Figure from a Reliquary Ensemble: Seated Female

Not on view

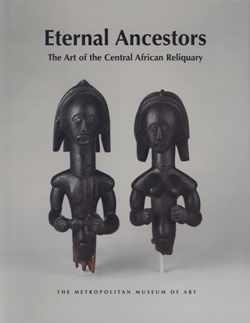

The Fang peoples derive a sense of continuity with their past as well as a communal cohesiveness in the present through an ancestral cult known as bieri. Bieri reliquary figures, such as this 19th century example, embody the qualities that the Fang admire most in people—namely, tranquility, vitality, and the ability to hold opposites in balance. Such wooden figures and heads are placed on top of bark containers that hold the precious relics of important clan ancestors. The carved head or figure mounted on top of the reliquary box guards the sacred contents against the forbidden gaze of women and uninitiated boys. Before being removed from Africa, such works were invariably separated from the relic containers that they originally enhanced.

This formidable female figure personifies controlled exuberance. Despite her contemplative expression, her being exudes vitality and boundless physical dynamism. The eyes are defined as deeply incised pupils within expansive recesses. These concave passages are echoed in the round at the summit of the forehead by the bold globular projections of the coiffure elements. This regal and original arrangement of hair is highly detailed. Several contiguous crests extend across the crown of the head and are gathered in a single vertical tress at the nape of the neck.

The Fang sculptor, who lucidly articulated this figure as a series of discrete component elements, integrated them masterfully into a seamless form to stunning effect. The pronounced ovoid volume of the head is abruptly juxtaposed with the broad columnar neck. At the outer corner of each eye a deep arc extends to the bridge of the nose. The nostrils are slightly flared, and the open mouth is cast as a broad oval. Especially alluring is the effect of the shimmering highlights that glance off the luminous midnight black wood, which is thoroughly saturated with oil. Another arresting visual accent is provided by the pendent oval breasts. These do not appear as sensuous elements but rather as overt attributes of power. Their formal definition complements the muscular curves of the physiognomy, so that they are echoed in the successively larger cylindrical units of the shoulders, upper arms, and fore-arms. The arms are bent at the elbows, hands held in front of the body in a pose suggesting arrested animation.

Positioned as freestanding with slightly flexed knees, the figure appears to shift her weight slightly to the proper right side. The fact that she was originally conceived as seated is apparent from the extreme abbreviation of the powerful thighs, when seen frontally, in contrast to the full forms of the elongated calves. On the reverse side the vertical channel of the spine extends the length of the back and intersects with the horizontal passage of the buttocks. The original patrons sought to repair a break to the proper left shoulder b affixing horizontal metal bands with five nails to the front and reverse side. Two brass rings appear around the neck as well as one around the proper left wrist and each ankle.

This work was owned successively by two members of the Western avant-garde, André Derain and Jacob Epstein. According to legend, Derain acquired his first work of African sculpture, a Fang mask, from his friend and close associated Maurice de Vlaminck. Around that time, he went to London and studied the ethnographic collections of the British Museum. That transforming experience led him to write Vlaminck of the "amazing, disquieting" impact of the works he encountered. Art historian Jack Flam has noted that despite this emotional response to African sculpture, Derain strove to grasp the key to its inherent formal logic.

Flam has proposed that Vlaminck was principally drawn to and identified with African art’s instinctive expressive qualities. He has further noted that, although Vlaminck did not extensively appropriate the formal qualities of such works in his own painting, he was eager to establish his own seminal role in the avant-garde’s "discovery" of African art. By Vlaminck’s account, the experience that ignited his own interest occurred in a bistro in Argenteuil, while taking a break from painting outdoors. Three African artifacts on a shelf behind the bar caught his attention, and he acquired them in exchange for buying the house a round of drinks. Shortly afterwards, a friend of his father gave him three more works. Among these was a Fang mask that he hung in his bedroom. Upon seeing the mask, Derain asked to buy it from him, but Vlaminck initially refused. A few weeks later, in need of money, he relented and it entered Derain’s collection. According to Flam, these events, which may have occurred between 1903 and 1905, became the most frequently related narrative of the discovery of "primitive art."

Vlaminck’s insistence on his role in instilling in his contemporaries, such as Matisse and Picasso, an awareness of African art’s aesthetic qualities is underscored in another account he disseminated. According to a version related by his biographer Francis Carco, Vlaminck showed an African sculpture to Derain and said that he found it to be "almost as beautiful as the Venus de Milo." Derain responded that it was in fact "as beautiful as the Venus de Milo." The two then showed it to Picasso, who reputedly deemed it "more beautiful than the Venus de Milo."

Alisa LaGamma

Further Reading

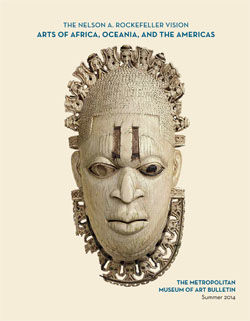

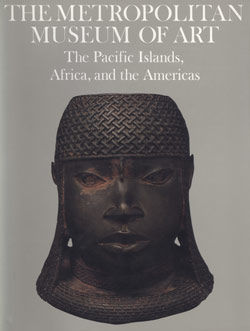

LaGamma, Alisa, ed. Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

Perrois, Louis. Fang. Milan: 5 Continents, 2006.

Exhibition History

"Exposition d'art Africain, d'art Océanien." Galerie Pigalle, Paris, 1930.

"The Epstein Collection of Tribal and Exotic Sculpture." Arts Council of Great Britain, London. 1960.

"Exhibition No. 22," The Museum of Primitive Art, New York, April 18 – July 1, 1962.

"First World Festival of Negro Arts." Dakar, Senegal, April 1-4, 1966.

"First World Festival of Negro Arts." Grand Palais, Paris, June 1-August 20, 1966.

"Art of Oceania, Africa and the Americas from the Museum of Primitive Art." The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. May 10-September 1, 1969.

"Masterpieces of Fifty Centuries." The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, November 10, 1970-June 1, 1971.

"'Primivitism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinities of the Tribal and the Modern." The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit; Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas. 1984.

"La Grande Scultura dell'Africa Nera." Forte di Belvedere, Florence, July 15-October 29, 1989.

"Eternal Ancestors: The Art of the Central African Reliquary." The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. October 2, 2007-March 2, 2008.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.