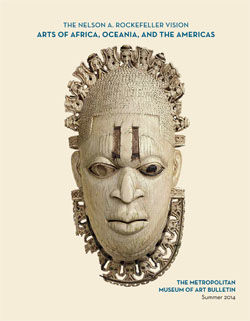

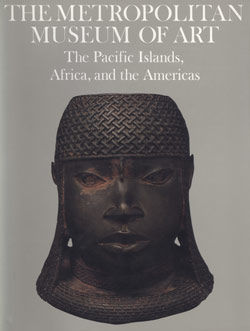

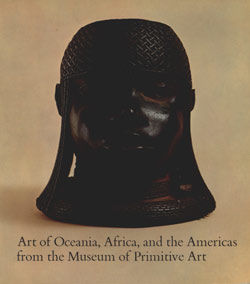

Sculptural Bust from a Reliquary Ensemble (The Great Bieri)

Not on view

In Fang society, figurative sculptures produced for the ancestor cult, or "Bieri," were designed to complement reliquary containers. Such works were generalized ancestral representations which were memorialized and addressed in times of need through relics preserved in the attached container. This sculptural creation distills the representation of a larger-than-life ancestral presence to a head with a penetrating gaze. It was originally placed at the summit of a portable family altar that held precious relics of at least nine generations of an extended lineage. While the relics were accessible to only initiated family members, the sculptural element visually summarized the importance of the contents. The black of the wood was enlivened with applications of palm oil that preserved the sculpture and enhanced the play of light on the surface. Historically, Fang sculptors created free-standing heads, half-figures, and full-figures to be integrated into bieri altar ensembles.

In 1962, reflecting upon the significance of this work, art historian Robert Goldwater observed, "For every style and every period, in the history of the arts of mankind, a few works stand out above the rest. Somehow they both contain and surpass all these qualities which we value in the art of the culture from which they come. They seem to have captured the ideal of design and expression toward which many artists tended… The Great Bieri is such a work: it is the embodiment of Fang sculpture, and one of the great classics of African art."

This majestic work is among the most frequently reproduced works of African art. Its impact derives from its bold hierarchic presence, which has been rendered on a monumental scale. While The Great Bieri is the largest of the known Fang heads, it is also the most formally succinct and pared down. Its author has masterfully distilled the genre to its essential elements through gently equilibrated curved lines. So that the astonishing breadth of the domed forehead does not overpower the narrow eroded chin, a band of hair extends at either side of the head. These vertical extensions are broadened and enlivened at successive intervals by the added features of the inverted C-shaped ears and two cylindrical rolls. A third, broader tress falls from the crown of the head down the back. The penetrating omniscient gaze is directed outward from the circular metallic disks of the eyes, framed by lightly incised curved brows; the vertical nose is squared at the base. On the inky black surface of the face, there are highlighted passages of oil residue. On the reverse side, areas of the patina have worn away to expose the underlying rich red-brown wood. The abrasion and wear at the base of the face, across the mouth and chin, occurred through ritual handling. A vertical split reaches from the summit to the chin.

This icon has been a muse to artists both in the West and beyond since the early twentieth century. The first person to whom its ownership has been attributed was the Chilean poet and founder of the Creacionismo movement, Vicente Huidobro. In 1916 Huidobro settled in Paris, where he established contacts with such members of the avant-garde as the artists Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Francis Picabia, and Jacques Lipchitz and the writers Blaise Cendrars and Guillaume Apollinaire. He appears to have acquired this work shortly after his arrival in Paris and in 1918 was inspired to write the poem Ecuatorial, dedicated to Picasso, which reflected this embrace of Cubism in poetic expression – and specifically of this work from equatorial Africa as his muse. Like his counterparts in the visual arts, Huidobro did not refer overtly to the imagery of the African sculptures he collected, but rather identified powerfully with what he saw as their ideal blending of representation and abstraction.

Huidobro subsequently relinquished this epic creation to French art dealer Paul Guillaume, who in turn sold it to British-American artist Jacob Epstein by the late 1920s. Epstein recalls his earliest encounter with Guillaume: "When I was in Paris in 1912, I saw an advertisement in a colonial paper asking for African carvings in hard wood. Calling at the address in Montmartre I met Paul Guillaume for the first time, in a small attic room. He started the vogue in African work." Epstein’s collection was sold after his death in August 1959. Before its dispersal at auction, Goldwater acquired in 1961 four of the works for the Museum of Primitive Art in New York – a privately owned museum whose holdings were later transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and founded the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

The Great Bieri’s formal qualities evoke one of Epstein’s statements concerning the eloquence of African sculpture: "In much of the work there is real anatomic truth to be found, extremely simplified, and often expressed architecturally." Epstein further comments on the keen powers of observation manifested in the heads carved by Fang masters: "These heads are realistic works, obviously the result of a very minute study of nature. You can see the well-developed bony structure of the forehead, the sunken eyes, protruding jawbone and the flesh around the mouth and nose shrinking, as if to crumble away. They are burial symbols."

Further reading

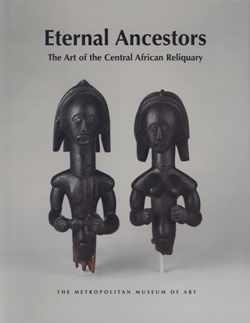

LaGamma, Alisa Ed. 2007 Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Perrois, Louis. Fang. Visions d’Afrique. Milan: 5 Continents, 2006

Exhibition history

"La grande peinture contemporaine à la collection Paul Guillaume." Bernheim-Jeune, Paris. May 25-June 27, 1929

"Primitive African Sculpture." Lefevre Galleries, London. May, 1933

"African Negro Art." The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 1935

"Arte in Africa." Centro di Studi di Storia delle Arti Africane, Florence. March 15-18, 1984

"'Primivitism' in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern." The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas. 1984

"La Grande Scultura dell'Africa Nera." Forte di Belvedere, Florence. July 15-October 29, 1989

"Perfect Documents: Walker Evans and African Art, 1935." Metropolitan Museum of Art. February 1-September 3, 2000

"Arts d'Afrique." Musée Dapper, Paris. November 30, 2000-June 30, 2001

"Eternal Ancestors: the Art of the Central African Reliquary." Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2, 2007-March 2, 2008

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.