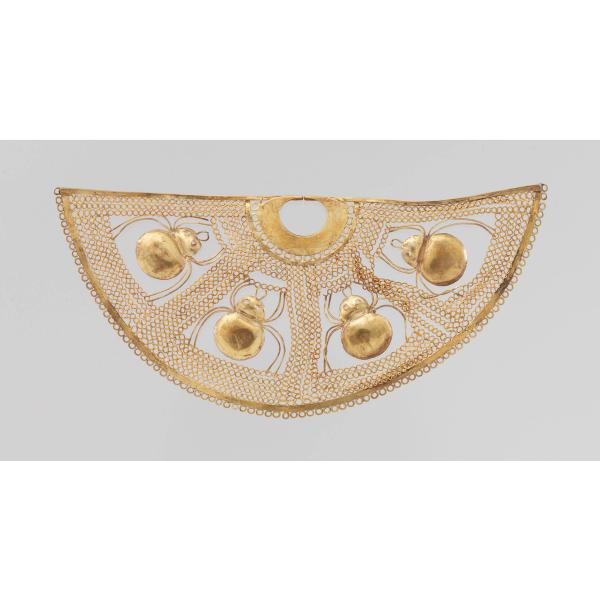

Nose Ornament with Spiders

Spider imagery appears in Andean works of art from the middle of the first millennium BCE until the Spanish Conquest in the sixteenth century. Spiders were particularly important within the cosmology of Peru’s North Coast for their ability to catch and kill live prey, a skill that linked them to warfare and ritual sacrifice. The Moche, who flourished in this region from 200–850 CE and who are thought to be the cultural successors to (if not the direct descendants of) the Salinar, may have even seen the spider’s practice of ensnaring its victim in a web and draining vital fluids as analogous to the way a warrior captured an enemy with ropes and extracted blood. In the North Coast, spiders were further understood to be harbingers of agricultural fertility, as they often appeared before rainfall, an important life-sustaining resource in the arid, desert-like environments of coastal Peru.

Nose ornaments, worn suspended from the nasal septum and often covering the mouth and lower face, were made for high-status individuals. These and other body adornments were likely used in the ancient Americas as material expressions of position and power. Frequently found on or near an interred individual as salient features of elite burials, such ornaments were also thought to identify the status of the interred in the afterlife, distinguishing the wearer even in death.

Technical Analysis

Deborah Schorsch, Objects Conservator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, notes that Salinar ornaments are frequently characterized by a generous and innovative use of wire, a predilection for soldered rather than mechanical joins, and a preference for minimally volumetric forms. Schorsch’s studies of this nose ornament have further revealed that the spiders’ reductive bodies were cut out from gold sheet that was slightly bowed to indicate the abdomen and cephalothorax (fused head and thorax). The eyes have been perforated from the underside and the burrs polished to create flattened rims. Two square-section wires were joined side by side with solder and to the underside of the spiders’ bodies to form eight legs; two additional square wires were soldered to the underside of each head to create the pincers. The curlicue webs were fashioned from multiple pairs of round wires that were hammered and/or abraded flat on the front and back, especially where they overlap, and then soldered together. Hammered sheets or strips and flattened round wires form additional elements.

References

Alva Meneses, Néstor Ignacio. 2008. “Spiders and Spider Decapitators in Moche Iconography: Identification from the Contexts of Sipán, Antecedents, and Symbolism.” In The Art and Archeology of the Moche: An Ancient Andean Society of the Peruvian North Coast, edited by Steve Bourget and Kimberly L. Jones, 247-261. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Alva, Walter, and Christopher B. Donnan. 1993. Royal Tombs of Sipán. Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, University of California.

Cordy-Collins, Alana. 1992. “Archaism or Continuing Tradition: The Decapitator Theme in Cupisnique and Moche Iconography.” Latin American Antiquity 3 (3): 206-20.

King, Heidi. 2002. “Gold in Ancient America.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 59, no. 4 (Spring): 5-55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3269153.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds. 2017. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum and The Getty Research Institute. Cat. no. 19, p. 145.

Seo, Ji Mary. 2018. "How to Wear Body Ornaments from the Ancient Americas." In #MetKids Blog. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/metkids/2018/how-to-wear-body-ornaments-from-the-ancient-americas.

Artwork Details

- Title:Nose Ornament with Spiders

- Date:100 BCE–200 CE

- Geography:Peru, North Coast

- Culture:Salinar

- Medium:Gold

- Dimensions:H. 2 x W. 4 3/8 x D. 1/8 in. (5.1 x 11.1 x 0.3 cm)

- Classification:Metal-Ornaments

- Credit Line:The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

- Object Number:1979.206.1172

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Audio

1647. Nose ornament, Salinar artists

Luisa Vetter and Gabriel Prieto

LUISA VETTER (English translation): We are looking at a crescent-shaped nose-ring displaying four spiders.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK (NARRATOR): Luisa Vetter, an archaeologist specializing in ancient Andean metallurgy, describes how Salinar artists created this exquisite ornament.

LUISA VETTER (English translation): The spiders' bodies were cut from hammered gold sheet and their legs are made of gold threads. The spider's web is woven from gold threads crafted using a filigree technique. An artisan used heat to join these extremely delicate metal threads, welding them into a web.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Attached through the wearer’s pierced septum, the delicately fashioned spiders and web would hang in front of the wearer’s mouth.

Gabriel Prieto, University of Florida.

GABRIEL PRIETO: I think these gold adornments were used for special occasions and perhaps for daily use. Some of them are broken and there are some little cracks. So it suggests that those were constantly used.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: The Salinar era—when this object was made—was a turning point in Andean history when communities abandoned centuries-old religious traditions. The significance of the spider, however—with its ability to catch, kill, and collect prey—persisted.

GABRIEL PRIETO: The Salinar society is a very revolutionary time. This is a time when warfare emerged. So, social conflict and violence is present as well. It’s when the population increased. When there is a clear interaction between the coast and the highlands, but also between the coast and the Amazon rainforest. It's a very dynamic moment in Andean history.

JOSÉ MARÍA YAZPIK: Because the Salinar era lacked the monumental temples of previous centuries, some have described it as an era of slow social progression. Yet, discoveries of gold ornaments like this one in small villages, far from the typical centers of power, suggest that in fact important social changes were unfolding. These shifts in power laid the groundwork for the Moche culture to arise centuries later.

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.