Matisse returned to Paris at the end of the summer with 15 paintings, 30 watercolors, and some 100 drawings. He saw this body of work as source material for his Paris practice. Over and above these tangible primers, the experience of Collioure would go a long way toward shaping his language in paint. The same was true for Derain.

When Woman with a Hat (1905) was shown at the Salon d’Automne in 1905, a juried exhibition of hundreds of contemporary artists, it ignited a furor. No one had ever seen color run wild nor raw brushwork announce itself on canvas with such flagrant disregard for its descriptive mandate.

The painting of Amélie, made in Paris soon after Matisse returned to his studio, boldly articulates the freewheeling experiments of that fabled summer. The picture is full of surprises and conundrums. Paint in all its glory seems to nearly suffocate the sitter.

One can hardly imagine wearing that hat.

It takes a lot of looking to realize that she is holding a fan spread across her chest, masking the rounding folds of her body. Red, green, pink, and blue alternate in often crude brushwork. Green takes charge everywhere.

Amélie posed for Matisse in his Paris studio wearing all black, save for a red ribbon around her neck. The painting becomes even more of a mystery, even more daring, when one realizes that its explosion of color was not real but imagined.

Referring to his Collioure paintings as shown in the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1905, Matisse said to his friend Signac some years later:

“It was the first time in my life that I was content to be exhibiting, for my things are perhaps not very important, but they have the merit of expressing in a very pure way my sensations. Something I have been working toward since I began to paint.”

The Collioure color experiments encouraged contemporary artists to look beyond the natural world in assembling their palettes.

Those who followed the example of Matisse and Derain were called Fauves. It was their daring new language that liberated artists to paint color from sensory experience. Fauvism was brief but vital to artists for decades to come as the strains of Modernism found new forms of expression.

Image Credits

André Derain (French, 1880–1954). Fishing Boats, Collioure, 1905. Oil on canvas, 32 × 39 in. (81 × 100 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Raymonde Paul, in memory of her brother, C. Michael Paul, and Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1982 (1982.179.29)

