Glimpses of Joy and Sorrow in Chen Hongshou's Calligraphy Album

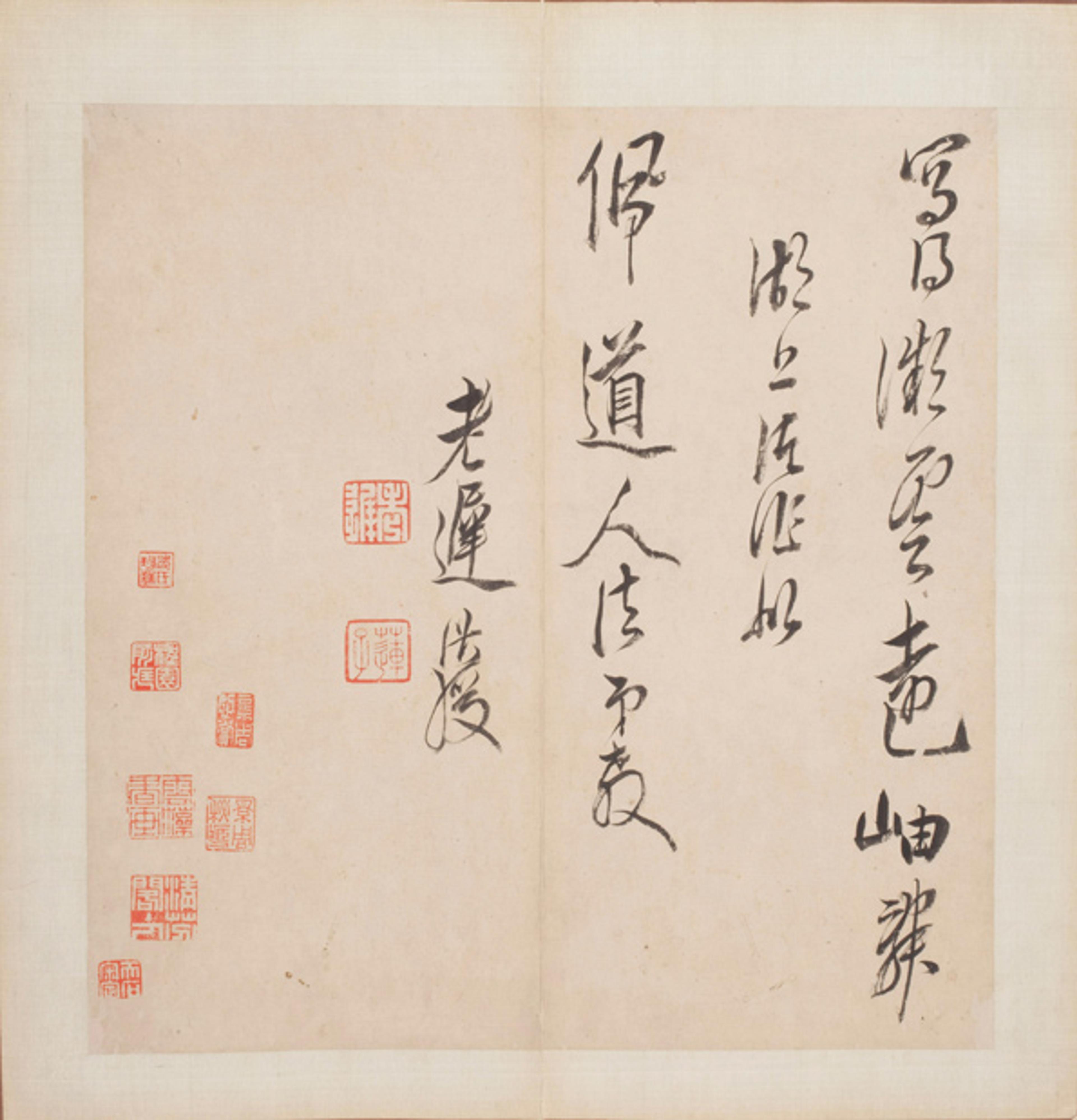

Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). Poems in semicursive script, Leaf 16, undated. Album of sixteen double leaves; ink on paper; 12 1/2 x 12 1/8 in. (31.8 × 30.8 cm). Lent by Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

