This excerpt is from Elizabeth L. Block’s Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion, a book that shows how wealthy American women—as consumers and as influencers—helped shape French couture of the late nineteenth century. Elizabeth L. Block is a senior editor in The Met’s Publications and Editorial Department.

Dressing Up is available October 2021 from MIT Press.

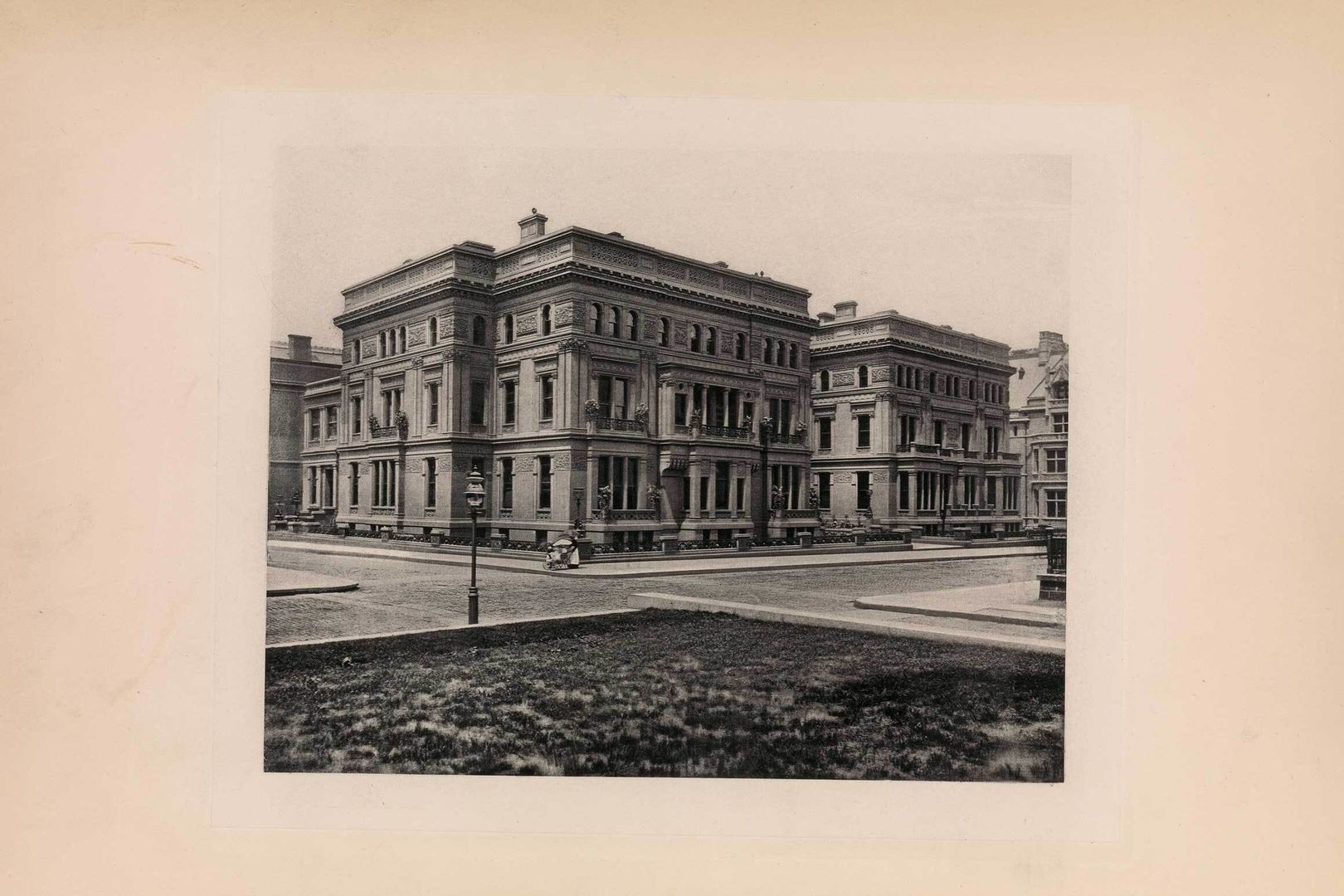

William Kissam Vanderbilt and Alva Vanderbilt moved into their new mansion at 660 5th Avenue at 52nd Street in 1883. The house, which cost a reported $3 million to build, was well known to be their effort to establish themselves in high society, having formerly been derided as nouveau riche.

