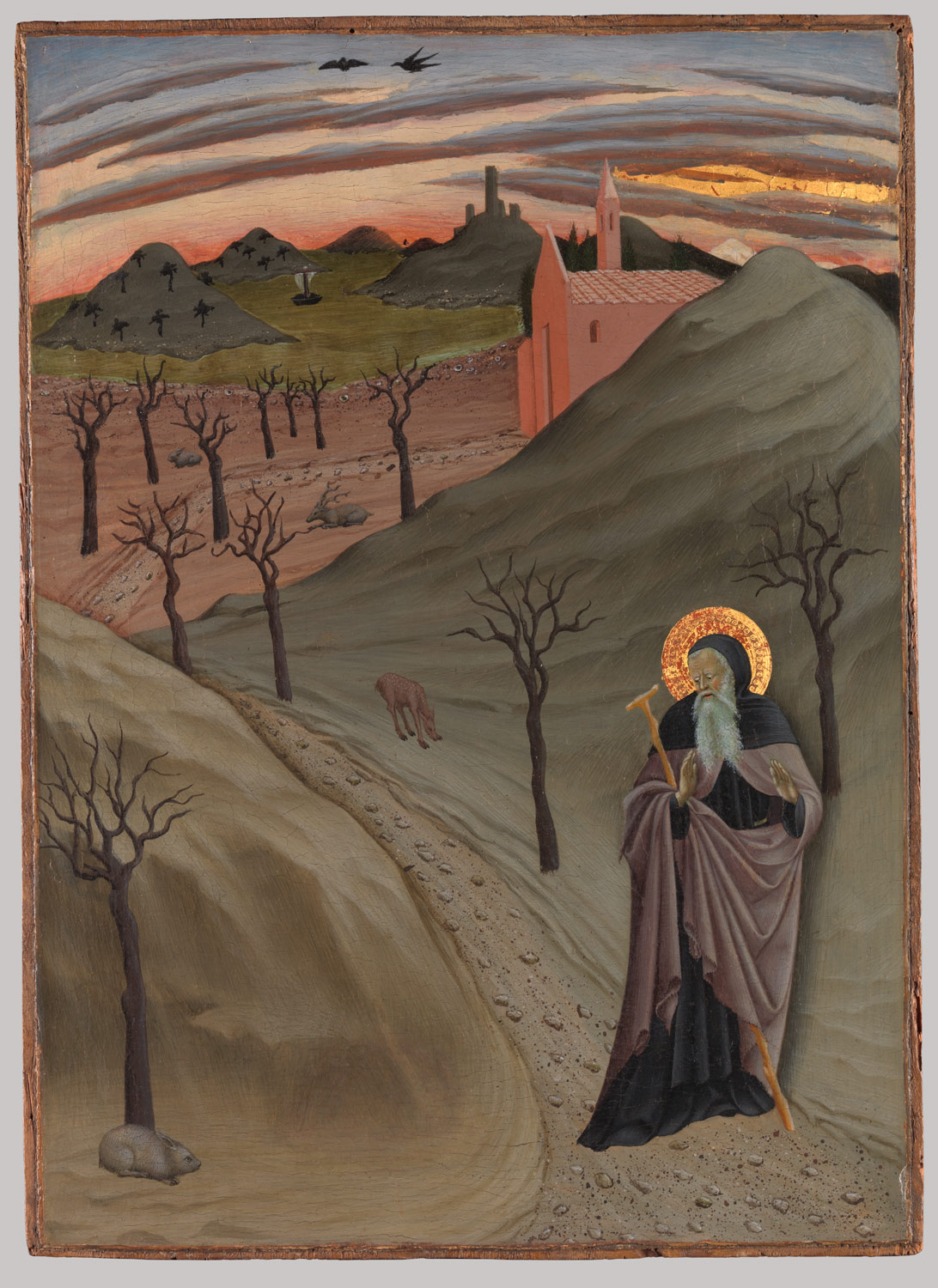

During this period, Italy—and in the fifteenth century, Florence above all—is the seat of an artistic, humanistic, technological, and scientific flowering known as the Renaissance. Founded primarily on the rediscovery of classical texts and artifacts, Renaissance culture looks to heroic ideals from antiquity and promotes the study of the liberal arts, centering largely upon the individual’s intellectual potential. As a result, tremendous innovations are made in the fields of mathematics, medicine, engineering, architecture, and the visual arts, while a surge of vernacular literature attempts not only to emulate, but also to surpass antique models. Some of the most celebrated figures of Renaissance Italy, supremely exemplified by the artist, scientist, and inventor Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), excel in several fields.

At this time, Florence is a hub of humanist scholarship and artistic production, due largely to the funding of the powerful Medici family, who, by the end of the period, exert their political and financial influence over much of central Italy. Significant urban development also occurs in Siena, an important artistic center, and the influential Montefeltro rulers of Urbino establish an illustrious court at which the liberal and visual arts flourish.