The clay we shaped as children waited on the art room’s tables when my class arrived for our annual pottery unit. Soft blocks the size of our third-grade heads, wrapped in plastic film to retain moisture. The word drab describes a specific color, “a dull light brown” (OED). The clay I worked with as a child was drab. I never really threw a pot. I wouldn’t even call what I did working with clay. Instead, I assembled crude objects. I was lucky to have parents to go home to at the end of the day who would smile and kiss my forehead when I handed them the ugly little oddities I made with my own hands.

I remember how the clay oozed between my fingers as I pulled it from the cool block. Resistant at first, then growing more pliable as it warmed. Soon I could roll lumpy clay noodles and spiral these into the form of a cup. Or I could fashion a fist-sized ball of thick wet clay then smash that pancake flat. Kneading the material calmed me. I often carved smiley faces into my rough medallions. An outward expression of the peace I gleaned from those drab pieces of clay.

Covered jar, ca, 1675-1700. Tonalá, Mexico. Earthenware, burnished, with white paint and silver leaf, 27 15/16 in. (71 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2015 (2015.45.1a, b)

I have no idea where the clay I kneaded as a child came from, nor the composition that made it suitable material for children’s classes. It only recently occurred to me that much of the clay we use for pottery and ceramic arts comes from the earth. Or that different clays, like kaolin or bentonite, serve different purposes. Across the world, we find rich seams of clay—created from the perfect combination of animal, vegetable, mineral, and circumstance. Kaolin is the result of the decomposition of granite rock over eons, until what remains is a pliable mass of aluminum silicates and other minerals. When we find kaolin deposits, we dig them up and knead them, sometimes throw them on a wheel, then fire what we’ve rendered, making something we call stoneware from a material created out of stone. For eons we’ve done this, we humans, across the world. There are clay deposits in Tonalá, Mexico, from which ceramicists like Fernando Jimón Melchor have formed pieces so prized that for two centuries people coveted them on the other side of the globe, carting the pots across a continent, from the west to the east coast of Mexico, then shipping them across an ocean to be deposited in homes in Italy and Spain. Today, though, many have abandoned connections to this particular part of the earth. Housing developments, built without concern for preserving the clay deposits in Tonalá, threaten the way of life of the potters there.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by Fernando Jimon Melchor (@fernandojimonmelchor)

