Intern Insights: A Summer of Study and Exploration

From Elizabeth Perkins, Assistant Museum Educator, Academic Programs:

«Interns in the Museum Seminar (MuSe) Program come to the Met every summer to gain practical experience and learn about critical issues surrounding museum practice and interpretation. They work closely with supervisors in departments across the Museum on special or ongoing projects, while also researching and leading public tours across the galleries. This summer, recent college graduates Alexandra McKeever (Smith College) and Kate Justement (Auburn University) worked in the Department of Islamic Art, where they partnered with curators to gain some hands-on experience with collection objects and archives.»

Drawing What You Can't See

by Alexandra S. McKeever

A selection of bowls from the Met's collection excavated from Nishapur, Iran. All photos courtesy of the author

During my internship at the Met, I have been working with a collection of ceramics from Nishapur, Iran. These brightly colored ceramics, dating from the tenth and eleventh centuries, are from an excavation the Met carried out in the mid-1930s and 1940s. My task has been to render archaeological drawings of each bowl, plate, and fragment.

I had never performed this type of work before I got to the Met. My previous archaeological drawing experience had involved drawing stratigraphy (earth layers) at a particularly rainy dig on the Isle of Man, where the most difficult part of the project was trying to distinguish between layers of mud. Archaeological drawings of ceramics, as I found out, are a little more complex, as it involves more than just drawing the object. You have to draw the cross section, or what the object would look like cut in half, and since cutting ancient artifacts in half is not an option, you draw what you can't see by extrapolating from what you can see.

