Curator Conversation: Seeing the Northern Renaissance through Contemporary Eyes with Elizabeth Cleland

Associate Curator Elizabeth Cleland in Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance

«Located between The Met's hall of medieval sculpture evoking a majestic cathedral and the open atrium of early modern art is a bridge between two worlds. Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance, on view through June 23, 2019, is a pithy exhibition of 63 works dating from the 16th century and displayed on stark metal screens like those used in modern cold storage facilities, in vividly colored cases, and accompanied with labels that denote the objects' values on the 16th-century market. Visually, the exhibition marks a departure from other Renaissance exhibitions curated by the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, which often evoke a sense of place by dressing the galleries in 16th-century decor. In a sense, the intention here is reversed: rather than send viewers back in time, the objects are brought forward to today.

Intrigued by the exhibition's conceit, I met with Elizabeth Cleland, the exhibition's curator, on an early winter morning to tour the gallery and learn about the objects on display. We spoke for about an hour before the Museum opened, and as we neared the end of our discussion about the values and metrics by which a customer on the Renaissance art market might assess a work of art, the crowds began to come in.»

Will Fenstermaker: With so many European decorative-arts objects presented in such a contemporary fashion, layered with this intriguing economic system through which visitors can see how these objects were valued in the 15th and 16th centuries, Relative Values is a very experimental exhibition. How did this come together?

Elizabeth Cleland: People probably come in here and think something a bit unusual is going on. Our idea was that we wanted to get people to think beyond pigeonholes. Some people tend to say, for example, "I only like contemporary art," so we wanted to get those visitors to think about how these works were perceived when they were brand new, when they were objects of contemporary art.

Luke Syson, the chair of our department, advocates use of this gallery as a lab space. He's very encouraging that we don't just rest on our laurels with "Highlights of the Collection"-type installations, so we prepare for exhibitions in this gallery with a large amount of research, rigor, and thought. We have to have a narrative, a point, a theme, and a bit of analysis.

Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance at The Met Fifth Avenue

Michael Langley, the exhibition's designer, thought of installing the objects with these screens and displays to get away from all the clutter and paraphernalia of traditional museum installation. We wanted to try to stop people in their tracks and actually look at things. Michael has been designing shows for The Met for years and he's done a lot of shows in this gallery, so he knows how to attract visitors' attention.

Will Fenstermaker: So you really wanted to get people to look at objects again in order to challenge their notions. There are a lot of objects in the show that have been in storage, un-exhibited, for some time. Was this is an opportunity to present them in new light?

Elizabeth Cleland: Yes, definitely. The need to do a show on northern Renaissance decorative arts was rather thrust upon us because the main gallery, gallery 520 next door, is closed while the British decorative arts galleries are renovated, which is very exciting. But that meant we didn't have any northern Renaissance decorative arts out on view. My colleague Wolfram Koeppe, who is also responsible for a lot of this material, and I—I'm responsible for tapestries and glass—felt we needed to address that void. But then Luke said, "Okay, but you have to come up with a theme."

The curatorial process was very collaborative. Arms and Armor lent the bolt box, and the woodcut block is from Drawings and Prints. The painting, of course, is loaned by European Paintings. It was just fantastic of them. A lot of the objects from our department's collection are treasures one would normally see in northern Renaissance, the high-end objects—

Will Fenstermaker: The table clock, the gilded stag, the celestial globe—

Elizabeth Cleland: The jewelry, nautilus cup, those types of objects—Luke really pushed me and said, "If you're going to talk about this hierarchy of worth business, then you have to show the low-end objects, too."

Gerhard Emmoser (German, 1556–84). Celestial globe with clockwork, 1579. Austrian, Vienna. Partially gilded silver, gilded brass, brass, steel, 10 3/4 x 8 x 7 1/2 in. (27.3 x 20.3 x 19.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.636)

Will Fenstermaker: You need to have both to be able to see the scale.