Alva Smith’s family was from Mobile, Alabama—“plain Miss Smith, mind you,” wrote one reporter [1]—but both her parents’ families held money and stature in local and national government. At their cotton plantations, they enslaved laborers, and in her memoir, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont recalled that her mother had “inherited” workers. She remembered a servant named Monroe who had previously been enslaved by her mother and with whom Alva would go to the market after the family moved from Mobile to New York. She wrote of her mother’s avid preference of French dress for herself and her daughters, especially from Madame Olympe of New Orleans. Alva recalled that as a child she resented having been made “a pioneer in the matter of clothes,” as well as the attention she received for her “extraordinary amount of hair.” As an adult, however, especially during the years of her two marriages, her interest in a rich appearance was undeniable.

Despite Alva’s childhood summers in Newport, France, Austria, Italy, Belgium, and Germany, her family’s fortunes changed when she was a teenager and when her father’s businesses declined in about 1875. From then onward, both she and William Kissam Vanderbilt sought approval from the old-money Knickerbocker families like the Astors and Schermerhorns, and courted newspaper editors to help the cause. The four-story limestone house was conceived as a French Renaissance “petit château” in the style of François I, a deliberate choice that associated it with French royalty and that would be copied by a number of elite homes in New York, including the Henry G. Marquand House on Madison Avenue at 68th Street.

Alva Vanderbilt had lived and studied in Paris with her mother and siblings between 1866 and 1870 and recalled fondly her formal education there, including etiquette lessons on how to conduct oneself at an evening entertainment. After returning to New York, she remembered that her mother shipped their French furniture to their rented home at 14 East 33rd Street and that going to such an extreme was an unusual decision at the time. Vanderbilt retained a taste for all things historically French and presumably followed the progressions of French interior design, which were amply circulating throughout the world in collecting and decorating manuals.

Edward Strahan (Earl Shinn) (American, 1838–1886), Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection (Boston: George Barrie, 1883–84). 4 volumes, illustrations, 19 in. (48 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (106.1 V28 F)

Vanderbilt worked closely with architect Richard Morris Hunt on the design of the house at 660 5th Avenue and later referred to him as one of her closest friends. She instructed him on her preference for what she called medieval style but that was truly a combination of French Gothic and Renaissance. Herter Brothers designed the banqueting hall, and Jules Allard’s well-known French firm was contracted for the eighteenth-century Régence salon. The entrance hall was executed in Caen limestone, and the dining hall had ceilings of oak and windows created with pieces of medieval stained glass. Other rooms were appointed with Aubusson carpets and Gobelin tapestries, the latter evoking the grandness of the court of Louis XIV, as the Gobelins manufactory had become the Royal Manufactory of the Crown’s Furnishings in 1664.

Shortly after the house was finished in 1883, William Kissam Vanderbilt published several catalogs of his art collection and engaged Edward Strahan (pseudonym for artist and critic Earl Shinn) to write the text of a four-volume handbook, Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection, with lavish illustrations of the decorative highlights. The Vanderbilts became known for using this type of self-promotion to amplify their taste as publicly as possible, an effort that for the most part was successful, although the level of societal acceptance remained varied. In her memoir, written in 1917, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont remained proud of the house, which by then had been destroyed.

On Monday, March 26, 1883, the Vanderbilts held a fancy dress ball with hundreds of guests, spending a rumored $250,000 in total. Without a specific theme from the hostess, people arrived in costume from multiple eras. Vanderbilt dressed as a Venetian princess, based on a painting by Alexandre Cabanel, and her husband was the “Duc de Guise,” possibly after a painting in his art collection. [2] As did most balls, this one began late at night. Advancing past the police-patrolled spectator crowds, they arrived at about 11:00 p.m., the eight-course dinner was served at 2:00 a.m., and they departed at daybreak. The timing indicates that the majority of partakers was not required to report to jobs in the morning.

Attending the opera was an act that had become coded for the leisure classes, warranting entire chapters in etiquette books on the specifics of appropriate dress. The multifarious influences of the opera on the ball that followed are worthy of consideration. On March 26, Rigoletto played at the Academy of Music on East 14th Street and Irving Place, the most highly respected venue at the time. [3] The first scene is a ball held at the palace of the sordid Duke of Mantua. The duke takes a liking to Gilda, the daughter of his jester, Rigoletto. Gilda has only seen the duke in his disguise as a student and wishes to be with him, but her father explains the man’s true identity and attempts to dissuade her. He has her dress as a man so that she may escape safely to Verona; however, she manages to return and, still dressed in men’s clothes, is killed in a case of mistaken identity.