«Calligraphy is considered the premier art form in Chinese culture because it so directly reflects an artist's character and mentality. Sequences of lines and dots trace the creative process with utmost immediacy, and one can envision the movements of the calligrapher's hand and sense his mood, while the words—especially poetry of one's own composition—convey his thoughts. The calligraphy album of Chen Hongshou (1599–1652), currently featured in the exhibition Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy—Selections from the Collection of Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang, exemplifies this unique union of visual and verbal arts.»

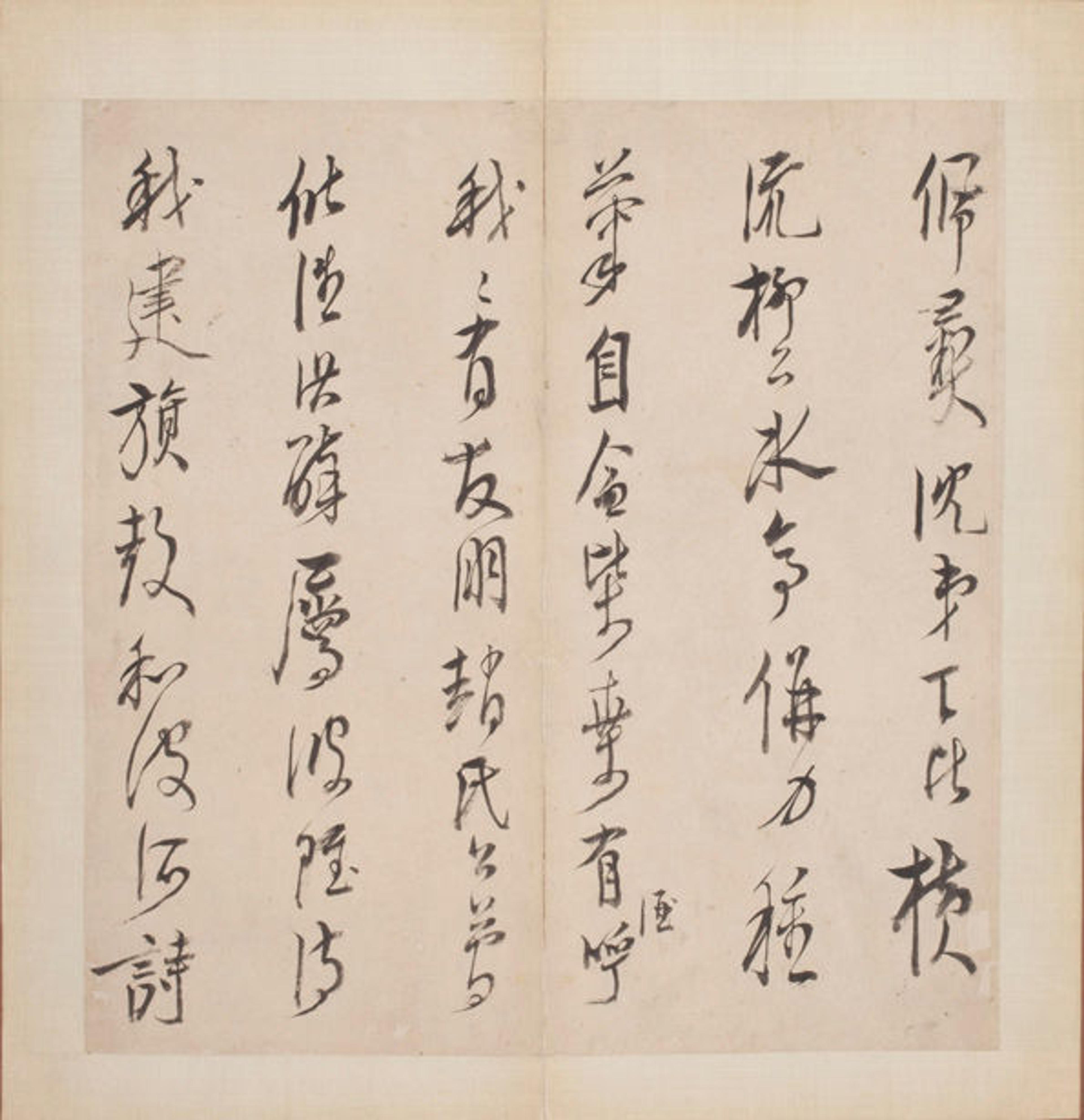

Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). Poems in semicursive script, Leaf 1, undated. Album of sixteen double leaves; ink on paper; 12 1/2 x 12 1/8 in. (31.8 × 30.8 cm). Lent by Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

One of the greatest artists in Chinese history, Chen Hongshou is most celebrated for his paintings of eccentric, stylized human figures, but his calligraphy is equally original. This album, a transcription of his own poems dedicated to a friend, is among the best of his late works. As he quickly pressed, lifted, and twisted a long, slender brush made of resilient animal hair, angular turns, pointed hooks, and sharply slanting diagonals were interwoven into flowing and spirited graphic imagery. The crisp lines feel taut and tense, and the characters stand tall and lean, often with a top-heavy configuration that disregards standard structural stability. The distinctive style points to an individualist comfortable with both his emotions and idiosyncrasies.

