The Challenges of Collecting North America: Missionaries and Friends

2014 marks the 125th anniversary of the first gift of musical instruments to The Metropolitan Museum of Art by Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown—the beginning of her involvement with the institution that would continue for nearly thirty years, until her death in 1918. In commemoration of the anniversary, Visiting Committee Co-chair Sally Brown, biographer and great-granddaughter of Mary Elizabeth Brown, continues her exploration of Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown's relationship with the Museum and her work to build a collection of over 3,300 instruments for the Met.

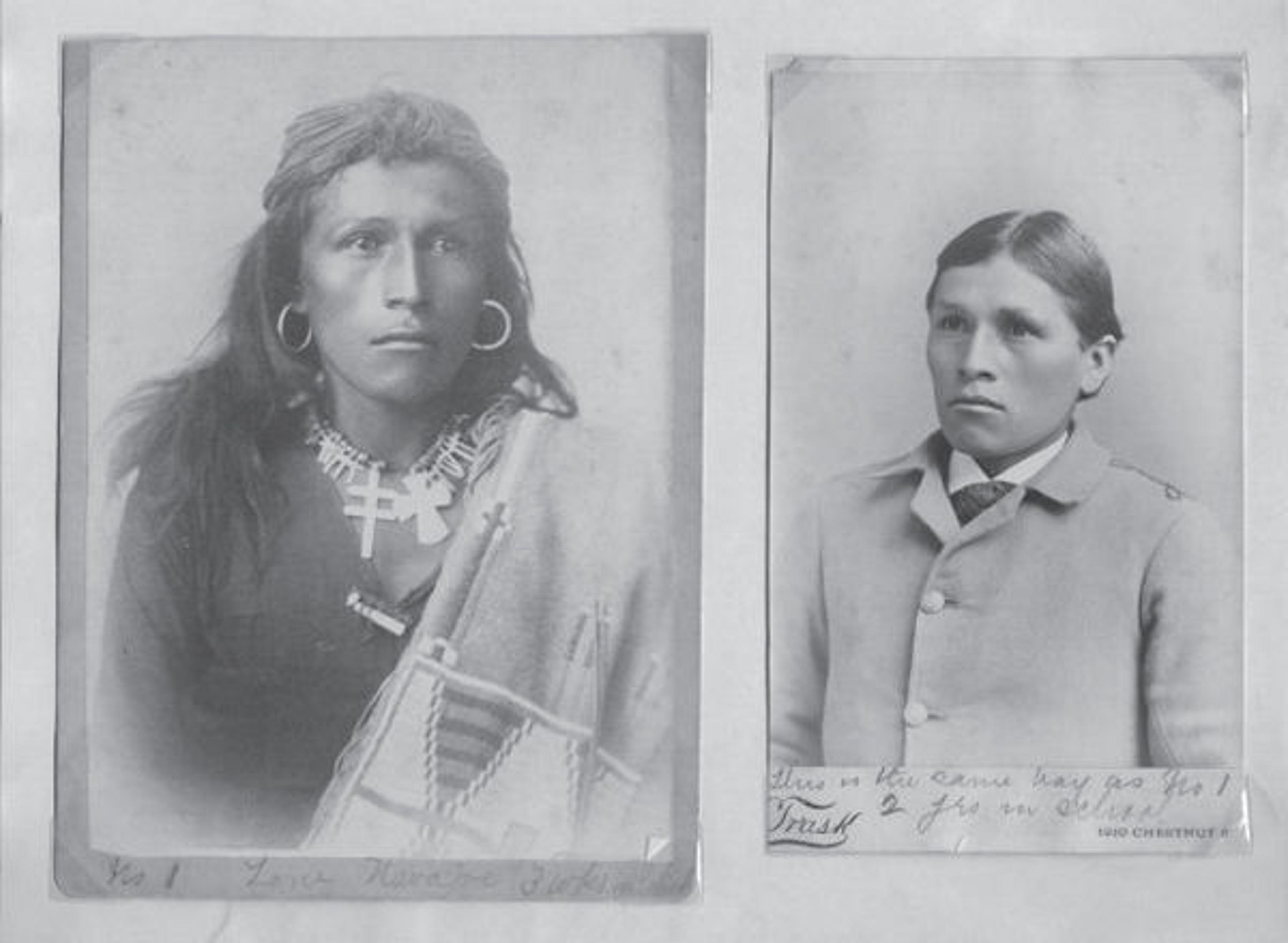

Two photos from Brown's scrapbook depicting a student from the Indian Training School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Her handwritten captions read: "No. 1. Lone Navaho – 3 weeks in school" (left) and "No. 2. This is the same boy as No. 1 – 2 yrs. in school" (right). Image from the Mary Elizabeth Brown Archive, courtesy of the author