House of Worth. “Electric Light” ensemble. Silk satin and velvet with silver and gold metallic tinsel and silver paillettes. Museum of the City of New York, Gift of Countess László Széchenyi (51.284.3A-H).

Guests at the Vanderbilt ball would have watched and listened to these scenes of artifice leading to tragedy before donning costumes themselves and enacting their own show at the party. The themes ranged from allegorical and historical to technological, with Alice Claypoole Gwynne Vanderbilt famously wearing a House of Worth dress representing electric light. Outfitted with a battery-powered torch, it was the height of contemporaneity, as Thomas Edison’s lightbulb invention was then available in only a few private homes. During the ball, “the house was in a blaze of light, which shown upon profuse decorations of flowers” by the society florist Charles F. Klunder, who created the ambience of a “garden in a tropical forest.” Cora Brown-Potter came as the eponymous opera character Madame Favart, holding a mandolin. [4] Worth created a phoenix-themed gown for Emily Taylor Lorillard, the long train of which was decorated with a crimson cashmere border embroidered with “leaping flames.” Caroline Astor wore a dark, Venetian-inspired dress of velvet and satin, with a diamond aigrette in her loose, long hair.

Hornet costume in Ardern Holt, Fancy Dresses Described: Or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls (1879).

The costume selections derived from such handbooks as Ardern Holt’s Fancy Dresses Described: Or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls, first published in 1879. The guide provides a fascinating glimpse into the zeitgeist of the late 1870s and the 1880s. Listed alphabetically, the themes of electric light, newspapers, photography, postage, and telegrams were included with those of allegorical, historical, and Shakespearean figures, and among the most intriguing were doll pin cushion, chocolate cream, and hornet. The latter two were taken up, with some interpretation, at the Vanderbilt ball by Jennie (Jenny) Bigelow, who came as La Belle Chocolatier, and Constance Rives Borland, who came as a hornet in yellow satin and a brown velvet skirt. Borland was not the only hornet that night: Eliza (Lila) Osgood Vanderbilt Webb wore nearly the same costume, a testament to how closely readers adhered to Holt’s suggestions.

