Of Calligraphic Lines and Radiant Light: Nasreen Mohamedi and Islamic Aesthetics

Installation view of Nasreen Mohamedi, on view at The Met Breuer through June 5, 2016

"Is not the chiasma of light and line(s) the quintessence of Mohamedi's art?"

—Deepak Ananth, "The Imagination of the Line"

«One of the inaugural exhibitions at The Met Breuer is a retrospective of Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi (1937–1990). Organized by the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, the exhibition spans Mohamedi's entire career, bringing together works on paper, photographs, and little-seen diaries. Walking through a tightly directed path created through the parallel placement of long temporary walls, viewers can follow the chronological unfolding of the artist's oeuvre—even as most of her works remain untitled, unsigned, and undated!»

At a time when many of her contemporaries in India were working with figuration and color, Mohamedi worked in a largely monochromatic abstract mode and developed a rigorous practice that explored the possibilities of line on paper. Her carefully drawn strokes describe spaces and forms on square or rectangular sheets of paper that require the visitor to draw near and look closely at the fine details to fully understand their conceptual complexity and visual subtlety.

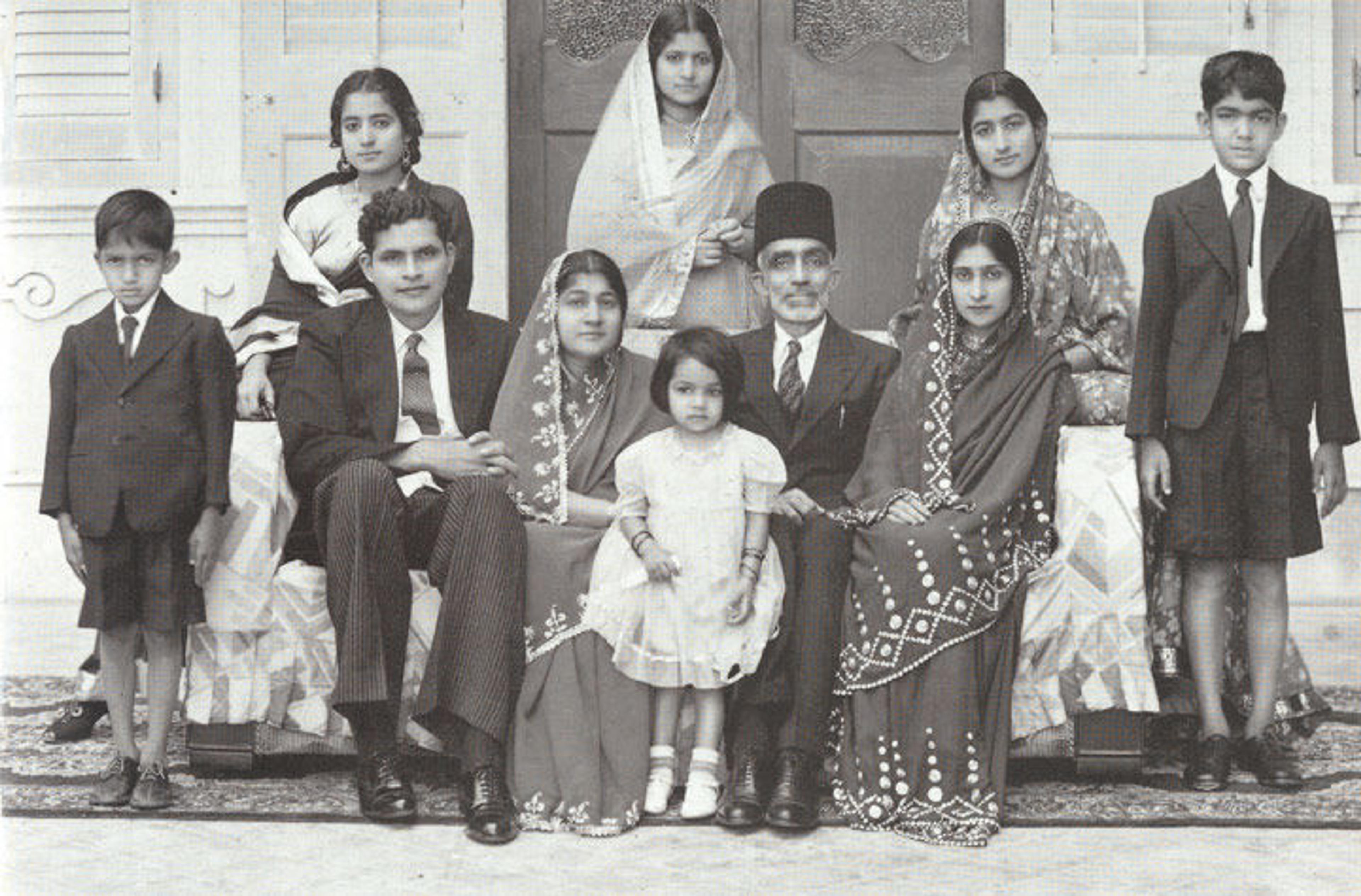

Born in 1937 into an elite family from the Tyabji clan (Shias from the community of Sulaimani Bohras) in Karachi (British India, now in Pakistan), Mohamedi's family moved to Bombay (now known as Mumbai) in 1944, where she spent the rest of her childhood.

