Powerful Beauty: Hatshepsut and Aphrodite

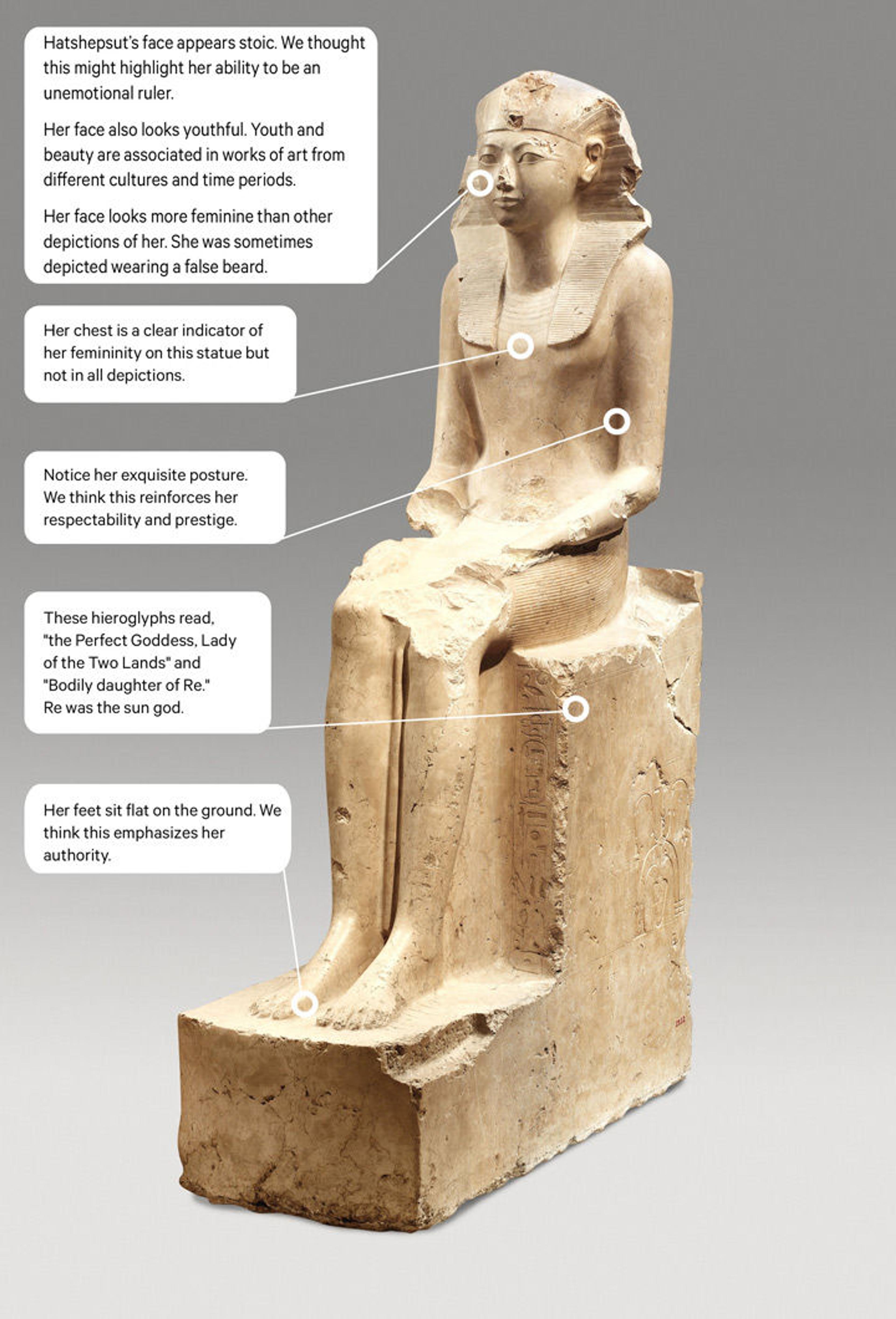

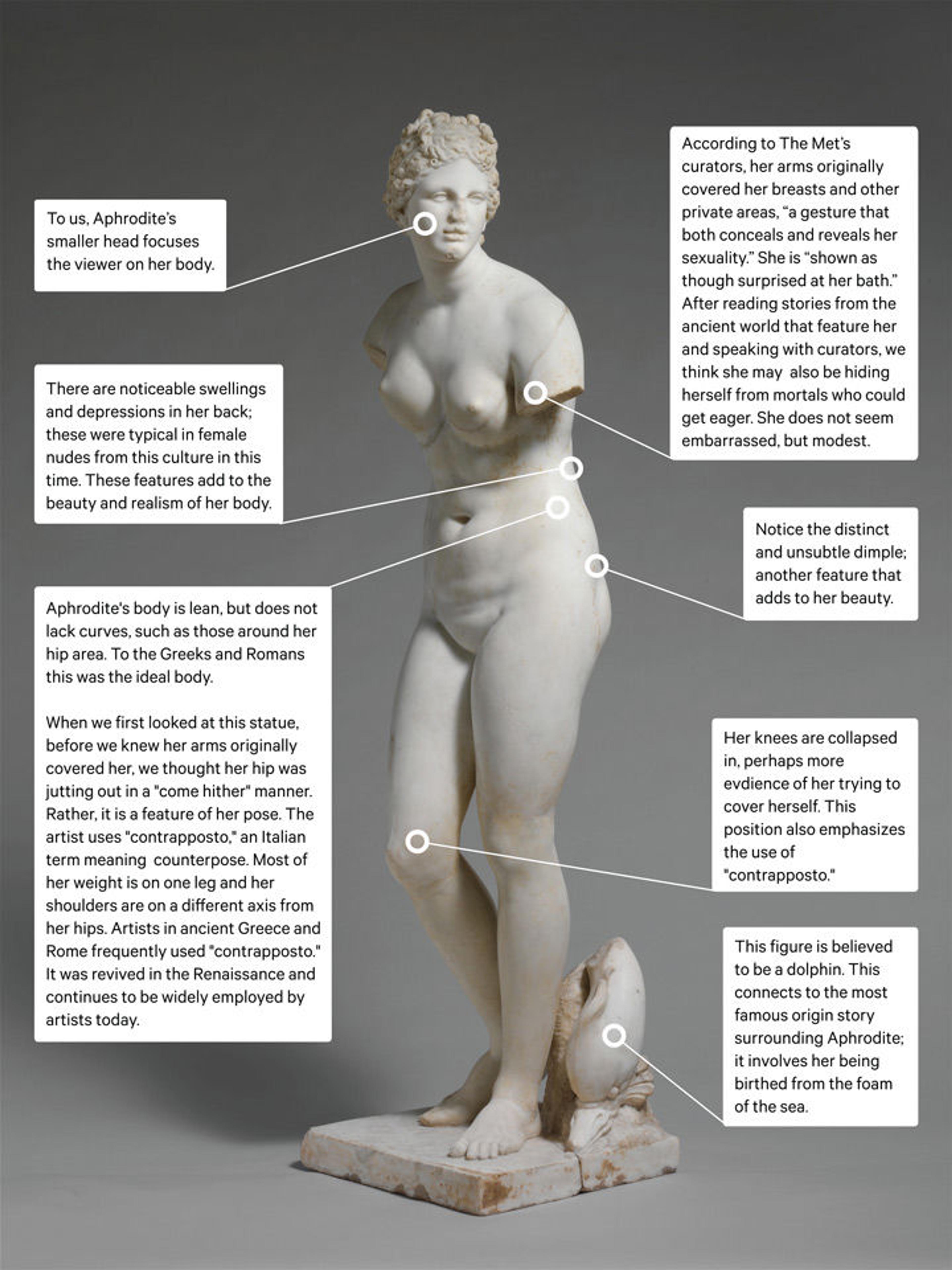

Seated statue of Hatshepsut. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III (ca. 1479–1458 B.C.). From Egypt, Upper Egypt, Thebes, Deir el-Bahri & el- Asasif, Senenmut Quarry, MMA excavations, 1926–28/Lepsius 1843–45. Indurated limestone, paint; H. 195 cm (76 3/4 in.); W. 49 cm (19 5/16 in.); D. 114 cm (44 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1929 (29.3.2). Right: Marble statue of Aphrodite, 1st or 2nd century A.D. Imperial. Marble; H. with plinth 62 1/2 in. (158.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1952 (52.11.5)

«While exploring The Met collection, we came across a seated statue of Hatshepsut that depicts the pharaoh as a powerful and confident ruler and a marble statue of Aphrodite that shows the goddess as being soft and demure. To us, both embody the notion that beauty is power in very different ways, so we highlighted details in both statues that show how powerful and beautiful they each were.»

Hatshepsut rose to power during a time when it was extremely abnormal for women to occupy positions of authority, and she was just as successful as male pharaohs who preceded her. She oversaw a large construction program throughout Egypt, including her own mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, and led her army to war on at least one known occasion. As we researched Hatshepsut, we felt her success might have stemmed from an adamant refusal to let anything prevent her from attaining what she wanted.

Due to the large span of territory she ruled and a lack of accessible communication during that time period, statues of Hatshepsut partly served as a way for her to relay her identity to the Egyptian citizens. It is interesting to note the way Hatshepsut is portrayed in the statues she commissioned during her rule. She asked the artists to depict her as less feminine by including the headdress, fake beard, and masculine garb that was traditionally worn by pharaohs. She did this not to disguise herself, but rather to signify that, although she was a woman, she commanded the same respect as a male pharaoh.

