Dangerous Beauty in the Ancient World and the Age of #MeToo: An Interview with Curator Kiki Karoglou

Curator Kiki Karoglou at the entrance to the exhibition, in gallery 172. Photo by Will Fenstermaker

Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art, a gem of an exhibition tucked away on a mezzanine at The Met Fifth Avenue, is mesmerizing viewers and reviewers alike. I went into the gallery with exhibition curator Kiki Karoglou to find out why. In this interview, Kiki shares provocative insights into the relevance of mythological hybrid beings and offers a behind-the-scenes look into the making of the exhibition, which is on view through February 24, 2019.

Sumi Hansen: The original subtitle of the show was The Female Monster in Classical Art and Myth, but it was changed to Medusa in Classical Art. What happened?

Kiki Karoglou: The fantastical creatures in the show are not monsters in the modern sense, but hybrids, or mixed beings. The Greeks viewed them as "signals" or "warnings," a meaning that carried over into the Latin monstrum, from which the English "monster" is derived. Imbued with protective powers, they functioned as apotropaia, literally, "turners away."

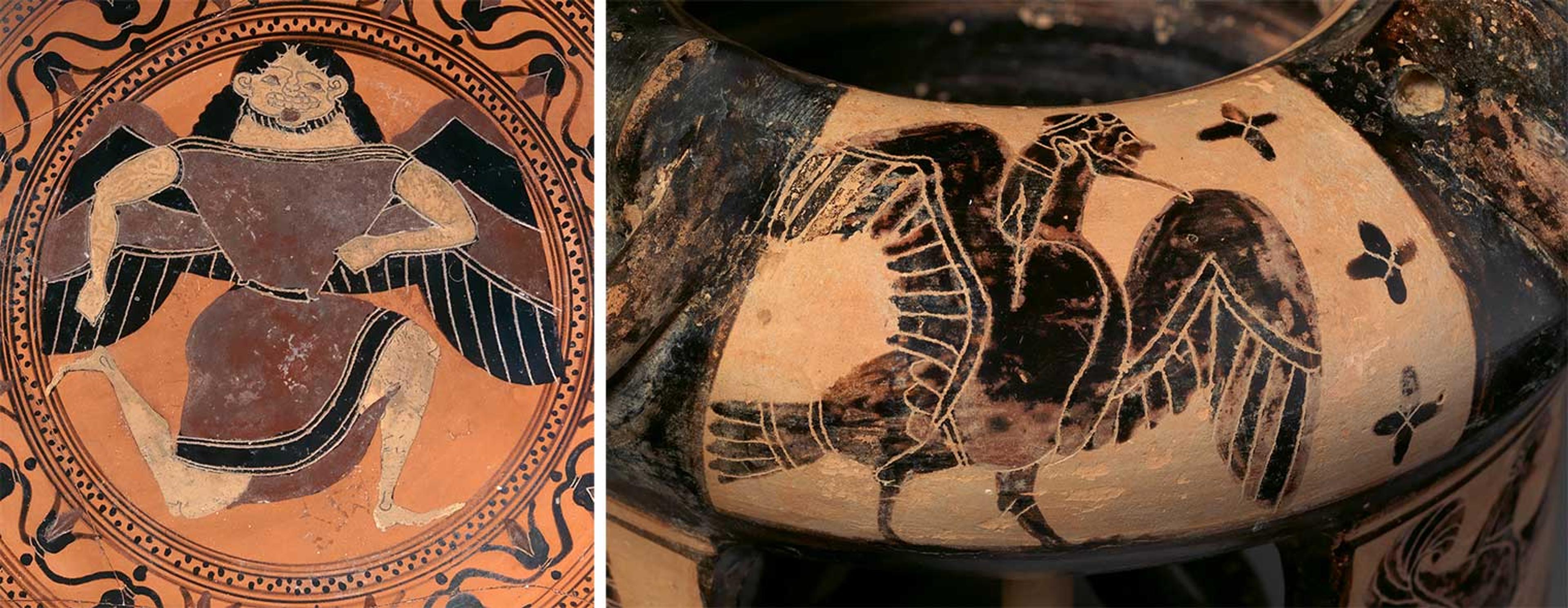

Left: Terracotta kylix: Siana cup (drinking cup) (detail), 575 B.C. Attributed to the C Painter. Greek (Attic), Archaic. Terracotta; black-figure, H. 5 1/8 in. (13 cm); diameter 9 5/8 in. (24.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1901 (01.8.6). Right: Terracotta tripod kothon (vessel for perfumed oil) (detail), mid-6th century B.C. Attributed to the Group of the Boeotian Dancers. Greek (Boeotian), Archaic. Terracotta; black-figure; H. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm); diameter 7 1/8 in. (18.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1960 (60.11.10)

In the archaic period (700–480 B.C.), these composite creatures were monstrous, but they were also androgynous. Their gender is ambivalent: they are represented as either male or female. On this archaic terracotta cup [above left], Medusa has a beard. If you look at the siren on this vessel for perfumed oil [above right], she also has a beard. Later, the figures are feminized and made beautiful.

From the fifth century on, the iconography of the hybrids is settled and they are always portrayed as female. That's when they become more human, and more beautiful. Yet even when they are beautiful, these composite beings still have a terrifying power. Medusa's gaze, the sirens' song, and the sphinx's riddle are all extremely dangerous. Thus, Dangerous Beauty.

Tell us the story of the exhibition. Where does it begin, and where does it end?

The exhibition looks first at late archaic predecessors from late sixth-century Greece, then at the transformation of the monsters in the classical period. From there we move on to neoclassical works and then into the twentieth century, with the designer Versace.