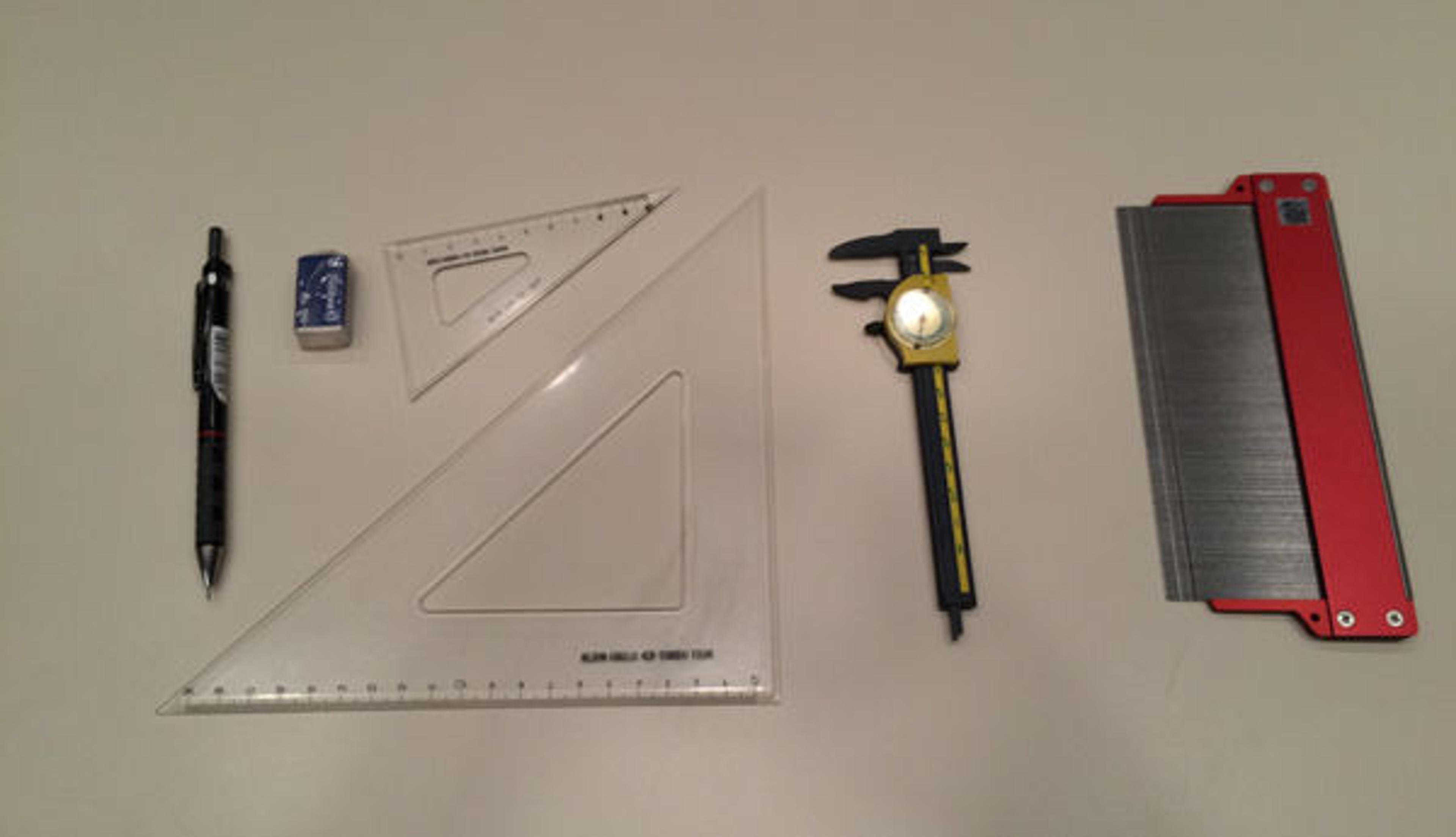

Tools of the trade for archaeological drawing (left to right): pencil, eraser, right triangles, caliper, profile gauge

In order to visually reconstruct these ceramics, illustrators use a number of tools: rulers, right triangles, calipers, and profile gauges. First I take measurements of the base, rim, and height of the object, which is a more difficult process than you would think because these handmade ceramics are often lopsided, making it hard to get precise measurements of diameters and heights. I then use these measurements to draw top, bottom, and middle lines, and only then can I trace the outside of the object using a profile gauge, a metal comb with teeth that slide back and conform to the object pressed into them.

By pressing the objects into the gauge and then tracing the resulting shape on paper, I am able to realize the profile shape of the object. After doing the same with the inside and the bottom of the object, I can construct the whole shape. I then check the thickness with a caliper, and this is usually when I realize something might need to be redone. If the thickness doesn't match up, I have to reposition the lines I traced.

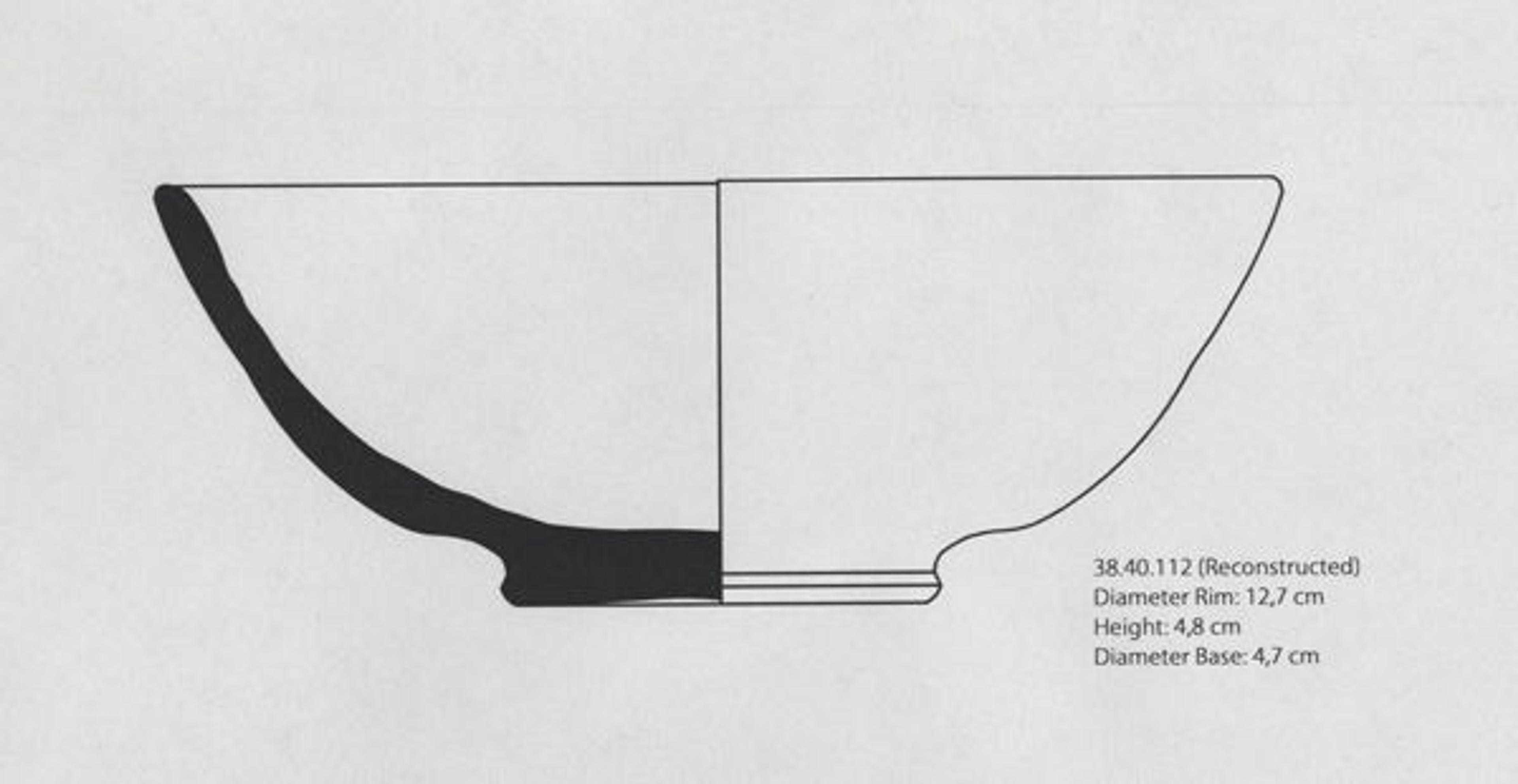

A green glazed bowl with incised decoration from the collection and its profile taken with a profile gauge

Once I have the cross section, I scan the image into the computer and use illustration software to trace and flip the image. Flipping the outside line gives me the profile—what you see when looking at the object—and the archaeological illustration is complete. Having these archaeological drawings makes it easier for researchers to study the collection.

Finished archaeological illustration of the green glazed bowl

While I am extremely careful at all times, the Met has special protocols in place to protect the objects. When I need to collect more objects to draw, I coordinate with one of the technicians to visit the Department of Scientific Research and pick them up. I love going to Scientific Research because I get to see what people are working on down there, which includes everything from African sculptures to Islamic tiles. One of the wonderful parts of getting to work with the ceramics is knowing that I am handling the same bowl or dish that someone touched one thousand years ago. This tangible connection to the past is an incredible feeling.

The greatest thing about being an intern at the Met is seeing and hearing about the amazing and varied projects people here are working on. I have discovered and learned something new every day—whether I am wandering around the galleries, hearing about what other interns are doing, or talking to staff members about their work. I love working in a place where I am constantly learning, and I hope to continue working in the challenging and inspiring museum field.

Excavating an Archaeologist: The Ernst Herzfeld Papers

by Kate Justement

Sketchbook: pocket folder 2; page 5. Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

I have had the great privilege this summer to work in the Department of Islamic Art as a MuSe Intern, the majority of which I have been working with the Ernst Herzfeld Papers. Herzfeld (1879–1948) was a famous German archaeologist, historian, and philologist who worked on the development of ancient Near Eastern studies at a variety of excavations, including Samarra and Kurdistan (Iraq), Damascus and Aleppo (Syria), and Persepolis (Iran).

The Herzfeld collection is unique in that they are split between two different institutions: part of them reside in the Smithsonian Institution's Freer and Sackler Galleries, while the rest have a home here at the Met. Within the large project of digitizing and creating online records for the Museum's portion of the Herzfeld papers—which will not only facilitate researcher access and use, but also provide a more comprehensive picture of Herzfeld as a scholar—my duties have included a variety of cataloging, archival, and research tasks.

