Seated Figure

Not on view

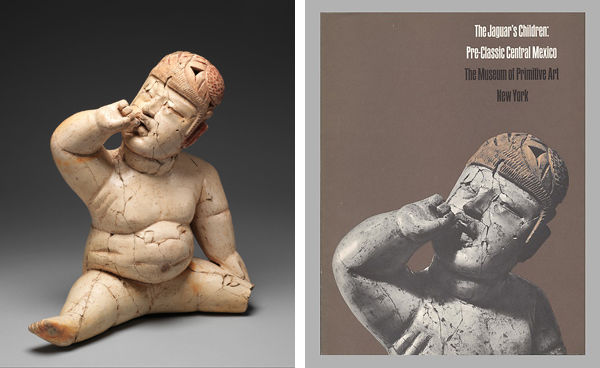

This seated figure likely represents an infant gazing upward and raising its right hand to its mouth. The artist of this baby worked in a fine, white clay to produce a hollow figure subsequently decorated with a white slip and red pigment. Without marked gender and seated with splayed legs and its hands on its thighs, the figure has the posture, body proportions, and fleshiness of a human baby, though symbolic designs embellishing its body and a distinctive headdress distinguish it from a mere mortal.

This pudgy figure is one of the best examples of this class of human figures displaying characteristics of well-fed children, the so-called Olmec “babies.” The body of the baby was careful modeled to indicate realistic folds of skin and subcutaneous fat, evoking themes of abundance and plentiful resources. The face displays non-mortal characteristics, such as the stylized eyes, downturned mouth, and squared ears. The left portion of the figure’s back contains iconographic elements, such as crossed bands and crosshatching, possibly representing tattooing or scarification. This example is distinguished by its elaborate headpiece colored red-pink with powdered cinnabar and red ochre, that was probably used to anoint the tomb in which this figure was placed.

The babies share some iconographic and stylistic characteristics with the monumental sculpture from the Gulf Coast Olmec centers of San Lorenzo and La Venta, but seem to have only been produced during the earlier Olmec florescence between about 1200 and 800 B.C. This figure is reported to be from the central highland site of Las Bocas, in the Mexican state of Puebla, where a number of Olmec-style ceramic objects have been found. Others have been found in burial contexts at the sites of Tlapacoya and Tlatilco, in the Basin of Mexico near modern-day Mexico City. Researchers encountered a well-known pair of sculpted individuals—nicknamed “the twins”—in Burial 12, Offering 6, at Tlatilco, which share many characteristics with the hollow, baby-face figurines.

Supernatural infants play a significant role in Olmec art. These could be portraits of elite babies, infantilized portraits of actual individuals, idealized portraits of deities or mythological characters, or some other type of ritual agent. They could be memorials to infants that left this world too early, or representative emblems of whole lineages. The Olmec peoples may have been preoccupied with child-rearing and the mythological connections between the life cycles of infants and agriculture. In some cases, the ceramic effigies may have served as substitutes for actual infants in a sacrificial or dedicatory ritual, as there is compelling evidence of Olmec infant sacrifice or ceremonial burials. Mexican researchers working at the extraordinary waterlogged site of El Manatí (“the manatee”) found dismembered bones of newborns, perhaps neonates, and a primary infant burial in the fetal position. These were associated with miraculously preserved wooden busts, rubber balls, and greenstone ax caches. The faces of the wooden busts are evocative of similar expressions found on the ceramic babies.

Further reading

Benson, Elizabeth P., and Beatriz de la Fuente, eds. Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1996.

Berrin, Kathleen, and Virginia Fields, eds. Olmec Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico. Los Angeles: LACMA, 2010.

Blomster, Jeffrey. "Context, Cult, and Early Formative Period Public Ritual in the Mixteca Alta: Analysis of a Hollow-Baby Figurine from Etlatongo, Oaxaca." In Ancient Mesoamerica 9 (2) (1998): 309–326.

Blomster, Jeffrey. "What and Where Is Olmec Style? Regional Perspectives on Hollow Figurines in Early Formative Mesoamerica." In Ancient Mesoamerica 13 (2002): 171–195.

Castro-Leal, Marcia. "The Olmec Collections of the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City." In Olmec Art of Ancient Mexico, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson and Beatriz de la Fuente, 139–143. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1996.

Clark, John E., and Mary E. Pye, eds. Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2000.

Coe, Michael D. The Jaguar's Children: Pre-Classic Central Mexico. New York: Museum of Primitive Art, 1965.

Coe, Michael D., ed. The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership. Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 1996.

Covarrubias, Miguel. Indian Art of Mexico and Central America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957.

Ortiz, Ponciano, and Maria del Carmen Rodriguez. "The Sacred Hill of El Manati: A Preliminary Discussion of the Site's Ritual Paraphernalia." In Olmec Art and Archaeology in Mesoamerica, edited by John E. Clark and Mary E. Pye, 75–93. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2000.

Pillsbury, Joanne. "The Pan-American: Nelson Rockefeller and the Arts of Ancient Latin America." In The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 72, No. 1 (2014): 18–27.

Pool, Christopher A. Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Tate, Carolyn. Reconsidering Olmec Visual Culture: The Unborn, Women, and Creation. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012.

Taube, Karl. Olmec Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 2004.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.