When Thomas Cole Caught "Panoramania"

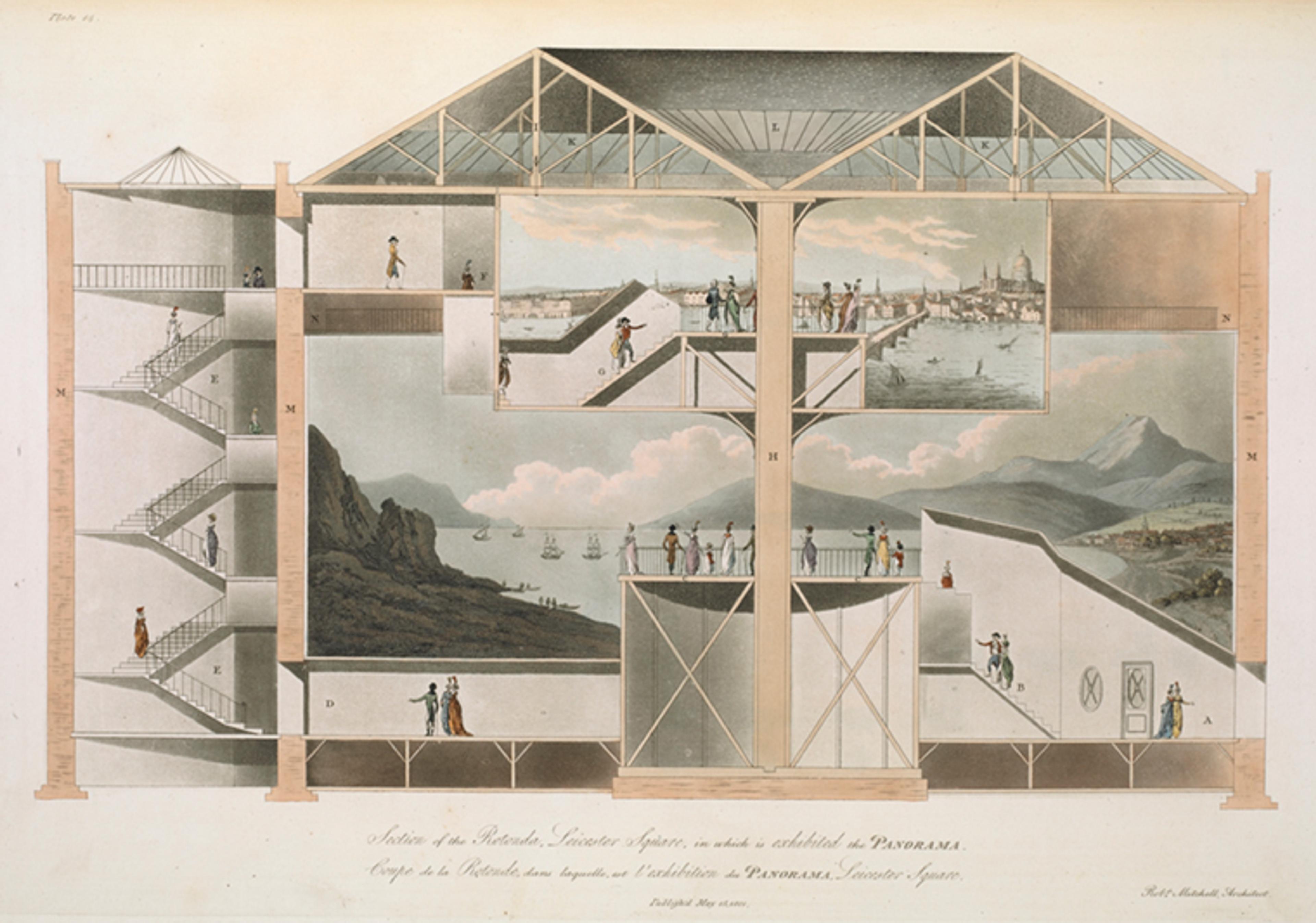

Anonymous. Section of the Rotunda, Leicester Square, 1801. Etching, colored aquatint. Published by Robert Mitchell, London. British Library (56.i.12 [Plate 14]). Public domain image via British Library.

«The landscape paintings of Thomas Cole, J. M. W. Turner, and John Constable seen in Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings are notable for their splendid gold frames, whose elaborate mouldings provide a boundary to the splendid vistas that open up within. Yet haunting the exhibition is another art form, almost entirely lost and forgotten in the twentieth century—a medium in which art burst out from the frame and entirely surrounded the viewer. It was known as the panorama.»