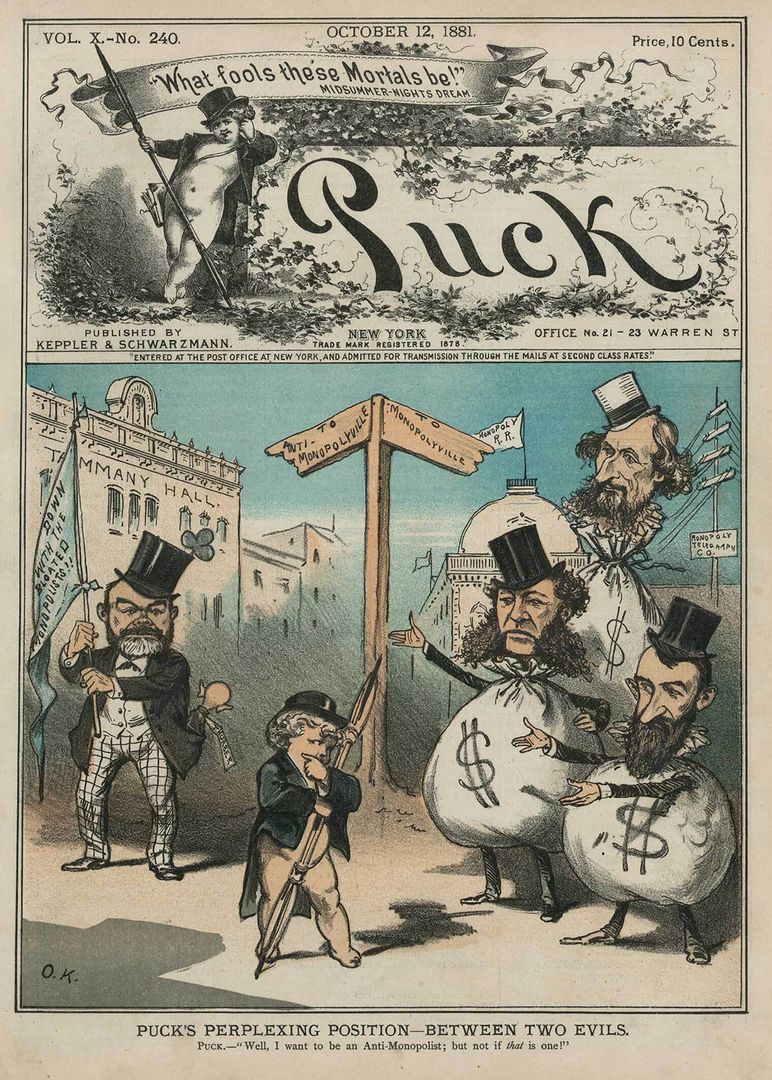

Cornelius Vanderbilt II, Alva’s brother-in-law, dressed as Louis XVI, a Bourbon monarch destined for the guillotine, as did seventeen other men, according to the New York Times. In Alva’s memoir, though, there is no acknowledgment of the ironic association with a counterrevolutionary deposed king. And this was at a time when the Vanderbilts and other prominent families were continuously criticized for monopolizing entire industries and lampooned for their opulent lifestyles, as were William Henry Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, and Cyrus W. Field in the humor magazine Puck. William Henry Vanderbilt was alternately called a “merciless millionaire” and the “modern colossus of (rail) roads” in its pages. Rather, in Alva’s memoir, she wrote about fashion: “Many of the costumes, including Lady Mandeville’s and mine, came from Paris.” She recalled that Consuelo Yznaga came as Queen Maria Theresa of Austria and that her own dress was of white satin with elaborate gold embroidery, a velvet mantle, diamond diadem, and additional diamond and emerald jewelry completed the outfit.

Puck, October 12, 1881, cover. Image courtesy the Library of Congress

This loose, vaguely escapist historicism also manifested in dressing as the subjects of painters like Titian, Velàzquez, Watteau, Reynolds, and Gainsborough. Servants, however, were required to dress as wait staff of a historical period.

Guests at the Vanderbilt ball were dressed in the finest that was to offer, and after attending the opera, they would have first returned home for their own costume change or, attended by servants, used one of the dressing rooms made available by the hostess of the ball. They would not have attended the opera in costume. The evening’s proceedings, especially this interlude between the two main events, suggest a poignant blending of the experience of watching the opera and then embodying a different character at the ball, realized through a change of clothing, hairstyle, and makeup. In terms of the setting, the scene changed from the established opera house to that of the new mansion of an arriviste family.

The theatrics of debuting fancy dress ball costumes were not lost on the press, which was an integral part of the institution of fashion. Godey’s Lady’s Book covered the Vanderbilt ball thoroughly, and photographs of guests in costume taken by Jose Maria Mora were distributed widely via cabinet cards. [5] Mora’s black-and-white photographs provide an invaluable record of the costumes worn by prominent attendees. [6]

