Five Things to Know about Atea: Nature and Divinity in Polynesia

View of the exhibition Atea: Nature and Divinity in Polynesia in gallery 359

On view in gallery 359 through October 27, 2019, Atea: Nature and Divinity in Polynesia celebrates the creative ingenuity of Polynesian artists who drew from the natural world to give material expression to their understanding of the divine. Through some thirty examples of figural sculpture, painted barkcloth, rare featherwork, and more, the exhibition offers visitors an opportunity to understand a core principle of Pacific art: the divine is not abstract, but very much alive in nature. Polynesians saw art as a way to communicate with gods and ancestors, and they asserted their genealogical descent from the gods through the creation of temples and ritual regalia produced from materials drawn from the natural environment.

So what makes this a must-see exhibition? Continue reading for five things to know about Atea as you prepare for your visit.

What is Atea? Polynesia's version of the Big Bang.

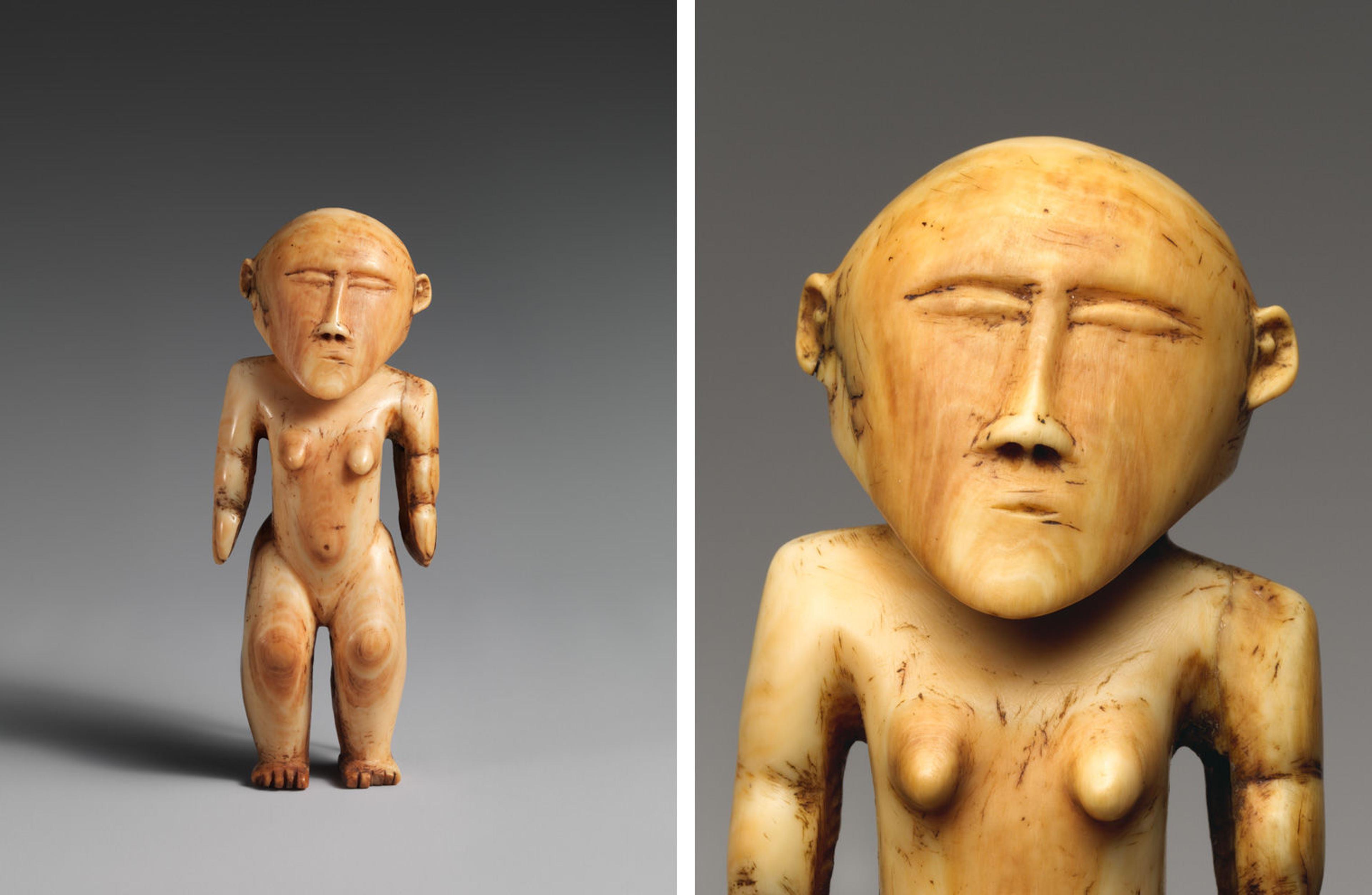

Female figure ('otua fefine), early 19th century. Tonga, Ha'apai Islands. Whale ivory, H. 5 1/4 x W. 2 x D. 1 1/2 in. (13.3 x 5.1 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1470)

Throughout Polynesia, creation stories describe the universe as shrouded in the depths of the long ancestral night. The darkness was thick, dynamic, and potent, and reverberated steadily for many eons until eventually space began to hollow itself out and light began to seep in (atea). The exhibition is grounded in this powerful moment—Polynesia's equivalent to the Big Bang—when light heralded the birth of the universe beginning with the evolution of marine and plant life, birds, fish, and animals. Gods and humans sprang forth from the natural environment—the final generation in the great chain of being, who maintained a close kinship with the natural world.

