Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts explores the use of French motifs in Disney films and theme parks, featuring forty works of eighteenth-century European design—from tapestries and furniture to Boulle clocks and Sèvres porcelain—alongside 150 Disney objects including film stills, drawings, and other works on paper. The exhibition and its catalogue connect the fantasies of the twentieth-century Hollywood dream-maker with those of the colorful salons of Rococo Paris by highlighting references to European art in Disney films and the artists’ shared dedication to craftsmanship.

My conversation with Wolf Burchard, curator of the show and author of the publication, and Don Hahn, producer of Beauty and the Beast (1991), reveals the fascinating and multifaceted ways in which Disney artists took inspiration from the artists that entertained and delighted the likes of Queen Marie Antoinette of France.

Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

Rachel High: Inspiring Walt Disney focuses on the use of French decorative arts as reference material for Disney’s beloved animated films. Wolf, as curator and author, what made you want to tell this story of Walt Disney and his studio? What is the significance for you to be able to tell this story at The Met?

Wolf Burchard: Organizing The Met’s first ever exhibition devoted to Walt Disney—a giant of American popular art—was both daunting and really exciting. People often describe The Met as an encyclopedic museum, and I felt rather strongly that Disney—a man with such a significant impact on world culture—should be granted entry into that three-dimensional encyclopedia.

Walt Disney is an amorphous figure and does not fit into any of the traditional categories of the visual arts, such as painting, drawing, or sculpture. Even today, many people, especially museum curators, don’t quite know what to make of him. Disney had no pretensions and made no claim to be a so-called “fine artist.” Yet, many of his contemporaries in the 1920s and ’30s—including Frank Lloyd Wright, Erwin Panofsky, and the Lumière brothers—saw him as a pioneer of cinema and a revolutionary artist.

For me, the seamless collaborative effort behind the making of animated cartoons resonated strongly with the large eighteenth-century porcelain, furniture, and tapestry workshops that employed countless artists with different skill sets, all working together to create unified works of art. The parallels we highlight between Disney and Rococo artists in their rhetoric and workshop practices give an additional layer to the exhibition and its catalogue.

High: Don, as producer of Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King (1994), and countless other Disney masterpieces, you were an invaluable resource for Wolf. Is there anything you learned from him while advising for the catalogue? Or something that gained renewed significance?

Auguste Rodin (French, 1840–1917). Detail of The Burghers of Calais, modeled 1884–95, cast 1985. Bronze, overall 82 ½ x 94 x 95 in. (209.6 x 238.8 x 241.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Iris and B Gerald Cantor, 1989 (1989.407)

