Sruti Upanga

19th century

Not on view

The sruti upanga is a bagpipe that was historically played throughout Southern and Central India (Day 1891, Sonnerat 1782:102). In line with its name (‘sruti’ means ‘drone - not to be confused with the sruti, a type of double reed shawn also from India), it was used as a drone accompaniment. The holes on the drone would be partially or completely plugged with wax to obtain the desired tone (Day 1891:Plate XVI). This bagpipe – also called bhazana sruti (Day 1891:Plate XVI), tourti (Sonnerat 1782:102), or titti in Andhra Pradesh (Roghair 1982:33) – was played in a range of settings.

In Tamil Nadu, the sruti upanga was used within an ensemble of musicians, who accompanied the devadasi. Devadasi, whose name means ‘servant of God’ were female dancers who were dedicated to a deity in a local temple. Devadasi practiced Indian classical dancing, both within the temple and in private celebrations. Their singing and dancing were accompanied by male musicians, who were from a different household to theirs, but were from the same community or hereditary lineage of temple musicians (Srinivasan 1985). A range of percussion, string, and wind instruments were used in these temple and community settings, with the bagpipe (sruti upanga) serving as the drone. Eighteenth century Company paintings from Madras (now known as Chennai), commissioned by the British to illustrate life in India, were painted by Indian artists and regularly included bagpipes in illustrations featuring the devadasi and their musicians. Many of these are labelled as Nautch dancers, an anglicized term derived from the Hindustani ‘nāch’ (dance). The simplification of the devadasi’s activity to ‘dance’ reduced their complex role in society, and contributed to an anti-nautch campaign that not only portrayed devadasi as temple prostitutes (Meduri 2018:303). This led to the ‘Madras Devadasis Prevention of Dedication Act’ 1947, effectively putting an end to the practice, as the women were disempowered and became unable to earn a living (Srinivasan 1985:1869). It also endangered Classical Indian dancing, which had been until then the hereditary knowledge of the devadasi. In order to counteract this, this practice was rebranded as ‘Bharatanatyam’ and was taken up by middle class women, thus placing it in a more acceptable social frame (ibid.)

The drone bagpipe in Devadasi contexts was still in use at the turn of the 20th century, as evidenced by late 19th century photographs (cf. the reproduction in Hutchinson 1901). They were probably replaced by the sruti box in the early 20th century, as it became popularized throughout India.

While the sruti upanga disappeared in Tamil Nadur in the early 20th century, in Andhra Pradesh (Central India), the sruti upanga (or titti) was still in use in the early 1980s, as evidenced by Roghair’s monograph published in 1982 (plates 2-3). Here, the bagpipe was also used a drone instrument used to accompany Telugu epic singers (Roghair 1982:33). The drone pipes, made out of a goatskin and bamboo pipes, provided the background note for a regulated musical ensemble of drums (pamdajōḍu), finger cymbals (tāḷamu) accompanying the narrative singer, the Vῑra Vidyavantulu (ibid.). These epics could take up to thirty days to complete, with each story or section lasting about an hour, providing a rationale as to why a bag-based drone rather than one created through circular breathing, might have been a preferred option.

(Cassandre Balosso-Bardin, 2023)

Technical Description

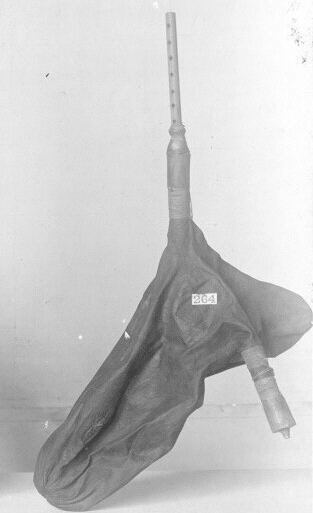

Single cane drone, 7/0 holes, cylindrical bore, 22 cm. Held in stock with cloth and hemp and made airtight by wax sheath.

Cane insufflation pipe (without valve) waxed into large stock, protruding 7.6 cm.

Hand carved cane cylindrical stocks.

Goatskin bag, approx. 54 cm long, with neck and hind end tied off inside and having stocks in forelegs.

References

Day, Charles Russell, 1891. The music and musical instruments of southern India and the Deccan. London & New York: Novello.

Hutchinson, Henry Neville, John Walter Gregory, and Richard Lydekker, 1902. The Living Races of Mankind: A Popular Illustrated Account of the Customs, Habits, Pursuits, Feasts and Ceremonies of the Races of Mankind Throughout the World. Vol. 1. Appleton

Meduri, Avanthi, 2018. "Interweaving dance archives: Devadasis, Bayadères, and Nautch girls of 1838." Movements of Interweaving. New York: Routledge. 299-320

Roghair, Gene. H. 1982. The Epic of Palnadu: a sturdy of Palnati Virula Katha, a Telagu Oral Traditional from Andhra Pradesh, India. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Sonnerat, Pierre, 1782. Voyage aux Indes orientales et à la Chine. Tome premier. Chez l’Auteur

Srinivasan, Amrit, 1985. Reform and Revival: the Devadasi and her Dance. Economic and Political Weekly, 30(44):1869-1876.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.