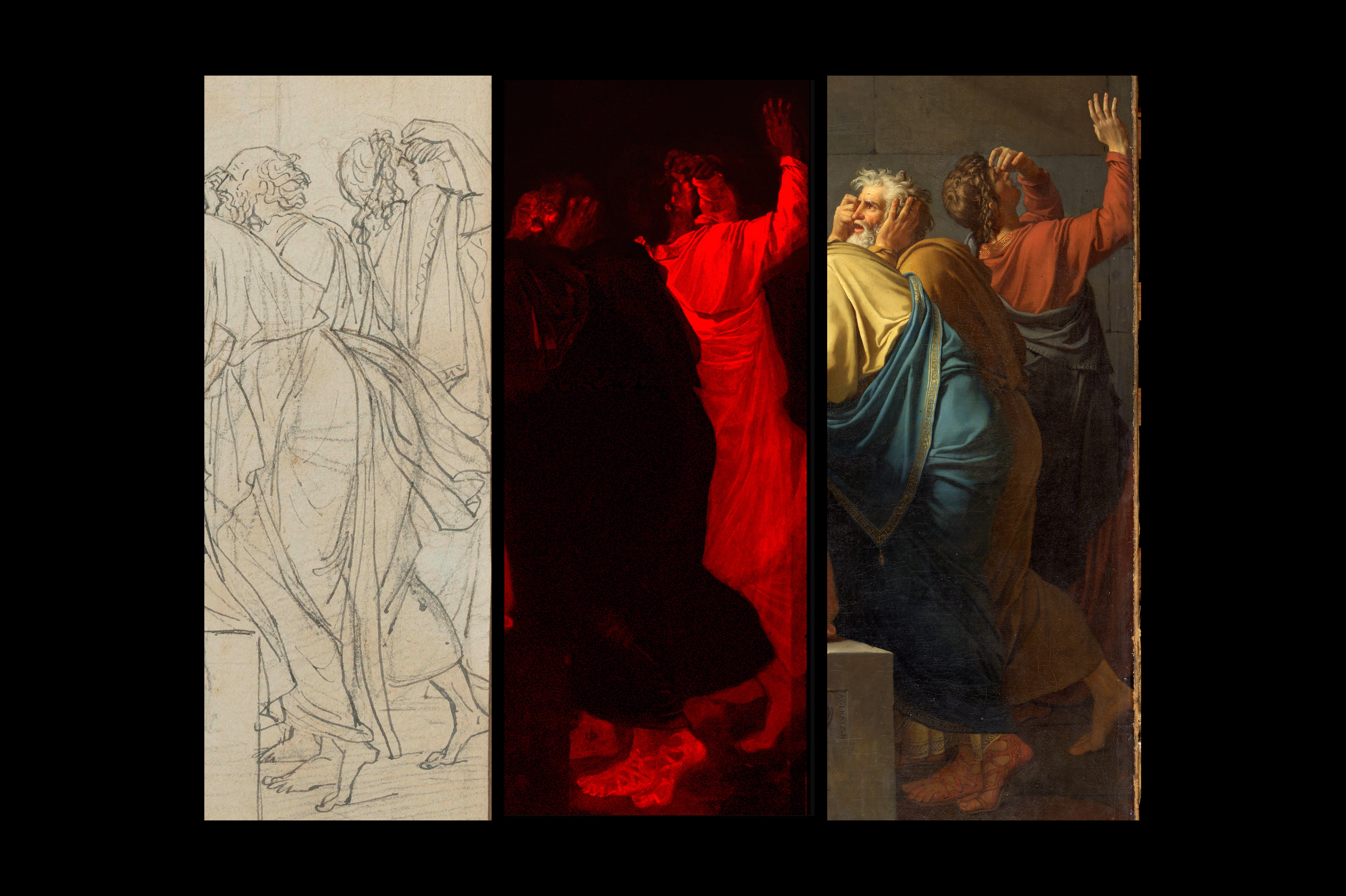

David’s changes and adjustments, for the most part imperceptible from the surface due to his sound and fastidious technique, provide fascinating insight into the artist’s mindset as he painted.

Each detail, angle, and relationship was carefully calibrated, every gesture choreographed.

Through the removal of extraneous features and the refinement of multiple elements, David arrived at a supremely resonant image.

Credits

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). The Death of Socrates, 1787. Oil on canvas, 51 x 77 1/4 in. (129.5 x 196.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1931 (31.45). Photo by Juan Trujillo

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). The Death of Socrates, 1782. Black chalk, brush and gray wash, touches of pen and black and brown ink, with two irregularly shaped fragments of paper affixed to the sheet and a strip added along the upper margin. 9 1/4 x 14 3/4 in. (23.5 x 37.5 cm). Private Collection. Photo by Thomas Hennocque

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). The Death of Socrates, ca. 1786. Pen and black ink, over black chalk, touches of brown ink, squared in black chalk, 11 in. x 16 3/8 in. (27.9 x 41.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter and Leonore Annenberg Acquisitions Endowment Fund and Mr. and Mrs. J. Tomilson Hill and Mr. and Mrs. Mark Fisch Gifts, 2015 (2015.149)

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). The Death of Socrates, ca. 1782–86. Pen and black ink with brush and gray wash over black chalk, with light squaring in black chalk, 9 5/8 x 14 7/8 in. (24.4 x 37.8 cm). The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 2013 (2013.59)