We can see the effort, time, and thought put into the precise construction of the seated statue of Hatshepsut; she exudes power. We pointed out some of the details that stood out to us.

Aphrodite, also known as Venus, is the Greek goddess of love. Stories from ancient Greece and Rome tell of her power over both gods and mortals, including the ability to make a person desire any person of her choosing. Stories about her describe her as the most beautiful of all the goddesses.

There is great power in Aphrodite's beauty. We highlighted the details in this marble statue of Aphrodite that reveal she was considered an ideal beauty.

We wondered how this type of beauty has presented itself in modern society, and started to notice connections between Hatshepsut and Margaret Thatcher, known as the "Iron Lady." As the first female prime minister of Britain, Thatcher played an integral role in ending the Cold War. She is remembered today as having governed with undeterred tenacity and a commitment to serving her people with passionate resolve. It was unusual for both Hatshepsut and Thatcher to have high positions of power, and both defied the typical beauty standards of women in their time. In contrast, the statue of Aphrodite embodies the sort of seductive side of beauty that one might see in a perfume ad today: a nude woman covering herself just so much as to conceal her breasts while a man longingly gazes at her. We did not find this sort of beauty to be especially empowering, though we admit it has a sort of power.

The seated statue of Hatshepsut and the marble statue of Aphrodite are representations of two different types of powerful beauty. Despite their differences in appearance, to us, both figures exude power. Though we do not necessarily support all of what they did in their respective times, we find the feminine power they convey to be an important kind of beauty we hope persists and continues to defy the accepted standards of beauty.

Erin undefined

Erin was formerly a high school intern with the Museum's High School Internship Program.

Livvy undefined

Livvy was formerly a high school intern with the Museum's High School Internship Program.

Priya undefined

Priya was formerly a high school intern with the Museum's High School Internship Program.

Ron undefined

Ron was formerly a high school intern with the Museum's High School Internship Program.