Admired by Cole and his English contemporaries, panoramas were huge circular paintings, often several hundred feet long. The panorama's purpose was to create, from a central viewing platform, a completely convincing illusion of reality in all directions—an unprecedented immersive experience uncannily predictive of virtual reality today. The public in London and New York went wild for the new medium and "panoramania" had taken hold on both sides of the Atlantic by the 1820s.

Customers would enter on street level, pay a small fee, and climb a flight of stairs after moving along a dark corridor. At the top, they emerged into another world. Presented in purpose-built theaters of display, panoramas were lit from above by invisible skylights. The view of the painting, through 360 degrees, was unimpaired and the viewer could survey the surrounding scene with a magisterial gaze hitherto the privilege of a tiny elite who could afford to travel.

John Vanderlyn (American, 1775–1851). Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles (detail), 1818–19. Oil on canvas, 12 x 165 ft. (3.6 x 49.5 m). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Senate House Association, Kingston, N.Y., 1952 (52.184)

The panorama was invented by the English painter Robert Barker, who showed the first example in Edinburgh in 1787, but the form reached maturity with the opening of a full-scale panorama in 1793. It stood in London's Leicester Square, then as now the heart of the entertainment district. Section of the Rotunda, Leicester Square, in which is exhibited the Panorama, published by Robert Mitchell in 1801, indicates the ingenious architecture whereby two panoramas could be displayed simultaneously. By 1795, a panorama of London was showing on Greenwich Street, New York, in a purpose-built gallery about eighteen feet high and one-hundred-thirty feet in circumference. John Vanderlyn constructed a neoclassical rotunda in City Hall Park, New York, in 1819 and installed in it a panorama of Versailles, which can be seen today at The Met in gallery 735. By popular demand, panoramas were regularly replaced so that repeat visitors would be rewarded with new and ever-more exciting visual fare.

We can be sure that Thomas Cole visited Vanderlyn's panorama during his years in New York, 1825 through '29, and that he hurried to Robert Burford's panorama of Pandemonium, from Milton's Paradise Lost in the Leicester Square building when he arrived in London in 1829. While sketching in Italy in 1832, Cole even dreamed of designing a panorama of his own, depicting the Bay of Naples.

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View of Round-Top in the Catskill Mountains, 1827. Oil on panel, 18 5/8 x 25 3/8 in. (47.31 x 64.45 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865