There are two key pieces without which the show couldn't exist:

Left: Pelike (jar) with Perseus beheading the sleeping Medusa, ca. 450–440 B.C. Attributed to Polygnotos. Greek (Attic), Classical. Terracotta; red figure, H. 18 7/8 in (47.8 cm); diameter 13 1/2 in. (34.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1945 (45.11.1). Right: Chariot-pole finial with the head of Medusa, 1st–2nd century A.D. Roman, Imperial. Bronze, silver, copper, 7 1/4 x 7 1/8 x 4 1/4 in. (18.3 x 17.9 x 10.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1918 (18.75)

The first is a fifth-century Greek red-figure vase in which Medusa is portrayed as an attractive young woman being decapitated. This is one of the earliest renderings of the beautiful Medusa in Greek art. The other is a Roman ornament, a finial from a chariot pole, which is the signature piece for the exhibition. I built the show around these two works. In fact, I could have stopped the show there, for Medusa, at least! These two pieces tell the whole story, from the gruesome decapitation of an attractive young woman to the beautiful human head that turns men to stone.

Left: Terracotta stand, ca. 570 B.C. Signed by Ergotimos as potter; signed by Kleitias as painter. Greek, Attic, Archaic. Terracotta; black-figure, H. 2 1/4 in. (5.7 cm); diameter 3 9/16 in. (9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1931 (31.11.4). Right: Fragment of a relief with Achilles carrying a Gorgon shield, ca. 600 B.C. Greek (Attic), Archaic. Terracotta, 16 1/2 x 9 7/8 x 1 1/2 in. (42 x 25 x 3.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Samuel D. Lee Fund, 1942 (42.11.33)

Is Medusa a true hybrid? The other hybrids in the exhibition have animal body parts, but she's just a head.

She's a hybrid because of the boar tusks, wings, and snakes in her hair. The artistic challenge was to represent something so hideous and terrifying to behold that you're turned into stone. In the archaic period, Greek artists came up with the motif of a frontal female face with glaring, bulging eyes, fangs, snakes, a wide grin, and a lolling tongue [above left]. Medusa's grotesque face is often employed as a device on shields to frighten and paralyze the enemy. The imposing Gorgon head occupies almost the entire surface of Achilles' shield [above right].

In antiquity, Medusa had human hair often entwined with snakes; but after the Renaissance, serpents replaced her hair altogether. Vasari attributes this innovation to Leonardo da Vinci, telling us that as a young man Leonardo painted a frightful Medusa with snakes for hair. Caravaggio used this motif on his famous painted wooden shield, and today we find it in popular movies, such as Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010), where Uma Thurman, who plays Medusa, has snaky hair.

