giles Limited, 2016.

Taylor, John H. “Theban Coffins from the Twenty-Second to the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty: Dating and Synthesis of Development.” In The Theban necropolis: past, present and future, edited by Nigel Strudwick and John H. Taylor, pp. 95–121. London: British Museum Press, 2003.

Vittmann, Günther. Priester und Beamte im Theben der Spätzeit: genealogische und prosopographische Untersuchungen zum thebanischen Priester- und Beamtentum der 25. und 26. Dynastie. Veröffentlichungen der Institute für Afrikanistik und Ägyptologie der Universität Wien 3; Beiträge zur Ägyptologie 1. Wien: [Afro-Pub], 1978.