Elizabeth Cleland: That was quite tricky because these are our department's treasures. We know a lot about them and they're in great condition. They're ready to display. I had to go back into the storeroom to try and find low-end objects. Things like the bottoms-up cup, which is one of my favorites.

Will Fenstermaker: Mine, too. The dripping glaze is mundane but just so charming.

Left: Bottoms-up cup or stirrup cup (Sturzbecher), ca. 1550–70. German, Cologne. Salt-glazed stoneware, 15 1/16 in. (38.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of R. Thornton Wilson, in memory of Florence Ellsworth Wilson, 1954 (54.147.60)

Elizabeth Cleland: Its use of color is very artistic; it's just that when it was made, it was at the lower, cheaper end of the market. And it's never been out on view. A lot of the glass hasn't been out for decades, which I think is really telling about hierarchies of worth within museum policies and what's traditionally been considered "worthy" of coming out to display and what is "unworthy," you know. You've got a sort of hierarchy in the gallery.

Will Fenstermaker: But here you're embracing that hierarchy in a literal way, as if to provoke the realization that this has always been the case to some degree.

Elizabeth Cleland: Indeed, we're trying to get people to understand the lens through which 16th-century people would have been looking at these objects. The aim of gallery 520 was very much to show this embarrassment of riches. You'd go in and you were just assaulted by this gleam of gold. We had tapestries on the walls to give people a sense of this sumptuous material splendor.

Gallery 520, pictured in 2011, before closure for renovations of the British decorative arts galleries.

The drawback of that was that unless you were particularly interested in the period, you might not stop and look at each object individually. Here, with Michael's design, which isolates each object, we want to catch that whole extra audience who might normally not pause in front of this type of object.

Will Fenstermaker: Even though they're displayed individually, a lot of objects complement each other. Like the clock and the hourglass. One of my favorite juxtapositions is Diana and the Stag and the clay puzzle bottle, both of which were used to play drinking games. The gilded stag is one of the most expensive items, and the puzzle bottle is one of the least, but the games they were used to play are similar.

Left: Puzzle bottle, 16th–17th century. French. Lead-glazed earthenware, 10 x 9 in. (25.4 x 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.194.2213). Right: Joachim Friess (ca. 1579–1620). Diana and the Stag, ca. 1620. German, Augsburg. Partially gilded silver, enamel, jewels, 14 3/4 x 9 1/2 in. (37.5 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.416)

Elizabeth Cleland: That's one of the fun things with really trying to take ourselves back to the 16th century. Whatever social or economic class, people got drunk and had fun. It's a reminder that although there are lots of differences with our lives today, there are a few parallels, too.

Will Fenstermaker: There are a number of instances like that, where you get the sense that the material and other things might differ across objects, but the purpose, the utility, or the desire for these objects is really universal across different areas of the northern Renaissance, or even across time into today.

Elizabeth Cleland: Across the board, people value utility and recreation. They want useful objects, and if they can be embellished as works of art, all the better.

Will Fenstermaker: Like the game board in the exhibition. It's so elaborate.

Elizabeth Cleland: The design is based on an Italian print but the game was played throughout Europe, and this board was made in India.

Will Fenstermaker: With South Asian materials? It must have been considered very exotic in Europe at the time.

Chess and goose game board (detail), late 16th century. India, Gujarat. Ebony, ebonized wood, ivory, horn, gold wire, 16 1/2 x 16 15/16 x 1 1/8 in. (41.9 x 43 x 2.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Pfeiffer Fund, 1962 (62.14)

Elizabeth Cleland: In several senses, yes. Some of the numerals, like the "4" on the side, are really old-fashioned by that date. The design is based on a woodcut that was made considerably earlier and the artisans were just copying it.

Will Fenstermaker: So they wouldn't have known the numeral was an anachronism. Would the collector have appreciated it?

Elizabeth Cleland: Oh, that's one of those unknowns! The pleasure of this exhibition is that once we've laid the ground rules between intrinsic and extrinsic values, then you can start to ask, "But what about reaction?" Did it annoy them? Or did they not even register that was an old-fashioned "4"?

