Modern Pigments Found in Thomas Cole's Paintings Shed New Light on the Artist's Practice

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). The Course of the Empire: The Consummation of Empire, 1835–36. Oil on canvas, 51 1/4 x 76 in. (130.2 x 193 cm). New-York Historical Society, Gift of The New-York Gallery of the Fine Arts (1858.3). Digital image created by Oppenheimer Editions

«At first glance, The Oxbow and The Consummation of Empire, two masterpieces by Thomas Cole prominently featured in the exhibition Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings, seem entirely unrelated paintings, both in subject and content. However, the research carried out in preparation for the exhibition established a very close connection between the two masterpieces. This blog post focuses on the specific pigments Cole selected to create the richly beautiful and subtle range of colors exhibited in the two paintings and the analytical means used to detect the pigments.»

Watch a brief video highlighting insights gained from the technical investigation. Transcript available on MetMedia.

In the summer of 2016, the New-York Historical Society delivered The Consummation of Empire to the Department of Paintings Conservation for a technical investigation. The investigation of the two paintings (The Oxbow is in The Met collection) included examination of the surfaces of the paintings with the stereomicroscope, as well as imaging techniques including X-radiography and infrared reflectography (IRR). A few microscopic paint samples were removed from the edges of both compositions in order to obtain specific information regarding the ground preparations and paint layers. In addition, scanning X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy produced maps of the elements that helped to identify the pigments Cole used to paint these magnificent depictions. An essay in the exhibition catalogue focuses on the relationship of the two paintings and provides insights into the artist's creative process.

Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, 1836. Oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 76 in. (130.8 x 193 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Russell Sage, 1908 (08.228)

Exhibition co-curators Elizabeth Kornhauser and Tim Barringer have eloquently described Cole's great concern for the destructive aspects of the Industrial Revolution and the potential consequences of these advancements on nature and civilization. Despite these misgivings, Cole was quick to embrace a range of pigments newly introduced to the artist's palette, which were a direct benefit of advances in science and industry in the early nineteenth century. In addition to using pigments that had been available to artists since ancient times—for example, ultramarine blue, vermillion, red, yellow and brown earth pigments, lead white, and carbon-based black—we detected his use of cobalt blue, chrome yellow, zinc white, and Prussian blue. By the end of the eighteenth century and into the first decades of the nineteenth century, the expanding chemical and metallurgical industries, primarily in France and Germany, resulted in the invention of synthetic inorganic materials based on cobalt, chromium, and zinc.

While it is possible that Cole obtained newly available, very modern pigments from artist colormen operating in New York City, it is more likely that he purchased these during his travels in Europe to London, Paris, Florence, and Rome in the early 1830s, where they were manufactured. Artist materials had been imported into America from Europe since the eighteenth century, so one cannot rule out the possibility that Cole obtained imported pigments in New York—although the artist supply chain in America was not reliably established until the mid- to late nineteenth century. For example, we know from artists' correspondences that they routinely had trouble getting a good-quality, pure drying oil (linseed) in the United States.