In the publication that accompanies the exhibition you speculate that the hybrids are a metaphor for the dangers and anxieties that confront human beings. But why are these gendered female?

We can't just say "misogyny" and that's the end of the story. But I do think it has to do with fear. In a male-centered society like ancient Athens, the feminization of monsters comes hand in hand with the demonization of women. It's an issue of control of female sexuality and power. In ancient tragedy, for example, when the powerful deviant queens Clytemnestra and Medea are wronged by men and overcome with rage, they commit monstrous crimes, and they are compared to Medusa and other female monsters and beasts. In a later source, hetairai—cultured courtesans, at a dinner party—are considered worse than Medusas. Even today, it's a common trope to portray female politicians as the monster Medusa.

Clockwise from left: Gianni Versace (Italian, 1946–1997). Design House: Gianni Versace (Italian, founded 1978). Dress, fall/winter 1992–93. Wool/silk blend, leather, metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Barbara Rochelle Kaplan, 2004 (2004.65.1). Dress (detail). Brooch, before 1888. Firm of Castellani; mosaic possibly by Luigi Podio. Italian. Glass micromosaic, gold, 1 1/2 x 2 1/4 in. (3.8 x 7.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler, 2007 (2007.299.1)

What do you think about Gianni Versace's decision to use the Medusa as his label's symbol?

Medusa is a potent face and an excellent choice, highly recognizable and evocative. Along with Renaissance and Baroque influences, Versace often used classical motifs in his designs. I'm sure he was inspired by the beautiful Medusas he saw on Roman mosaics in his native Italy. One could say that the motif also expresses an ambivalence towards women—admiration as well as fear.

Why are the monsters beautified in the classical period?

Because they cannot escape the pull of classical humanism! In art of the fifth century B.C., the measure of all things is the human being, and humans are portrayed as ideally proportioned and harmonious. As the monsters become more human, they become more beautiful. This beautification is really an aesthetic and artistic choice, but there is also a gender dimension. The ideal of human beauty was the male body. It was the male warrior, the male athlete, who was visibly nude and seen in the palaestra and the gymnasium; the females were secluded in the house; they were not exposed. The heroic male nudes of this time display a hyper-realistic, impossibly well-developed musculature. Their idealized appearance signifies excellence—not only external beauty, but also moral excellence. In this period, beauty is associated with good character, and ugliness with bad. That dimension is present with Medusa.

One could also argue that the beautification of monsters is a mode of control. Beauty is a form of controlling women that persists today. Take the booming beauty industry. Medusa is a common motif in decorative arts, even today. The monster becomes an ornament.

In fact, all of these monsters are still with us. They have a grip on our imagination. I once gave a tour in the galleries, and a six-year-old boy knew a lot about Medusa. Even the words we use go back to antiquity. Take the word "siren."

Terracotta stemless kylix (drinking cup), late 4th century B.C. Attributed to the Asteas Workshop. Greek (South Italian, Paestan), Classical. Terracotta; applied color, overall: 2 x 7 3/4 in. (5 x 19.5 cm); diameter of bowl 5 1/8 in. (13 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Rogers Fund, 1989 (1989.11.12)

Modern sirens make a terrible noise. Wasn't the song of the ancient sirens very beautiful? It was the ultimate music. That's why Odysseus really wanted to hear it.

But their song was a trap! The sirens are not like Medusa, where there's instant death. Homer says that when sailors hear the sirens' sweet song, they are mesmerized. They die because they are so enthralled that they can't eat or sleep. Have you noticed that in the Odyssey Homer mentions the name, but not the appearance, of the sirens? He doesn't talk about them as birds with human faces; he only shows us what they do to seafaring men. He depicts their deadly power indirectly, telling us that they are sitting on a heap of bones with rotting flesh. Their song is a warning.

