The First Tourists

I grew up in American Samoa. When the Americans came in World War II, they outnumbered everyone two or three to one. The island was full of tanks, they practiced war games, and all the trees were smashed down. Even in the 1960s, the young women in my village were topless because of the heat. Men in Samoan society did not view this as a sign of enticement; it was practical. When the Americans came, the soldiers thought it was an invitation and there were problems all over the island. A law was passed where the women had to cover themselves. So the women had to cover themselves for the American men, not for themselves.

Rosanna Raymond and Dan Taulapapa McMullin, Aue Away, 2017, activations for Tiki Talks in Central Park. Image courtesy Dan Taluapapa McMullin

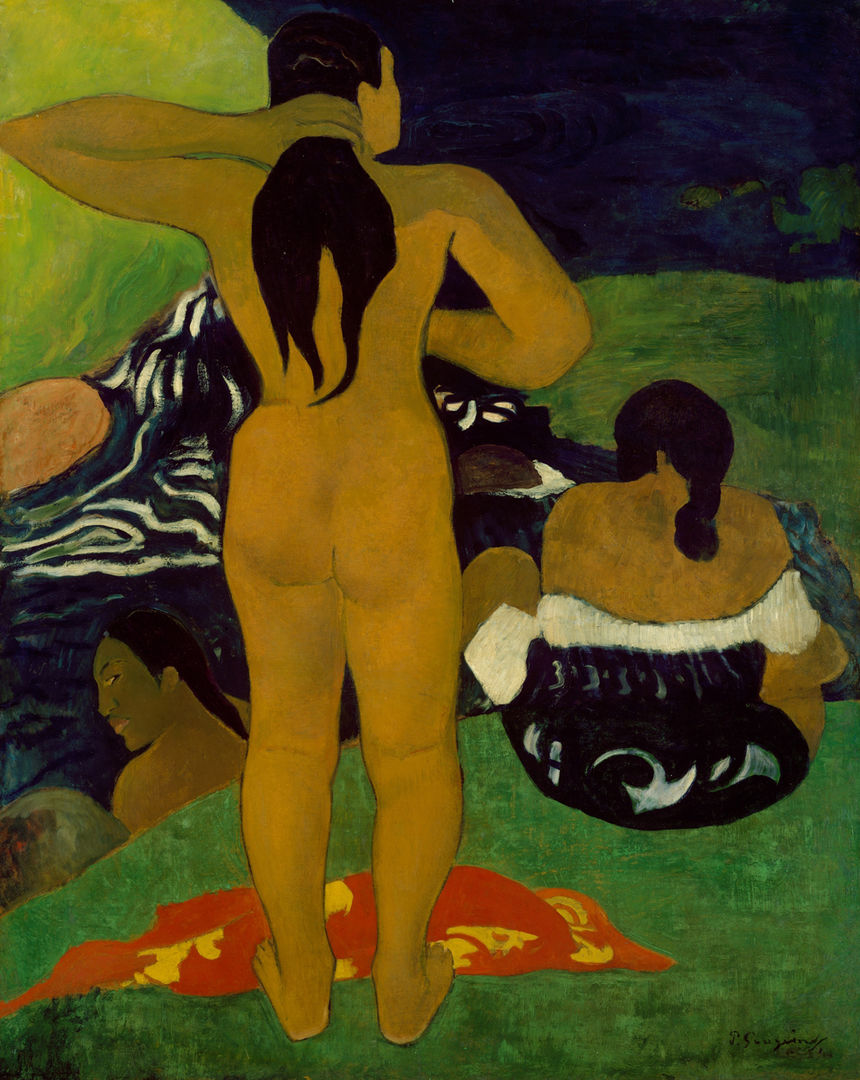

This idea of covering the body is reflected in a performance piece Aue Away I did for The Met with the Samoan artist Rosanna Raymond. This notion of playing with Tiki ideas of Pacific Islander and Polynesian culture was part of my critique. For this performance piece, Rosanna and I walked very slowly through the Museum, dressed in these bodysuits I had fabricated, completely covered in flowers and leaves. We visited works in the collection, including various paintings by John La Farge and Paul Gauguin. La Farge arrived in Sāmoa in 1890 and Gauguin went to Tahiti in 1891. The Met has a very beautiful watercolor by John La Farge of Samoan women carrying a canoe. And of course, it has several great paintings by Paul Gauguin of Polynesian women in Tahiti.

John La Farge (American, 1835–1910). Girls Carrying a Canoe, Vaiala in Samoa, 1891. Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on off-white wove paper, 17 15/16 x 21 7/8 in. (45.6 x 55.6 cm). Purchase, Mrs. Arthur Hays Sulzberger Gift, in memory of Mr. Arthur Hays Sulzberger, 1970 (1970.120)

Again, I’m conscious of the Western patriarchal gaze, exploiting the colonial position of Tahitian women in relation to Frenchmen. Gauguin looked different from the other Frenchmen they had met. He dressed differently. He had long hair. In some ways, La Farge and Gauguin were the first tourists. They were the first non-missionary, non-military, non-explorer Europeans and Americans to come to a romantic idea of Polynesia in the Pacific Islands.