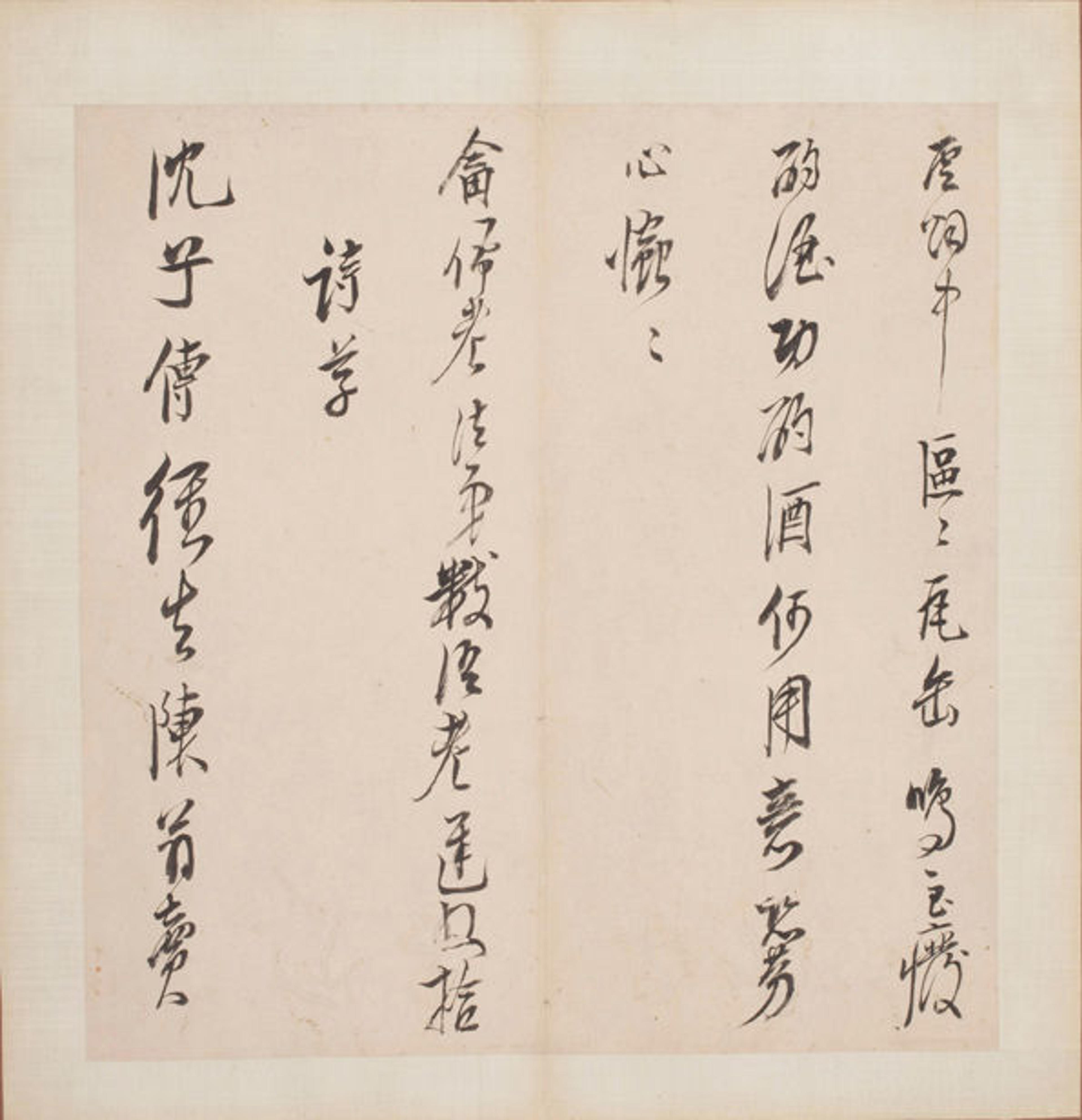

Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). Poems in semicursive script, Leaf 13, undated. Album of sixteen double leaves; ink on paper; 12 1/2 x 12 1/8 in. (31.8 × 30.8 cm). Lent by Guanyuan Shanzhuang Collection

An aesthete with a weakness for wine and women, Chen Hongshou could write beautifully, with a distinct sense of abandon. However, this album of twenty poems has a formal feel to its structure. The first poem, a preface composed in the antique mode of four-character lines, tells how the album originated during a gathering of friends who exchanged poems between toasts of wine. Chen named the recipient, Shen Yaozhang (1610–1666), in the opening line. Although he wrote in the semicursive script, which often generates linkage between characters in the fluid manner of writing, only rarely does it occur here; the columns remain straight and evenly spaced throughout all sixteen leaves. Chen's calculated organization and uncharacteristic restraint reveals a seriousness of intent.

