Inanimate objects dominated the imagery of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris during the collage phase of Cubism from 1912–14. Even so, many of their still lifes possess an undercurrent of human drama thanks to the ingenious combination of things and text. Art historians have argued that the bottles of wine, beer, and spirits, and the glasses, newspapers, playing cards, and smoking accoutrements depicted in so many Cubist still lifes denote male sociability and the masculine realm of the local bar. However, a more nuanced reading of the embedded references reveals that the theme was often the relationship between the sexes.

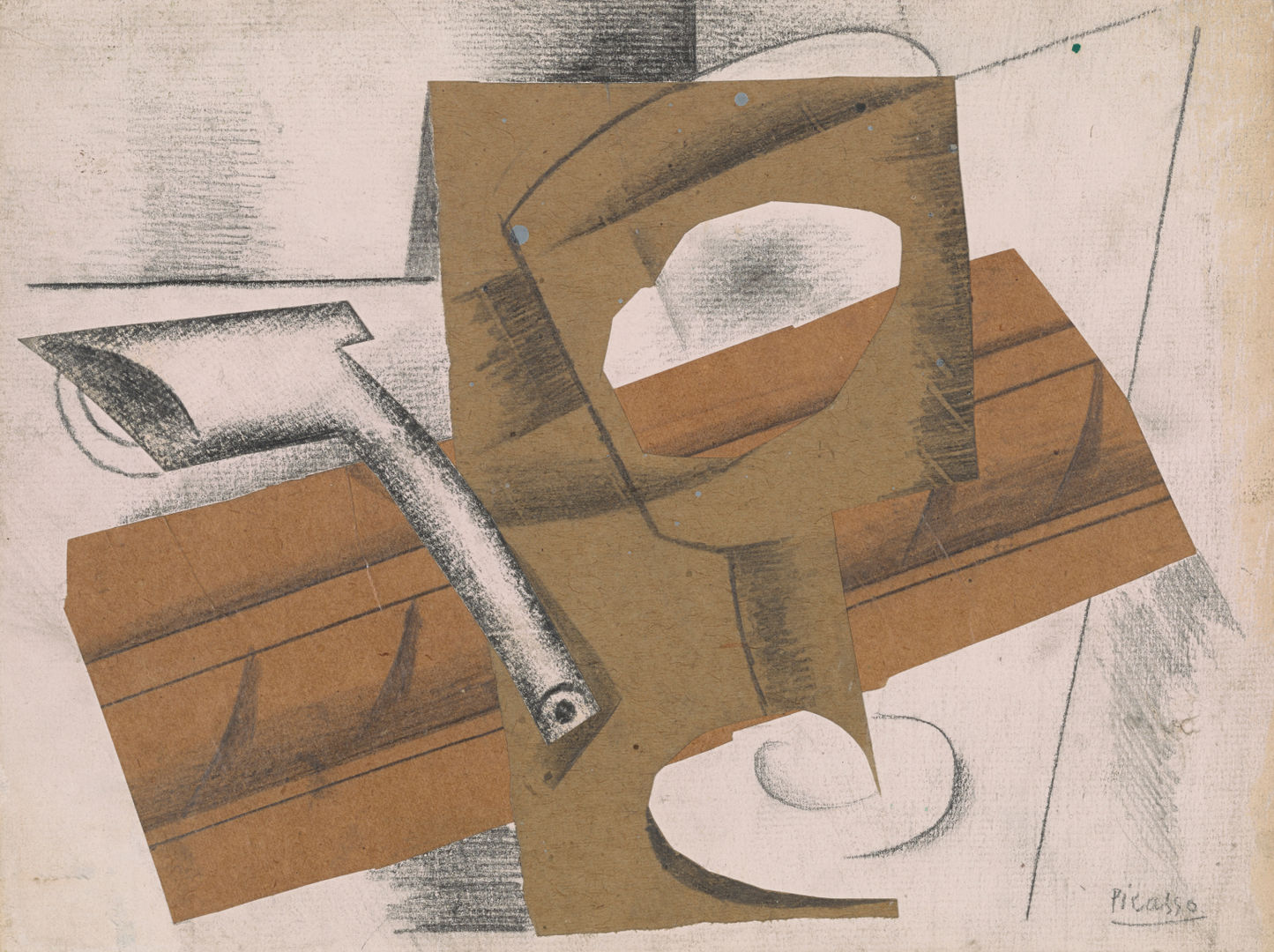

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Pipe and Wineglass, 1914. Cut-and-pasted wove and laid papers and graphite on paper, 7 1/16 × 9 7/16 in. (17.9 × 24 cm), The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Thaw Collection. © The Morgan Library & Museum, New York © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Pipe and Wineglass, 1914. Cut-and-pasted wove and laid papers and graphite on paper, 7 1/16 × 9 7/16 in. (17.9 × 24 cm), The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, Thaw Collection. © The Morgan Library & Museum, New York © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The role of women in society was hotly contested during the early twentieth century. Disputes about women’s nature, rights, and capacities governed the literature on etiquette and filled the pages of the popular press. French feminists challenged the patriarchal doctrine of “separate spheres,” but society still viewed certain objects, settings, and behaviors as intrinsically “masculine” or “feminine.” For instance, pipe-smoking was considered an exclusively male activity: Picasso told the Cubists’ dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, that it would be “monstrous” for a woman to paint a pipe “because she doesn’t smoke it.” Contemporaries would have taken for granted that