We're really just scraping the surface of what was around at the time. The silverwork and that sort of portable wealth—there would have been so much of that, but a lot was melted down, except for what was cached away in a hidey-hole and only discovered in the 19th century.

Left: Probably Abraham Riederar, the Elder (German, ca. 1546/7–1625). Tankard, ca. 1580–85. German, Augsburg. Gilded silver, 4 in. (10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1911 (11.93.16). Right: Probably Simon Pissinger (active 1582–1609). Two double standing cups (trussing cups), ca. 1600. German, Regensburg. Gilded silver, 11 5/8 in. (29.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1911 (11.93.15a, b)

Will Fenstermaker: The Augsburg gilded silver tankard and double cup are notable in that regard. It's rare that valuable silver objects like these weren't melted down.

Elizabeth Cleland: Those objects are from around the time of the 30 Years' War. The owner thought he would get back to retrieve his wealth. Poor chap obviously never did.

Or the bronze monkeys: these are really unusual survivals of monumental-scale architectural arrangements. We know there were quite a few of such fountains and things because they're described in the documents, but most were melted down. Happily, someone recognized that these monkeys were creative works of art in their own right. Wolfram Koeppe acquired the monkey on the left in 2016 and the other is a loan. Wolfram posits that they're probably part of a fountain arrangement.

Left: Possibly Caspar Gras (Austrian, 1585–1674). Monkey fountain figure, ca. 1600. Austrian. Bronze, 13 1/8 x 7 11/16 x 10 1/8 in. (33.3 x 19.5 x 25.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Acquisitions Fund, 2016 (2016.375). Right: Possibly Caspar Gras (Austrian, 1585–1674). Monkey, ca. 1600. Austrian. Bronze, 13 9/16 x 7 5/8 x 9 7/8 in. (34.4 x 19.4 x 25.1 cm). On loan from Mrs. Judith M. Taubman, 2017 (L.2017.35a, b)

Will Fenstermaker: They've got these funny gaps in their hands, as if they were holding something.

Elizabeth Cleland: Probably a railing around a fountain-type object. Or maybe—I really love this idea—they were holding whirligigs that would spin as they caught the water of the fountain, like a child's windmill on the beach. Wouldn't that be fantastic?

Will Fenstermaker: I like that idea because it explains why their faces are so joyous.

Elizabeth Cleland: The artist, probably Caspar Gras, used one model during the production process, but amended each cast slightly. They have unique, tiny details, especially in their faces.

Will Fenstermaker: When objects like this were melted down and sold for raw materials, would that bronze have been used to make another sculpture by another artist, or . . . ?

Elizabeth Cleland: That would be a lovely idea. I fear a lot of it was used for weaponry—cannons and such.

Will Fenstermaker: I didn't want that to be the answer.

Right: Hubert Gerhard (Netherlandish, 1540/50–1621). Pietà, after 1595. Bronze, 11 5/8 x 6 1/2 x 7 1/2 in. (29.5 x 16.5 x 19.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Anthony and Lois Blumka, 2013 (2013.966)

Elizabeth Cleland: Well, this bronze Pietà is interesting in that regard because if you look at the Virgin's hand holding Christ's shoulder, you'll see it actually failed during the casting process. When you think of how expensive this raw material is, normally they would just melt that down because the cast is ruined, but in this instance, they opted to keep it anyway. With this particular process, once you've used that work's mold, you've lost it. It's a one-off opportunity.

Will Fenstermaker: It's not as if they could melt it down and try again. That's just what they got. So not only is it rare this has survived because it's bronze, but it's even rarer that it survived as a defective object.

Elizabeth Cleland: Hubert Gerhard was an esteemed artist and it's such a beautiful object except for that hand. You can imagine the swearing when it came out of the mold. It probably could have been worth three times as much.

Will Fenstermaker: I was struck by the story about Albrecht V told on one of the object labels. You wrote that he claimed to spend, every year, the equivalent of 1,000 years of soldiers' wages on art. What were the reasons that nobility had for collecting such a vast wealth of objects?