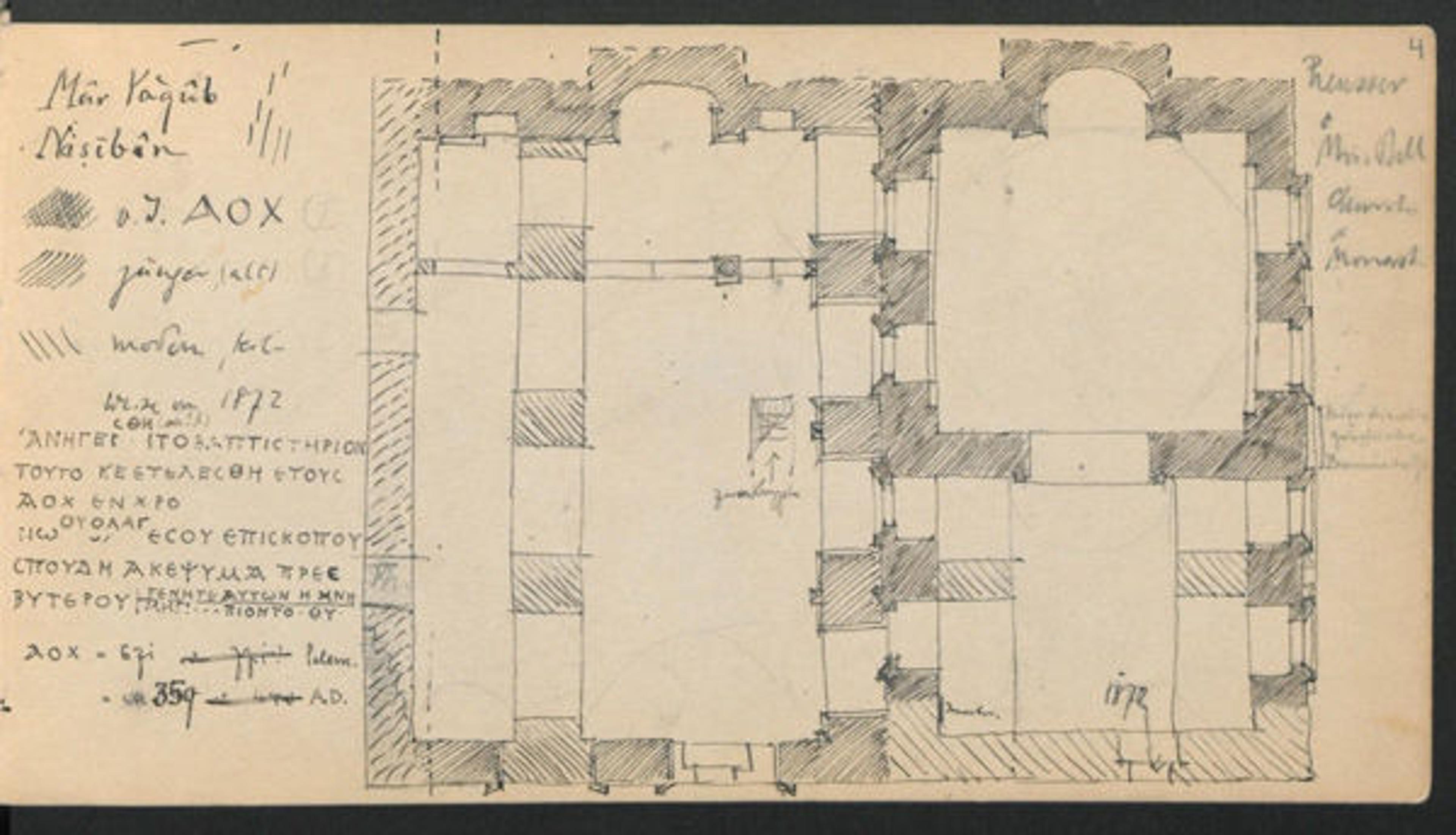

Sketchbook: Turkey and Persia, 1916; page 4. Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

At the beginning of the summer, I worked with a number of Herzfeld's sketches and photographs. While looking through these incredibly interesting materials, I began formatting their records for uniformity and clarity on The Museum System (TMS), which is the Met's online database for every single object in the Museum's collection. After going through almost two hundred items, I was able to export the TMS information to a spreadsheet, and I then began to research Herzfeld's illustrations and photos in order to create subject headings and provide related resources for other scholars.