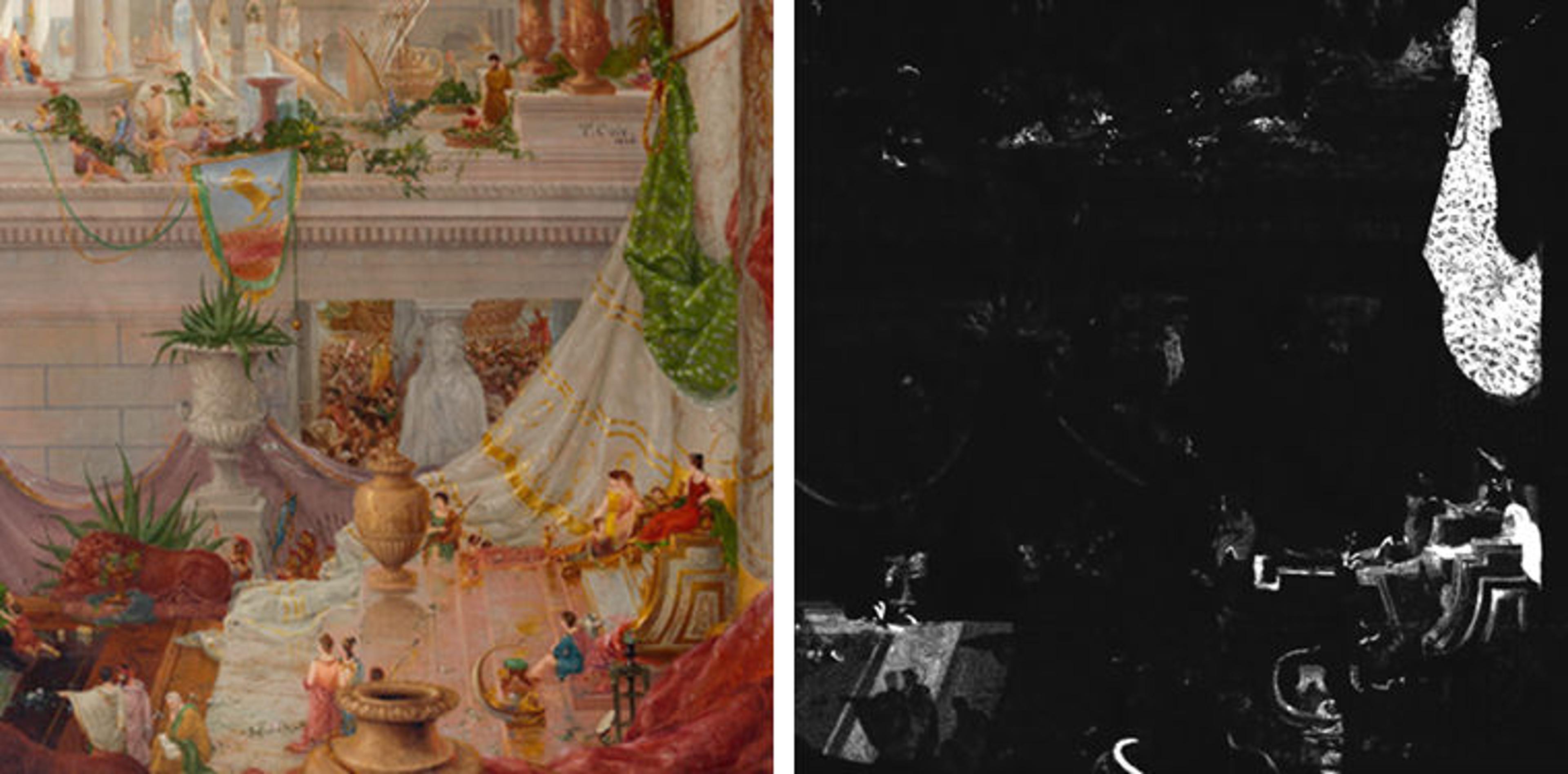

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). The Course of the Empire: The Consummation of Empire (detail). Right: Cobalt distribution map obtained by X-ray fluorescence (XRF)

Cobalt blue (CoO.Al₂O₃) is a very stable, bright-blue pigment that was generally available by the early 1800s. Although it was expensive when first introduced, it was less costly than the highly esteemed, natural ultramarine-blue pigment. It was not until 1828 that a process was revealed to manufacture a synthetic form of ultramarine blue.

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). The Course of the Empire: The Consummation of Empire (detail). Right: Chrome distribution map obtained by X-ray fluorescence (XRF)

Artists had struggled for centuries to produce a broad range of green colors with the pigments that were available. In the nineteenth century, the development of chrome yellow resulted in a remarkable improvement to the artist's palette—particularly for landscape painters. Chrome yellow (PbCrO₄.xPbO) was generally available by 1815 and, although expensive, it was esteemed for its bright-yellow color. Cole combined chrome yellow with Prussian blue to achieve a very desirable bright green. While Cole could have mixed these two pigments together before grinding them in a linseed-oil medium to produce paint, it is also possible that he bought an industrially produced mixture of these two dry pigments known as "chrome green."

Left: Thomas Cole (American, 1801–1848). View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (detail). Right: Zinc distribution map obtained by X-ray fluorescence (XRF)

Zinc white (ZnO) entered the artist's palette around 1850, primarily for use in watercolor. Therefore, Cole's use of zinc-white ground in an oil medium in The Oxbow, which was painted in 1836, presents us with a relatively early use of this pigment. It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that zinc white was prepared by artist colormen as an oil paint, so Cole surely prepared this color himself by grinding dry pigments in linseed oil (as he did with many of his colors), rather than buying his colors premixed from an artist colorman.

Our discovery that Cole used many of the latest pigments available in Europe in the 1820s and '30s for his paintings of the period strengthens and adds to the argument that the exhibition lays out—that Cole's journey to Europe from 1829 to 1832 not only greatly advanced his artistic ability, but also exposed him to the most recent artist pigments, which he was quick to embrace.

Related Content

Thomas Cole's Journey: Atlantic Crossings is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through May 13, 2018.

Read a blog series about Thomas Cole on Now at The Met.

See more digital content related to Thomas Cole, including a walkthrough of the exhibition.

The exhibition catalogue is available for purchase in The Met Store.

Dorothy Mahon

Dorothy Mahon is a conservator in the Department of Paintings Conservation.

Silvia Centeno

Silvia A. Centeno is a research scientist in the Department of Scientific Research.

Louisa Smieska

Louisa Smieska is the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Scientific Research.