The artist Volker Hermes spends hours searching museum websites for his next subject. A society woman in a flamboyant headdress might catch his eye, or a princely young man trying too hard to impress. For the last decade, Hermes has used digital-imaging software to manipulate classic portraits from museum collections around the world. The result is his popular photocollage series Hidden Portraits. In these beguiling, enigmatic compositions, the decorative exacts its revenge on vanity. Ribbons and necklaces ensnare sitters like overgrown vines; public figures, keen to present themselves to the greatest advantage, are consumed by their own finery.

Hermes’s meticulously described collages pay homage to their sources while gently ribbing the social pretensions and ambitions of the courtly classes. His practice plays with the limits of perception and tenderly mocks human folly, whether it’s the desire to capture and tame the natural world or to flaunt the latest fashions.

I spoke with Hermes in his Düsseldorf studio, over Zoom. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

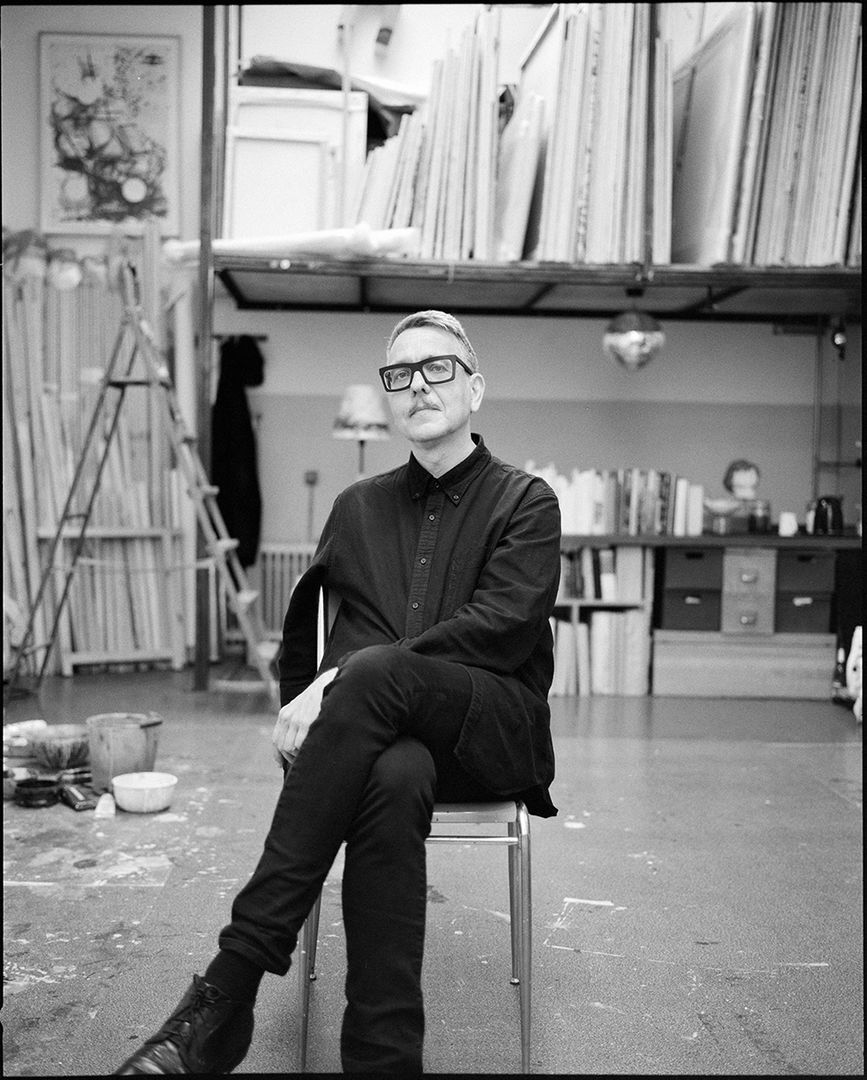

Volker Hermes in his studio. Photo by Franz Schuier

When did you start working on the Hidden Portraits series? Where did the idea come from?