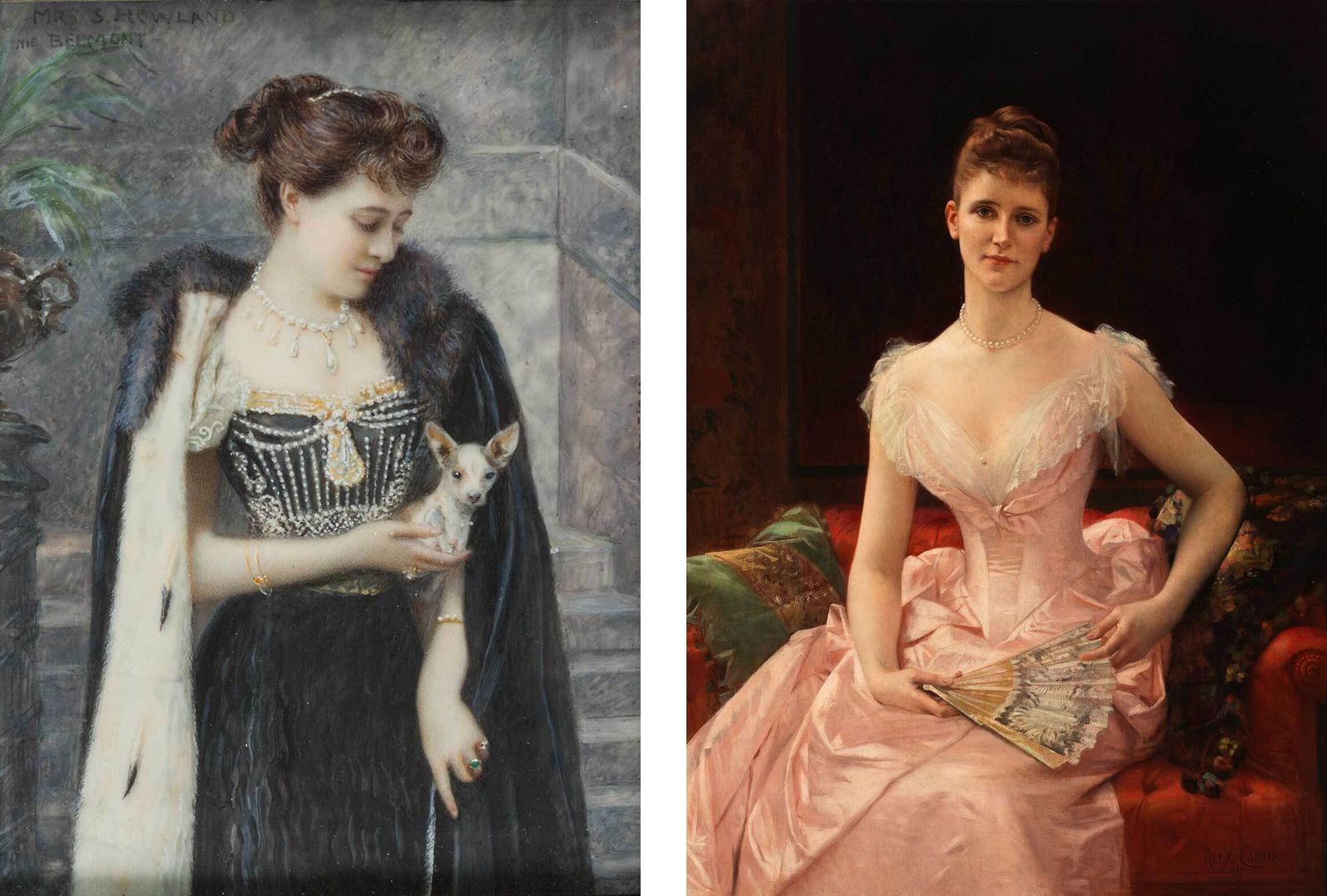

Left: Carl A. Weidner (American, 1865–1906) and Fredrika Weidner (American, 1865–1939). Mrs. Samuel Shaw Howland (Frederika Belmont) (detail), 1898. Watercolor on ivory; silver gilt, 9.8 × 7.6 cm. New-York Historical Society, Gift of the Estate of Peter Marié (1905.112). Photograph © New-York Historical Society. Right: Alexandre Cabanel (French, 1823–1889). Olivia Peyton Murray Cutting, 1887. Oil on canvas, 132 × 99 cm. Museum of the City of New York, Gift of the daughters and granddaughter of Mrs. William Bayard Cutting through Mrs. Bayard James, 1950 (50.60.1).

Formal portraits and miniatures are helpful when viewed alongside photographs from balls as testimony that couturiers furnished a range of garments from daily wear to fancy dress ball costumes and that the latter were not considered a lesser endeavor (as they were regarded later in the twentieth century). There was no strict division between costume and fashion as there is today. Although we do not know the names of the makers of Frederika Belmont Howland’s costume for the Vanderbilt ball or the jeweled ensemble with ermine-lined cape she wore for her portrait miniature in 1898, the fastidious detail of both attests to Howland’s exacting eye. A photograph by Mora of another guest, Olivia Peyton Murray Cutting, shows that her eighteenth-century costume for the ball was completed by a powdered updo and floral hair piece. Dressing in character may have emboldened the sitter to adopt a direct gaze at the camera. Four years later, for her portrait by Alexandre Cabanel, her attitude is more traditional, her pale pink satin and lace ballgown was formally arranged with complementary fan, and her chestnut-colored hair is set in a conservative high chignon.

Benjamin Curtis Porter (American, 1843/5–1908). Emily Thorn Vanderbilt Sloane, 1888. Oil on canvas, 257.3 × 126.4 cm. Vanderbilt University Portrait Collection, Nashville, Tennessee.

Finally, Emily Thorn Vanderbilt Sloane, a daughter of William Henry Vanderbilt, who would live with her husband in part of the “Triple Palace” on 5th Avenue, opted for a Little Bo Peep costume made by Catharine Donovan. [7] Donovan may have consulted a guidebook like Holt’s, which includes a Bo Peep listing. Five years later when Sloane sat for her portrait by Benjamin Curtis Porter, she chose a formal white ball gown with yellow taffeta trim.