Elizabeth Cleland: In the 15th century, the medieval period, portable wealth reflected the prestige and esteem of the ruler. Once we get into the 16th century, we start to see an interest in curiosity cabinets, which would come to be called Kunstkammern. These collections reflected wealth, yes, but also the intellect of the owner and the breadth of the owner's power—their territories, their reach, their pull. Even if the ruler didn't actually have territories spreading into the east, they could show they had the wealth and logistics to be able to acquire these objects.

Will Fenstermaker: Another story in this exhibition that intrigues me is about Isabella the Catholic. She spent more money acquiring 12 miniature tapestries than she paid for a decade's-worth of wages for the shipmaster on Christopher Columbus's transatlantic journey. To me, this illuminated just how valuable and prestigious collecting art was back then. It suggests just how powerful these objects were at the time—I mean, this was the age of exploration, and yet Isabella considered her tapestries more valuable than one of history's most famous voyages.

Elizabeth Cleland: Yes, Isabella the Catholic, or Isabella I of Castile, was one of these southern European collectors who really prized northern European artistic plush, especially tapestries. This is one of those great instances where we have a lot of surviving archival information, so we can piece together what happened. She had agents whom she sent up to Flanders on buying trips. They would go to fairs and dealers, buying the sorts of objects they thought she would like. Sometimes there was a back-and-forth dialogue with Isabella, but it seems that her agents were often just buying these smaller-scale devotional tapestries she liked.

Will Fenstermaker: So the story about Isabella is different from the story about Albrecht V in that it's less about the wealth of the empire and more about the traditions of tapestry weaving.

Elizabeth Cleland: Nobles have been collecting tapestries since at least the late 14th century, so this is still very much a continuation of the medieval mindset. With tapestries, there's a more established tradition than with objects of exotic materials intended to display the wealth of the empire or the power of the ruler.

Will Fenstermaker: Tell me about the reasons tapestries were so prestigious throughout the centuries.

Elizabeth Cleland: The first and most fundamental is that they served as portable insulation for cold, drafty palaces. In the 14th, 15th, and early 16th centuries, it was very unusual for the court to stay in just one palace. We know from account records that Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, paid carters to travel ahead of the court and dress the empty palace with tapestries before they arrived. Also, because they weren't for permanent display, tapestries tended to be kept rolled up in stores, which is partly why the ones that have survived in their original collections—like former Habsburg holdings now in Madrid and Vienna—are often in such good condition.

Tapestries have this prestige of being an art form that only the wealthiest ranks of nobility could afford. This was partly to do with the intrinsic value of the raw materials—wool, silk, and things like that were expensive. But the small-scale devotional tapestries that Isabella really liked also have lots of precious metal-wrapped thread, which is literally a silk core wrapped with very, very thin strips of silver.

Left: This 16th-century illustration depicts weavers (at left) working alongside painters (at right). Chapter XLVIII: "De Textoribus, & Pictoribus," in Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (A Description of the Northern Peoples) (Rome, 1555). Image via Project Runeberg

There's also the virtuosity and prestige of the highly trained professionals making these. It takes months to weave a tapestry, so there are obviously expenses involved in that. There's not just the tapestry itself, there's also paying for the design from a petit patron drawing, and paying for the full-sized, painted cartoon that the weavers copy.

Lastly, there's logistics. With Isabella of Castile, they weren't weaving tapestries like this down in Spain. We have a few documented cases of Flemish weavers who moved down to southern Europe to set up small workshops because they were aware of the market, but this sort of thing was really done in Brussels. The best weaving centers were in Flanders, so you had to pay to have these objects transported all the way down to Spain.