whenever a pipe featured in a still life, the absent smoker was a man. Picasso, Braque, and Gris—all pipe-smokers themselves—repeatedly used this familiar emblem of masculinity. Picasso kept a stock of cutout pipes ready for instant application: he pasted one into Pipe and Wineglass (1914), indicating that the invisible drinker was a man. Flowers, by contrast, were associated with women. When Gris placed the black silhouette of a clay pipe alongside the bouquet in Flowers (1914), he hinted at an amorous encounter: the objects were surrogates for their owners.

Juan Gris (Spanish, 1887–1927). Flowers, 1914. Conté crayon, gouache, oil, wax crayon, cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, printed wove paper, newspaper, white laid and wove papers on canvas; subsequently mounted on a honeycomb panel, 21 5⁄8 × 18 1⁄8 in. (54.9 × 46 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder, 2021 (2021.395.3) © Metropolitan Museum of Art

Juan Gris (Spanish, 1887–1927). Flowers, 1914. Conté crayon, gouache, oil, wax crayon, cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, printed wove paper, newspaper, white laid and wove papers on canvas; subsequently mounted on a honeycomb panel, 21 5⁄8 × 18 1⁄8 in. (54.9 × 46 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder, 2021 (2021.395.3) © Metropolitan Museum of Art

During his earlier career (1906–12) as a caricaturist for Spanish and French satirical magazines, Juan Gris treated sexual themes in the racy, misogynistic spirit typical of the genre at the time. The accompanying captions spelled out the meaning of the scenes. Gris’s Cubist collages, however, operate through suggestion; he left it to spectators to make sense of the relationship between the objects in a still life. Nevertheless, whenever he incorporated cuttings from contemporary editions of popular French newspapers such as Le Matin and Le Journal, he made sure that the significant text was legible, sometimes using compositional devices to frame and point to it.

