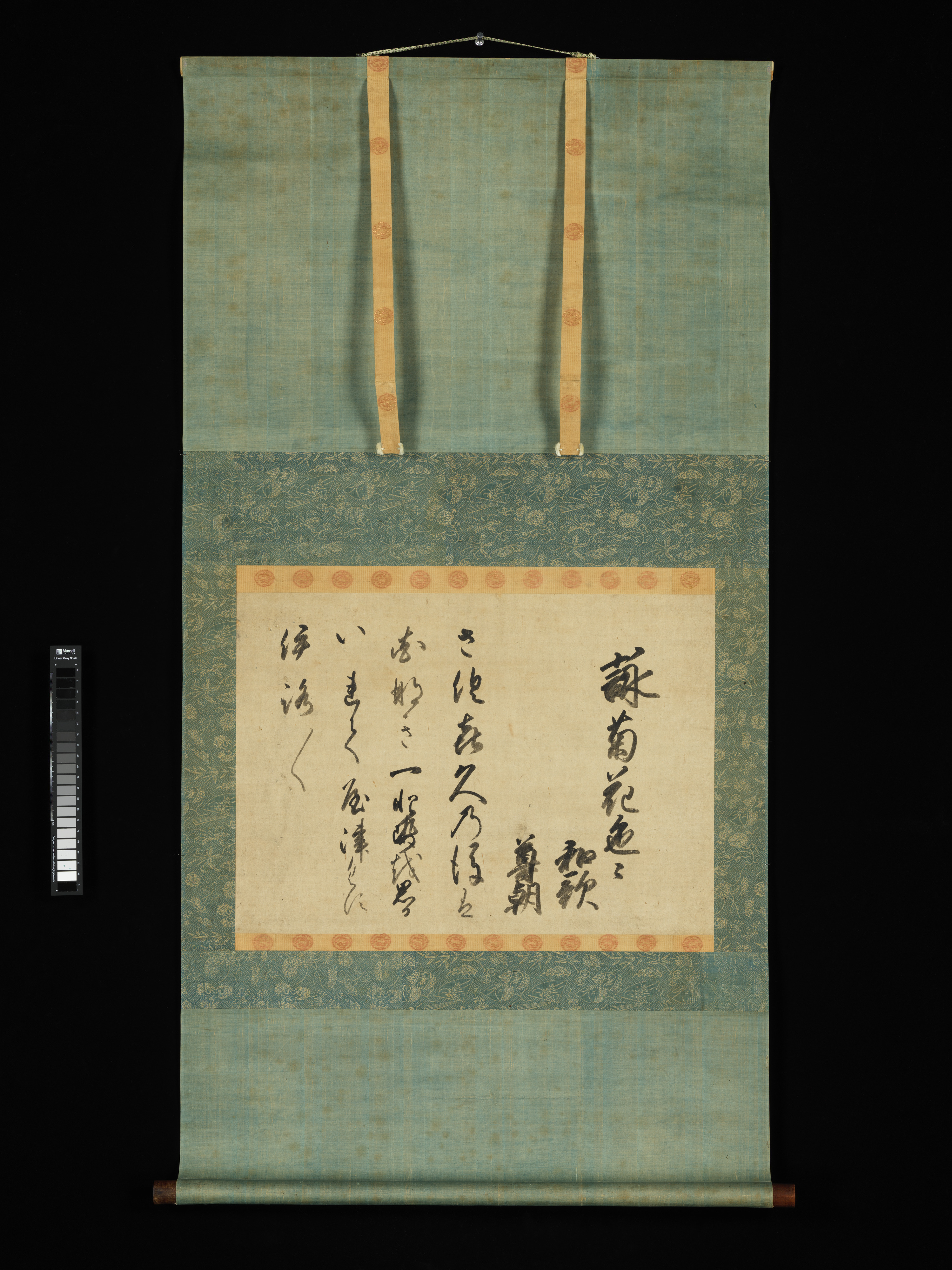

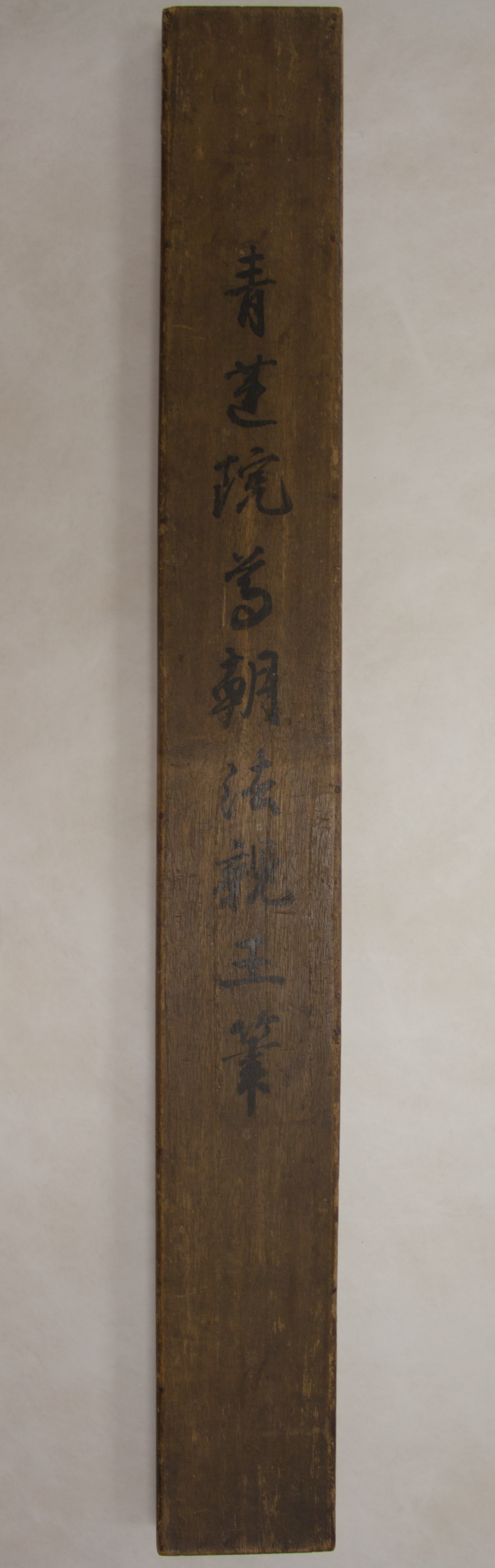

Waka Poem on Chrysanthemums

Shōren’in Sonchō Hosshinnō 青蓮院尊朝法親王 Japanese

Not on view

.

This solitary inscribed poem, adhering to the conventional structure of a waka kaishi, or poetry sheet inscribed by the author of the poem, encapsulates the history and role of the Shōren’in lineage of court calligraphers. through late medieval times, the Shōren’in temple was the primary center for orthodox training in court styles of calligraphy. The most famous calligraphers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, including Prince Sonchō himself, all began their studies here.

In this work, Sonchō demonstrates his mastery of archaic kana calligraphy by employing sōgana, highly cursive Chinese characters (kanji) used phonetically in place of conventional kana syllables (which are even more abbreviated and minimalist in appearance), so the visual weight of kana can hardly be distinguished from the kanji. As can be seen in the transcription, there are only three kanji used in the transcription of the poem proper, but almost all of the thickly brushed kana are as dense or denser in appearance than the kanji. This is an intentional technique, one that the celebrated Hon’ami Kōetsu would also use in his calligraphic compositions, though it is a more radical manner. With the exception of two places in the second and third columns of the poem, each graph stands on its own, whether kana or kanji, giving the composition a slow, grand pace. The poem can be deciphered and translated as follows:

詠菊花色々 和歌 尊朝

Ei kikuka iroiro / waka / Sonchō

A waka recited by Sonchō on the topic of the various colors of chrysanthemums

さくきくの 後は花なき 一とせを

思るいまてや つくすいろ/\

Saku kiku no

nochi wa hana naki

hitotose o

omouru imade ya

tsukusu iroiro

After the chrysanthemums

bloomed and lose their flowers,

I sentimentally reflect on

the passing of the year till now

in all its various tinges.

We have no surviving evidence documenting the circumstances or poetry gathering for which this waka kaishi was composed, but we have to keep in mind that anytime a member of royalty talks about chrysanthemums we inevitably associate it with an allusion to the royal family, whose official crest to this day is that flower. Sonchō was born into the