Just Next Door: The Seljuqs and Pergamon Meet at The Met Fifth Avenue

Left: Muhammad ibn Abi'l-Qasim ibn Bakran al-Najjar al-Isfahani al-Salihani. Astrolabe (detail), dated A.H. 496/A.D. 1102–3. Iran, Isfahan. Museo Galileo—Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Florence (1105). Right: Fragmentary colossal head of a youth, 2nd century B.C. Greek, Hellenistic Period. Marble; H. 22 7/8 in. (58 cm). Berlin, Pergamonmuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (AvP VII 283)

«The Met Fifth Avenue is the host of two landmark exhibitions opening this month, Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World and Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. These two exhibitions—each a first in the United States in regard to historical period, theme, and objects displayed—open not only under the same roof, but also next door to each other, with the Pergamon exhibition now open in gallery 899, and Court and Cosmos opening on April 27 in gallery 999. This spatial arrangement of the two exhibitions presents visitors with an opportunity to encounter the artistic splendor of both realms: those who ruled after the death of Alexander the Great in the ancient city of Pergamon (now Bergama, in present-day Turkey); and the Seljuqs, who centuries later came to reign over territories once conquered by the Macedonian hero himself—a leader they venerated as an exemplar.»

The Seljuqs, whose name derives from their eponymous founder, Seljuq, were a nomadic Turkic tribe that sprang out of the Eurasian Steppe to form numerous powerful dynasties. Although we can confirm little about the life of this dynastic founder, we know for certain that, at their peak, the Great Seljuqs and their successor dynasties (the Rum Seljuqs, the Artuqids, and the Zangids), though divided over roughly three centuries of political, military, and cultural dominance between 1038 and 1307, spanned the whole of West Asia—from the eastern reaches of today's Central Asian republics, across Iran, Iraq, and Syria, to Eastern Anatolia in Turkey.

Left: Standing figure with feathered headdress, mid-11th century–mid-12th century. Iran. Islamic. Gypsum plaster; modeled, carved, polychrome-painted, gilded; H. 47 in. (119.4 cm), W. 20 1/2 in. (52.1 cm), D. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Cora Timken Burnett Collection of Persian Miniatures and Other Persian Art Objects, Bequest of Cora Timken Burnett, 1956 (57.51.18). Right: Sirr al-Asrar (Secret of Secrets), 1189–1211. Mosul. Ink, gold, and opaque watercolor on paper; 7 1/2 x 5 in. (19 x 12.7 cm). Kislak Center for Special Collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania Library, Philadelphia (LJS 459)

In their geographic scale, the Great Seljuqs and their successors, particularly the Rum Seljuqs in Anatolia (ca. 1081–1307), rivaled some of history's great imperial dynasties, such as the Byzantines, whom they defeated. The feathered headdress, rich vestment, and arms in the image of the standing figure above (left), who may have been a guard, a vizier, or a sovereign's courtier, conveys awareness of this grand rulership and authority. Scholars believe that this standing figure was part of a wall decoration scheme used in Seljuq palace reception areas, and indeed, it will be among the first objects to receive viewers as they enter the exhibition hall.

Seljuq history and its material culture are immensely rich due in part to their intricately layered cultural memory, which integrates and reworks many antique constructions of the past. The exhibition highlights how interest in Greek literature, medicine, and science was at the heart of court interests, as shown in the series of letters written by Aristotle to his pupil Alexander the Great that make up the manuscript Sirr al-Asrar (Secret of Secrets), on loan to The Met from the University of Pennsylvania. The manuscript, attributed to "the noble king Arslan Shah bin Mas'ud bin Mawdud," as it reads in the frontispiece (above right), was presumably translated from Greek into Arabic. In it, Aristotle advises Alexander on how best to govern and lead.