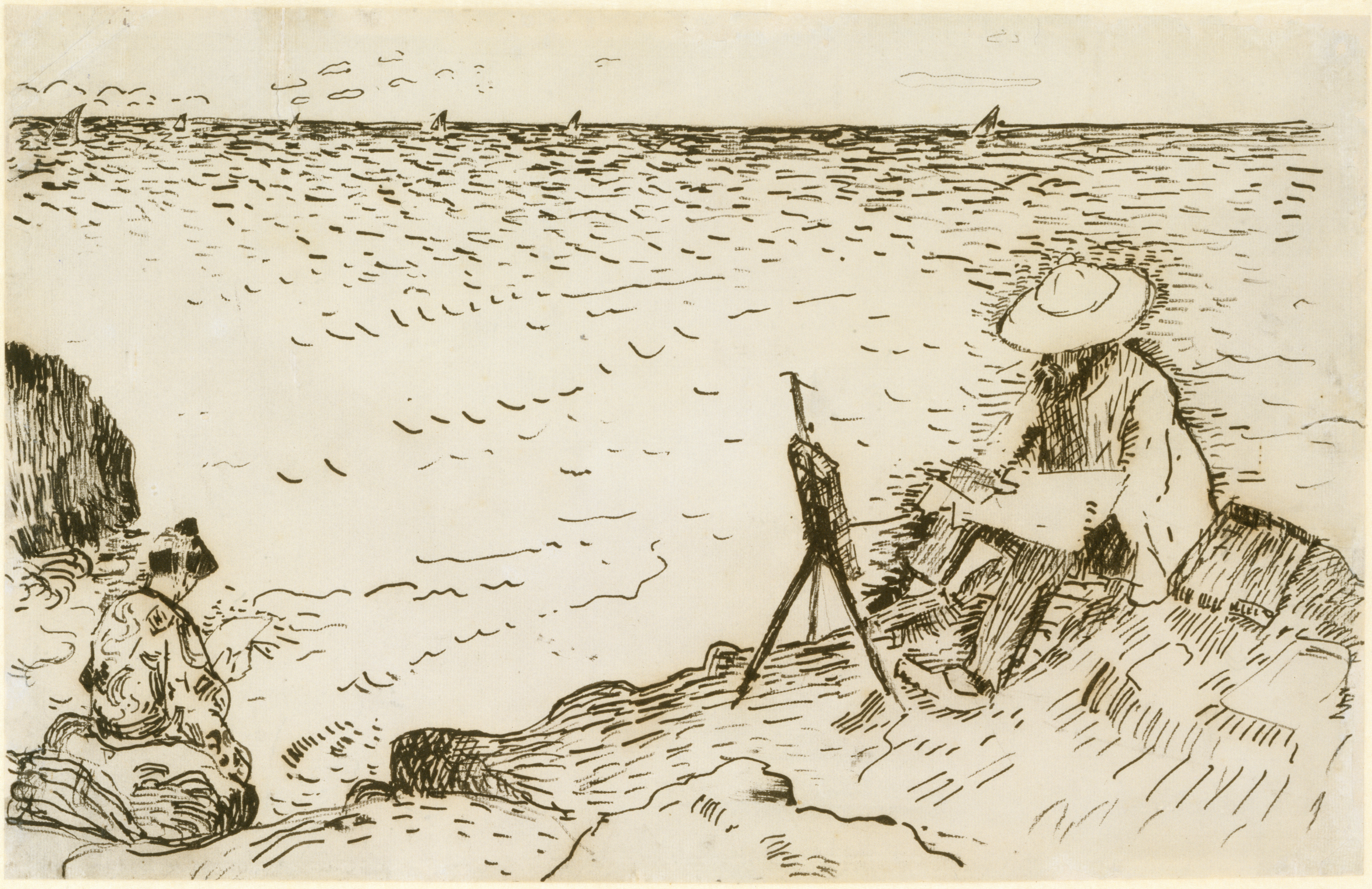

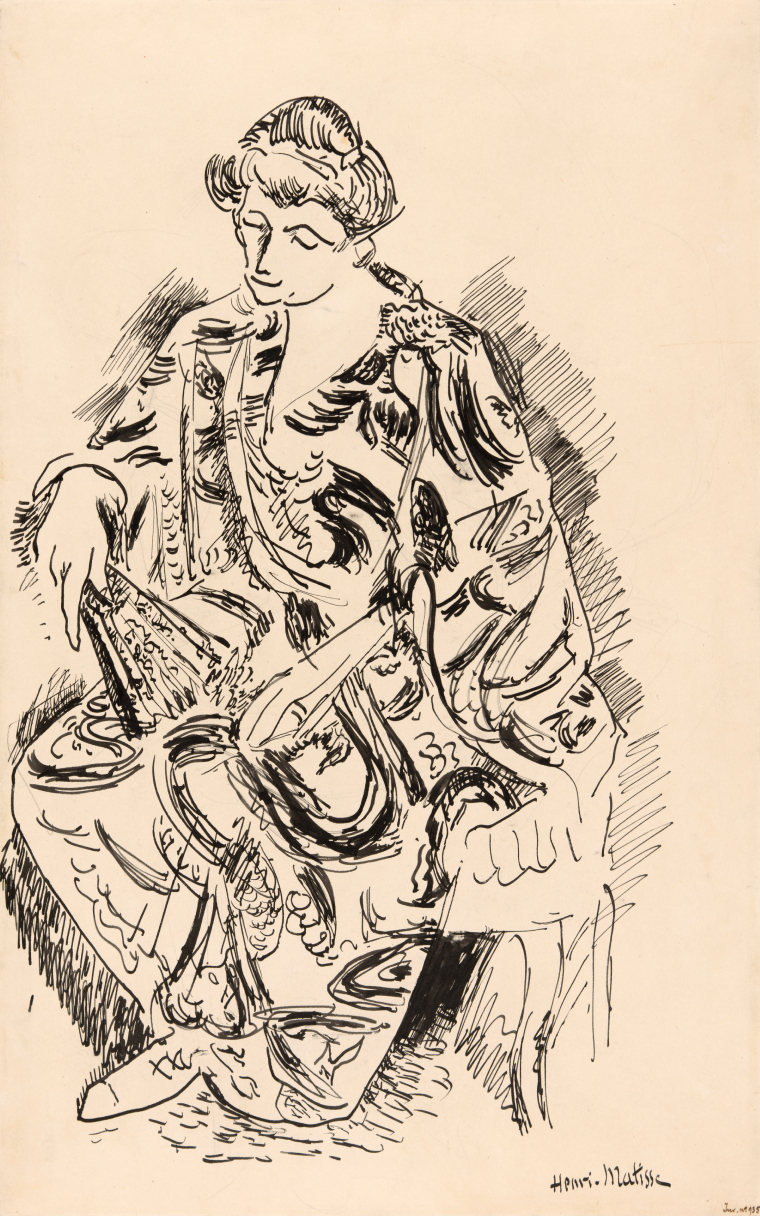

André Derain (French, 1880–1954). Matisse and His Wife at Collioure, 1905. Ink on paper, 12 × 19 in. (30× 48 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Hermina, Movses, Charles, and David Allen Devrishian Fund, 2004 (2004.60).

Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954). Woman with an Umbrella at the Seashore, 1905. Watercolor and charcoal on paper, 11 x 8 in. (27 x 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.6)

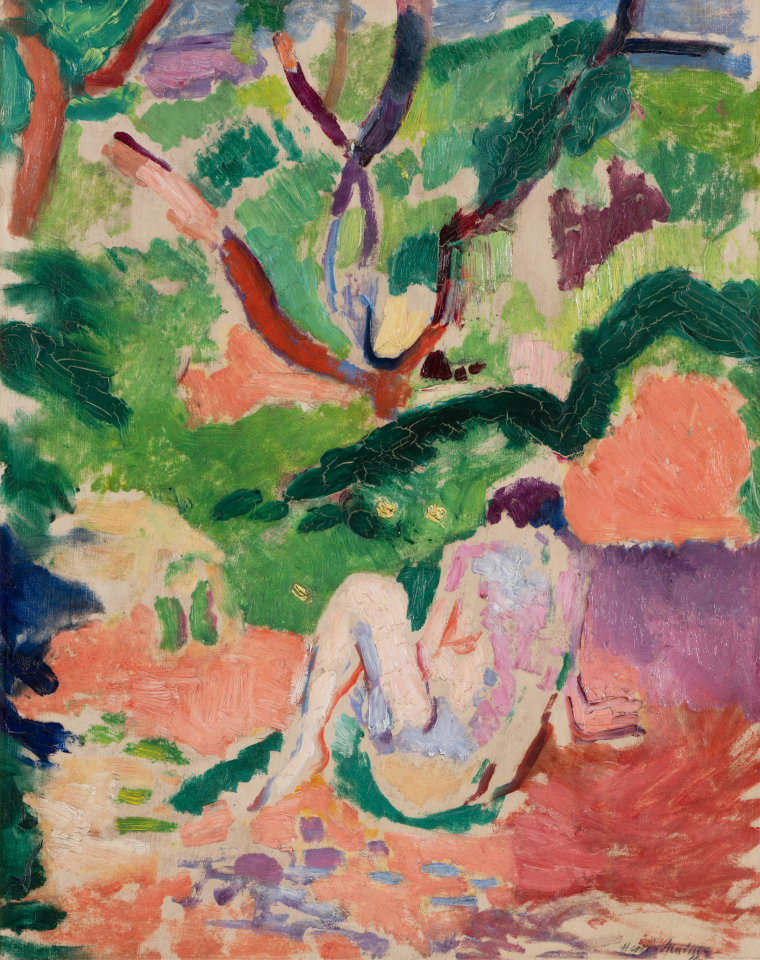

Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954). La Japonaise: Woman beside the Water (La Japonaise au bord de l’eau), 1905. Oil and graphite on canvas, 14× 11 in. (35 × 28 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase and anonymous gift, 1983 (709.1983). © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

André Derain (French, 1869–1954). Woman with a Shawl, Madame Matisse in a Kimono (La femme au chale, Madame Matisse en kimono), 1905. Oil on canvas, 32 × 26 in. (80× 65 cm). Private Collection, Courtesy of Nevill Keating Pictures. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954). Femme au chapeau (Woman with a Hat), 1905. Oil on canvas, 32 x 24 in. (81 x 60 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Bequest of Elise S. Haas. © 2024 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Ben Blackwell.