Terracotta kylix (drinking cup) (detail), early 5th century B.C. Greek (Boeotian), Classical. Terracotta; black-figure, 3 1/8 x 12in. (8 x 30.5cm); diameter 9 3/8 in. (23.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Ernest Brummer, 1957 (57.12.5)

Would the ancient Greeks who heard the Odyssey recited have seen representations of the sirens? Would they have been able to visualize them as they listened to the story?

Yes! Sirens were portrayed as hybrid creatures with a human head and the body and claws of a bird of prey, and appeared on funerary monuments and bronze or terracotta vessels and implements. The iconographic motif of the bird with the human face comes from the Near East and Egypt.

In early archaic Greek art we see the siren as a bird with a human face, but as time goes on, the sirens get more and more human and feminine. In the late archaic period they are portrayed as female musicians. They develop arms, which are essential to play music. There's a cup in the show that depicts the sirens playing instruments [above].

Later, in medieval times, artists started to depict them as mermaids, and both iconographic types co-existed, the bird and the mermaid.

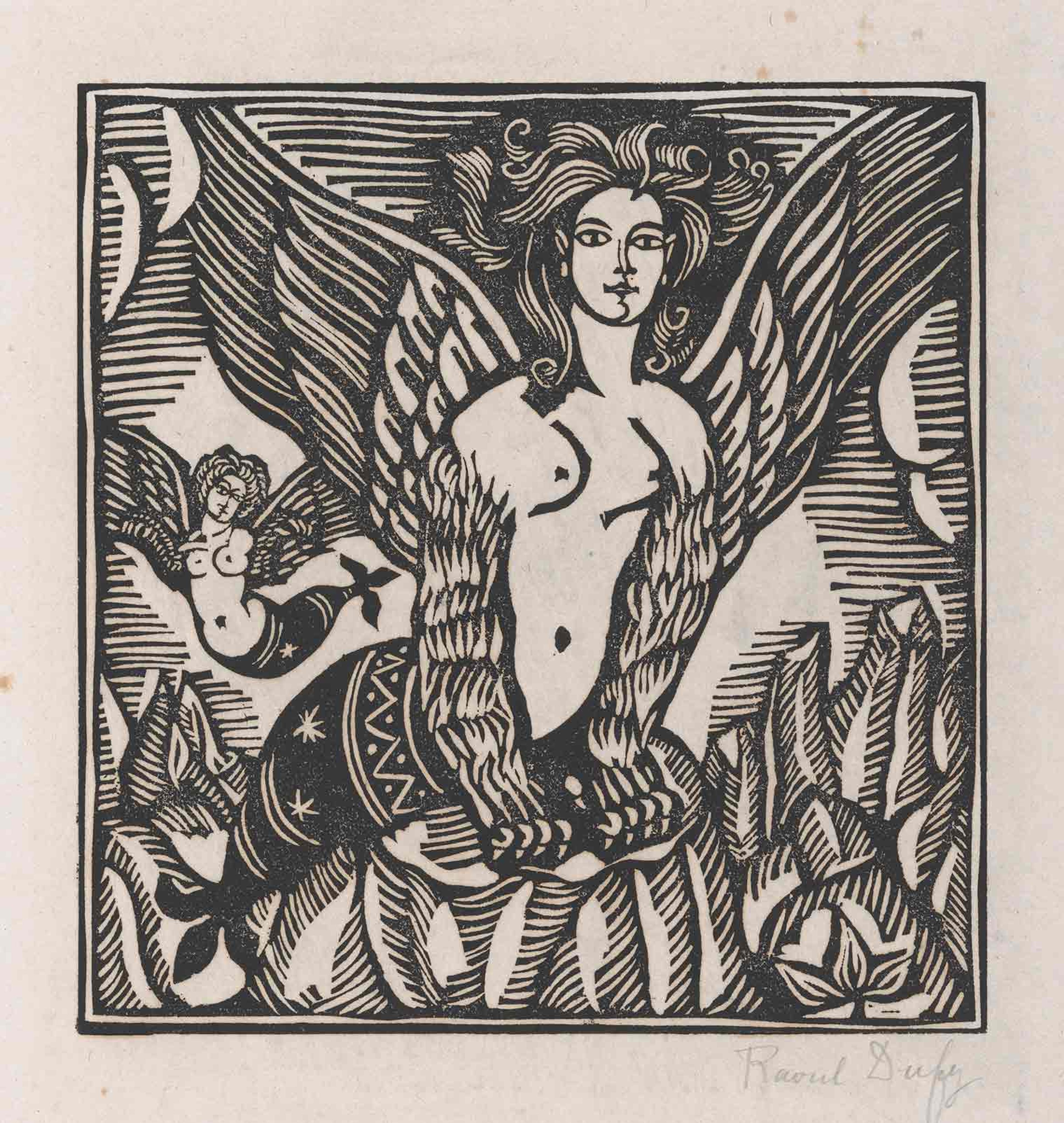

Raoul Dufy (French, 1877–1953). Sirens (Les Sirenes), 1910. Woodcut, block: 8 x 7 5/8 in. (20.2 x 19.4 cm); sheet: 11 5/8 x 14 7/8 in. (29.3 x 37.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1926 (26.92.1). © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Today, of course, sirens are always shown as mermaids, as in this print by Dufy [above]. It's interesting, the Dufy. The artist combines the ancient Greek bird-woman with a mermaid and adds an element from his own imagination—she has a bear's forelegs instead of arms! Dufy's siren is an ultra-hybrid.

Terracotta stand with sphinx, ca. 520 B.C. Greek (Attic), Archaic. Terracotta; red-figure, H. 10 1/4 in. (26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Norbert Schimmel, 1980 (1980.537)

The sirens destroy men with their song. The sphinx traps them with a different verbal device, a riddle.

The riddle itself is not unique; it's present in many cultures. What's unique in the Greek myth is that the riddle is delivered by a female sphinx.