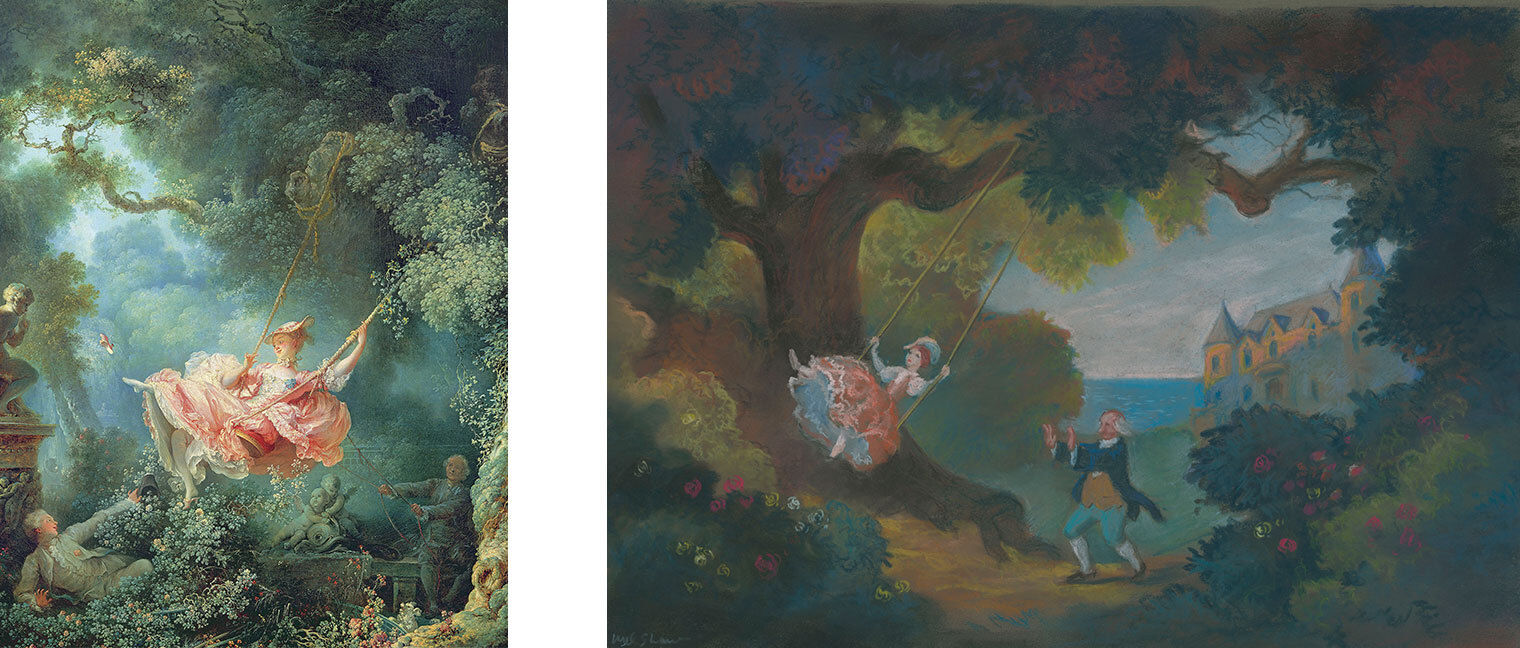

Don Hahn: I was surprised and pleased when Wolf would send me a piece of ceramics, for example, to show how similar it was to an early artwork that one of our artists had done. It just reminds you how deeply immersed the artists were in their work, not just for Beauty and the Beast, but for everything. The team working on Frozen (2013) spent weeks in Norway. For Cars (2006) Pixar artists rented a Winnebago and went on Route 66 for weeks on end. Beauty and the Beast was thirty years ago, and speaking to Wolf reminded me that our inspirations were truly fine art inspirations. Glen Keane, animator of the Beast, looked to Rodin sculptures like The Burghers of Calais (modeled 1884–95)—which we have a copy of here in Pasadena—while working out the anatomy of the Beast transforming. Our painters looked at and referenced works by François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard—especially The Swing (ca. 1767–68)—and picked up on their romanticized style. We are often copyists of the great artists, and they were copyists for the great artists of their time too.

Left: Jean-Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732–1806), The Swing, ca. 1767–68. Oil on canvas 31 7/8 x 25 ¼ in. (81 x 64.2 cm) The Wallace Collection, London (P430). © Wallace Collection, London UK/Bridgeman Image. Right: Mel Shaw (American, 1914–2012), Concept art, Beauty and the Beast (1991). Pastel on board. 16 1/2 x 23 3/8 in. (41.9 x 54.9 cm). Walt Disney Animation Research Library. © Disney

I think that’s what we do as artists. We find the foundation of what we’re talking about and then reinvent it. We weren’t going to make Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (1946). We were going to make our 1990s version in a way we hoped would be relevant. We wanted Belle to be active. We wanted Belle to be bookish. We wanted Belle to want adventure in her life, not just her man. It seemed like so many fairytales were about women whose lives couldn’t start—they couldn’t even wake up—until their man showed up. We were aiming to change that narrative, and these conversations are ongoing. When I worked on Maleficent (2014), we spent so much time with Linda Woolverton—the same writer who was on Beauty and the Beast—talking about how we don’t want to tell our daughters that story anymore. Our job as storytellers and artists is to show people the world through our eyes, and we did that with Belle’s character in Beauty and the Beast.