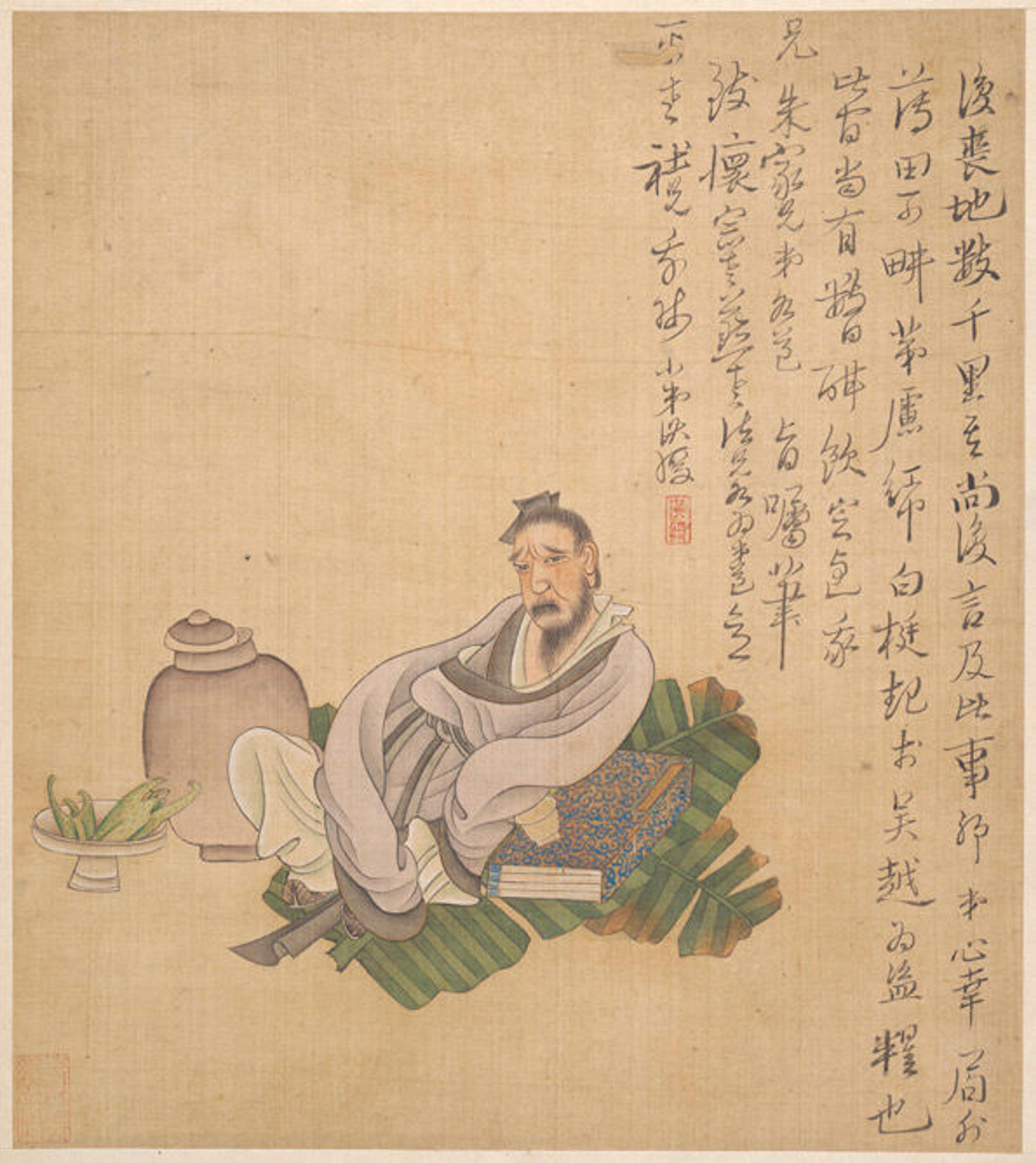

Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). Self-Image, Leaf A, undated. From Figures, Flowers, and Landscapes, 17th–18th century, one leaf dated 1627. Album of eleven paintings; ink and color on silk; average: 8 3/4 x 8 9/16 in. (22.2 x 21.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wan-go H. C. Weng, 1999 (1999.521a–k)

Although the album is not dated, references to both the West Lake and his refuge in the mountains suggest that Chen Hongshou created it in Hangzhou after moving there in February 1649. A recurring theme of the poems is the trauma of dynastic change in 1644, when the alien Manchu people conquered China. Most devastated by this catastrophe were the educated elite, to which both Chen Hongshou and Shen Yaozhang belonged. Chen descended from an eminent scholarly family near Shaoxing, Zhejiang Province, and, after losing all family property during the Manchu conquest, became a professional artist. For more profitable business, he moved to Hangzhou and soon befriended local scholars like Shen, who were still devoted to the vanquished Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The loyalist sentiments of both the artist and recipient—solemn affinities not to be trivialized—may account for the unusual formal structure of the album.

The album begins with a drinking party in which an aged Chen Hongshou and friends drown their sorrows while enjoying nature and poetry. As emotional outbursts felt during the conquest in previous years had ebbed, subdued anguish began to reverberate through the poems, together with meditations on carnal desire and life's vicissitudes. What brings a closure to these revelations of Chen's post-conquest mentality are two ballads that recall the carefree days of his youth in the company of courtesans. One of them—his best-known poem—reads:

Riding a red-spotted white horse was Dong, the flying fairy.

With a piece of raw silk that she prepared herself, she begged me for a lotus painting.

Joyous moments tend to stay long in memory.

It was in front of General Yue's grave in the third month of the gengshen year [1620].