“Tiki Manifesto” by Dan Taulapapa McMullin

This tourism led to further colonialism, exploitation, and disease. Eighty to ninety percent of the local population died from European and American diseases that were introduced when Europeans first arrived to the islands. This significant population decrease enabled Europeans to build sugar plantations, bring indentured workers from other countries, and establish colonies in French Polynesia and the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, which was overthrown in 1893 and later became the U.S. territory of Hawaiʻi. My country, American Samoa—also called Sāmoa 'i Sasa'e or Eastern Samoa—was divided in 1899 between the U.S. and Germany into American Samoa and German Samoa.

Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903). Tahitian Women Bathing, 1892. Oil on paper, laid down on canvas, 43 3/4 x 35 1/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.179)

When I visit objects in the Oceanic galleries, I communicate with my own personal history. When I view the works of Europeans and Americans who visited Polynesia I try to establish a relationship with the people in the work. I recognize their faces. It’s the faces of my mother, my women friends, my male friends, my lovers. My colleagues are all reflected in the faces I see in these paintings. I see their bodies. I see their actions.

The Survival of Takatāpui Mythologies

The sculpture of the Pacific Islands can be very abstract. Our people were all sailing peoples. They were involved in long voyages in the ocean for fishing, trade, war. There was constant traffic and exchange of cultures, language, and goods. In Papua, the largest island of the Pacific islands, there are ancient cultures that have been there for tens of thousands of years. These sculptures were often created for specific moments—initiations, deaths, or marriages— and then destroyed or brought back to nourish the forest.

Bis Poles. Asmat people, late 1950s. Indonesia, Papua Province. Wood, paint, fiber, 18 ft. × 39 in. × 63 in. (548.6 × 99.1 × 160 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1611)

Bis poles, for instance, were created to commemorate war, initiation into warrior status, or deaths within a family. Multiple deaths correspond to multiple figures on the pole, which included totemic spirits in the form of animals, plants, and fruits. It was believed that they provided spiritual sustenance for ancestors. What I love about the bis poles is there’s nothing else like them that I know of in art—although, in a way, they are like the totem poles of the Pacific Northwest. They are ancestors, one atop the other, creating what is frankly a phallic symbol. The phallus is both a male and a female symbol, representing connection and fertility. In Samoan we call this ola or siola, which means the material of life: sperm, the phallus. You see it at the top of the pole in the jet that goes out into the air. When the pole has been used in the ceremony, the poles are taken again to the forest and returned to this place of fecundity. In a similar sense, Samoan culture recognizes the nonbinary position as a sacred position in healing.

"Atea" by Dan Taulapapa McMullin

The Met has several magnificent examples of Maori flutes, or pūtōrino, that invoke this male and female principle. The putorino relates to the Polynesian myth of Tiki Tutanekai and Hinemoa, which Māori writer and queer activist Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku identified as a very important story in queer history. In the story, Tiki and Tutanekai are two young chiefs and male lovers. At night they play flutes on a lake. Tutanekai plays the putorino. When the young woman Hinemoa hears the flutes, she falls in love with Tiki before she ever sees him and they become lovers. Since Tutanekai lost his lover, they find him a young woman. Tiki and Tutanekai become young men in this transition. They’re not transgender and they’re not men who live as women. They’re young men who were lovers and who, together, find these young women.

Flute (Putorino), ca. 1800–20. Maori people. Wood, fiber, H. 17 × W. 1 1/2 × D. 1 in. (43.2 × 3.8 × 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1599)

Many Europeans recorded these stories but the translations changed and that’s how these stories survived. The Maori term Takatāpui means “to cross” and historically refers to intimate companions of the same sex. The word hoa means “friend.” Gray, the English governor of New Zealand who collected these stories, ignored the takatāpui aspect in Aotearoa-New Zealand. The nonbinary translation of the word was ignored so in “hoa takatāpui,” the meaning changed to mean “a friend.” The Europeans may have known the original meaning in private, but their writings eliminated the erotic connotation. These stories were from what we call the Pouliuli, or the dark past. Often these stories only survived if they were published by colonial authorities or Hawaiian-language newspapers.

Kanaka Maoli or Native Hawaiian historians like Lilikalā Kame’eleihiwa and Noelani Arista who work in the Hawaiian language—and Samoan philosopher historians like Tui Atua Tamasese, writers embedded in Indigenous languages—have a basic understanding of whats going on in Pacific Islander history. Knowledge of these theological aspects can only come through a knowledge of language. Without a basic knowledge of language, there is no gateway into the meanings of these stories.

Seiana: A Triptych

I first grew up in Europe. My father was in the military and when he went to Vietnam, my mother took us to Samoa. There was a dirt road in the middle of a rainforest. It was a complete culture shock. When we arrived, the entire village was decorated with flowers. The pillars of the church were covered with vines, everyone was covered in flowers, and they were dancing for us. I'll never forget this introduction to Samoa and my culture. I was about five years old and had spent my early years in Japan and Germany. And then there I was, immersed in Samoan culture and immersed in flowers.