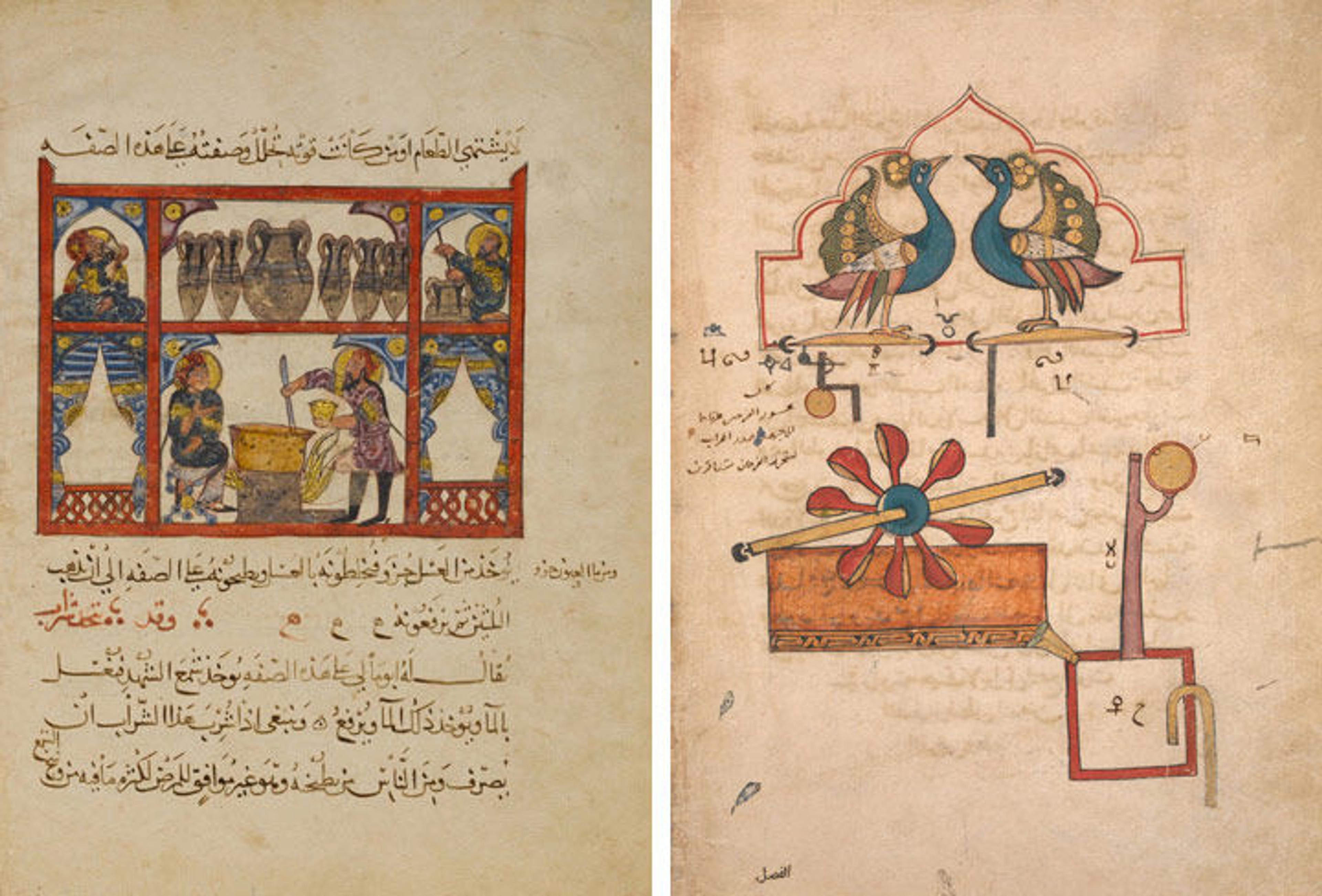

Left: "Preparing Medicine from Honey," folio from a Dispersed Manuscript of an Arabic Translation of the Materia Medica of Dioscorides, A.H. 621/A.D. 1224. Iraq or Northern Jazira, possibly Baghdad. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; H. 12 3/8 in. (31.4 cm), W. 9 in. (22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Cora Timken Burnett, 1956 (57.51.21). Right: Badi al-Zaman ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari (1136–1206). "Design for the Water Clock of the Peacocks," folio from a Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices by al-Jazari, dated A.H. 715/A.D. 1315. Syria. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; 12 3/8 x 8 5/8 in. (31.4 x 22.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1955 (55.121.15)

First translated in ninth-century Baghdad, the Greek physician Dioscorides's De Materia Medica, written in the first century B.C., was widespread not only in the Seljuq regions but in medieval Islamic intellectual realms. In Court and Cosmos, visitors will encounter a physician making medicine from a mixture of honey and water to cure physical weakness and poor appetite (above left). In the exhibition, he is paired with another doctor, visiting us from the Walters Art Museum, who prepares a medicinal cure for digestive problems.

Interest in medicine was parallel to that of astronomy and technology during the Seljuq Period. On display will be a folio showing a design for a water clock of the peacocks (above right) from the well-known treatise by Al-Jazari, who served in the Artuqid court in Diyar Bakr, on practical and mechanical devises, Kitab fi Ma'rifat al-Hiyal al-Handasiyya (Book of the Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices). The Al Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyya Kuwait, is sending our way a second folio with a design for the Automata of the Slave Girl Serving a Glass of Wine, which shouldn't be missed!

Left: Ewer, ca. 1180–1210. Iran, Khurasan. Islamic. Brass; raised, repoussé, inlaid with silver and black compound; H. 15 3/4 in. (40 cm), Diam. 7 1/2 in. (19.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1944 (44.15). Right: Detail view of human-headed (anthropomorphic) inscriptions as well as dragons and lions.

As a curatorial fellow who was fortunate enough to participate in the Department of Islamic Art's planning of this exhibition, what piqued my curiosity most was not how Seljuq sultans adopted the names of ancient Iranian kings to show their desire to connect to ancient Iranian history in addition to their interest in Greco-Roman and Byzantine heritage, but rather the appearance—characteristic of the period—of anthropomorphic inscriptions on metalwork, as in the ewer above. Objects such as this, which featured benedictory inscriptions and sometimes poetry, circulated widely throughout Seljuq domains.

These inscriptions are often accompanied by courtly scenes, animals such as lions and dragons, as well as astrological and zodiac imagery. The human-headed letters unify image and script (above right, detail view), giving the illusion that the object is speaking to the beholder. Through experiences with objects like this Khursani ewer, I came to see how in The Great Age of the Seljuqs, Court and Cosmos often converged as one.

I encourage you to embark on your own Seljuq adventure, and to experience it by way of the Pergamon!

Related Links

Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World, on view April 18–July 17, 2016

Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, on view April 27–July 24, 2016

Alzahraa Ahmed

Alzahraa K. Ahmed is the 2015–17 Hagop Kevorkian Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Islamic Art.