High: You mentioned a few examples of animators’ fine-art inspirations. The way the catalogue displays European works of art alongside Disney sketches and stills shows how much research goes into every detail of these films. Don, could you speak more about this research process for Beauty and the Beast?

Hahn: Part of storytelling is world-building, and when the lights go down in the theater—or in these days, your living room—you want to transport the audience to a place they’ve never been before. Animation does that especially well, but it is a medium of caricature, so for Beauty and the Beast we didn’t necessarily have to transport the audience to photo-accurate France. In fact, I don’t think we would have wanted to. We wanted to present the audience with an impression of France. It was a really different environment for a bunch of cartoon kids who grew up in Southern California, so we knew that we had to immerse ourselves in the world.

Beauty and the Beast production team members at lunch on the banks of the Loire during their research trip in 1989. Photograph courtesy Hans Bacher

We couldn’t take the whole crew, but eight or so of us spent a few days in the Loire Valley, and we tried to immerse ourselves as much as we could. We knew that going to Paris would be one thing, but going to the countryside would be much more important for this movie. I set up a tour of literally all of the châteaux de la Loire. Some of these châteaux, like Chambord, are vast and empty. Others are intimate and full of everything from period furniture, fabrics, and textiles to leaded-glass windows and antlers on the wall (which inspired Gaston’s tavern scene). We took picture and video references with our funky 1989 cameras.

We had two worlds to represent: Belle’s world, the provincial town, and the Beast’s castle. The Beast’s castle exterior was largely inspired by Chambord, with its huge pile of chimneys, because we needed a fight on the roof at the end, and Chambord offered those different roofscapes. All of the locations in Loire offered some inspiration for the castle interior, but we didn’t see much of Belle’s world in the Loire Valley. I always think it’s amusing when people tell me that they’ve booked a tour that is going to take them to the town that inspired Beauty and the Beast. Where was that? Because I don’t know! There are a million cute towns that it could be, but Belle’s village mostly derived from art and photography books.

Northwestern Façade of Chambord Castle. Photograph by Benh Lieu Song, Wikimedia Commons

High: Wolf, as you alluded, the tradition of referencing European art didn’t start with Beauty and the Beast. The book also talks about the use of European art in earlier animated productions such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Sleeping Beauty (1959). You tell a very wide-ranging story that examines Disney's personal and professional artistic interests as well as those of the larger studio for the last almost one hundred years. I’d like to ask both of you why you think it is important to tell both parts of this story?

Burchard: It is impossible to divorce the man from the company he created. In fact, the company’s ubiquity makes some forget that we are talking about a man who was born 120 years ago—into a world very different from our own. The book is arranged in chronological order. Walt Disney’s personal trajectory sets the scene. We wanted the reader to get an understanding of his aesthetic convictions, his personal taste, and his fascination with European art and storytelling.

Walt Disney in front of an ambulance he decorated with a “doughboy” cartoon (France, early 1919). Photograph courtesy Walt Disney Archives Photo Library

Hahn: Walt was a product of the Midwest. He was a product of European fairytales. His father was a carpenter on the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which was full of stories of travel and adventure. Walt signed up for military auxiliary service underage and the first place he landed was France. Later, in 1935 he went on an extended trip to Europe starting in England. He was really welcomed in London and especially in Paris. Along the way, he bought hundreds of books that he shipped home. Those formed the original studio library at Disney.

Many of those books are still there. It is a really interesting collection to visit because you can see generations of animators and Imagineers have checked them out. The books are all from Disney’s trip in 1935 and feature works by turn-of-the-century artists such as T. S. Sullivant, John Bauer, and Heinrich Kley. Walt brought those books (and some contemporary artists) back from Europe. That was the foundation of Snow White, Pinocchio (1940), Cinderella (1950), and Sleeping Beauty. The early movies that later inspired us were all deeply influenced by those European storybooks. Walt was enamored by them, and you can see that at Disneyland as well.

“Disney animators and the craftspeople of eighteenth-century Paris share the ambition to breathe life into what is essentially inanimate.”