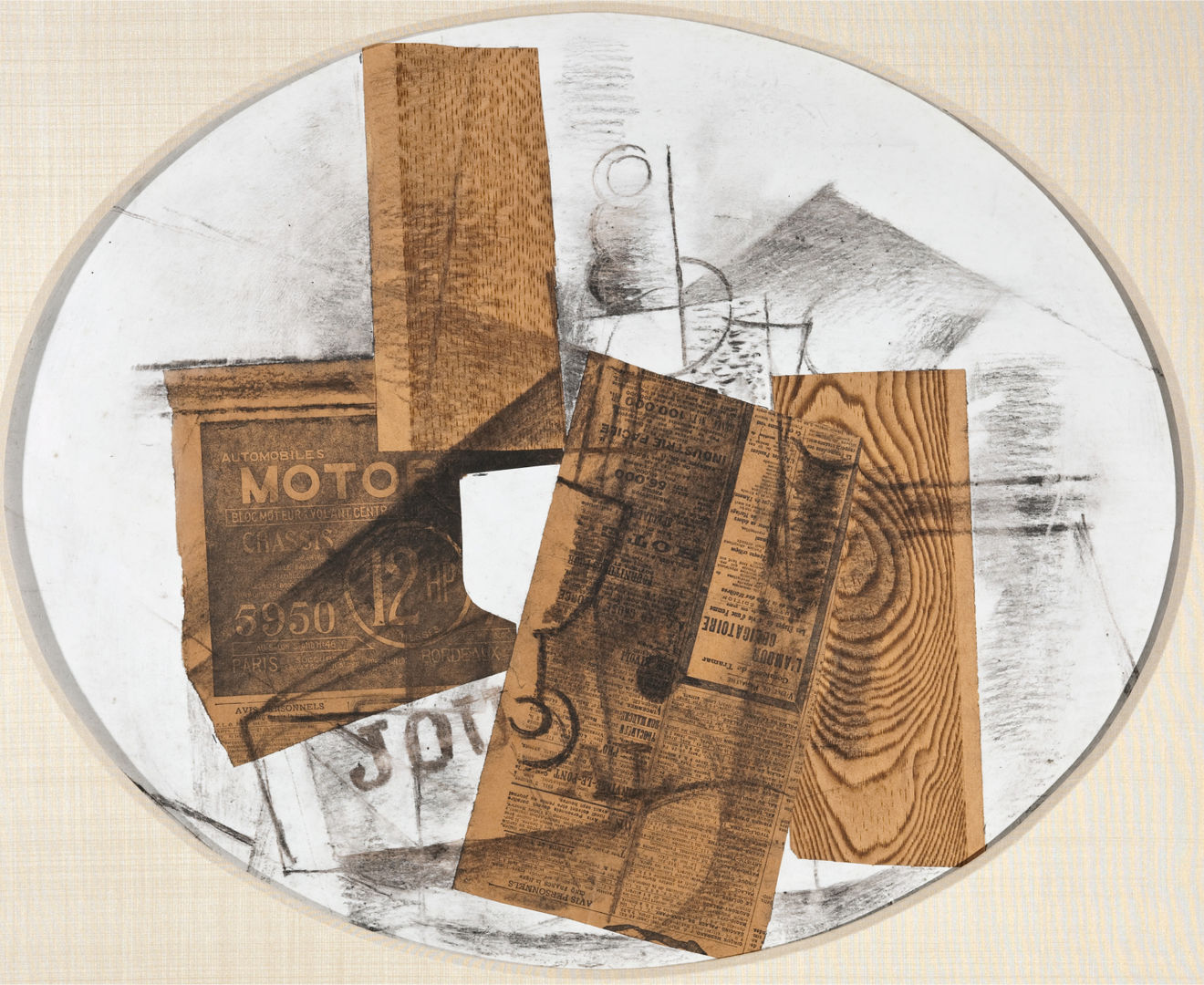

In The Glass of Beer (1914), the word “Femmes” in the newspaper’s headline catches the eye, and one is tempted to interpret the frothing glass as a none too discreet sign of the unseen beer drinker’s lustful fantasies. But the clipping actually came from a leading feminist’s “Appel aux Femmes” (Call to Women) to join the French suffrage movement, following the recent defeat of the bill to give women the vote. Just visible to the right is part of the adjacent article’s headline, “Mme Caillaux, aurait-elle menti?” (Could Mme Caillaux have been lying?). Between March and July of 1914, Henriette Caillaux’s murder of Henri Calmette, editor of Le Figaro and implacable enemy of her husband Joseph Caillaux, the Minister of Finance, was front-page news. Caillaux’s state of mind when she shot Calmette was the burning question: if the murder were judged to be a crime passionnel (crime of passion), perpetrated when she had “lost her mind,” she would get off. Opponents of female suffrage argued that women were subject to ungovernable passion and therefore unfit to engage in politics or to assume any significant role outside the home. In her (ultimately successful) self-defense, Madame Caillaux was at pains to demonstrate her emotional volatility and distance herself from the suffragists. Women were apparently on the mind of Gris’s beer drinker, but his perspective on the contentious “woman question” is provocatively left open.

Juan Gris (Spanish, 1887–1927). The Glass of Beer, 1914. Cut-and-pasted white wove paper, printed wallpapers, newspaper, laid and wove papers, conte crayon, gouache, oil, and wax crayon on canvas, 21 1⁄4 × 28 1⁄2 in. (54 × 72.4 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Bequest of Florene May Schoenborn (1997.544) © The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Georges Braque (French, 1882–1963). Bottle, Glass, and Newspaper, 1914. Charcoal and cut-and-pasted newspaper and printed wallpaper on gessoed paperboard (commercial board from mirror backing), Oval 19 7⁄8 × 24 1⁄4 in. (50.5 × 61.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder, 2016 (2016.237.14) © Metropolitan Museum of Art © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Georges Braque (French, 1882–1963). Bottle, Glass, and Newspaper, 1914. Charcoal and cut-and-pasted newspaper and printed wallpaper on gessoed paperboard (commercial board from mirror backing), Oval 19 7⁄8 × 24 1⁄4 in. (50.5 × 61.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Leonard A. Lauder Cubist Collection, Gift of Leonard A. Lauder, 2016 (2016.237.14) © Metropolitan Museum of Art © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