Back row, left to right: Camar, Saleha, and Rukaya (sisters). Front row, left to right: Anwar (brother), Akhtar (brother-in-law), Zainab (mother), Ashraf (father), Vazir (sister), and Shams (brother), with Nasreen in the center, aged four. Photographed in Karachi (British India, now Pakistan), ca. 1941. (Source: Nasreen in Retrospect)

In a part of the world often overdetermined by a religious affiliation that has a disturbing tendency to spill into the political and public realm, it is worth noting that while Mohamedi was not an agnostic, it would be equally limiting to describe her simply as a Muslim artist. Choosing to live in India, Mohamedi was invested in a secular modernity and ethics, and as such her faith—in whatever form it took—was intensely personal, and not a prescriptive reference for her public practice.

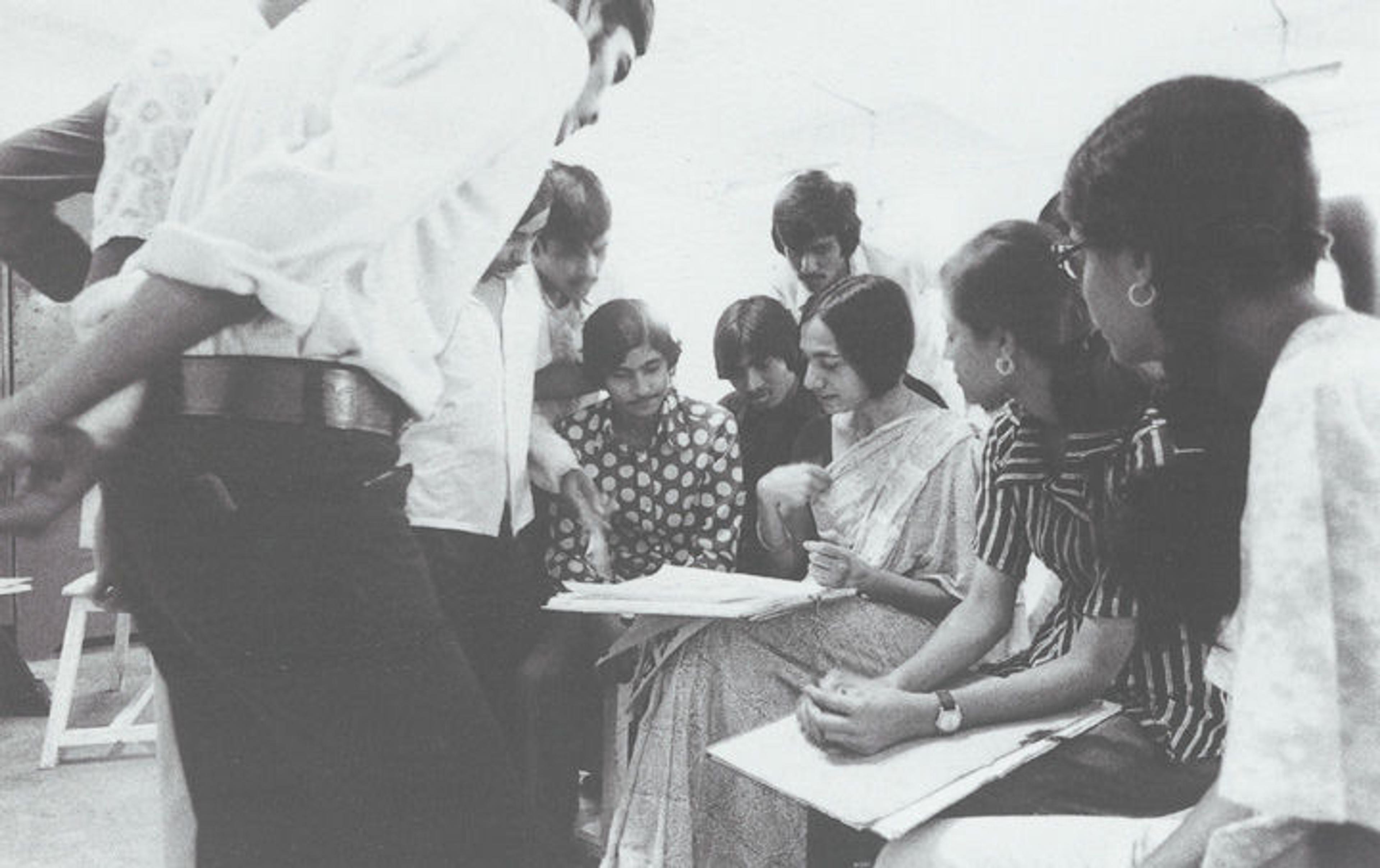

Mohamedi with students at the Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University, Baroda, 1970s. Photo by Jyoti Bhatt. (Source: Contemporary Art in Baroda)

Mohamedi drew upon early 20th-century Western abstraction just as easily as the nonobjective mode of painting espoused by her friend and older contemporary V.S. Gaitonde (1924–2001). Yet considered in the context of her travels across the Middle East, West Asia, and South Asia, her work can perhaps also be read as having a shared sensibility with an Islamic aesthetics of abstraction as seen in calligraphy, geometry, poetry, and in the imagery of light.

The Met Breuer is an exhibition space in which art from the 20th and 21st centuries is situated within the continuum of 5,000 years of global visual cultural production represented in The Met collection. To thus consider modern and contemporary art alongside historic collections is a rare opportunity to make connections and find resonances across temporal and geographic boundaries. Having walked the galleries of the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia on multiple occasions since they reopened in 2011, and then having worked on Nasreen Mohamedi, I was struck by some of the shared sensibilities noted above. Fortunately there are several works in the collection of the Department of Islamic Art that allowed me to make certain connections with Mohamedi's work, some formal and some poetic.