It all started with a series of paintings in early 2008. I painted portraits of friends, covered them with a lot of fabrics and hats. I wanted to find out what a portrait really portrays. Does it need a face? Or can you recognize your friends without their faces, by their habits and gestures? Around this time, I also started to experiment with Photoshop. But I never showed these experiments to anyone. Because first of all, I’m a painter, and I recognized that people are confused that I’m making these works. Which surprises me a bit, because I consider my digital works to be very painterly. The whole project is about paintings but the works are just made using a different technique, the way etching is a different technique.

In my opinion, making art is always a process of developing your own language with new materials. When I first decided that I wanted to work with image editing, for example, I had no clue how to begin. I’d heard of Photoshop, of course, but never worked with it. So I decided to teach myself how to use it. I was educated at the Düsseldorf Academy, which is more of a traditional art school. And this traditional approach means: We can’t teach you everything. Do you need a new technique? Learn it! If you have internalized that way of thinking, you feel a kind of freedom to conquer even the most complicated new things.

“I wanted to find out what a portrait really portrays. Does it need a face?”

Most of the art I made at school was about my friends and our private lives. This was Germany in the ’90s, after the Berlin Wall was torn down, during the early days of electronic music—a rather hedonistic time. We were always dancing. That’s why I had very little background in art history. It was only after graduating, as I was trying to find my own language as a young artist, that I began to think about my roots—about all of these people who had painted before me. I dove into the world of painting. I wanted to understand more deeply the connection between artists and society. Why were these portraits commissioned? Why did the artists paint them this particular way?

At first I only looked at the faces, as I think everyone does at the beginning. But I started to read more about the system of portraiture and realized that there was so much information I was ignoring by only thinking about the faces. There’s so much going on in these paintings beyond the figure. Now I recognize the vocabulary used in many of these paintings, even if it’s not the vocabulary we use today. One of the most basic decisions I made from the start was that I didn’t want to paint these portraits, I didn’t want to imitate them. But I was also very curious: What happens if we can’t see the faces anymore? What tools could I use? Image editing, I felt, was the best way forward because I could work with these portraits without painting them again. That became my new approach.