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Seated Old Man (Plato), ca. 1786–87. Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white chalk, squared in black chalk, 19 3/4 x (50 x 59.7 cm). Musée Magnin, Dijon (inv. MMG 1938-234). Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Thierry Le Mage / Art Resource, NY

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Seated Old Man (Plato) with a Young Man Standing Behind Him, ca. 1786–87. Black chalk, stumped, heightened in white chalk, squared in black chalk, 20 13/16 x 14 9/16 in. (52.9 x 37 cm). © Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours, photo by Dominique Couineau

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Study of drapery for the figure of Socrates in 'The Death of Socrates,' 1787. Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white chalk, squared in black chalk, 20 3/8 x 17 in. (51.9 x 43.2 cm). Musée Bonnat, Bayonne, France

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Crito, ca. 1786–87. Black chalk, stumped, heightened with white chalk, squared in black chalk, 21 1/8 x 16 5/16 in. (53.6 x 41.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rodgers Fund, 1861 (61.161.1)

Jacques Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Study for a lamenting figure for 'The Death of Socrates.' 20 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. (52.8 x 35.1 cm). Musée Bonnat, Bayonne, France © Art Resource

Jacques Louis David (French 1748–1825). Study of drapery for two figures at the far right of 'The Death of Socrates.' 21 1/8 x 13 in. (53.7 x 32.9 cm) Musée Bonnat, Bayonne, France

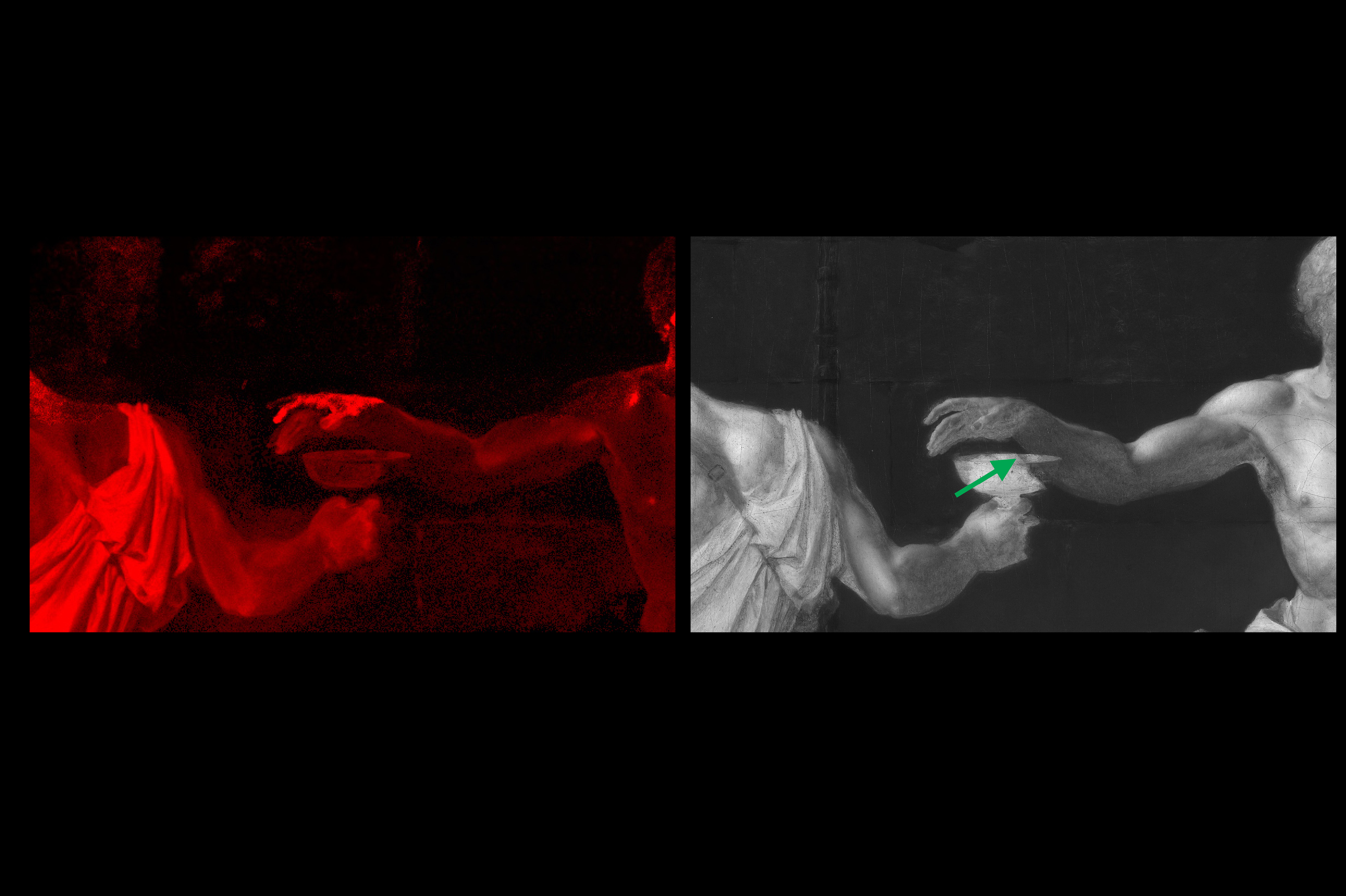

Perspectives diagrams and images acquired by X-radiography and infrared reflectography courtesy the Department of Paintings Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Distribution maps and images acquired by macro-X-ray fluorescence (red for the Hg distribution maps; orange for the Fe distribution map) courtesy the Department of Scientific Research, The Metropolitan Museum of Art