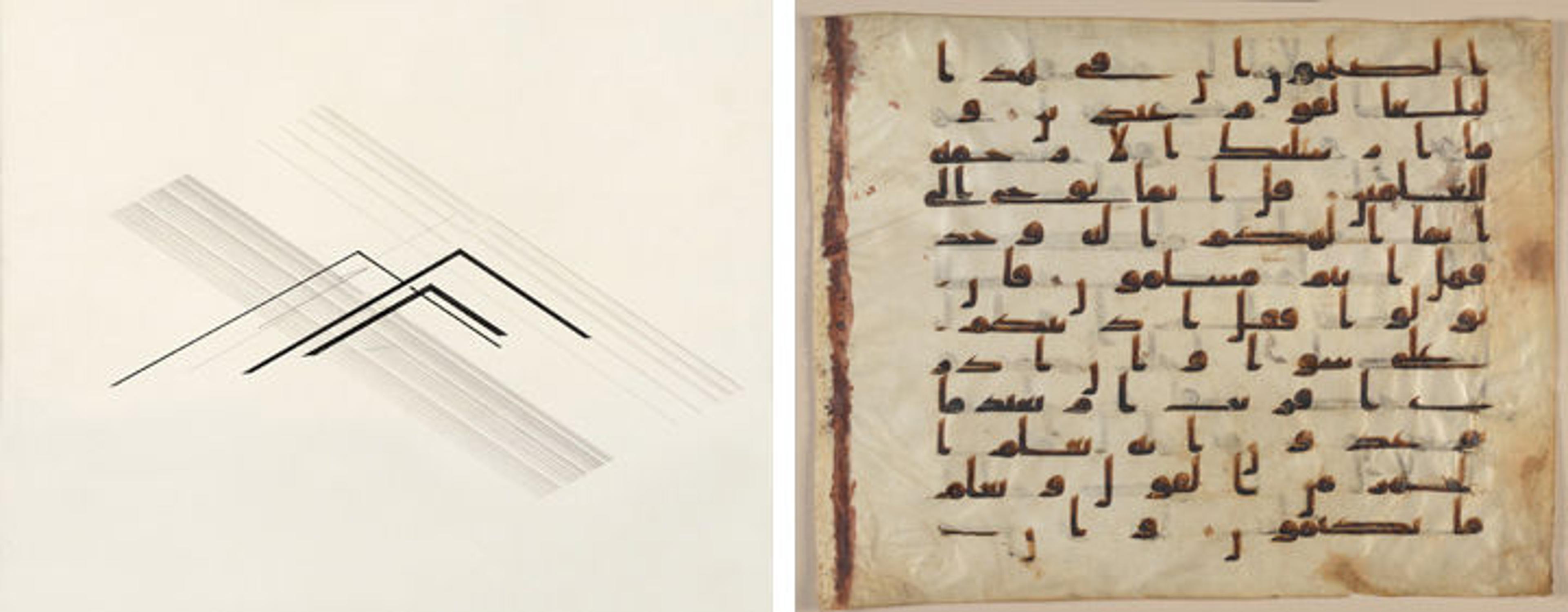

Calligraphy

Scholars have described Mohamedi's working method as that of a scribe, and certainly the manner in which she deployed her line invokes a calligraphic form of inscription. At times the modulation of ink flows is more reminiscent of East Asian calligraphy, but her contours and her ultimate preference for angular forms suggests a sympathy with Islamic calligraphy. In fact, she is known to have been drawn to the Kufic script, and perhaps there is a resonance in the Mohamedi's chevrons, a recurring element in her work.

Left: Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937–1990). Untitled, ca. 1980, Ink and graphite on paper. Private collection, Courtesy Talwar Gallery. Right: Folio from the "Tashkent Qur'an," late 8th–early 9th century. Syria, Yemen, or North Africa. Islamic. Ink on parchment; 21 5/8 x 27 9/16 in. (55 x 70 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 2004 (2004.87)

Mohamedi suffered from degenerative neuromuscular Huntington's disease, but nevertheless pursued an exacting practice that required careful, deliberate, and disciplined application of line on paper. I can imagine the elegant black letters describing the Arabic proverb "Planning before work protects you from regret" from a milky white 10th-century bowl from Nishapur, Iran, as appealing to the artist in both form and sentiment.

Geometry and Light

During her travels and from notes in her diaries, it is evident that Mohamedi clearly admired the elegance of Islamic architecture. She was drawn to the geometry of patterns, the creation of expansive spaces, and the manner in which built forms could animate one's perception of light. The sacredness of light is, of course, key in an Islamic context—a well-known verse from chapter 24 of the Qur'an, "Surat al-Nur" (The Light), begins with: "God is the light of the heavens and the earth. The semblance of His light us that of a niche in which is a lamp."—but for Mohamedi, a keen awareness of the possibilities of light became a guiding artistic principle. It would be too simplistic to read her interest in light as a mystical one alone, even though her many observations on the subject often bear striking similarity to metaphors of light used by the poets she loved including Rumi and Ghalib.

Left: Mosque lamp of Amir Qawsun (inscribed with the "Light" verse of the Qur'an), ca. 1329–35. Egypt. Islamic. Glass, colorless with brown tinge; blown, blown applied foot, enameled and gilded; H. 14 1/8 in. (35.9 cm), Max. diam. 10 1/16 in. (25.6 cm), Diam. with handles 10 5/16 in. (26.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.991)

For instance, in 1968 Mohamedi notes in her diaries, "Grains of sand which sparkle with the sun." Yet clearly, given her interests in photography and the physics of light, she had a much more complex relationship to the subject. While on the one hand her relationship to light was an abstract, even spiritual one, she was also fascinated with its physical properties.

In her photographs taken at the 16th-century Mughal city of Fatehpur Sikri, for instance, she is less interested in the arched gateways and domed buildings, but rather trains her camera on the shadow cast by an empty water channel on a sandstone terrace.

Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937–1990). Untitled, ca. 1972. Gelatin silver print. Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