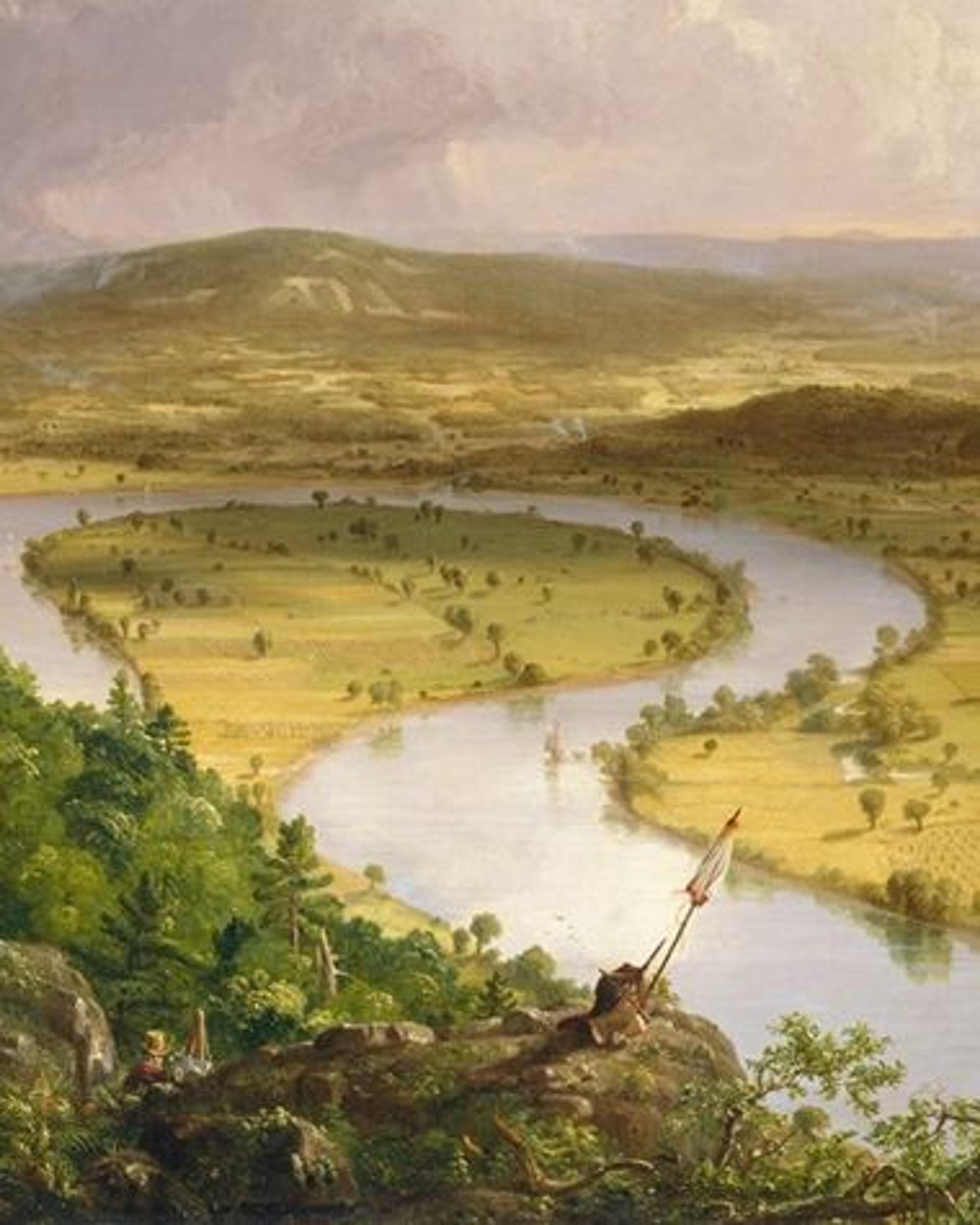

Although there is no surviving panorama design by Cole, his works—and those of his British contemporaries—are deeply touched by the visual logic of these massive circular works, whose endless horizons defeat the constricting limits of the gilded frame. There is a hint of the panorama in Cole's breakthrough work of 1827, View of Round-Top in the Catskill Mountains, in which a strange outcrop of rock in the foreground commands a magnificent view of the Hudson Valley and the foothills of the Catskills. It is as if Cole invites us to step out on the rock, to stand at the center of the amphitheater created by the dramatic hillsides.

John Constable (British, 1776–1837). Hadleigh Castle, The Mouth of the Thames—Morning after a Stormy Night, 1829. Oil on canvas, 48 x 64 3/4 in. (121.9 x 164.5 cm). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This concept is pushed further in a late masterpiece of John Constable, Hadleigh Castle, also shown in Thomas Cole's Journey, which made a profound influence on Cole when he saw it in London at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1829. In Constable's turbulent painting, the ruined, circular tower offers a magnificent view of the Thames Estuary as storm clouds roll away. The tower was indeed used as a real vantage point by customs-men on the lookout for smugglers arriving by boat. Its relationship to the uninterrupted flat expanse of the horizon exactly parallels that of the viewing platform and the painted panorama.

Watch a video featuring time-lapse photography of the installation of Cole's The Course of Empire

Cole's career reached its height in 1836, as he completed the great five-part series The Course of Empire and The Met's celebrated canvas View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow. Although The Course of Empire was originally placed with the four outer panels double-hung, it becomes clear in the present installation that Cole envisaged the series being arranged, ultimately, in a horizontal sequence. Betsy Kornhauser, curator of Thomas Cole's Journey, suggested the deployment of angled walls so that a visitor to the exhibition is immersed in the series, rather as Cole or his contemporaries might have been as they stood on the viewing platform. Placed in exhibition designer Brian Butterfield's hands, The Course of Empire has never been seen to better effect.

Although The Course of Empire offers five separate views of the same landscape as it changes through time, the visual logic of the whole sequence demands that it be taken in at a single glance before the viewer begins to explore the wealth of detail within each work. The horizon line is consistent throughout the entire series, such that the eye can follow it with a circular, scanning motion that filmmakers, in homage to the panorama, call a "panning shot."