The sphinx is a wise figure sent to Thebes as divine punishment for an unsolved murder. Sitting on a mountain and chanting a riddle, she devoured anyone who gave the wrong answer. In Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, the sphinx is ultimately defeated by Oedipus's superior male intellect, although solving the riddle also sets in motion his downfall.

That's what gets picked up in the nineteenth century.

Left: Claude-Ferdinand Gaillard (French, 1834–1887). Oedipus and the Sphinx, after Ingres. Etching on heavy wove paper, sheet: 19 3/8 x 12 3/8 in. (49 x 31.5 cm); plate: 10 1/8 x 7 1/8 in. (25.6 x 18 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Phyllis Massar, 2011 (2012.136.485). Right: Gustave Moreau (French, 1826–1898). Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864. Oil on canvas, 81 1/4 x 41 1/4 in. (206.4 x 104.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of William H. Herriman, 1920 (21.134.1)

There's a print by Gaillard in the exhibition [above left] that reproduces Ingres's famous painting Oedipus and the Sphinx in the Louvre. In the print we see Oedipus solving the riddle. Many men have tried before him and perished, as you can tell from their bodies piling up at the bottom!

In a another gallery at The Met, you can see the namesake painting by Moreau, where the Oedipus episode is highly eroticized [above right].

In the publication that accompanies the exhibition, one page is devoted to a modern sphinx. What do you make of Kara Walker's Sugar Baby?

I like the way she has transformed the image of the sphinx, showing how it can be used in a totally different context and still be very powerful. Walker's statue, if you saw it, was colossal. It was a monument; it reminded one of the Sphinx of Giza. She transformed the iconography completely. The white, sugar-coated sculpture is a powerful political and racially charged symbol of the painful legacy of the sugar and slave trade. It conveys the struggles of black American women in particular.

Kara Walker (American, 1969–). A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, 2014. Polystyrene foam, sugar, approx. 35.5 x 26 x 75.5 feet (10.8 x 7.9 x 23 m). Installation view: Domino Sugar Refinery, A project of Creative Time, Brooklyn, NY, 2014. Photo: Jason Wyche, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. Artwork © Kara Walker

Her monumental sphinx is housed in a sugar factory. She appears powerful, and yet she's caged. Her labor fuels the very system that enslaves her.