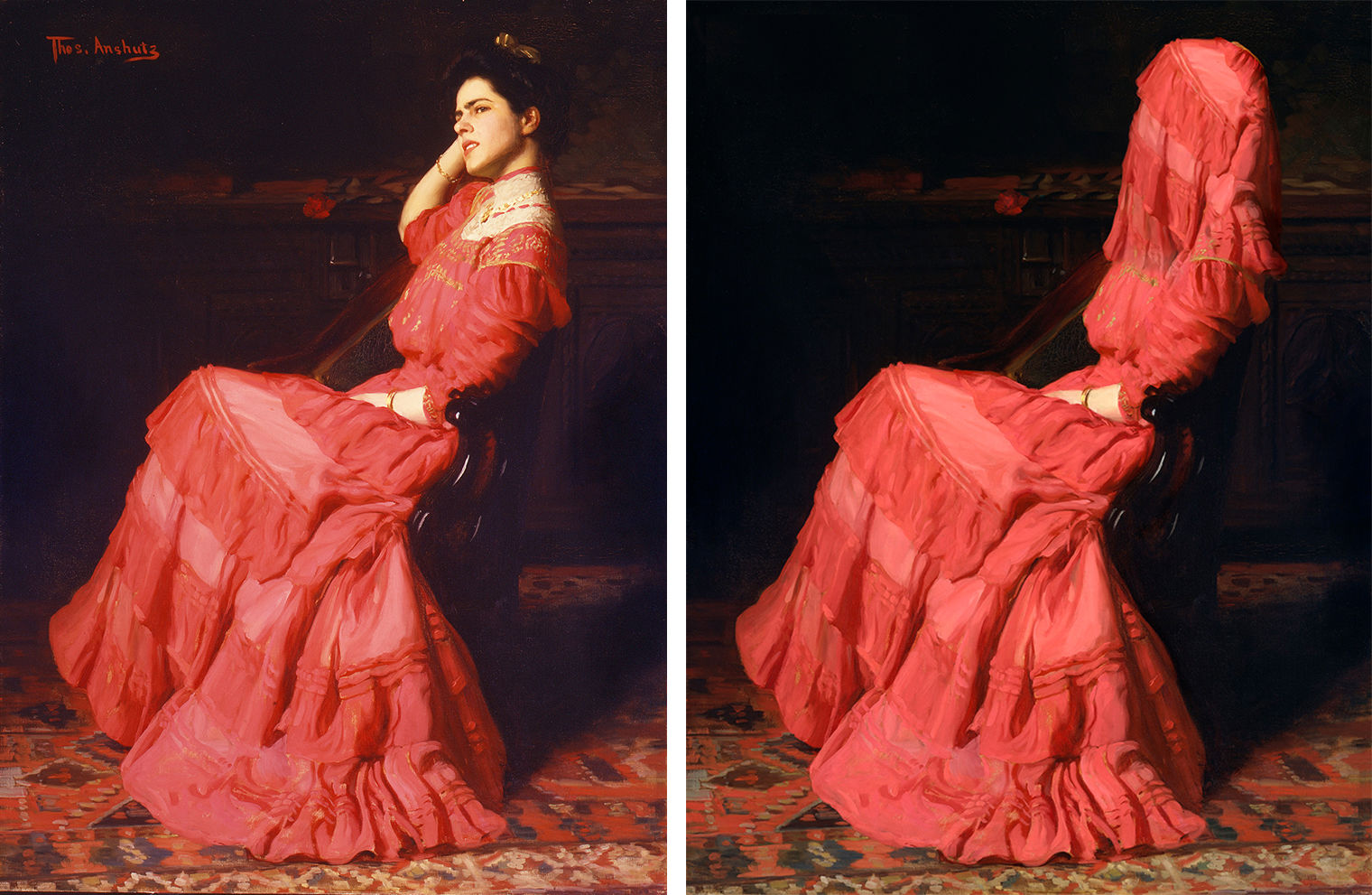

Left: Thomas Anshutz (American, 1851–1912). A Rose, 1907. Oil on canvas, 58 x 43 7/8 in. (147.3 x 111.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 1993 (1993.324). Right: Volker Hermes. Hidden Anshutz, 2019. Photocollage © Volker Hermes

I’m absolutely convinced that we have to accept digital forms as an additional technique for our lives and for art. This kind of hierarchy or ranking between the techniques is something I never had. You can use whatever is necessary to create art—whether you use a pen or a brush or a computer mouse. So I jumped into the world of image editing and the first image I was satisfied with was a portrait of Cardinal Richelieu. He was clearly so powerful and so important, and it was a really flashy work. I covered him with his robe. This work sat quietly in my studio for a while and the first time I showed it was in 2015.

There was a seven-year gestation period where you were doing this work, not showing it to many people. Then, suddenly, it’s out there. Why did you first start showing these works, and how were they initially received?

Well, I’d made very, very small prints—like when you go to the grocery store and ask them to print photos from your mobile phone! But the first time I showed them, in 2015, it was on the website of the Rijksmuseum. They have this open platform where you can start a profile and respond to artworks in the collection. I was quite nervous, because these works were so different from my own paintings. Of course, at first nothing happened.

In the late summer of 2019, a friend of mine persuaded me to get on Instagram. She told me that everyone was there and I replied: Gosh, Instagram! This is the end of the world! But let’s give it a try. I uploaded some of my works. Again, for a while nothing happened. Then somebody shared my posts, and from one moment to another I had five hundred followers, and then a thousand. I had no idea how to use Instagram to be honest. I’d never written a DM before and suddenly people from museums were reaching out out. Magazines asked to interview me. The first was with a magazine from Chile. It was wonderful! I’m very grateful that people have responded well to my art. Especially because at first I wasn’t sure whether I should show the Hidden Portraits at all. But they are amazingly important to me. They are my thoughts, my friends. To see that so many people appreciate them is still a kind of wonder.

Volker Hermes. Hidden de Champaigne, 2009 (edited 2022). Photocollage © Volker Hermes

There came a point, of course, when I had to think producing my collages. I’m not a photographer, so I didn’t know much about the technical aspects of printing. But I knew quite well what they should look like in the end. Fortunately, in Düsseldorf, there are a lot of famous photographers like Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, and many others, so we have good infrastructure for this type of work. I found workshops that were kind enough to explain everything to me. It was a longer process to find the right paper, the right kind of frame. But after working on these on my computer for the last ten years, I finally got involved on the production side. That felt good.