—Wolf Burchard

Burchard: The second half of the catalogue explores the so-called “Disney Renaissance,” the age of a rebirth of hand-drawn animation that took place in the late 1980s and ’90s—long after Walt Disney had died. Beauty and the Beast was one of the trailblazers of that successful era of animation, but it looked back at the visual and narrative traditions set by Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty.

High: It seems fitting that the terminology for that time of immense creativity also references European art. Don, how do feel about this period being called the “Disney Renaissance”?

Hahn: It is important to note that we never used the term “renaissance” during the period—nor did the Renaissance artists in earlier centuries. I don’t think you ever go around saying, “Hey Steve, this is a great renaissance, isn’t it?” You just don’t do that! We hoped we were making good movies, and maybe at our best we were doing work that was on par with what Walt Disney and his people did back in the 1930s and ’40s. Whether we did or not is something for others to answer. I think the idea of an animation renaissance is kind of an oxymoron. Renaissance indicates a certain sophistication where royalty is the client and cartoons are very much for the common man—and proudly so!

Richard Purdum, Tom Sito, Don Hahn, Andreas Deja, Glen Keane, and Jean Gillmore working on an early, abandoned concept for Beauty and the Beast. Photograph courtesy Hans Bacher

High: Changes in technology were a huge part of this renewed energy in the 1990s. In the publication, Wolf speaks about the technical innovations used during the ballroom scene in Beauty and the Beast. Could you speak about how the use of technology evolved at Disney?

Hahn: The nineties were a time of huge technological advance for all of us. Writers started using word processing, musicians started using MIDI, and animators started using digital ink and paint systems that very quickly evolved into a complete digital toolbox, which eventually led to the computer-generated movies that became Pixar’s hallmark.

Except for the very last scene, which was done in the Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) as a test case, The Little Mermaid—released in 1989, just before Beauty and the Beast—was done with pencil, paper, paint, and paintbrushes. Very little change had happened. It was old school, in the same way Snow White was done. Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin (1992), and The Lion King were all done in pencil and paper, but those drawings were then scanned, painted, and compiled in the computer. Before that technology, you could only do three or four layers of artwork. After that technology, you could do three or four hundred; there was no limitation by the physical world. We wanted to use the new technology to create new surprises for the audience. The ballroom was that.

“Cartoons are very much for the common man—and proudly so!”

—Don Hahn

We originally had two surprises, actually, and one failed. We had wanted to create the forest from the wolf-chase scene using the computer. After about six months of working on a tree, the animators were very excited to show us. They said, “Isn’t it great? Look, it moves!” It looked like a chicken claw. We bailed on that pretty quickly.

By contrast, the ballroom was architectural, fitting, and most importantly, it was story driven. In a fairytale the consummation of a love is often dancing. Howard Ashman, Alan Menken, and I talked about the dance sequence in The King and I (1956) as a model for the ballroom scene in Beauty and the Beast. When the characters look into each other’s eyes and Belle grabs the Beast’s hand to begin the dance, it is very romantic. We wanted a visual that went along with that, so that’s where the computer graphics came in.

It was risky only in that we hadn’t done it before, and rendering a single frame of that ballroom sometimes took the whole weekend. You’d come in on Monday and have one frame with one thousand frames left. We thought, “What are we going to do?” We created these render farms of every machine at the animation studio and at Walt Disney Imagineering across the street. We would just render and render and render every waking hour that those computers weren’t being used. We had a fallback which we called the “Ice Capades Fallback.” If the ballroom had not rendered, we would have just placed the animation of Belle and the Beast dancing, which was done by hand, in a pool of light like they were in an ice show. That would have worked, too, but thankfully the ballroom rendered and looked glorious.

The ballroom was a modern miracle at the time—this was four years before Pixar debuted Toy Story (1995). Animation and technology have always been hand in glove. Walt Disney geeked out about technology, so it is a tradition and culture at The Walt Disney Company to play with those things.