Once inside the mansion, the guests-turned-characters flooded the elaborate rooms of 660 5th Avenue. A set of young guests performed six quadrilles (dances with four couples) that they had practiced for weeks; two multipiece bands provided the music. In the case of the Dresden Quadrille, the women dressed and powdered their faces in white to resemble Dresden china, becoming living statues within a home that abounded with sculpture, painting, and decorative arts. Other quadrilles, including one with life-size hobby-horses attached to the waists of the dancers, flowed from the third-floor supper room (called the “gymnasium”), down the grand staircase, and into the drawing room on the second floor. The choreographed dances crossed through several sections of the house, inserting bodies, fabric, and props into spaces that had not yet been fully inhabited, the house having been finished only days before. Hundreds of other unchoreographed guests also enlivened the rooms, their costumes often voluminous with formidable headdresses. Kate Fearing Strong famously wore a stuffed white cat to top off her feline outfit, the skirt of which was composed of sewn white cat’s tails. [8] Her nickname, “Puss,” is inscribed on a blue ribbon around her neck, from which hangs a bell.

Jose Maria Mora. Kate Fearing Strong at the Vanderbilt Ball, 1883. Museum of the City of New York (F2012.58.1460).

The notion of the guests wearing their outfits and setting them into motion within the freshly built Vanderbilt house is a poignant demonstration of how fashion interacts with interior spaces. As John Potvin and Louise Crewe emphasize, fashion and spaces work upon one another, leaving lasting impacts. [9] It is fitting to invoke here what theorists Joanne Entwistle and Elizabeth Wilson have so astutely termed the “embodied practices” of fashion. Although the skeleton of the Vanderbilt house was filled with a sizable collection of furniture, paintings, sculpture, textiles, and decorative objects by the most desired artists and designers of the period, the space did not function as a home and showpiece for the owners until it was activated by the bodies, heat, and fabrics of the guests who actually warmed the house.

The satirical “Town Terrier” columnist in Puck magazine joked that “the most richly dressed person in the ball-room” had “two certified checks for $250,000 each” enwreathed in her hair. A reporter in Maine condemned the elaborate affair. Tellingly, he used language describing materials but not distinguishing between interior decoration and people to conjure the overall atmosphere: “And so throughout the whole affair—there was the artistic manipulation of velvet, satin, ermine, silk, diamond, pearls, silver and gold.” [10]

Notes

[1] “Her Millions for a Coronet,” The Redwood Gazette, November 7, 1895, 7; Sylvia D. Hoffert, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont: Unlikely Champion of Women’s Rights (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 1. Return

[2] See, for example, “Festivity at Eastertide,” New York Times, March 25, 1883, 14. Charles H. Crandall, The Season: An Annual Record of Society in New York, Brooklyn, and Vicinity (New York: White, Stokes, & Allen, 1883), 298–299; Ward McAllister, Society as I Have Found It (New York: Cassell, 1890), 354; Eric Homberger, Mrs. Astor’s New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 14; Wayne Craven, Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society (New York: W. W. Norton, 2009), 125–126; Susan Gail Johnson, “Like a Glimpse of Gay Old Versailles: Three Gilded Age Balls,” in Gilded New York: Design, Fashion, and Society, ed. Donald Albrecht and Jeannine Falino (New York: Monacelli Press, 2013), 89. Return

[3] “Amusements This Evening,” New York Times, March 26, 1883; “Mme Patti in Rigoletto,” New York Times, March 27, 1883, 5. Return

[4] Crandall, The Season, 296; “The Vanderbilt Ball,” New York Tribune, March 27, 1883, 5; “New York’s Great Dazzle,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 29, 1883, 2. Return

[5] For example, “New York City Life,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 15, 1883; Albrecht and Falino, Gilded New York, 45. Return

[6] Mora’s photographs of the Vanderbilt ball are held in the Museum of the City of New York, the New-York Historical Society, and the Preservation Society of Newport County. Return

[7] I am grateful to Kevin Jones and Christina Johnson for sharing their knowledge and images of this ensemble. Return

[8] “New York’s Great Dazzle,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 29, 1883, 2. Return

[9] John Potvin, ed, The Places and Spaces of Fashion, 1800–2007 (New York: Routledge, 2009); Louise Crewe, The Geographies of Fashion: Consumption, Space, and Value (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017); Heidi Brevik-Zender, Fashioning Spaces: Mode and Modernity in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015). Return

[10] “Wicked Extravagance,” Maine Farmer, April 5, 1883, 2. Return

Citations from this excerpt have been reduced and, where appropriate, replaced with links to research volumes. For a complete list of sources, see: Elizabeth L. Block, Dressing Up: The Women Who Influenced French Fashion (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021).