Patterns of the Past: Medieval Islamic Textiles in the 20th Century

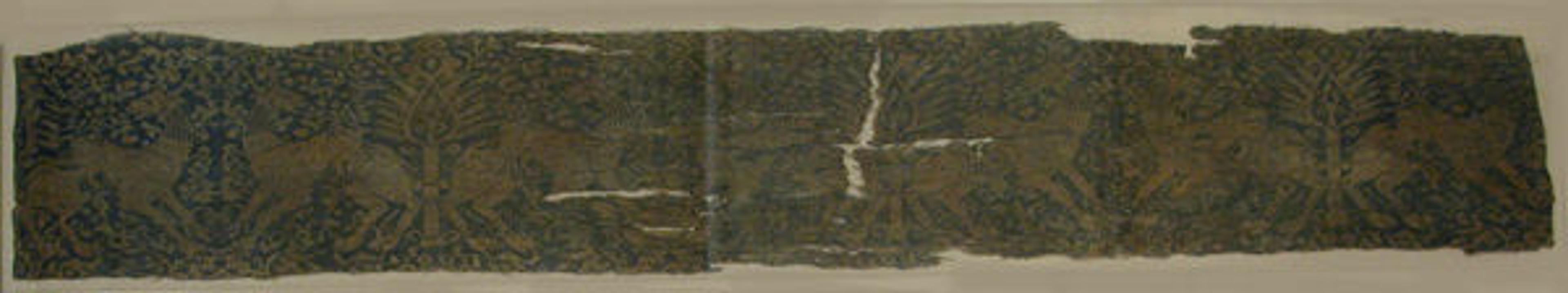

Fragment, 20th century. Iran. Islamic. Silk; H. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm), W. 21 5/8 in. (54.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1959 (59.134)

«Transformed: Medieval Syrian and Iranian Art in the Early 20th Century, a fascinating new exhibition curated by Martina Rugiadi, explores the complexity of medieval Syrian and Iranian decorative arts, including ceramics, glass, and textiles. The exhibition engages the 20th-century history of the conservation and revision of these objects, revealing approaches ranging from invasive over-painting to outright reproductions and forgeries. As someone who researches textiles, I have a particular investment in exhibitions like this one, which trace the changing fortunes of my favorite medium. Moreover, as a fellow in the Department of Islamic Art this year, I have been struck by the way that many textiles in the Met's collection reveal the dual histories of early Islamic art and the collecting practices of the 20th century.»

In many ways, textiles were the star medium of early 20th-century histories of Islamic art, because they illuminated previously unknown modes of design, routes of circulation, and innovations in technology. In the aftermath of World War I, large-scale official (and unsanctioned) excavations began to take place in Iran and Syria. Between 1924 and 1925 in the northern Iranian city of Rayy, archaeologists began to uncover fragments of early textiles from the 11th and 12th centuries within a series of tombs near the Bibi Shahr Banu shrine. Soon, small textile fragments from Rayy were selling for thousands of dollars to museums and private collectors in the United States and Europe, many of which are now held by the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum. With such high valuations for these textiles and the lack of knowledge about the cloth of this early period, the situation was ripe for exploitation and forgeries immediately followed, exemplified by two of the Met's textiles on view in Transformed (59.134 and 30.67).