Brilliance and shimmer enhanced the effectiveness of ritual objects specifically because they referred back to this moment in time. The notion of sacred light is captured and celebrated in one of the great masterworks of Oceanic art in The Met collection: a remarkable shimmering female deity figure carved from a single tooth of a sperm whale.

Whales are considered a manifestation of the divine.

Left: Breastplate (Civavonovono), early 19th century. Fiji. Black pearl shell, whale ivory, coconut fiber, Diam. 9 5/16 in. (23.6 cm). Mark and Carolyn Blackburn Collection, Honolulu, Hawai'i. Right: Whalebone and ivory necklace, late 18th–early 19th century. Austral Islands. Whalebone, whale ivory; coconut fiber, human hair, H. 9 3/4 x W. 9 x D. 1 in. (24.8 x 22.9 x 2.5 cm). Private collection, Gordon Sze

High-ranking chiefs in Polynesia were considered divine because they were direct descendants of the first creator god. Tangaloa, one of four principal deities in Polynesia, presided over the sacred realm of the ocean, and whales were believed to be a manifestation of his presence. Polynesian artists used whalebone and ivory to create spectacular works of art that were believed to contain Tangaloa's divine essence. Wearing a spectacular breastplate or necklace of whale ivory was a powerful way to declare their descent from the god and assert their divine right to rule.

Priests used various objects to create a portal to the ancestral realm.

Flywhisk (tahiri ra'a), early–mid-19th century. French Polynesia, Austral Islands. Wood, coconut fiber, human hair, W. 5 1/8 x L. 32 in. (13 x 81.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1487)

Priests were charged with the dangerous duty of interceding with powerful gods on behalf of their chiefs. Gods were said to pierce through the sky into the earthly realm accompanied by peals of thunder and flashes of lightning. Ritual artefacts known as tahiri were used to summon gods from the dark ancestral realm (te po) where they resided, into the world of light and life (te ao) inhabited by humans. The tahiri above, a flywhisk from the Austral Islands, would have originally featured sparkling attachments of cut pearl shell, which would have jangled when it was spun to attract the gods' presence during ceremonies.

To Polynesians, the crescent shape holds tremendous power.

Feather cape ('ahu 'ula), 19th century or earlier. United States, Hawai'ian Islands. Red feathers ('i'iwi), yellow and black feathers ('ō'ō), fiber ('olonā), W. 31 1/8 x L. 20 13/16 in. (79 x 52.8 cm). Private collection

One of the most distinctive forms in Polynesian art is the crescent shape. You can find it in the arch of a fiber fan, as a design on a feather cape, and even in the dramatic shape and cut of the cape itself. Once you start looking for it, you begin to see it everywhere!

The significance of this shape most likely began as a reference to the plantains and yams that Polynesian islanders presented to their gods in seasonal rites, known as "first fruits" ceremonies, which aimed at ensuring an abundant harvest and productive year ahead. In Hawai'ian, the term hoaka refers to the arc of a rainbow, the raised crest of a helmet, or, more broadly, to the idea of dazzling brightness or a flash of light, which is understood to be a source of divine potency. Hawai'ian chiefs dressed themselves in a series of crescents and arcs, such as the feather cape shown above, to reinforce the idea that they were an embodiment of the divine.

Listen closely: there's chanting in the gallery.

Pendant, 18th–19th century. United States, Hawai'ian Islands. Whalebone, H. 2 3/8 x W. 1 1/2 x D. 1 3/4 in. (6 x 3.8 x 4.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1587)

Polynesians today still rely on the guidance and support of their ancient gods. In the exhibition you can hear four chants recorded by members of a halau (group) from Hawai'i who visited the Museum in summer 2018 and recorded them for us. The group chose to honor their ancestral treasures in the exhibition by reciting these ancient chants that call out to the four principal gods of Polynesia: Ku, Kane, Kanaloa, and Lono.

The chants honor the presence of the gods in the sculptures and art that you see on display in the gallery. For example, Lono is the large temple deity who stands like a sentinel at the entrance to the exhibition, and Kanaloa (also known as Tangaloa, discussed earlier) is the god that presides over the realm of the ocean so he is present in all the art made of whalebone and ivory on display in the exhibition.

Related Content

Atea: Nature and Divinity in Polynesia is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through October 27, 2019.

View a selection of works presented in the exhibition and take a walkthrough of the gallery.

Maia Nuku

Curator Maia Nuku was born in London and is of English and Maori (Ngai Tai) descent. Her doctoral research focused on early missionary collections of Polynesian gods and their extraordinary materiality, which sparked an interest in drawing out the often eclipsed cosmological aspects of Oceanic art. She followed up her involvement on the major exhibition Pacific Encounters: Art and Divinity in Polynesia 1760–1860 (2006) at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts with postdoctoral research at Cambridge University's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, where she served as part of a research team exploring Oceanic collections in major European institutions—Artefacts of Encounter: 1765–1840 and Pacific Presences: Oceanic Art in European Museums.