«Institutions and individual collectors of musical instruments were active in Europe throughout the nineteenth century. Their interests and collections tended to represent national traditions, though most also had access to instruments from colonies and territories associated with their mother countries. However, it was extremely challenging for Europeans to obtain information and reliable sources for American instruments. The most recent publication from the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs was dated 1860, as was the French Abbé Domenech's Seven Years' Residence in the Great Deserts of North America.»

In 1888, Mary Elizabeth Brown and her son William Adams Brown produced a catalogue illustrating and explaining the first 270 instruments in the Crosby Brown Collection. In it, they commented that the chapter on instruments of North America contained "a considerable amount of information which has never before appeared in print." With the publication of Musical Instruments and Their Homes, collectors and institutions immediately wrote asking to trade or barter American instruments with Brown.

Page from Musical Instruments and Their Homes

Even for Brown, understanding and acquiring American instruments proved to be a difficult and unpredictable enterprise. Her earliest recorded American correspondent was Augusta Moore, a missionary to the Creek, or Muscogee, Indians in Oklahoma, who offered to obtain terrapin shell rattles for Brown, explaining that they had been brought from the Indians' old homes in Georgia or Florida. While the Browns' domestic travels, mostly in the 1870s and '80s, undoubtedly provided the groundwork for Mary Elizabeth's North American contacts, we hear nothing about exchanges or purchases until a trip to Mexico in February 1886. This trip yielded a harp "bought in the city of Mexico" with "the head carved to represent a serpent," which appears in the 1888 catalogue.

The Browns' hosts on that trip were the Frederick Churches living in Mexico City at the time. A year later Church was back in Hudson, New York, sending Brown instruments acquired in Morelia, Mexico, and "New Granada, now Columbia"; one in particular, which he had heard in an impromptu dance performance, "much pleased . . . the effect was novel and very agreeable." He called it a "rattle box" and sent it to Brown "to add to the barbaric part of [her] collection." Church continued to send Brown both Aztec and Central American instruments into the 1890s.

It seems that the Browns' government connections also led to important musical instrument contacts. The family's personal and political support of Grover Cleveland occasioned their acquaintance with William Vilas, initially postmaster general and then secretary of the interior, under which office he controlled the Bureau of Indian Affairs. At the time of their Mexico trip, the Browns made contact with the Indian Training School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where young Native Americans were separated from their indigenous cultures and re-educated to become what were thought to be proper young men and women. Brown, however, was focused on the preservation of pieces of the Native American traditional cultures. In 1887 R.H. Pratt, the founder and supervisor of the school, wrote to Brown:

Dear Madam.

Since sending the Flute one of our Geronimo Apache boys brings me an Apache Violin which I send you today. His name is Lawrence Godelay and the Violin is such as the Apaches of Southern Arizona use. The cost is $1.50. I have your $5.00 check.

Tsii'edo'a'tl, 19th century. Athabascan Family, Arizona, United States. Native American (Apache). Agave flower stalk, wood, paint, horsehair; L. 44.5 cm (17 1/2 in.); Diam. 9 cm (3 1/2 in.); Bow L. 40.7 cm (16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.2631 a, b)

Brown stayed in contact with the Carlisle school, and in 1894 she received the following from Captain Pratt:

I send you today nine Apache fiddles . . . The boys want $1 apiece for these and I guess from the length of time it takes in making them, it is cheap enough. The large round one was made by Geronimo, a prisoner at Mt. Vernon Barracks, Alabama, and given to his son, a pupil here, who recently visited his father.

These bowed stringed instruments, referred to by Captain Pratt as "Apache fiddles," are called tsii'edo'a'tl. Although not one of the instruments sold by Pratt, an extraordinary example can be found in the Museum's collection (shown above), also collected by Brown.

Related Link

Of Note: Posts related to Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown

Sally Brown

Sally B. Brown is the co-chair of the Visiting Committee of the Department of Musical Instruments, and the great-granddaughter of Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown.