Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown's Collection Celebrates 125 Years at the Met

Anders Zorn (Swedish, 1860–1920). Mrs. John Crosby Brown (Mary Elizabeth Adams, 1842–1918), ca. 1900. Oil on canvas; 29 x 23 3/4 in. (73.7 x 60.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Eliza Coe Moore, 1959 (60.85)

February 16, 1889

To the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum, New York

Gentlemen,

I hereby present to the Museum, if you deem it worthy of acceptance, my collection of musical instruments. It numbers at present about 270 instruments [chiefly those of distant peoples], with a few interesting European specimens. . . . The instruments have all been carefully catalogued, and accurate pen and ink drawings, descriptions, and measurements have been prepared . . .

I hope to continue my work and to add to it from time to time . . . the collection is of value as a whole, as illustrating the habits and tastes of different peoples. It will become more valuable every year, as many of the instruments . . . now in the collection are rapidly disappearing and even now some of them cannot be replaced. I remain, Gentlemen, with high esteem,

Yours sincerely,

Mary E. Brown

«With her letter of February 16, 1889, Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown (1842–1918) became a "surprise collector" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. As a woman of the time, her confident, independent tone was as unexpected as her collection was little known. She was the wife of a respected New York merchant banker, John Crosby Brown of Brown Bros. & Co., and she herself was of impeccable New England ancestry—the grand-daughter of shipbuilders, clergymen, and schoolmen.»

The Brown family, though familiar to several Met trustees, had no prior connection to the Museum, and Mrs. Brown's sudden appearance and unconventional proposed donation were not the last surprises that she would give the Metropolitan. Her initial gift of 270, mostly non-European, instruments (variously described by different sources as 276 or 278) was accepted at a fully attended meeting of the trustees in Cornelius Vanderbilt's Grand Central Station office on February 18, 1889. It had been inspected some weeks earlier by a committee from the Museum, "who were convinced that the collection would be an interesting and valuable acquisition to the Metropolitan Museum's art objects." The New York Times described it as a "rare assortment" of instruments "unsurpassed in rarity or completeness by the collections in Paris, Berlin and Vienna," and only rivaled by the one in London, England, at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum).

One of the first instruments donated by Mary Elizabeth Brown. Yunluo ("Cloud Gong"). Qing dynasty (1644–1911), 19th century, China. Bronze; Frame Height: 28 in. (71.1 cm); Width: 16 1/2 in.; Diam. of largest gong: 4 in. (10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.15 a)

Mrs. Brown had one additional surprise, which would only reveal itself in the ensuing years: Though she donated her collection irrevocably to the Museum, Mrs. Brown requested that during both her lifetime and that of her eldest son, William Adams Brown, who was associated in her work, they be allowed "access to the instruments . . . and also the privilege to improve the collection by substituting superior for inferior instruments of the same kind." This caveat, casually approved by the Museum's trustees, effectively installed Mrs. Brown as the curator of her own collection and enabled her to add to it at will.

By her death in 1918, the "Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments of All Nations" (named in honor of Mrs. Brown's husband) contained approximately 3,600 instruments and unnumbered supporting materials, including working models of pianos and over 700 portraits of musicians. As no one else in America was broadly knowledgeable in the field, she became the Museum's and the country's self-taught and fully acknowledged expert on musical instruments worldwide. By 1901 her collection occupied five rooms at the Met, and the Museum's powerful president, Henry G. Marquand, wrote that he feared that "it will overshadow all departments."

If it seemed as though Mrs. Brown and her instruments appeared in New York out of nowhere, the fact is that her family history, as well as a deliberate plan, made her enterprise both logical and possible. Her initial gift—comprised mostly of instruments from the Far East, Middle East, Africa, and the Pacific Islands—was assembled mainly through Mrs. Brown's unceasing correspondence with her husband's international business associates, American government and consular officials abroad, but mostly through her constant communications with a network of missionaries throughout the world.

The Brown and Adams families had longstanding affiliations with the Presbyterian Church, significantly with Union Theological Seminary, well known for training missionaries. Mrs. Brown's father, the Rev. William Adams, was the third president of the seminary, and as a young girl she reported that the household was often filled with visitors from distant places. It is possible that instruments brought as gifts from returning missionaries sparked, what she called, her "fondness for old musical instruments," encouraged her to collect, and was certainly the source of her international world view.

One of the first instruments donated by Mary Elizabeth Brown. Mayuri. 19th century, India. Wood, parchment, metal, feathers; L. 44 in. (112 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.163)

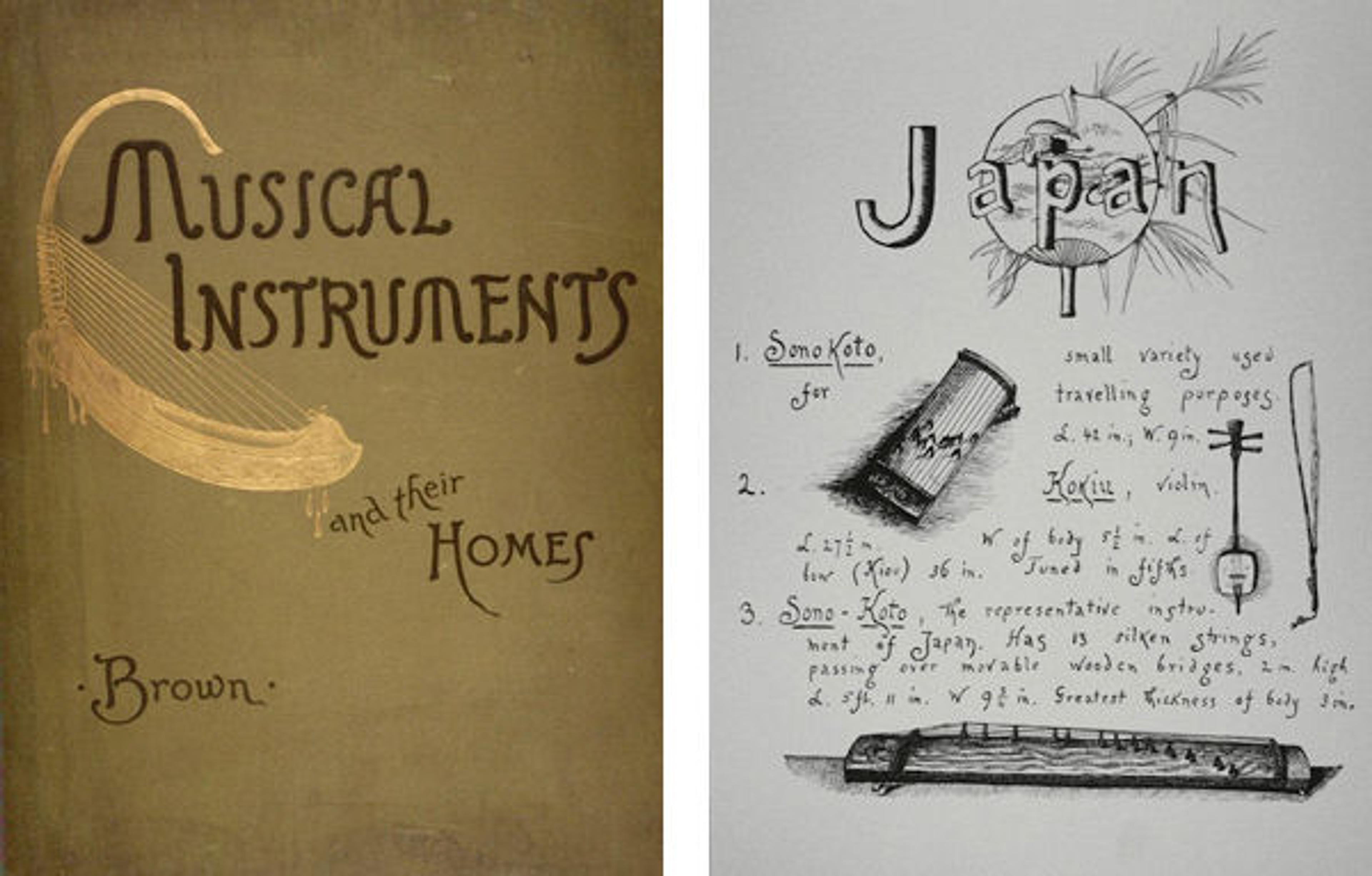

Knowing that she would need to validate her uncommon collection as suitable for the Metropolitan Museum, she took another unusual step. Together with her son, Mrs. Crosby prepared a complete catalogue of her collection, entitled Musical Instruments and Their Homes. Published by Dodd Mead in a large quarto volume in 1888, the catalogue was presented to the Museum in advance of her offer to gift her collection of instruments. Almost 400 pages long, it contained 270 pen and ink illustrations of her instruments by William Adams Brown, many representations of which had never before been seen in America. Unexpected as well were the lengthy chapters on the musical traditions and characteristics of the lands to which her instruments belonged; there was also a lengthy list of authorities and a complete index. As a result, by 1889, Mrs. Brown's collection became the first—and for a while, the only—collection of musical instruments in America that was readily accessible to the public.

Musical Instruments and their Homes; cover (left) and title page for the "Japan" section of the catalogue (right). Images courtesy of the author.

Sally Brown

Sally B. Brown is the co-chair of the Visiting Committee of the Department of Musical Instruments, and the great-granddaughter of Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown.