Assembling a Grand Exhibition: How Visitors to Versailles Came to Life

Pictured here is about one-third of The Met staff who assisted, in some way, in bringing Visitors to Versailles to life

The exhibition Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789) took over half a decade to plan, but was constructed and installed in a mere six weeks. When I began working on the exhibition three years ago as a research associate, I had only an inkling of The Met's myriad specialists, pictured above, who would help us to mount the show.

Each time a show is installed at The Met, walls are pulled down and new ones are put up and painted. Cases and plexiglass vitrines are reused when possible and fabricated to spec when not. Shipments of loan objects, often international, are received at all hours. Every morning before the Museum opens, crates are wheeled into the galleries, where they are unpacked, and the objects within are checked over by conservators before installers fashion special mounts to hold them in place. The team that constructs the cases polishes the plexiglass bonnets inside and out before closing up each case (no one wants to see fingerprints or dust inside a case for three months). Scores of labels are written, styled, copyedited, type set, printed, and pasted at uniform height throughout the exhibition galleries. When all this is done, lighting designers roll through the galleries on rigs that reach up to the spotlights in the sixteen-foot ceilings and make the exhibition sparkle.

Left: View of the "Incognito and Private Visitors" gallery, including partially rolled carpet. Right: Savonnerie Manufactory (Manufactory, established 1626; Manufacture Royale, established 1663). Carpet, 1780–81. French. Wool and linen, 11 ft. 9 3/4 in. x 9 ft. 7 3/8 in. (360 x 293 cm). The Royal Collections Sweden (HGK, TxI 475)

To help this process go as smoothly as possible, in addition to curatorial research, much of my time was occupied with managing loans from around the world, which necessitated corresponding with more than fifty lenders to ensure that we were prepared to display nearly 190 objects properly. Often, this meant tracking down answers that would be necessary for design or installation. Were all of the borrowed paintings glazed? (Paintings that are not framed under glass require stanchions in front of them to protect their surfaces. Ceding even an extra foot of floor space to stanchions can affect visitor footpaths in tight gallery spaces.) Could a Savonnerie carpet on loan from Sweden be displayed partially rolled on its shipping tube, so that it would look the way it did when it was presented as a gift to King Gustav III? The Met's textile conservators suggested making caps to finish off the tube's ends, and asked for the tube's exact diameter. Even more importantly, we needed tube lengths from lenders for all rolled textiles, including two twenty-foot-long tapestries, to know whether they would fit in the elevator. Fortunately, they did!

Textile conservators and installation staff carefully unroll a tapestry in preparation for hanging it on a wall in the "Overseas Embassies" gallery. Workshop of Le Febvre and Matthieu Monmerqué (French, active ca. 1725–1749), after a design by Charles Parrocel (French, 1688–1752). The Departure of the Ottoman Embassy from the Tuileries, 1734–1736/37. Wool and silk, 13 ft. 9 3/8 in. x 19 ft. 2 5/16 in. (420 x 585 cm). Mobilier National, Paris (GMTT/184/2)

Six months prior to installation, close to forty of the key staff who would be involved in building and installing Versailles gathered to discuss the logistics of mounting this multimedia exhibition, which included a mind-boggling array of object types and sizes. At this meeting, we went down the exhibition checklist, and everyone in the room was free to ask questions and make suggestions. The challenges included a three-hundred-pound, thirty-foot-long wool carpet that was to be shown in full—and that had to be unrolled while kept perfectly straight and smooth, all without stepping on it or tugging the corners into place. Many objects, we suspected, would be heavy, although I was surprised by the paperwork for a silver-inlaid cannon that reported the cannon's weight as "2cwt 2qr 3lbs," or 283 pounds for those unfamiliar with imperial measurements.

Installation view of "The Gardens" gallery

Installation view of the "Overseas Embassies" gallery

The polychrome animals in "The Gardens" gallery—made of lead and originally part of thirty-nine operable fountains designed for the labyrinth at Versailles—presented their own challenges. Each one weighs a whopping 1,000 kilograms (about 2,200 pounds). The design of the exhibition called for them to be shown on angled platforms set into niches, which were papered with dense foliage extracted from a seventeenth-century guidebook and mirrored to create a labyrinth-like forced perspective. Setting the fountain figures on these platforms would have required lifting them, however, and the lead was too fragile for that to be a possibility. Instead, we guided them into place on their shipping pallets and then fit the platform decks around their pallets like a collar. To do this, however, we needed to know the heights of their pallets prior to starting construction: if they were too high, the angle of the deck would be too steep and the optical illusion would have been lost. Pallets and crates are not usually made that far in advance, but thanks to the lender and the shipping agent, we got the information we needed in time.

Right: Paintings conservator Shawn Digney-Peer checks the condition of a loan. Nicolas de Largillierre (French, 1656–1746). Conrad Detlev, Count von Dehn, 1724. Oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 28 15/16 in. (92 x 73.5 cm). Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen [Lower Saxony State Museum of Art] (GG 521)

Visitors to Versailles—co-organized by Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide and Bertrand Rondot, curators at The Met and the Château de Versailles, respectively—is largely a show of decorative arts, and yet the checklist includes many paintings, which can be deceptively heavy. If these were to be hung directly on the wall (as opposed to from a hanging rail), the walls built for our exhibition would need to be able to accommodate the weight. It is impossible to guess the weight of a painting, and not all lenders have access to scales. At times, even with reinforced walls, heavy paintings might still need support brackets, made on the spot by the Museum's machine shop. What is more, not all hanging hardware is made the same way. What is commonly used by our European lenders, for example, is not readily available in the United States and had to be sent to New York along with the paintings. Frames come in all shapes, sizes, and ages, too. Predictably, the older frames were sometimes slightly out of true (or unaligned), which raised a dilemma: should we adjust the painting so that the painted image was level, or the top of the frame? What would catch a visitor's eye more?

As with specific hardware or mounts, lenders usually send dress forms with costume loans. These mannequins are extremely helpful because they arrive preadjusted to fit a specific costume, saving conservators' time during installation, and also because The Costume Institute at The Met has a limited supply of mannequins designed for eighteenth-century costume. At the same time, these dress forms can complicate planning because they're not all alike: They come in many colors. Some have heads, hands, and legs. Some have visible supporting poles. Others don't.

Installation view of the "Getting Dressed for Court" gallery

The Met's costume conservators and dressers work hard to ensure that the costume installations look as uniform as possible. In one instance, it was not possible to source the correct type of mannequin in advance, so our dressers padded out a female dress form to fit the justaucorps (livery jacket) once worn by a palace employee.

Further complicating the matter, not everything installed in the costume case, strictly speaking, is a costume. Smallswords, which were indispensable for a man's court attire and were best exhibited alongside the men's habits à la française, were mounted by conservators in the Department of Arms and Armor to match the mannequins' bases. The doll's court gown (lent by the Fashion Museum, in Bath, England) is attached to a supporting board that needed to be covered in fabric to match the interior of the display case. Of course, solving one problem always raises another: we had to finalize the color for all case fabrics and send a large swatch to England with only a week to spare before the dress was packed up and shipped to New York.[1]

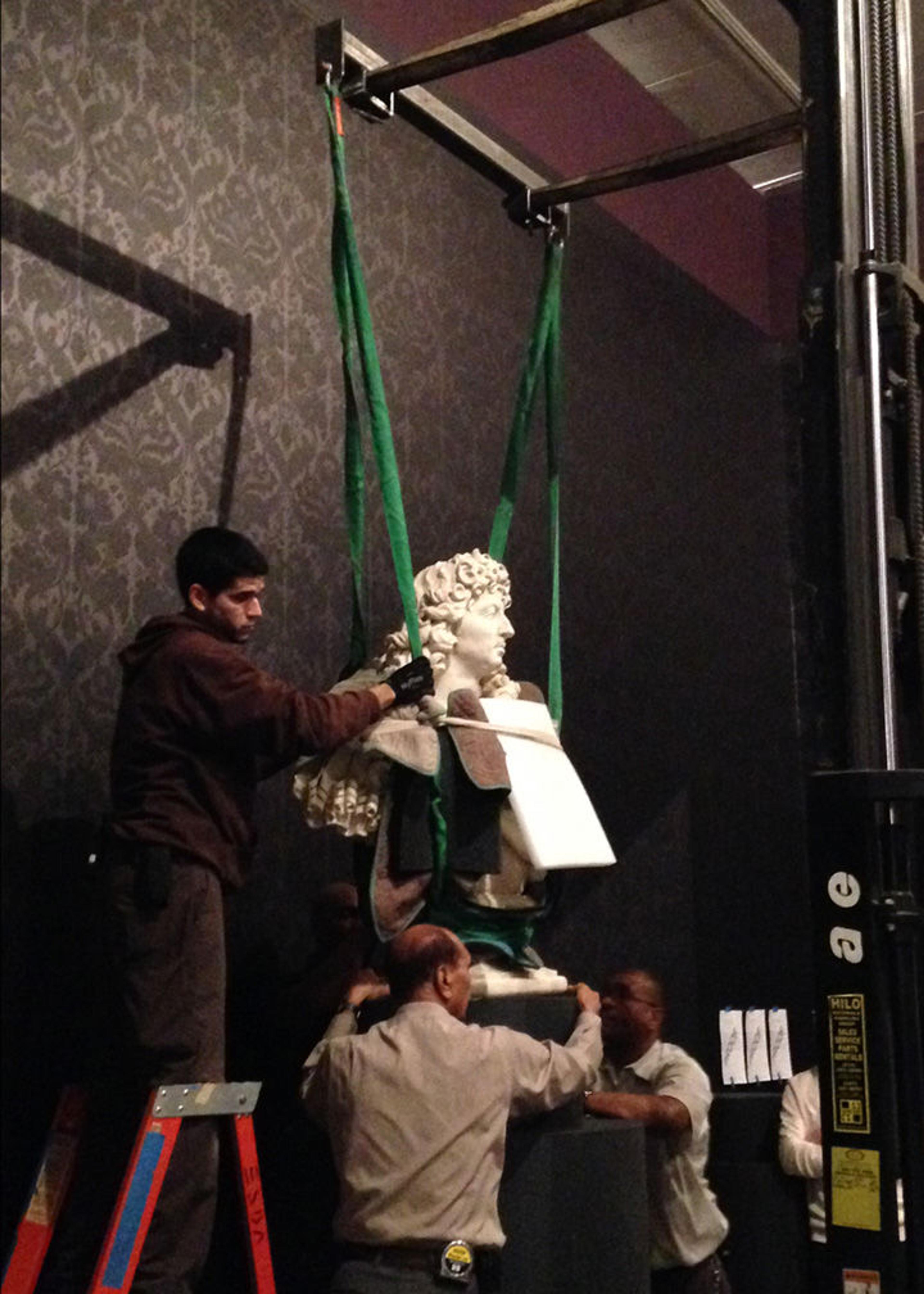

Riggers using straps to install a portrait bust of Louix XIV in the "To See the King" gallery. Antoine Coysevox (French, 1640–1724). Louis XIV, 1678–81. Marble, 47 1/4 x 37 3/8 x 13 3/8 in. (120 x 95 x 34 cm). Musée National des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon (MV 789)

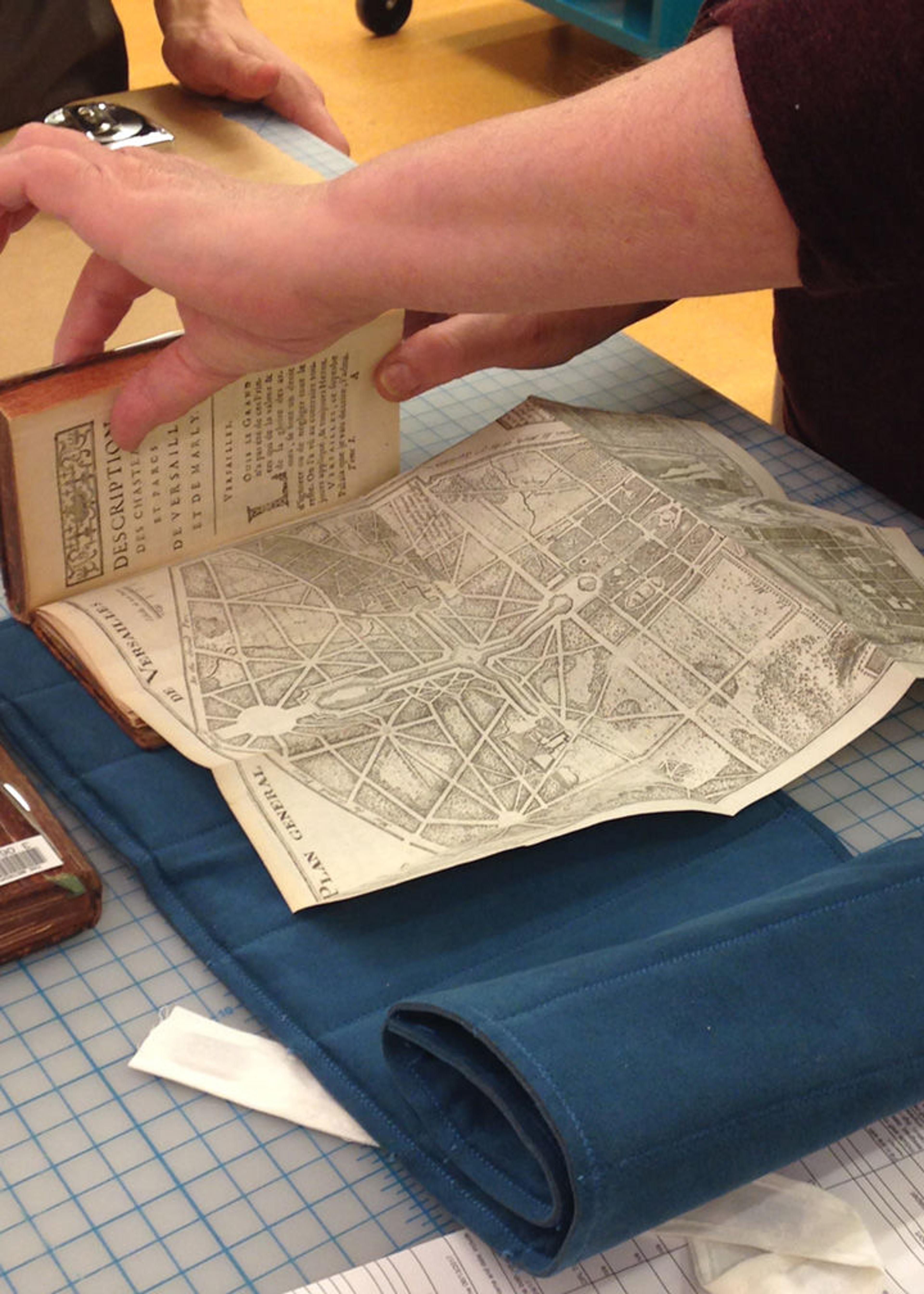

A conservator tests the opening angle ideal for the book's spine and foldout, before measuring for a cradle. Jean-Aimar Piganiol de La Force, Nouvelle description des chateaux et parcs de Versailles et de Marly . . . (Paris: Chez la Veuve de Florentine Delaulne, 1724).

A curator's goal is to show each object to its best advantage, in the service of the story told by an exhibition. But importantly, this must be done without compromising the condition of an object, which can often be delicate. Each artwork has its own set of needs, and not every eventuality can be anticipated. Sometimes, these needs compete with the curatorial and design vision, the realities of construction, and the conditions necessary for the object's safe display. Textiles and works on paper, for example, might need lower light levels to prevent fading. Silver may need to be displayed in a sealed, humidity-controlled case to keep it from tarnishing. Books require bespoke cradles to support them properly, and it is rarely possible to make these in advance: they need to be measured, and to have the flexibility of their spines assessed, in person. In the case of several of our exhibition's guidebooks, extra support for foldout pages had to be added.

Installation view of the "Tourists and Souvenirs" gallery

The display requirements for each loan can be further complicated by the logistics of coordinating its delivery with other objects being installed in the same case—a series of unique challenges that Exhibitions Registrar Meryl Cohen wrote about in a recent article on Now at The Met. By far the trickiest day of installation was when we closed the case in the "Tourists and Souvenirs" gallery. This cantilevered case—designed with a gently sloping deck, and filled chockablock with assorted ivory buttons, folding fans, snuffboxes, and works on paper of the type that tourists might have purchased to remember their trip—is one of the most charming in the exhibition.