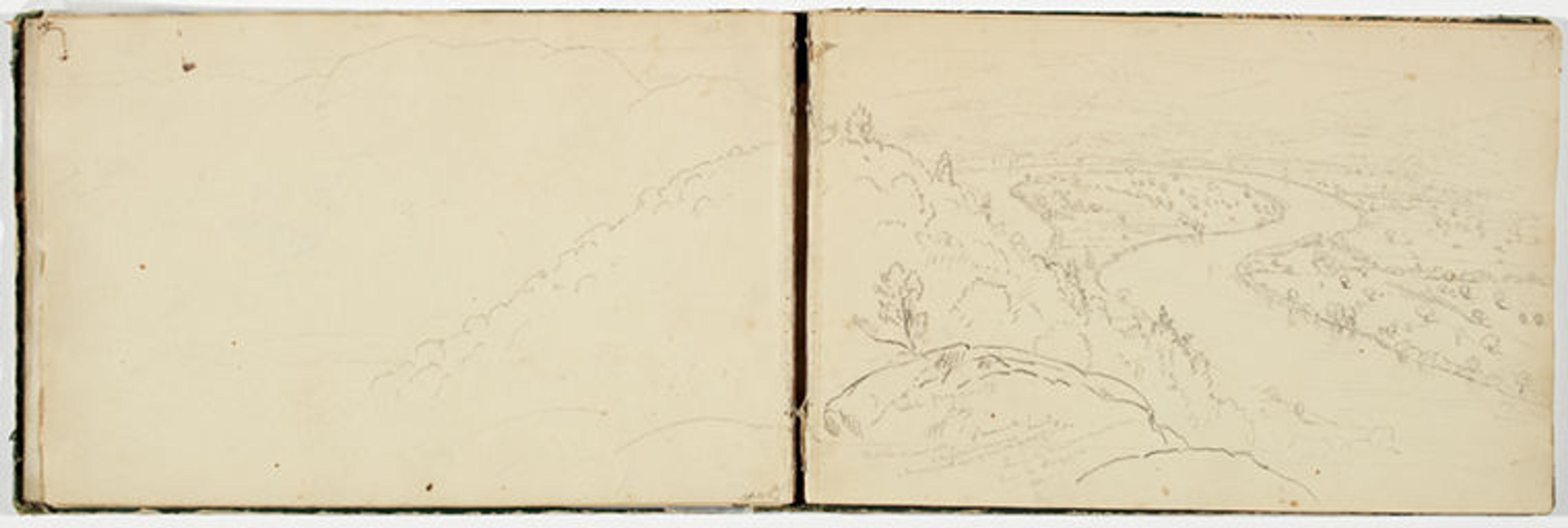

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). Panorama of the Oxbow on the Connecticut River as Seen from Mount Holyoke, ca. 1833. Graphite pencil on off-white wove paper, 8 7/8 x 13 1/2 in. (22.5 x 34.3 cm). Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, William H. Murphy Fund (39.566.66)

The panoramic effect is perhaps found at its most impressive in The Oxbow, which derives from a bold pencil sketch, made in 1833, that extends laterally across the gutter of a sketchbook, tailing off halfway across the left page in a manner that implies further vistas beyond. In the finished painting, Cole includes a tiny self-portrait in the foreground, amid the lush vegetation of Mount Holyoke. Turning toward us, as if sharing a comment with a companion on the viewing platform, he has been sketching from the broad valley landscape that opens up beyond—a view within which is inscribed a great historical truth about the moral and ecological dangers of swift transformation of wilderness into cultivated land.

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (detail), 1836. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 76 in. (130.8 x 193 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908 (08.228)

The strangely sudden transition from foreground leafage to the distant valley below resembles the panorama's jarring gap between platform and painting beyond—a problem that was rectified later in the nineteenth century by the inclusion of carefully proportioned, illusionistic sculptural elements (realia) to fill the gap. Cole's panoramic vision, then, was not as simple as that of the illusionistic painters in Leicester Square; rather, mixing low and high culture, he appropriated the visual logic of the panorama as a central device of a new and ambitious mode of painting—the American sublime.

Related Content

Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 13, 2018.

Read a blog series about Thomas Cole on Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Thomas Cole, including a walkthrough of the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase in The Met Store.

John Vanderlyn's Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versaillesis on view at The Met Fifth Ave in gallery 735.

Tim Barringer is Paul Mellon Professor and Chair of the Department of the History of Art at Yale University, and co-curator of Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings at The Met.

Tim Barringer

Tim Barringer is Paul Mellon Professor and Chair of the Department of the History of Art at Yale University, and co-curator of Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings at The Met.