A sphinx made of sugar is ephemeral, vulnerable. In a reversal of roles with the Theban sphinx, Walker's sphinx is the recipient of brutality. When it was exhibited, you could actually see her enlarged vulva, perhaps an allusion to rape and sexual abuse. Only the left hand that makes the figa gesture was preserved. It was exhibited in 2017 at the DESTE Foundation Project Space, Slaughterhouse, on the Greek island of Hydra. The figure of the sphinx continues to be used to convey different messages and is always so relevant. The allegorical resonance is still there, and it works.

Hélène Cixous used the Medusa as a metaphor for the power of women's speech. Observing how women are routinely silenced, she says that we learn to regard our own speech as monstrous, and that in this silencing, "we are all black, and we're all Africa." We saw this last year when Elizabeth Warren tried to read aloud the letter from Coretta Scott King in the Senate.

The scenario of silencing strong women has been rehearsed since antiquity. Already in the Odyssey, Telemachus silences his mother, Penelope, as his coming-of-age moment. So yes, feminists like Cixous have tried to adopt Medusa as a symbol of female empowerment. At the same time, the image of Medusa is widely used as a misogynistic tool to malign female politicians.

As Mary Beard discusses in her recent book, Women & Power: A Manifesto, during the heated 2016 presidential election Trump's campaign appropriated Cellini's famous bronze sculpture Perseus with the Head of Medusa. Donald Trump poses as the hero Perseus with the decapitated Medusa head of Hillary Clinton. In another instance, Angela Merkel's face is superimposed on Caravaggio's shield.

The show is very timely in this age of #MeToo.

I'm surprised that only a couple of reviewers picked that up! The women who have been victimized and silenced are speaking. The fascinating thing about the myth is that it can be used in so many different ways. Even though Medusa is dead, she is still powerful. Her head is still a weapon.

Left: Plaster cast of head of Medusa, after Canova, 1806–7. Studio of Antonio Canova (Italian, 1757–1822). Italy, Rome. Plaster cast, with modern metal rod, H: 12 1/4 in. (31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1967 (67.110.2). Right: Cameo with head of Medusa, ca. 1860–70. Italy, Rome. Onyx, 1 7/8 x 1 1/2 in. (4.8 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Milton Weil Collection, 1940 (40.20.52)

What inspired you to do an exhibition on composite creatures? What have you enjoyed most?

I was creating a video feature on the sphinx, and I suddenly realized that most of these creatures are female. I had known that before, of course, but it struck me in a different way. So I went to Carlos Picón, then curator in charge of Greek and Roman Art, and asked him if I could do the show. He said yes, and he put an interesting limitation on it: "We'll do it as an in-house exhibition, no external loans." That turned out to be a rewarding challenge, because I had to "excavate" the Museum collection to find out what was here!

When I visited the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, I found objects in their storerooms that were not on display, like the plaster cast of the head of Medusa from the Canova statue [above left], and an onyx cameo with a superb head of Medusa cut in white on black [above right]. Drawings and Prints helped me find other representations. It was lovely to go in to other departments and discuss the exhibition with my colleagues and see how we could take advantage of this encyclopedic collection to do something different.

View of the exhibition gallery. Photo by Sumi Hansen

Were there any objects in The Met's Greek and Roman collection that had been overlooked and are now in the exhibition?

Yes. I've incorporated many objects from our storeroom and the Greek and Roman department's study collection. The study collection is a big space on the mezzanine, filled with glass cases overflowing with objects. So now these artworks are on display right next door, and they are presented in a different context. Instead of being lost among other objects, you can see them more clearly.

The exhibition is an otherworldly oasis in the middle of the Museum. How did you achieve that? What moments in the design and planning process were a high point for you?

The exhibition designer was Fabiana Weinberg, and we had a wonderful collaboration. As a curator, you have your checklist of objects you would ideally like to include. Most of the time, the designer's first reaction is, "Too much! You have to cut it down!" Of course, the curator always pushes back, "No, no, I want this and that." But I was open. I wanted to include the most important pieces, of course, but I was flexible about others, because we had to make choices. It was a small-budget show, so we had to use existing display cases. We were working with limitations, which is always interesting! We had these specific cases, and we could fit X number of objects according to their dimensions. We had to play around a lot.