Due to courier schedules, we had only one day to unpack and pin everything in place before the case could be closed. The long case bonnet, though fabricated in two pieces, was extremely heavy, and each half took six people to lift into place. Once installed, its top was quite high. After a chicken-and-egg debate about whether to hang paintings above the cantilevered case before the bonnets were placed (easier to hang) or after (easier to lift the plexiglass into place), our paintings technicians determined it would be safer to install and level each canvas above the closed plexiglass vitrines.

Riggers and installation staff align The Departure of the Ottoman Embassy from the Tuileries.

Who, then, are all the people in the photo at the start of this post? They are exhibition designers, who produce architectural drawings, case drawings, and graphics ranging from wallpaper to labels; they are the buildings and construction staff, who build everything from walls to cases, and who work out all manner of logistical puzzles; the registrar, who coordinates shipping, receiving, and installing the art; the packers, who open crates, remove the complicated internal bracing that holds an object in place, and put it all back together again; the riggers, who lift, move, and install heavy or oversized artworks, and are in tremendous demand throughout the Museum every day; the machinists, who fabricate steel brackets, hooks, or clips needed to secure large works; the conservators, who condition check every object and ensure that each is safely displayed; the installers, who make mounts to support small objects, from porcelain saucers to folding fans; the fabricators at the plexiglass shop, who make vitrines and book cradles; the exhibition project manager, who coordinates all these staff members and oversees budgets; the collections managers and art technicians, who hang paintings and drawings, hoist tapestries on cables, mount small objects, ensure all details and requirements are met, keep the galleries dust-free during the show, and problem-solve generally; security officers; and lighting designers, who unify the design in the face of challenges like the low-light levels necessary to preserve Benjamin Franklin's suit.

This photo also includes other Museum staff whose work preceded installation: the producers of the Audio Experience, which Managing Editor and Producer Nina Diamond has written about at length; the editors of the exhibition's website and its blog series; the video editors and producers; and the catalogue editors, production manager, and bibliographer. Not to forget the exhibitions office, legal team, development officers who raised the funds to make the exhibition possible, staff photographers, press officers, educators, librarians, and the numerous conservators, art technicians, and curators across the building who lent their expertise. These invaluable staff members display a level of professionalism and decades of experience, not to mention practical know-how, spatial reasoning, calm under pressure, remarkable creativity, and enthusiasm. It is thanks to them that curator Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide's vision for putting The Met's visitors in eighteenth-century shoes, as it were, resulted in our being able to build Versailles at The Met.

Note

[1] The conservation of various costumes and the conservation of arms and armor will be the subjects of two upcoming blog posts, by Sarah Scaturro and Cassandra Gero, and by Edward Hunter, conservators in The Costume Institute and the Department of Arms and Armor, respectively.

Related Content

Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789) is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 29, 2018.

Learn more about the binaural audio experience and view the exhibition galleries.

Learn more about Visitors to Versailles in a blog series published in conjunction with the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase at The Met Store.

Elizabeth Benjamin

Elizabeth joined The Met in 2015, and since 2018 has edited exhibition labels and catalogues in the Publications and Editorial Department. She holds a PhD in Art History from Northwestern University, with a focus on nineteenth-century European painting and the domestic interior, and earned her B.A. in Art History and French from the University of California, Berkeley. Previously she worked for Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra in San Francisco.

Selected publications

“All the Discomforts of Home: Caillebotte and the Nineteenth-Century Bourgeois Interior.” In Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, edited by Mary G. Morton and George Shackelford, 85–98. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2015.

“The Modern Interior Stripped Bare: Gustave Caillebotte’s Intérieur Démeublé.” In Visualizing the Nineteenth-Century Home: Modern Art and the Decorative Impulse, edited by Anca I. Lasc, 122–38. London and New York: Routledge, 2016.

Review of Gustave Caillebotte: Painting the Paris of Naturalism, 1872–1887, by Michael Marrinan. CAA.Reviews, May 29, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.3202/caa.reviews.2019.54.