Beasts and Hunters in the Galleries: Mesmerizing Ivories and Their Making

Ivories on display in gallery 457. Photo by Silvia Armando

«Every time I walk through gallery 457 I am arrested by a big vitrine displaying a rich range of medieval ivory objects produced around the shores of the Mediterranean. This collection of ivories holds secret stories of transformation, from secular to sacred, ending ultimately in their place as objects of desire for collectors. Rare and durable, elephant ivory was valued as one of the most precious materials in medieval times, and a wide range of artifacts were created by skillful craftsmen throughout the Mediterranean. The main patrons were powerful rulers such as Muslim caliphs, Latin or Byzantine emperors, and high-ranking ecclesiastics and noblemen, who took advantage of the ivory supply being imported from Africa.»

Of a shimmering but warm white tint, fine-grained but smooth to touch, ivory offered an extraordinary sensory experience that was sometimes metaphorically associated with a woman's beauty and her skin, such as the exquisitely carved tenth-century ivory casket on loan from the Hispanic Society of America (L.2011.46.7), which carries an inscription that compares it to "the firm breast of a delicate maiden." Many of these objects circulated widely, were passed from one owner to another, and often ended up in church treasuries. Here their original purposes were reinvented, and they were often turned into reliquaries.

I was lucky enough to have this vitrine case opened for me, and to hold some of these amazing objects in my hands. A close look can tell much about the cutting and decoration techniques, revealing the incredibly varied ways in which an elephant tusk could be worked and shaped.

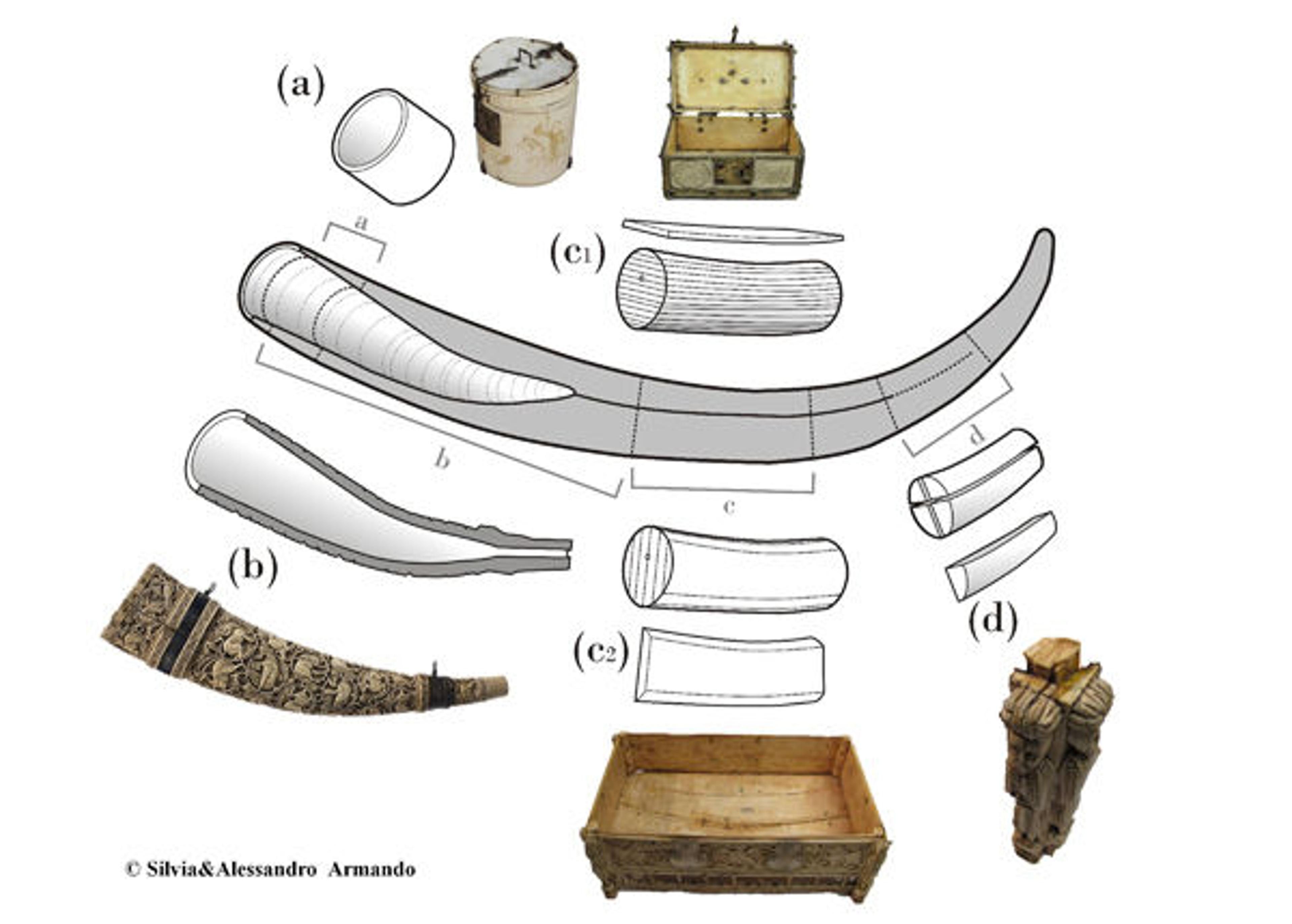

Diagram of an elephant tusk showing sections of possible cuts and the different objects which could be created from them. © Silvia and Alessandro Armando

The tusk of an African elephant can reach up to three meters in length and almost twenty centimeters in diameter at the proximal end, closer to the jaw. Here the tusk has a hollow, known as the pulp cavity, which becomes gradually narrower. Only a minuscule canal runs up to the tip, or distal end.

In the vitrine, a magnificent ivory horn shows the natural bending of the tusk. It was carved around the pulp cavity (area B in the diagram above), a process which becomes clearer when looking at the fragment of a very similar artifact in the same case.

Left: Horn (Oliphant), 11th–12th century. South Italian. Ivory, silver, leather; 23 1/16 x 4 15/16 x 4 in. (58.6 x 12.5 x 10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1904 (04.3.177a). Right: Fragment of an oliphant, 11th–12th century. Italy, Sicily. Norman Italy. Ivory; carved; L. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm), W. 4 1/8 (10.5 cm), D. 3 9/16 in. (9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.219)

These horns were known as oliphants, a name clearly derived from "elephant," and made famous by Charlemagne's paladin Roland, who played his olifan just before dying in battle at Roncevaux in A.D. 778. When properly blown, oliphants emit daunting but intriguing sounds. They were likely carried during hunts and military combats, but it is possible that these preciously carved pieces were also used in ceremonies as symbols of power and prowess.

Their surface is filled with roundels carved in bas-relief, enclosing exotic and fantastic creatures: gazelles and peacocks, but also griffins and lions, the wings and the termination of tails of which can turn into the heads of dogs, birds, and hares. My favorite ones are the head of a giraffe peeping out from the lower edge of the broken oliphant and a bird holding in his beak a fish, which is almost his size. Elsewhere on the oliphant, there is also a man holding a sword and a shield. He is remarkably similar to the eight bearded and turbaned figures carved on the corners of a massive casket displayed in the same vitrine. With their severe look, they must have once guarded the precious content of the casket. The casket is populated by creatures like those on the oliphants, and also features two hunters and a woman carried on a palanquin on back of a dromedary.

Details of a man holding a sword and shield and a bird holding a fish, from the fragment of an oliphant. Photos by Silvia Armando

Morgan casket (two detail views), 11th–12th century. Southern Italy. Norman Italy. Ivory; carved; Overall: H. 8 7/8 in. (22.3 cm), W. 15 3/16 in. (38.6 cm), D. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.241). Photos by Silvia Armando

I had the privilege to open this box: it is made of thick plaques, obtained by sawing longitudinal sections from the full part of a tusk (section C2 in the diagram above), which could have well been the same tusk used for one of the oliphants.

Left: Morgan casket (interior). Right: Detail of a single-ivory-bloc angular post on the casket. Photos by Silvia Armando

The carved plaques were fitted to the angular posts previously created by splitting into four the narrower, distal part of the tusk. Each post and its two turbaned figures are obtained from a single ivory bloc (area D), thus proving the technical and artistic mastery of the craftsmen together with the overall delicacy of the carving. These caskets are extremely rare today, so it's certainly worth it to step into gallery 304 in the Department of Medieval Art to find a precious parallel in a unique pen box decorated with virtually identical animals carved from two halves of a narrow but long section of a tusk.

A marvelous dialogue of imageries occurs among these objects: hunters and guards, predators and preys attest to an entire tradition of fantastic and exotic subjects often associated with the pleasures of the princely life.

This discourse expands to artifacts created in different media or decorated with different techniques. A small carved ebony panel on display in the vitrine, featuring a bird of prey and a gazelle against a vegetal background, suggests that iconographic and technical comparisons can be found in Egyptian wood carving of the Fatimid period.

Left: Panel, 10th–12th century. Egypt. Islamic. Wood (ebony); carved; H. 13.7 cm, W. 7cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1933 (33.157.3)

Comparable repertoires decorate the surfaces of other ivory caskets once painted with vivid colors that are now, unfortunately, faded. Close observation of a cylindrical box reveals the presence of gazelles, peacocks, and falconers on horseback wearing precious garments, all evoking the hunting leisure. A rectangular casket features animals enclosed in circular medallions flanked by little birds, echoing those seen on the carved artifacts.

In these examples the elephant tusk was exploited in different ways: the cylindrical box is a cross-section cut near the pulp cavity (area A), while the rectangular one was created assembling together incredibly thin plaques cut longitudinally (area C1).

Left: Box with equestrian falconers (detail), 13th century. Made in Sicily, Italy. Ivory with copper alloy mounts, polychromy; Overall (with mounts): 5 5/16 x 4 5/8 x 5 1/16 in. (13.5 x 11.7 x 12.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1955 (55.29.2). Right: Casket with painted roundels (detail), late 12th–early 13th century. Italy, Sicily. Norman Italy. Ivory, painted; gilded silver mounts with glass, quartz, and turquoise inlays; Overall: H. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm), W. 7 1/8 in. (18.1 cm), D. 4 3/8 in. (11.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Alastair Bradley Martin, 1973 (1973.90). Photos by Silvia Armando

The best way to appreciate these refined artworks is, of course, to visit the Museum; you could observe them for hours and keep on discovering new technical and ornamental details. And I will tell you one last secret: a little elephant is hidden among the infinite decorative variations. Everyone is invited to the Met to look for it!

Related Link

Read more about the use of ivory during medieval times on the Game of Kings blog, which accompanied the exhibition The Game of Kings: Medieval Ivory Chessmen from the Isle of Lewis, on view at The Cloisters November 15, 2011–April 22, 2012.

Silvia Armando

Silvia Armando was the 2014–2015 Hanns Swarzenski and Brigitte Horney Swarzenski Fellow in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.