How do you decide which paintings to manipulate? You’re making a significant time commitment when you choose one, since your practice involves a good amount of research as well.

It’s very intuitive. I research a lot. Almost every day I’m browsing open access collections on museum websites. The selection process is determined by personal moods. Sometimes it’s just a person’s face, you know—though I have certain preferences. At times, Baroque portraits with their sumptuous forms appeal to me more than the more reduced, austere Renaissance variant. But sometimes it’s the other way around. I have a big stock of images that I’ve compiled over the years, hundreds of images that I’ve started to work on. I’ll start on one and maybe it’s not the right time. But I return to it occasionally, working and reworking it until it’s finished.

It depends on what the portraits say to me. I have to see some kind of possibility in them. I’m not interested only in the major portraits from art history. I'm not working with Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa or Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring. (They have suffered enough from Photoshop manipulations.) It’s more about what a specific image can tell me. I’m really compelled by works that speak to me about why portraits were painted. Even when the painter or subject is not so famous, they are so significant for what they can tell you about a certain time or place, or for the way they record a sensibility or even a kind of artifice.

I love your handling of Jacometto’s Portrait of a Young Man (1480s), which was recently featured on the cover of The New York Review of Books. The way you’ve elongated the hair so it’s almost like armor is humorous and bold, but it also draws attention to the rich painterly description in the original work. What drew you to this painting?

It's a really striking work, because it takes this sculptural approach to the hair. It’s very simple, in a way—it’s so strong, this reduction of the details. Gold and diamonds aren’t the only things that convey social rank. This haircut, for example, was very famous for a short period. But we have a lot of portraits featuring it. You can imagine that in the 1480s only young men from aristocratic backgrounds were able to choose such a fashionable but also very difficult haircut.

Left: Jacometto (Jacometto Veneziano) (Italian, ca. 1472–before 1498). Portrait of a Young Man, 1480s. Oil on wood, 11 x 8 1/4 in. (27.9 x 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949 (49.7.3). Right: Volker Hermes. Hidden Jacometto, 2019. Photocollage © Volker Hermes

Because his gaze is so dominant in this portrait, I decided to bring down the hair. It was a funny moment for me. Without the sitter’s eyes, you pay more attention to the surface of the hair. Usually you’re distracted by the eyes. Now you realize how the hair is painted—all of the amazing work and attention that went into painting it. And you recognize the social relevance of a haircut. I use humor as a kind of intervention, to make a message from the past more easily accessible without being too didactic. You can point out a lot of things with humor because it is so direct. I love that.

How long does it take for you to make one of these portraits? Some works, like the Jacometto, are perhaps more straightforward. But in your reinterpretation of Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s Comtesse de la Châtre (Marie Charlotte Louise Perrette Aglaé Bontemps, 1762–1848) (1789), you took the ribbon from her hat and wrapped it around her face, obscuring nearly all of her features except for her nose.

Each one is quite different. The Jacometto didn’t take so much time because it was only the act of pulling down the hair. But there are other works where I have to redecorate with jewelry or ribbons, or I’m adapting a single pearl to create new necklaces. This can take one or two weeks of constant detail work. Sometimes I have to stop and put them away for a while to avoid losing track or getting lost in details.

What definitely helps is that I’m a painter, and I know how to represent reality in painting. When I’ve wrapped fabric around the body, of course, the back has to look different from the front. And I know how I can achieve certain effects—how this fabric will look when there’s not so much light in the background. Looking intensively at the paintings is very important for me. I’m zooming into these works so I can see the tricks these artists used, especially with pearls. Sometimes an artist had to paint two hundred pearls, and you see in some parts how fast they worked, and how skilled they were. This is always very touching, because it makes me feel close to my colleagues from the past.