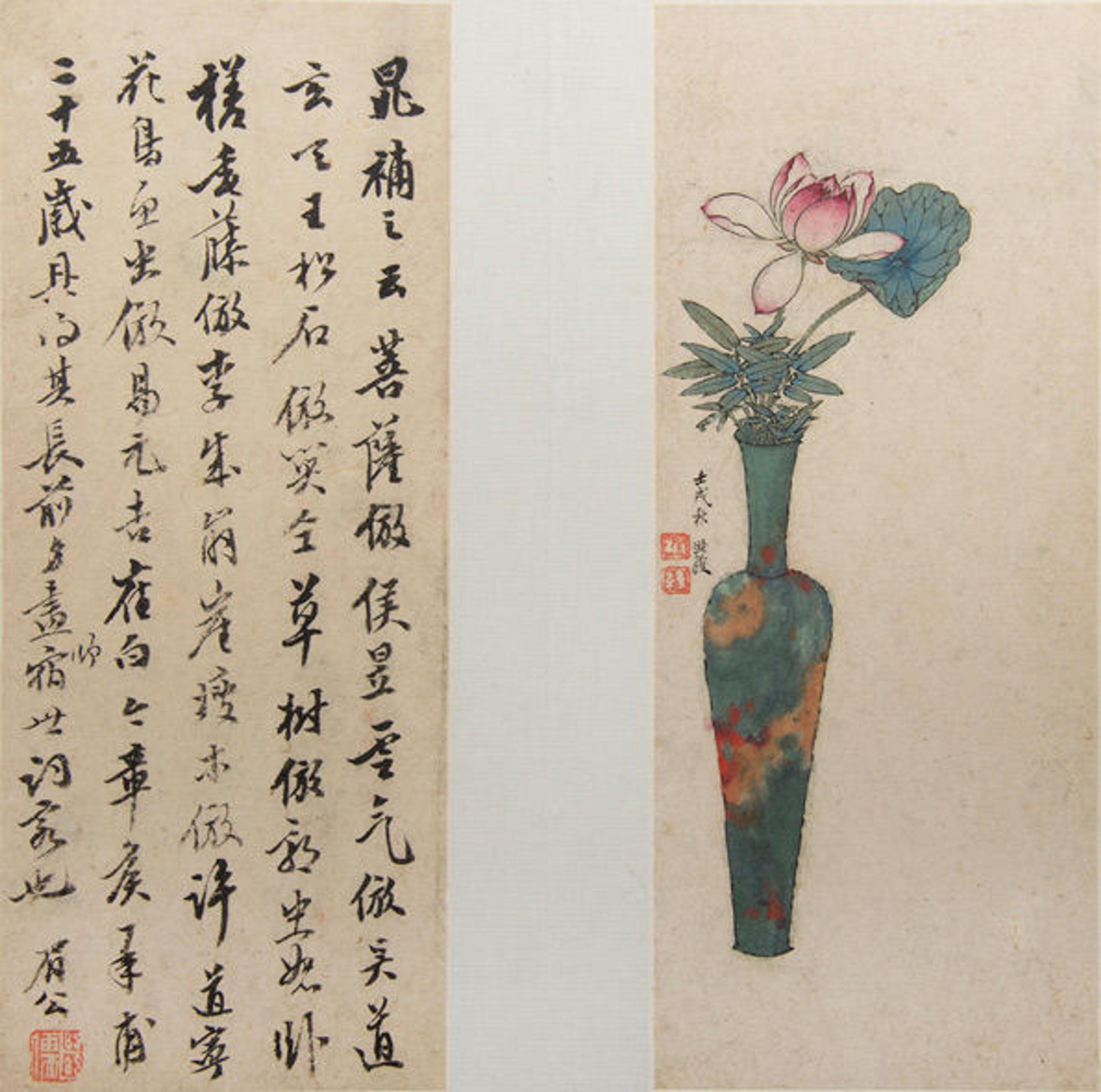

Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). Lotus and Bamboo in a Vase, Leaf L, dated 1622; facing page inscribed by Chen Jiru (Chinese, 1558–1639). From Landscapes, Figures, and Flowers, dated 1618–1622. Album of twelve paintings; ink and color on paper; each leaf: 8 3/4 x 3 5/8 in. (22.2 x 9.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Far Eastern Art Gifts, 1985 (1985.121a–l)

Shi-yee Liu

Shi-yee Liu is an assistant research curator of Chinese art in the Department of Asian Art.