royal family as son of Prince Fushimi no Miya Kunisuke, and then was adopted at age six by Emperor Ōgimachi, a highly cultured man who inculcated his heirs, including also future Emperor Go-Yōzei (1571–1617), with a love for poetry, calligraphy, and other cultural pursuits. From infancy Sonchō was already elected to be a prince-monk at Shōren’in, as was customary for princes who were not in direct line for imperial succession. Shōren’in, founded in 1150, was a subtemple of the Enryakuji, the main headquarters of the Tendai sect that sat atop Mount Hiei, protecting the imperial capital of Kyoto from the northeast, the direction from which evil was thought to ensue. Shōren’in was a monzeki temple, at which imperial princes would study from an early age. For three-hundred years, the Shōren’in was a center for the study of Japanese court calligraphy.

From an early age Sonchō was appointed as abbot of Shōren’in. When Enryaku’in was increasingly under threat because of its resistance to the military, Sonchō took refuge at Danzan Jinja, a Shinto-Buddhist complex atop Mount Tōnomine in Nara. Sonchō was later among those who watched in horror as the great monastic complex of Enryakuji was set on fire by Nobunaga’s troops in 1571. Three years after its destruction, Sonchō returned to Kyoto to become abbot of Enryakuji in order to assist in the rebuilding of the revered Tendai sect headquarters.

Sonchō, who had studied the orthodox wayō (Japanaese-style) calligraphy of the Shōren’in Prince Sōn’en (1298–1356) through works passed down through the generations, left his mark on the history of traditional Japanese style calligraphy by becoming a teacher and dedicating his life to its study and promotion by creating treatises such as the Manual of the Inkstone Well (Bokuchi shōfu) and Oral Traditions of Calligraphy (Jubokudō kuden). During the 1590s, at Shōren’in, Sonchō became a mentor to many of the top calligraphers of the age, most notably Hon’ami Kōetsu and Shōkadō Shōjō, though the former arrived relatively late in his career, at age thirty-eight, and already had formulated his own more individual style. Shōkadō was clearly more strongly influence by the orthodox courtly styles advocated by the Shōren’in tradition, though he too broke conventional norms.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.