Left: James Cox (British, ca. 1723–1800), Automaton in the form of a chariot pushed by a Chinese attendant and set with a clock, 1766. Case: gold with diamonds and paste jewels set in silver, pearls; Dial: white enamel; Movement: partly gilded brass and steel, wheel balance and cock of silver set with paste jewels. Overall: 10 ¼ x 6 3/8 x 3 ¼ in. (26 x 16.2 x 8.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982 (1982.60.137). Right: Automaton Bird in Cage, Manufactured by Bontems, early 1900s. From the Offices of Walt Disney, Burbank, California. © Disney

High: The interest in this technology also reminded me of the French fascination with automatons during the Rococo period.

Hahn: That’s where Walt got it! He picked up a singing automaton bird in a cage—produced by Bontems in Paris—during one of his trips to New Orleans. It is still in his office at the studio, which was restored a few years ago. That bird spawned the idea of the Audio-Animatronics® characters that eventually ended up in the Disney Parks.

He started out by building small characters, things like a vaudeville dancer and the head of Confucius. The 1964–65 New York World’s Fair pushed him into creating the Abraham Lincoln Audio-Animatronics® figure that became a Disneyland attraction in 1965.

High: I feel this all brings us back to the beginning of the interview when Wolf mentioned some of the similarities between the Disney animators and the European artisans. This view of the work is really what sets the publication apart. Could you both speak to your perspectives on that?

Burchard: Disney animators and the craftspeople of eighteenth-century Paris share the ambition to breathe life into what is essentially inanimate. Both their forms of artistic expression seek to evoke motion and emotion. They create fun and witty works designed to prompt emotional responses, not intellectual ones. In fact, Disney famously said, “I make pictures for entertainment, and then the professors tell me what they mean.” It is the kind of sentiment that Rococo artisans are likely to have shared.

Left: Beauty and the Beast (1991), circa 1989. Peter J. Hall (American, 1926–2010), Concept art, Beauty and the Beast (1991). Watercolor, marker and graphite on paper. 23 7/8 × 18 in. (60.6 × 45.7 cm). Walt Disney Animation Research Library. © Disney. Right: Case attributed to André Charles Boulle (French, 1642–1732); After a design by Jean Berain (French, 1640–1711); Clock by Jacques III Thuret (1669–1738) or more likely his father, Isaac II Thuret (1630–1706) Clock with pedestal, ca. 1690. Case and pedestal of oak with marquetry of tortoiseshell, engraved brass, and pewter; gilt bronze; dial of gilt brass with white enameled Arabic numerals; movement of brass and steel. 87 1/4 x 13 3/4 x 11 3/8 in. (221.6 x 34.9 x 28.9 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1958 (58.53a–c)

Hahn: As animators, we’re after the entertainment value, and I’m inclined to agree that we share that with the people who created a piece of porcelain or wove a tapestry in the eighteenth century. We are trying create something that inspires entertainment, wonderment, and awe in our audiences—without showing them the secret. We don’t want to show you the twenty-four drawings per second or the thousands of pencils and gallons of paint that go into a film like Beauty and the Beast. We’d rather have that magic trick be withheld from you. We have that in common with our Rococo counterparts. I think that has been true of the arts forever—whether it’s a craftsperson in the eighteenth century, an Impressionist painter, or an artist of today.

High: One of the strengths of this publication is that it introduces readers to a topic that might not be familiar to them. I think those reading the catalogue for Disney will learn a lot about French decorative arts and those reading for French decorative arts will learn a lot about Disney. Wolf, what do you most want Disney fans to learn about decorative arts and what do you hope decorative-art aficionados take away from the discussion of Disney?

Burchard: Fans of Disney animation or Rococo decorative arts each tend to be extremely enthusiastic about their cherished subject matter. My hope is that we can show both groups that there is as much artistic genius, invention, craftsmanship, and enjoyment in one subject as in the other. If we can get just one or two people to explore that other subject with equal vim, then that would be terrific!

Marquee: Meissen Manufactory (German, 1710–present). Faustina Bordoni and Fox, ca. 1743. Hard-paste porcelain, overall 6 × 11 × 6 ¾ in. (15.2 × 27.9 × 17.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.125)