Left: Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Comtesse de la Châtre (Marie Charlotte Louise Perrette Algaé Bontemps, 1762–1848), 1789. Oil on canvas, 45 x 34 1/2 in. (114.3 x 87.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Jessie Woolworth Donahue, 1954 (54.182). Right: Volker Hermes. Hidden Vigée Le Brun, 2019. Photocollage © Volker Hermes

Fortunately, years ago I worked in a workshop for historical opera costumes. I was just working there in the office, but around me there were all these extraordinary costumes. At one point I stepped out of my office and started to ask questions: What is this? Why was it made this way, and how? I asked about different cuts and fabrics and learned why certain things are constructed the way they are. All of this really helps me when I’m working on my collages. It helps make everything plausible. The original painter had these dresses in front of them. I have to imagine.

I read that you don't add elements to these paintings—for example, you're not interested in placing an iPhone in someone's hands. I'm curious to know how you make rules for yourself, and if there are others you’ve established over the past decade of working on this series?

There were some basic decisions I made right at the beginning: I don't want to add anything from “outside” the painting, out of respect for the artists and for the works of art. Parts of my work sometimes seem rude, because I really do change some significant aspects. But the painting belongs to itself. The original spirit and dignity must not be lost; I love these paintings far too much for that. I try to have a discussion with the painting, and use only elements already contained within the painting. I have quite a long list of rules that I made for myself. For example, I'm not coloring anything, I'm only adjusting lights. The original artists made their choice of colors—who am I to change that? I prefer to modify other things.

Are there specific poses, gestures, or styles that you've come to love over the years of looking at all of these different portraits?

Yes, I really like the extremes. You have these over-the-top poses in portraits meant to display male power, since these societies were often entirely male-dominated. And you can definitely see that in the portraits. Their postures are so proud and the portraits are so overdone. This is, of course, a very friendly invitation for me. When you create a ridiculous hat and put it on this vain figure, the whole visual system of status symbols collapses.

“When you create a ridiculous hat and put it on this vain figure, the whole visual system of status symbols collapses.”

On the other hand, in a work like the Vigée Le Brun, the comtesse is almost lying on this couch because she wants to be depicted in an informal style, in her white dress, which was very fashionable at that time. It was not French silk; it was cotton. This was a fashion popularized by Marie Antoinette. So she's showing herself in the poshest way she can: relaxed and reading a book, to signal that she’s well educated. There are also many paintings of this kind of woman sitting in gardens. They dress up like they’re going to a ball, but they're just sitting in their gardens! It’s not by accident: they want to convey something with these surroundings. The garden is not just a backdrop—in some ways, it is the ultimate accessory. You live in this Edenic splendor that is so carefully maintained, which means that you have a staff that is likely doing it. You’re probably not out there with your shears pruning your perfect hedge.