The sideways text of the glass-shaped cutout (from Le Journal for December 23, 1913) in Pablo Picasso’s Glass and Bottle of Bass (1914) also warrants reading. Picasso found it in the tenth installment of Faubourg Montmartre, Henri Duvernois’s sensational realist novel about the sordid economy of female prostitution in contemporary Paris. The text’s content feminizes the glass. Bass beer was marketed as a man’s drink, and in this collage the bottle appears not just to press up against but to penetrate the glass. Picasso covered the oval cutout representing the table with evenly applied white gouache to give it the look of a linen cloth—or bedsheet. The “picture frame,” crudely assembled from strips of a nineteenth-century trompe l'oeil paper border mimicking the real thing, served to emphasize the tawdriness of the human story embodied in the glass and bottle. His choice of wallpaper as the decorative backdrop was equally studied: a cheap, mass-produced product, it pretended to be an exquisite silk brocade of the Louis XVI period. Ancien régime styles of decoration were favored in Parisian brothels and the wallpaper matched the theme of Faubourg Montmartre.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Glass and Bottle of Bass, 1914. Cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, newspaper, gouache, and charcoal on paperboard, 20 1⁄2 × 26 3⁄8 in. (52 × 67 cm). Private collection © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Lisa Mitchell

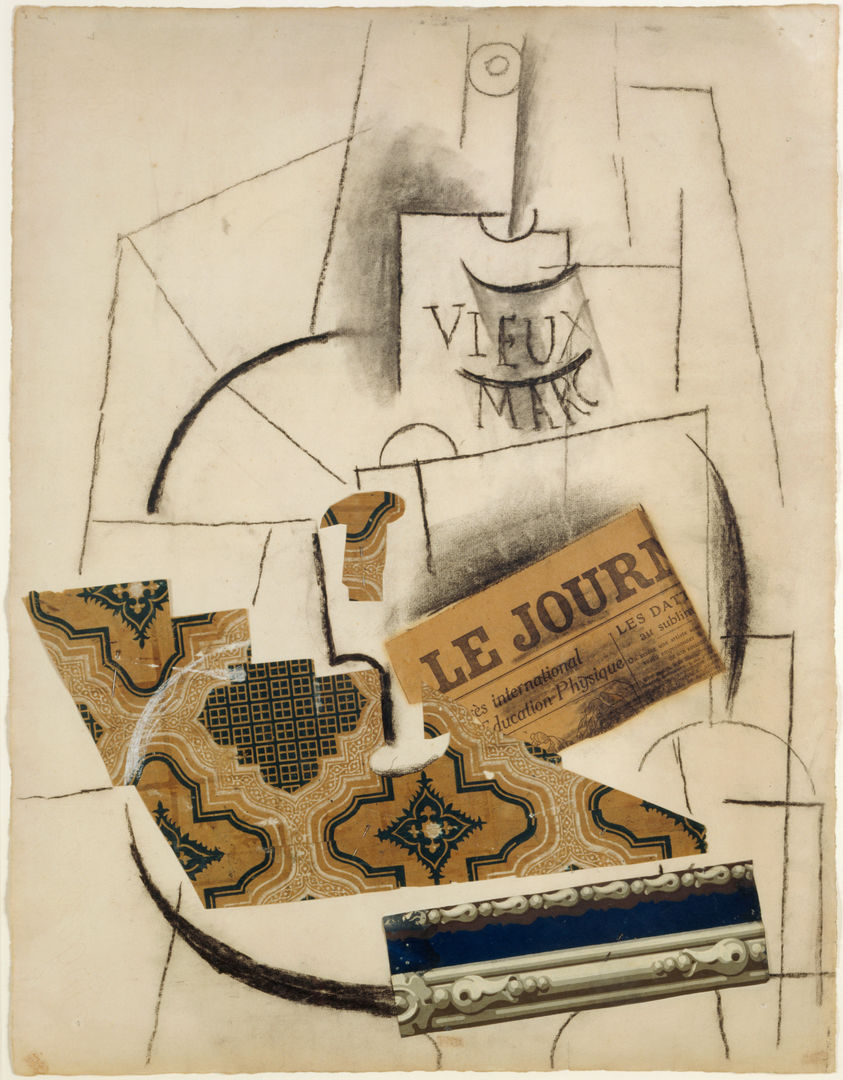

Newspaper aside, wallpaper was the Cubists’ favorite ready-made material. Rather than the expensive block-printed papers for which France was renowned, they used the downmarket, machine-printed variety. The range of patterns and styles was enormous, and many came freighted with gender associations. Contemporary literature on interior decoration defined floral patterns, like the one Picasso chose for Glass and Bottle of Bass, as “feminine” and recommended them for domains conventionally assigned to women: bedrooms, boudoirs, and drawing rooms. The strip of faux-Rococo, rose-and-lace wallpaper that hangs like a curtain in Picasso’s Guitar, Glass, Bottle of Vieux Marc (1913) underscores the femininity of the curvaceous reclining guitar, attended by the (masculine) bottle of brandy. Picasso often resorted to the guitar-as-woman metaphor, which effectively became a Cubist cliché.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Guitar, Glass, Bottle of Vieux Marc, 1913. Chalk, charcoal, cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper, laid and wove papers, and straight pins on blue laid paper, 18 9/16 × 24 5/16 in. (47.2 × 61.8 cm), Musée National Picasso-Paris, Nation Pablo Picasso, 1979 (MP 376) © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Hervé Lewandowski. © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). Guitar, Glass, Bottle of Vieux Marc, 1913. Chalk, charcoal, cut-and-pasted printed wallpaper, laid and wove papers, and straight pins on blue laid paper, 18 9/16 × 24 5/16 in. (47.2 × 61.8 cm), Musée National Picasso-Paris, Nation Pablo Picasso, 1979 (MP 376) © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Hervé Lewandowski. © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