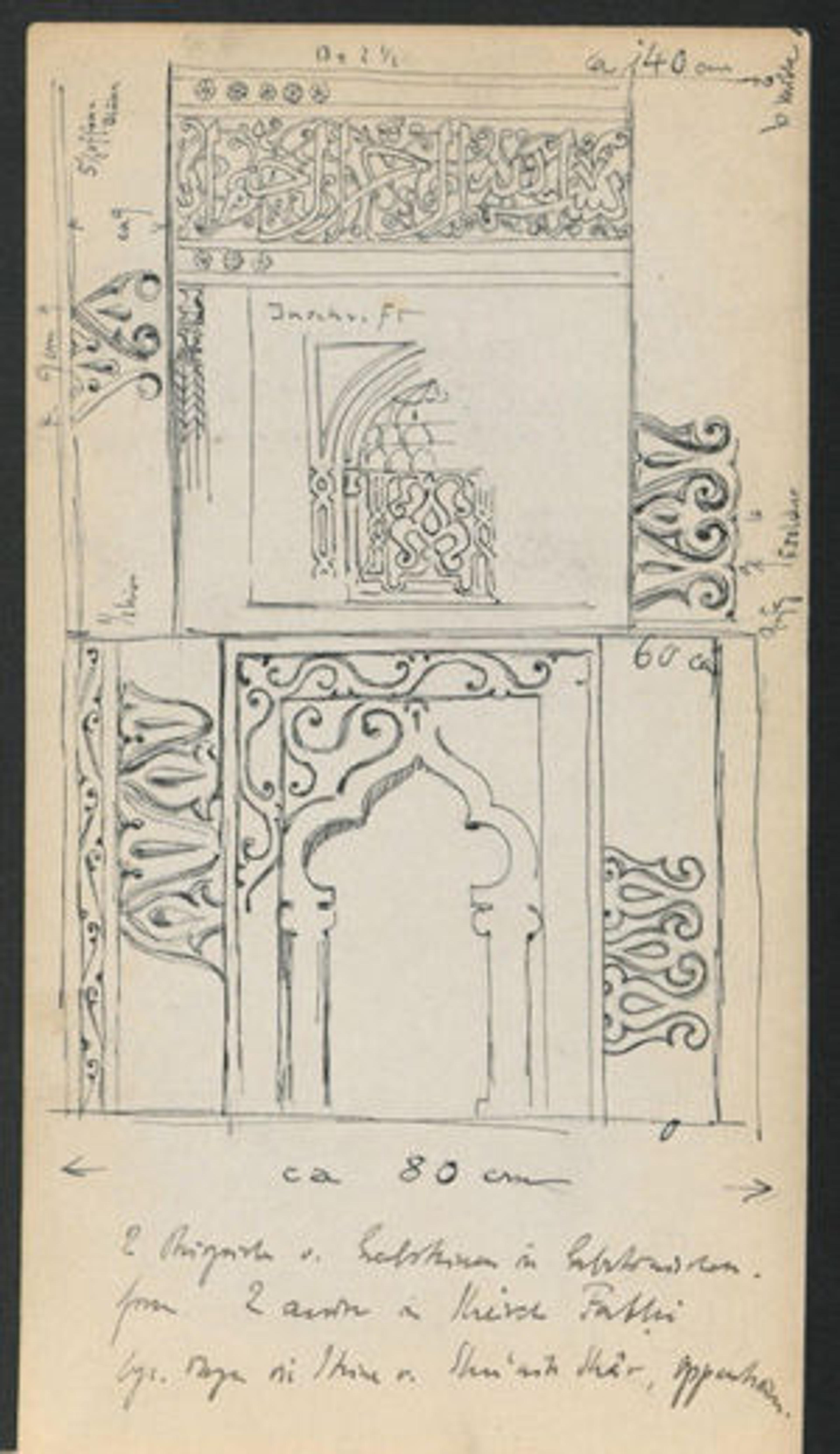

Left: Sketchbook: Turkey and Persia, 1916; page 9. Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

After working with individual sketches and photographs, I moved on to Herzfeld's sketchbooks. These sketchbooks were extremely rewarding to inspect (I went through the same process as I did with the individual sketches and photographs), as they allowed me to gain a better sense of the development of Herzfeld's illustration style and his different types of drawings, which included architectural plans, watercolors, and even maps. I was able to conduct more expanded research with Herzfeld's sketchbooks as well, and I read many resources to determine that he was using azimuths (angular degree measurements) in his panoramic mapping of mountainous regions in Kurdistan.

As I'm reaching the end of my time with these projects, the feeling is bittersweet. I am excited to see the addition of these items from the Herzfeld papers to the digital collection, and I also can't say enough about all of the amazing help and guidance I've received from my supervisor and everyone else in the Department of Islamic Art. I've learned so much more about the museum world this summer than I could have imagined, and this internship has definitely solidified my desire to pursue a career in museums and continue my academic studies in ancient Near Eastern art and archaeology. Thanks to the Met, and to Ernst!

Related Links

In Circulation: "The Ernst Herzfeld Papers at the Met: A Digital Resource Documenting the Study of Near Eastern Civilization" (September 24, 2014)

Teen Blog: "My Life as a College Intern" (August 4, 2015)

Alexandra McKeever

Alexandra S. McKeever is a Museum Seminar (MuSe) intern in the Department of Islamic Art.

Kate Justement

Kate Justement was formerly a Museum Seminar (MuSe) intern in the Department of Islamic Art.