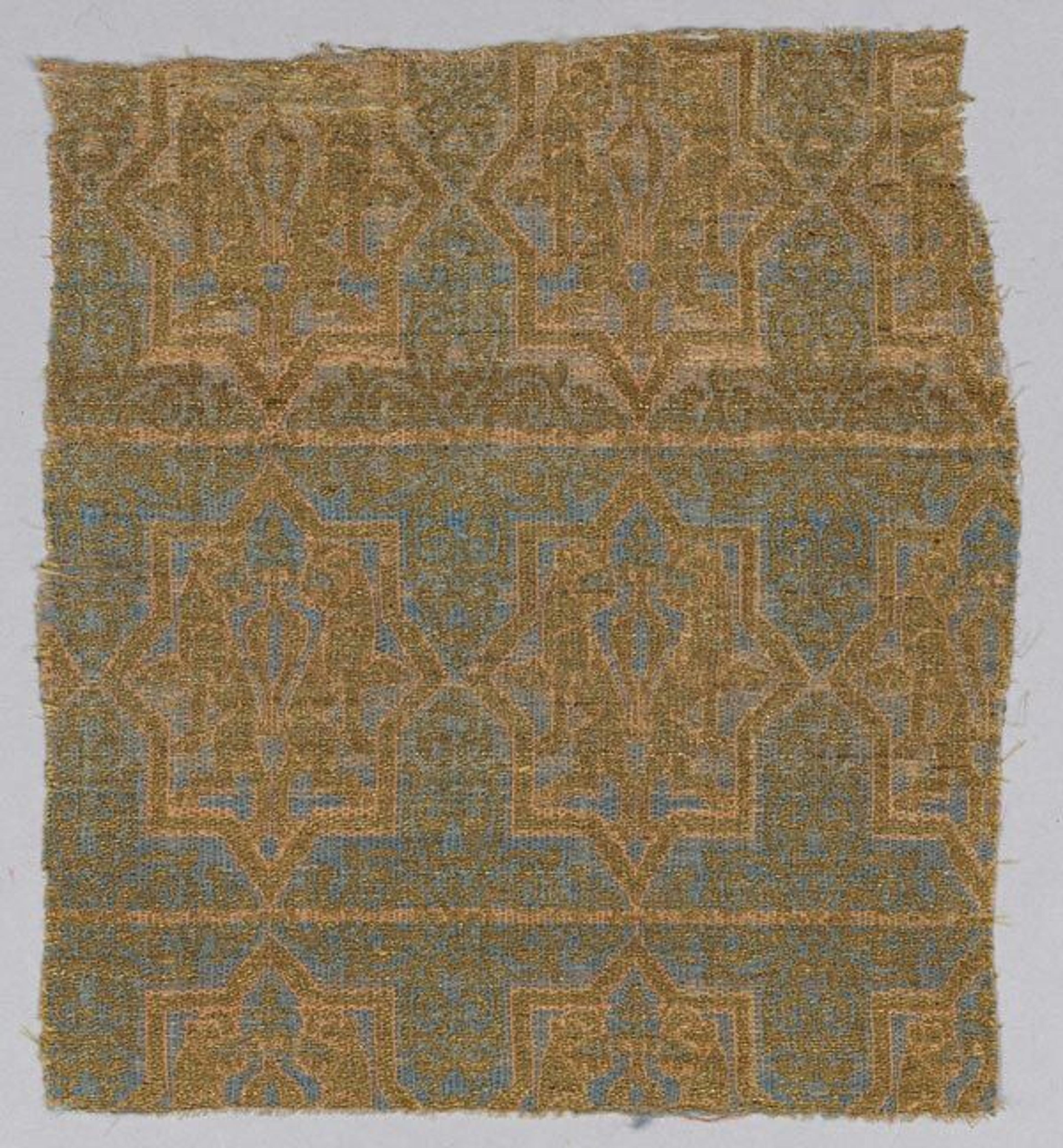

Textile with pattern of birds and stars, 11th–12th century. Iran. Islamic. Silk; samite; Textile: H. 5 in. (12.7 cm), W. 5 1/4 in. (13.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1946 (46.156.11a)

The third textile, a fragment from Seljuk Iran, is believed to be genuine and bears an intriguing genealogy. It came from the fine-arts dealer and connoisseur Giorgio Sangiorgi, who operated the Galleria Sangiorgi in Rome. When I saw that the textile had passed through his hands, I was reminded that I had seen Sangiorgi's name in the initial report on a set of Islamic textiles found in a tomb in Verona, Italy. Sangiorgi is the thread connecting two of the early 20th-century's most sensational stories of Islamic textiles. At the same time that excavators were discovering early Iranian textiles in Rayy's crumbling tombs, Italian officials were finding Islamic textiles in their own backyard.

In 1921, city officials in Verona sanctioned the opening of the tomb of the widely feared and yet deeply beloved Cangrande della Scala, a patron of Dante Alighieri. Cangrande had died in 1329, but the occasion of the opening of the tomb was the sixth centenary anniversary of the death of Dante. Inside the tomb, guarded by a smiling equestrian statue of Cangrande, the officials found not just a body that had naturally mummified, but also a store chest of late 13th-century and early 14th-century silk textiles whose style, materials, and even large naskhi inscriptions suggested that they must have come from the Islamic lands of Central Asia during the reign of the Ilkhanids. The somewhat careless sewing job on the cape, tunic, and booties suggested that they had been constructed hastily, as Cangrande died of poisoning during a military campaign in Treviso and was quickly brought home and buried.