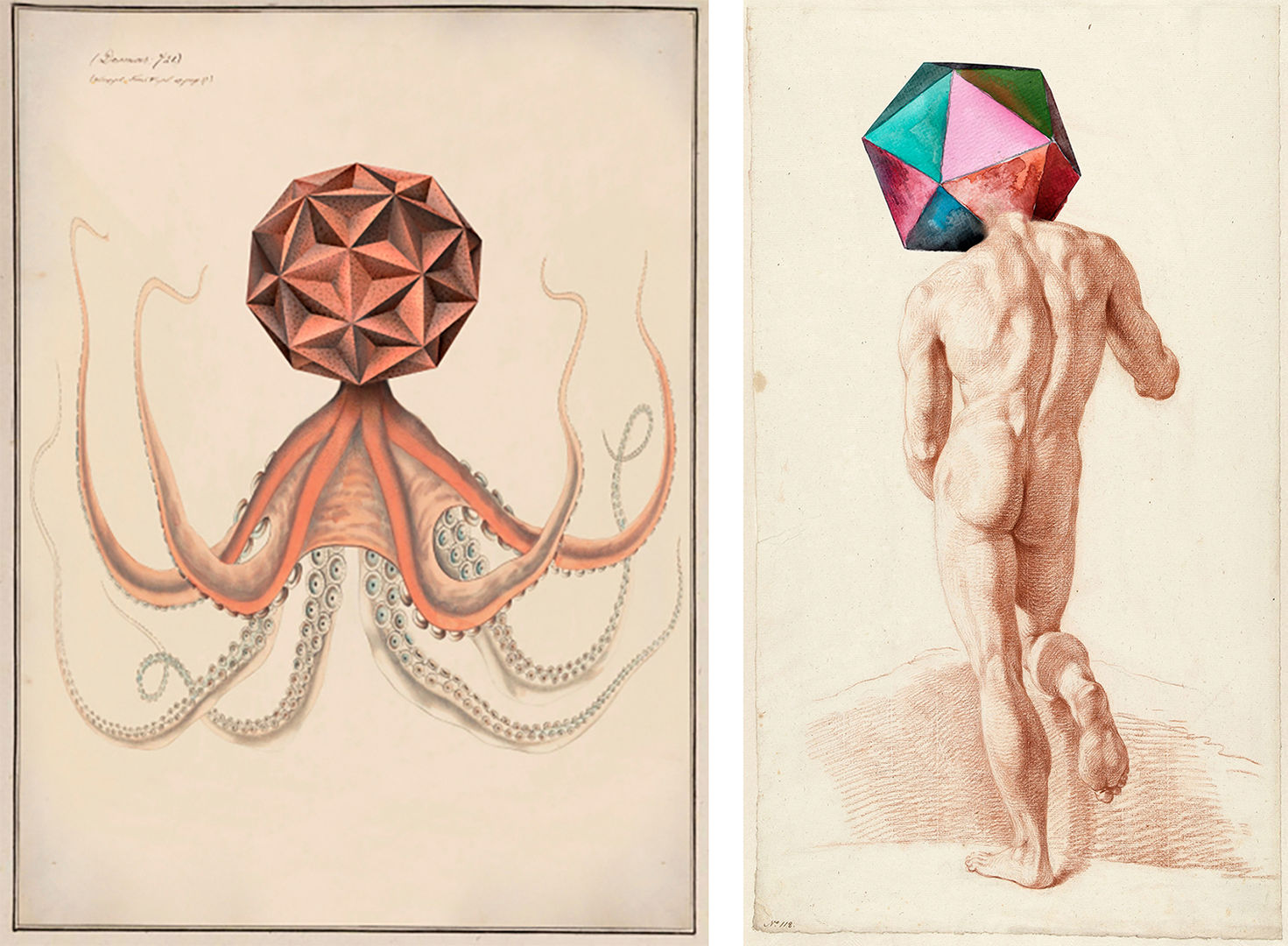

The Hidden Portraits are among your most well-known works, but you also have other series that combine polyhedral forms with natural-history illustrations and academic studies. Could you tell me more about these?

Over the last thirty years I have worked on a number of series that all revisit historical art from a contemporary perspective. I am interested in combing different worlds through collage. For example, culturally and historically important works such as natural-history drawings or academic studies of the human figure—which are all too often seen as auxiliary constructions by artists, rather than art in their own right—are combined in my work with mathematical forms that illustrate eternal principles.

Left: Volker Hermes. Animalis Polyedae XV. NFT. Right: Volker Hermes. Academic Studies XV. NFT. © Volker Hermes

You’re also interested in historical-battle paintings and seascapes. As with the portraits of male power, I’m aware that your goal isn’t to glorify these scenes but rather to deconstruct some of these visual tropes and point out their absurdities. Could you tell us what you're working on right now?