One of the challenges we faced was that this is not a show about Medusa alone. More than half the objects depict Medusa, but it's also about Scylla, the sirens, and the sphinx. How do we create balance? My idea was to divide the room along a diagonal, so that the opening section is Medusa, and the others are farther away. Each composite creature has its own space. Fabiana accommodated my ideas to a large extent, and I also listened to her keen observations from a design point of view. For example, Fabiana suggested creating fabric-wrapped panels for mounting the prints and displaying the gallery introductory text. They look beautiful together!

The gallery is not just visual. It also has a sound experience!

I wanted to make music part of the story to add a fourth dimension to the show. Music has been played in the Museum many times as a background for the Costume Institute's exhibitions, as in Heavenly Bodies. There is also that song—"Turn to Stone." Someone actually made a YouTube video about Dangerous Beauty using that song! Of course, I would never have used that music. [laughter] That was not my idea. I wanted something different—not a familiar piece, but an instrumental soundscape that would narrate the theme in musical terms—and I preferred something original. By a happy coincidence, I was introduced to Austin Fisher in the Digital Department. He liked the concept very much. So we collaborated.

How did Austin, the composer, know what you wanted?

I'd been looking around on the web to find pieces that I liked. I’d send him samples, and he'd say yes, we can do something like that. We'd meet to talk about the show, the main ideas. Then we would listen to the music he'd written and refine it further. At one point, we were wondering how to represent the sphinx. I wanted it to be something playful, but what kind of instrument were we going to use? That was challenging. A few days later, in doing research for the Bulletin, I found out that the first usage of the word "siren" in English was for a foghorn. So I said, why don't we use a foghorn? If you listen to the music, you’ll hear it.

Composed by Austin Fisher, 2018

Are all of the monsters represented in the music?

Yes. The idea was to create themes that evoke their transformations. I think the soundscape does this well. Even when the music is serene, there's this sinister undertone. Originally, there were a lot of screeching noises, but I wanted it to be melodic too. So we altered it a bit. Austin plays it all on his synthesizer, except for one passage, the cacophonous one, where one of his friends performed live cello. It was a great collaboration. Austin did three passes, three edits, and then we had three sound tests in the gallery. We put pauses between the themes to scare people a little! When the gallery is empty, the music is audible. But when it's crowded, you really have to listen for the music. It creates an atmosphere.

So the high points for me were these very harmonious and creative collaborations.

The exhibition has been inspirational for audiences of all ages. Recently, our #MetKids team held a special children's event where the kids created video animations about composite monsters. One of the kids made a brilliant animation—

Of a Siren in the subway!

A #MetKids animation inspired by a Mermaid and the New York City subway.

You recently did a Q&A with those young animators in the gallery. Did any of their questions stand out for you?

Their focus was the sphinx. I asked them about the riddle. They enacted the riddle, but they did it backwards! They wanted to ask the sphinx the riddle, instead of the other way around.

Any ideas for your next exhibition? Will it grow out of this one, or be a complete departure?

I have other ideas. But this is also a topic we can do more with. I'm thinking about radical women, untamed women. Amazons? They've been done. Clytemnestra? Not much survives. Maenads? Everyone focuses on Dionysus, god of wine, but I don't think there's been an exhibition on maenads outside of Athens. So, an exhibition on maenads and famous radical women and outsiders. Medea was an outsider.

Curator Kiki Karoglou in the exhibition gallery. Photo by Will Fenstermaker

I have to say, Medea—and all those women you mention—had really good reasons to be radically mad.

You know, it's true! I do say that in the Bulletin too. We also have the Thracian women killing Orpheus. But do we really want to have a show about so many murders? It's kind of dark. And then we have the virgin sacrifices, where young maidens are sacrificed to the gods so that the polis, the city-state, can survive.

The ramifications are endless.

Indeed. You can start this topic and never stop.

Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through February 24, 2019

Sumi Hansen

Sumi Hansen is a senior editor on the digital content team. Before joining The Met, she was an assistant professor at UC Berkeley and copy edited for Artforum. She received her PhD in classical philology from Harvard in 2004 with a specialization in Hellenistic and Roman poetry.