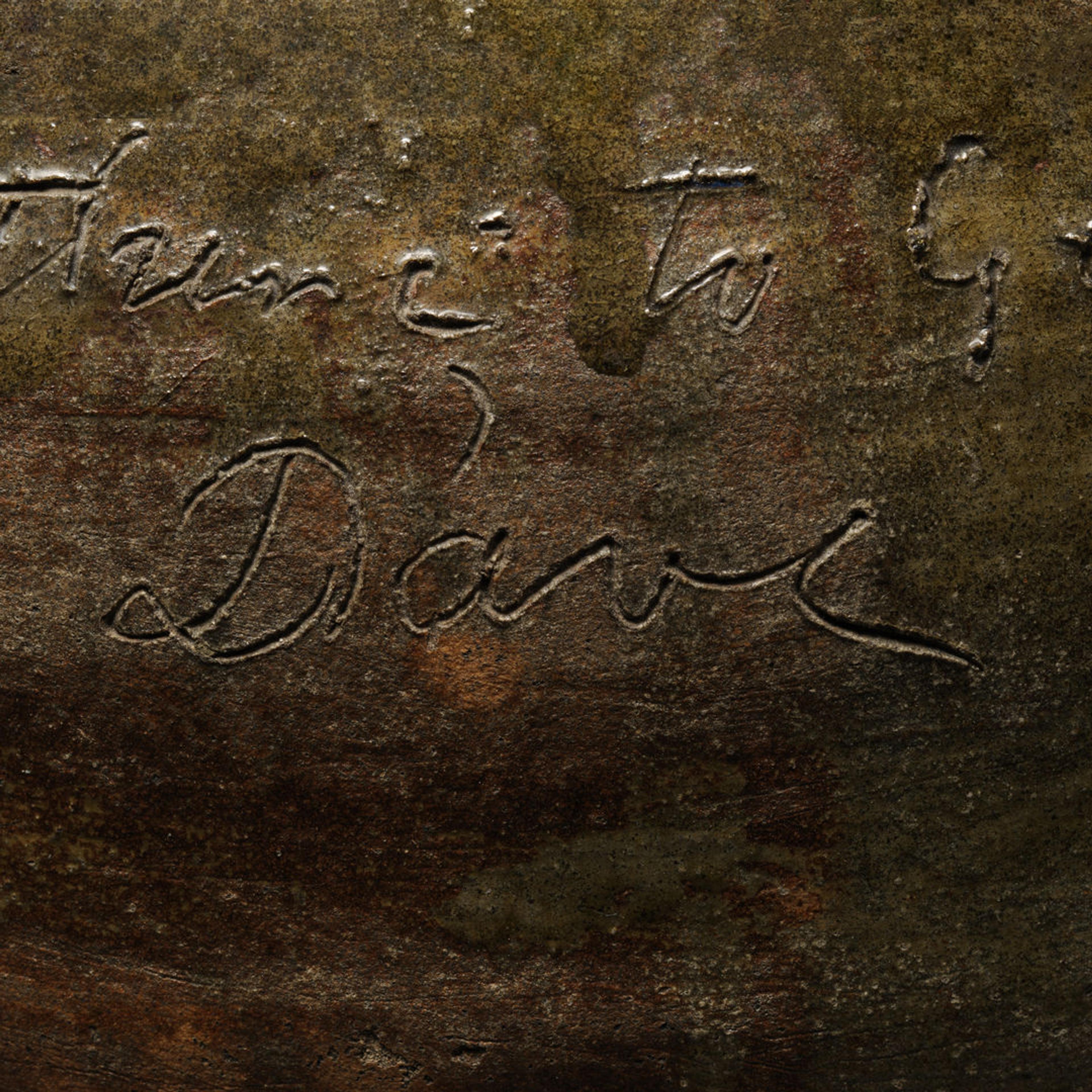

In Edgefield, South Carolina, the clay deposits remain intact. Records dating back nearly five thousand years suggest Native American people made vessels from that clay. Beginning in the nineteenth century, a stoneware industry sprang up in the region, fueled by the labor of enslaved men and women like a man known as Dave the Potter (ca. 1801–70) who inscribed one vessel with these words: “Dave belongs to Mr. Miles / Where the oven bakes and the pot biles.” Edgefield stoneware is known for being water sound and sturdy, fabricated by skillful artisans who worked in often punishing conditions. Dave, one of the most renowned of the Edgefield potters, built massive vessels like one in The Met collection that could hold up to twenty-five gallons. Enormous as they are, and functional, Dave’s pots are also beautiful and often whimsical. On one pot Dave used some of the vessel’s smooth surface to write a witty set of instructions: “when you fill this Jar with pork or beef / Scot will be there; to get a peace.”

Dave (later recorded as David Drake) (American, ca. 1801–1870s). Storage Jar, 1858. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, Height: 22 5/8 in. (57.5 cm); diameter: 27 in. (68.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Ronald S. Kane Bequest, in memory of Berry B. Tracy, 2020 (2020.7)

I am tempted to think of Dave’s inscribed verses as a more accomplished version of the smiley faces I carved into my flat clay medallions in grade school, except that simple comparison erases the bold power and defiance behind Dave’s words. While it was still a colony, South Carolina was the first to pass legislation that banned teaching enslaved people to read and write. In neighboring North Carolina, an enslaved person caught teaching other Black people could be subject to thirty-nine lashes “on his or her bare back.” For a Black enslaved person, to dare to read or write tempted punishment that would leave scars as permanent as words cut into wet clay before a pot is fired. And yet, Dave the Potter wrote on the valued stoneware he created. Even sometimes mocking the people who claimed to own him. “L.M. says this handle will break,” he wrote along the slender handle of one vessel, defying the white man who questioned Dave’s skill. The handle has not yet broken.

Dave lived and worked in the Edgefield area for nearly three quarters of a century. He watched an industry that relied on the materials of the earth and the labor of enslaved people grow up around him. He saw his own family and loved ones sold off and carried away just like the pots he constructed. One of his vessels bears this inscription: “I wonder where is all my relations / Friendship to all and every nation.”

“I am tempted to think of Dave’s inscribed verses as a more accomplished version of the smiley faces I carved into my flat clay medallions in grade school, except that simple comparison erases the bold power and defiance behind Dave’s words.”

Not long after Dave fired that pot in 1857, profiteers evading arrest for illegally trafficking recently kidnapped West Africans smuggled 170 newly enslaved men and women up the Savannah River. The international slave trade had been outlawed for decades. This late ship, The Wanderer, is the second to last known smuggling vessel to dock in the United States. People forced into enslavement by The Wanderer arrived in Edgefield in 1858 and were quickly put to work in the pottery industry, work for which, it turned out, they were well suited. The clay of Edgefield, South Carolina, is very similar to clay found in the part of the Congo the Wanderer survivors once called home. “Concatination,” Dave once wrote on a jar. A word that means a series of interrelated events.

After suffering a journey of indescribable uncertainty and horror. After walking halfway across a continent, from the inland to the coast. After lying shackled in the hull of a ship, slopped in filth and muck and moaning misery. After crossing over five thousand miles of unfamiliar water. After the awfulness of their disembarkation in South Carolina. After dirty hands pried open their mouths to check their tongues and gums and teeth. After forced physical examinations pried into even more. After they chose to swallow strange food or sicken or starve. After learning to recognize the rough sounds of a language suited for a concentrated cruelty. After separation from the place they called home. After separation from families they loved. After the separation from people they knew and animals they recognized. After the separation from a familiar sky. After all that, to find kaolin clay again. To mold it and shape it and fire it just as they had always done. Just as their mothers and fathers. What a confounding mixture of sorrow and joy. Peace, and so much sadness, shaped from the earth.