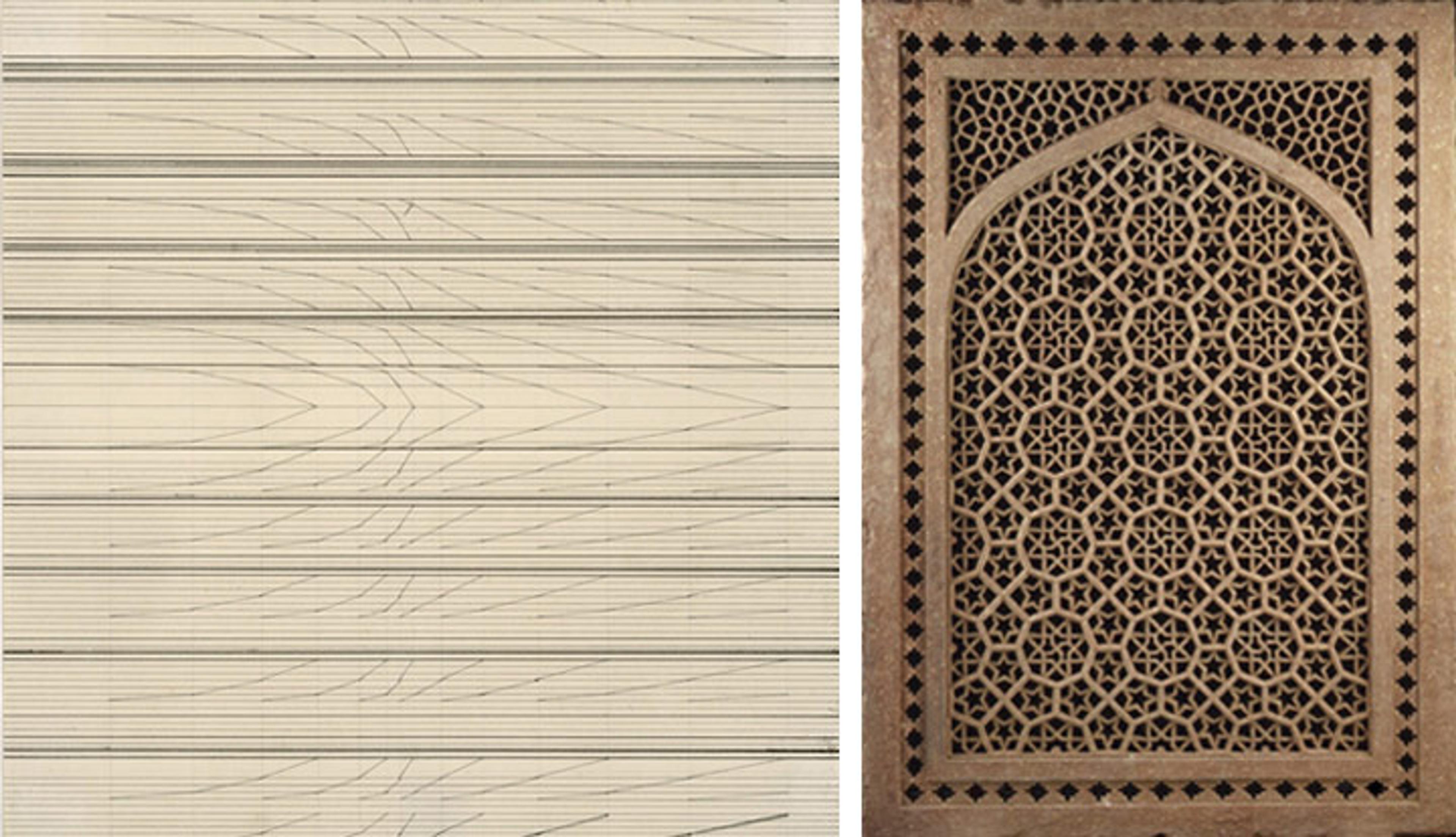

She was also keenly aware of how line and form could intercept the path of light. For her, the plain sheet of white paper was a space suffused with light upon which she wielded intersecting lines that could describe rays and beams or create surfaces that shimmer. In this regard, her latticed lines work much in a similar manner to the exquisite perforated stone screens or jalis so often seen on South Asian Mughal monuments.

Left: Nasreen Mohamedi (Indian, 1937–1990). Untitled, ca. 1970. Ink and graphite on paper. Private collection. Right: Pierced window screen, second half 16th century. India. Islamic. Red sandstone; pierced, carved; H. 73 in. (185.4 cm), W. 51 5/16 in. (130.3 cm), Th. 3 1/4 in. (8.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1993 (1993.67.2)

In The Met Breuer exhibition, Mohamedi's works on white sheets of paper (some of which have yellowed with age) still seem luminous against the subtly tinted grey walls of the galleries. Never having been part of any group or movement, and having steadfastly charted her own aesthetic course, Mohamedi's work has largely evaded domestication into "canons" of art. In considering her work alongside objects of Islamic art I am not attempting to locate her practice in a historic lineage, but rather in bringing these works into the same orbit, I am suggesting the possibilities for both the reflection and refraction of certain formal concerns and conceptual approaches in Mohamedi's art.

Resources

Karode, Roobina, Geeta Kapur, Deepak Ananth, and Andrea Giunta. Nasreen Mohamedi: Waiting Is a Part of Intense Living. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2015.

Sheikh, Gulammohammed, and Belinder Dhanoa. Contemporary Art in Baroda. New Delhi: Tulika, 1997.

Altaf, ed. Nasreen in Retrospect. Bombay: Ashraf Mohamedi Trust, 1995.

Related Event

MetFridays—The Maximum Out of the Minimum: Reconsidering Nasreen Mohamedi

Friday, June 3, 2016, 6–7 pm

The Met Fifth Avenue - Bonnie J. Sacerdote Lecture Hall, Uris Center for Education

Brinda Kumar

Brinda Kumar is an assistant curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art.