Left panel of the triptych Seiana. Image courtesy Dan Taluapapa McMullin

In a triptych for the Hawaiʻi Triennial in 2022, I wanted to pay homage to the Indigenous and Black movements that influenced me. Sei is the flower that you wear in your ear whenever you go out to meet family, a lover, or a friend. Seiana, which is also the name of the triptych, is the act of decorating oneself with flowers.

The first painting in the triptych is an homage to West Papua. In it, I’ve depicted Benny Wenda, the exiled leader of the West Papua Independence Movement. His family was murdered when he was a child and they had to flee West Papua when Indonesia took over. To his left is the figure of Victor Yeimo, who was immediately imprisoned by the Indonesian military when he held up this sign during a protest. In English, it says, “I am not a monkey.” A leader of the Indonesian government called the West Papuans monkeys and used this term to justify their murder.

Middle panel of the triptych Seiana. Image courtesy Dan Taluapapa McMullin

The middle painting in the triptych pays homage to the Kanaka Maoli Native Hawaiian movement. On the left, you see the leaders of the Hawaiian movement of the ’70s to the ’90s: Lilikalā Kame'eleihiwa, the historian of the Great Mahele and translator of Hawaiian chants; the Hawaiian poet Haunani-Kay Trask. On the right, you see Martin Luther King. King went to seminary with the Hawaiian minister Reverend Akaka. Reverend Akaka invited King to Hawaiʻi to speak about the African-American movement against racism. Likewise, Reverend Akaka sent a Hawaiian delegation to some of the Alabama Selma marches in the ’60s. You see King wearing Hawaiian lei because of this very close connection to the Hawaiian movement.

Right panel of the triptych Seiana. Image courtesy Dan Taluapapa McMullin

In the third painting in the triptych we go further into the past, into the ’40s and the ’60s. Bikini is the Micronesian island that was bombed in a test by the U.S. Navy in 1946. The Bikini Islanders were relocated forcibly. You see Bikini women carrying their world on their shoulders. This is really the last day that they spent in their homeland. There was a movement two decades later to return, but the radiation was so strong from these atomic tests that they couldn’t live there. On the left is the Tahitian poet Henry Hiro blowing a conch shell and calling up the ancestors. He was a poet and activist in the anti-nuclear movement. So you see the two great struggles in Bikini Atoll and in Tahiti, against nuclear testing by the Americans in Micronesia and testing by the French in French Polynesia.

When the naval government came to bomb Bikini Island they engaged top-notch Hollywood photographers and filmmakers to paint a pretty picture. They got rid of the Bikini Islanders and threw a big party. For months they partied on the island and then they blew it up. There’s a famous photo of the naval commander who bombed the island cutting into a cake that looks like an atomic cloud in Washington, D.C. For the Americans, it was a celebration of American power; for the Bikinis, it was a complete devastation of their culture. To this day, they’ve never been able to return to that island. There are several domes that actually cover the nuclear waste. The United States didn’t need to use this island. They had many, many uninhabited islands. So why did they use this island?

Colorized work of the photograph Admiral Cuts 'Atomic' Cake from Nov. 5, 1946, 3264. Image courtesy Dan Taluapapa McMullin

After the explosion, the Bikini Islanders who were forced to leave, but also the people in the surrounding islands, were medically researched. Their bodies became part of the research to see if Americans could survive atomic explosions. But American bodies were not used in this medical research.

There are so few images of these movements in institutional spaces, perhaps because they’re seen as too political. But these are artistic movements: movements of people engaging in language, movements of the arts and of survival. These artists are like canaries in a mine and are often the first voices to be silenced. In that sense, the voices of artists are integral to the museum. It’s the voices of Indigenous artists like Henri Hiro, Benny Wenda, and Haunani-Kay Trask that we don’t see in contemporary museum spaces in the West. We have to see them because these are the voices of Pacific Islander, Polynesian, Melanesian, and Micronesian artists. These are our voices and if they are not in the contemporary institutions, then our history is not in the contemporary institutions. Our bodies would not be in the contemporary institutions because we will not see ourselves here.

“Anointed” by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner

Voices of Polynesians and other Pacific Islanders are the voices of our songs, in our dance. But for us, the part that is lacking in Western institutions is the meaning of these songs. The only key to the meaning is through the language. Part of our struggle as artists is to bring those meanings back into the conversation. That’s what we hope to bring back to the institution, our contemporary images and poetry.

Further Reading

Dan Taulapapa McMullin. Coconut Milk. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 2013.

Dan Taulapapa McMullin, The Healer’s Wound: A Queer Theirstory of Polynesia, Tropic Editions and Puʻuhonua Society, 2022.

Melissa Chiu, Miwako Tezuka, and Drew Kahuʻāina Broderick. Pacific Century — E Hoʻomau No Moananuiākea: Hawaiʻi Triennial 2022. Honolulu, Hawaiʻi: Hawaiʻi Contemporary, 2022.