By contrast, mauresque (French for Moorish) designs, like the wallpaper loosely based on Islamic tiles that Picasso used in The Bottle of Vieux Marc (1913) were prescribed for the masculine domains of studies, smoking rooms and clubs. Dating from the 1860s, the mauresque paper was produced at the height of the European fashion for collecting and displaying Islamic artifacts and for orientalist scenes set in mosques by the likes of the French Salon painter Jean-Léon Gerôme. With typical wry humor, Picasso teamed the paper with a bottle of French brandy and a newspaper reporting a crime-of-passion story involving poisoned dates.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881–1973). The Bottle of Vieux Marc, 1913. Cut-and-pasted printed wallpapers, newspaper, charcoal, gouache, and pins on laid paper, 24 13/16 × 19 5/16 in. (63 × 49 cm). Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Donation of M. Henri Laugier, 1963 © CNAC/MNAM/Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Philippe Migeat. © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York), New York

The Cubists’ use of wallpaper and recourse to collage transgressed accepted gender norms in an important way. Before World War I, the design, manufacture, marketing, and hanging of wallpaper were almost entirely in the hands of men, but choosing wallpaper was mainly a woman’s business. Advice on interior decoration in manuals and magazines was usually addressed to women and humorous postcards depicted them hesitating between the innumerable options, attended by unctuous salesmen and hovering husbands. Arguably, the Cubists were encroaching on women’s territory when they chose wallpapers for their collages, pastiched wallpaper patterns in their paintings, and gave their still lifes decorative settings. Historically, moreover, the popular amateur craft of collage had been practiced principally by women. It was mainly women, for instance, who pasted keepsakes into family albums or prints and scraps onto screens and lampshades, and who assembled ornaments from miscellaneous bits and pieces. When Picasso attached his cutouts with dressmaking pins and left those pins in the finished work, as he did in Guitar, Glass, Bottle of Vieux Marc and The Bottle of Vieux Marc, he drew attention to the femininity of the collage process.

"On songe au nid" (Dreaming of the Nest). Humorous French postcard, postmarked 1903, depicting a woman, accompanied by her husband, choosing wallpaper with the aid of a salesman.

Cubist collage was unashamedly streetwise in its overt references to contemporary news and products. The ready-made materials the artists appropriated could be bought from kiosks and general stores, and the cut-and-paste (and pin) technique seemed to require no special skill. The themes, whether momentous or scandalous, that they surreptitiously addressed in their still lifes were of the immediate moment. Not least among them was the urgent and divisive “woman question” that—albeit posed in different terms—has never gone away.