Giorgio Sangiorgi published the first account of these textiles in 1922, detailing, among other finds, a large-scale fragment with an Arabic inscription of praise for a ruler; a charming lampas silk with a pattern of leaping rabbits, fish, and birds; fragments of a blue-and-gold tunic with woven images of swans and lions; and a red silk cloak made of Chinese-inspired silk brocaded with lotus flowers and vegetal scrolls. Recent scholarship has shown that textiles from the Middle East and Mongol-dominated Central Asia began appearing in European inventories as panni tartarici, or "Tartar cloth," by the middle of the 13th century, reaching Europe via the Byzantine Empire and the Mediterranean Sea trade.

The Verona tomb was not the only European repository of early Islamic textiles. Throughout the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, various medieval tombs in present-day Austria, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Italy, and France were found to contain Near Eastern, Central Asian, and Iranian textiles. Some of the earliest textiles were brought back from the Crusades; others, like the Verona fragments, were purchased by European merchants in the lively trading city of Tabriz, the capital of the Ilkhanids.

These precious cloths were used to safeguard Christian relics in cathedral treasuries and to clothe the bodies of emperors and princes when they were laid to rest. Because they appeared in church inventories or were sealed until exhumation, these textiles bore an impeccable provenance. As a result, Islamic textiles in European treasuries often became the standard against which discoveries from Central Asia, Iran, Syria, Iraq, and Egypt were judged to be authentic or fake. The Iranian textile in Transformed, for instance, might be further authenticated by a textile in the Met's collection that was made in Almeria in Spain in the 13th century and preserved as part of the vestments of San Valero.

Textile fragment from the chasuble of San Valerius, 13th century. Spain. Islamic. Silk, gilt animal substrate around a silk core; taqueté; Textile: L. 6 in. (15.2 cm), W. 5 1/4 in. (13.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1946 (46.156.3)

Giorgio Sangiorgi was also the dealer responsible for this textile. With its eight-pointed stars and blue color scheme, it resembles in motif and style the much more intricate Iranian textile that appears in the exhibition. This textile exhibits another layer of cross-cultural contact, as it is believed that such medieval Spanish textiles were made by Muslim weavers inspired by imported textiles from the wider Islamic world. The case could plausibly be made, therefore, that this Spanish textile, with its secure dating, can help to authenticate the Iranian textile by virtue of being a copy that came after it.

In good faith, textile historians in the early 20th century used similar arguments to smooth over irregularities in textile history—it is what art historians do. One scholar, in an attempt to explain anomalous textiles that were later determined to be forgeries, argued that the strange textiles had been a necessary bridge between an earlier and a later style.

Yet I am always reminded that the tomb of Cangrande della Scala might best be seen not solely as an authenticating mechanism, but as a cautionary tale. It contains a totally eclectic combination of textiles which, beyond technical and material similarities, bear little stylistic relationship to one another. The past, Cangrande seems to proclaim with his enigmatic smile, is messy, illogical, and visually diverse. While we as art historians and museum curators are always seeking a way to tie one object to another, it is sometimes helpful to remember that the most authentic sites are preserved by accident and were formulated by contingency. Our art-historical inheritance might best be imagined as a hastily constructed gown that happened to endure for millennia.

References

Mackie, Louise. Symbols of Power: Luxury Textiles from Islamic Lands, 7th–21st Century. Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 2015.

Sangiorgi, Giorgio. "Le stoffe e le vesti tombali di Cangrande I della Scala." In Bollettino d'Arte del Ministero della P.I. XV (1922): 443–457.

Wardwell, Anne E. "Panni tartarici: Eastern Islamic Silks woven with Gold and Silver (13th and 14th centuries)." In Islamic Art 3 (1988–1989): 95–173.

The author wishes to thank Vera-Simone Schulz for their conversation about the textiles from the tomb of Cangrande della Scala.

Sylvia Houghteling

Sylvia Houghteling is the 2015–16 Sylvan C. Coleman and Pamela Coleman Memorial Fund Fellow in the Department of Islamic Art.