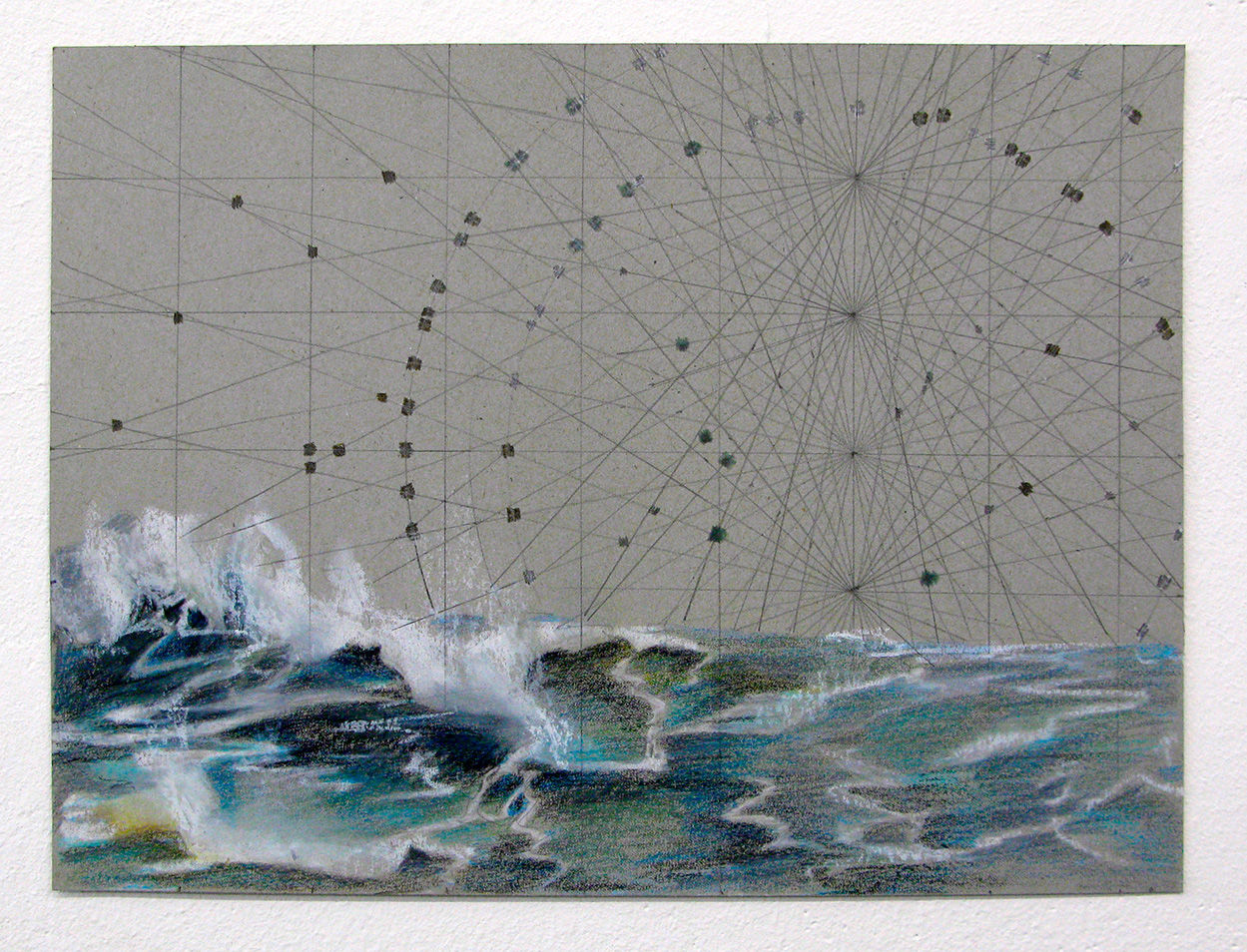

For years, I have translated painted seascapes and sea battles into drawings. I used various gravity markers and black tagging markers on canvas. These markers are immediately permanent and cannot be corrected. Every stroke is a statement and you have to use them quickly and very directly. This allowed me to capture the incredible energy of these seascapes that were so important to societies at the time. The whole space of the sea was synonymous with the space of invention. All these expeditions, all these ship-building techniques were essential for the further development of the world. And so many wars were decided on the sea.

Volker Hermes. Untitled, 2012. Pencil, pastel on gray paper, 9 3/4 x 13 1/2 in. (25 x 34 cm). © Volker Hermes

Additionally, I was interested in battle paintings because they were documentation of something that happened far away from the shore, often without artists to witness them. These battle scenes, of course, were very chaotic in real life, but the paintings were made afterward, in the calm of a studio. Nevertheless, with their many different dynamic elements—the waves, the clouds, the masts, and the ships—they transport the whole existential situation onto the water.

These projects have a common thread, which is the narrative of the world seen through the eyes of artists. From historical expeditions where artists saw certain parts of the natural world for the first time to maps and battles. Similar to the academic studies, maps and sketches are actually quite beautiful drawings in their own right, too. They are inventions, in a way. And invention is for me one of the basic tasks of an artist. You’re putting something new into this world by mixing your own skills with existing materials, and this act of combination brings a new aspect of the world into being.