The other point to bear in mind is that this is just a door tapestry. In 16th-century terms, this is tiny! Most tapestries were massive.Normally, a wall hanging would be about six to eight times the size of this tapestry. The valuation on the exhibition label was worked out by the price per ell, which is a unit of measurement from inventories. Basically, you have to multiply this by six or eight to get to the price of just one wall tapestry. By the early 16th century, it was quite unusual to have just one stand-alone wall tapestry commissioned. Usually they were designed and made in sets telling a whole narrative or allegorical story. You might have five, six, seven, even up to 10 wall tapestries in one set. That's when you start to realize, looking at the equivalence in salaries and things, that these really were inconceivably expensive.

Will Fenstermaker: This is symbolic of the kind of wealth only a Renaissance queen could accumulate.

Possibly after a design by Bernard von Orley (Netherlandish, 1492–1541/42). Saint Veronica (detail), ca. 1525. Wool, silk, gilded silver metal-wrapped threads, 68 x 51 in. (172.7 x 129.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.190.80)

Elizabeth Cleland: Yes, and then you're getting into the self-perpetuating appeal of such a status symbol.

Will Fenstermaker: I see—to an extent, tapestries are valuable because they are tapestries, however odd that sounds. But they do have a utilitarian function, because they're warming, and they have cultural value as well. And, of course, they're made of very expensive materials by expert artisans.

Elizabeth Cleland: Yes, and it's a really beautiful medium. I think that's another thing we tend to forget because even something like this, you know, the silvers have tarnished, the colors have faded—

Will Fenstermaker: This must have once been glowing.

Elizabeth Cleland: It would have glittered in the candlelight, which would have been incredible. Looking at contemporary accounts, you see that what they liked about tapestries is their physical sumptuousness. They bring color and texture to the wall.

This is just a door tapestry, but imagine a wall tapestry playing with space like this. Here you've got three spatial planes. First, you've got the landscape, which, as in panel painting designed by this date, is punching a hole in the wall. Then you've got the border, which is on the same plane as the wall. And then in this instance you have the figure actually stepping out as if she's coming into our space.

If you imagine a whole wall playing like this, it gets really fun with what's real, what's represented. Think of a set of six monumental wall hangings, literally hanging so they abut each other from floor to ceiling, enveloping the palace hall and creating this whole fictive space within the actual space.

Right: Follower of Quentin Metsys (Netherlandish, mid-16th century). The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, ca. 1540. Oil on wood, 37 1/2 x 30 1/4 in. (95.3 x 76.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931 (32.100.52)

Will Fenstermaker: I understand painters would design tapestries because of their higher valuation on the market. Was there a lot of collaboration in that regard?

Elizabeth Cleland: Oh, absolutely yes. What we really don't want to do with this exhibition is suggest that these objects are competing, or that one object is in any way this nasty, cheap knock-off of higher-valued objects. It's more complex than that. And when you look at contemporary accounts in which people describe why they liked something, there are qualities ascribed to panel paintings that sculpture and tapestry just can't compete with, such as this idea of life-likeness, where the flesh looks so alive.

Will Fenstermaker: A tapestry can't layer color in the way oil paint can, but it's not a dichotomy, as if they're against each other.

Elizabeth Cleland: In fact, what we find is that any artist who's worth their salt in the late 15th and early 16th centuries in Flanders, they'd be doing panel paintings as well as designing tapestries, because that's where the prestige lies. So for example, I curated a show back in 2014, Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry. Coecke was an example of a highly admired artist who could paint fantastic panel paintings, but he actually chose to spend most of his time designing tapestries. What was really special about him was he also used a technique of painting in tempera on cloth and paper, so with his workshop he could paint cartoons as well. He was also designing stained glass and all sorts of decorative arts. He really was a designer extraordinaire, a case in point that a prestigious artist wanted to work across media. When he was alive he was very celebrated, until 100 or so years after his death, and then he completely faded into obscurity.

Exhibition view of Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry at The Met Fifth Avenue

Will Fenstermaker: So Coecke was an end-to-end designer of these works, but because we value painting today and that wasn't his primary output, he's been somewhat forgotten. It's an interesting aftermath of paragone, this idea that one art form is superior to others.

Elizabeth Cleland: Yes, and that raises a whole set of implications that we couldn't even hope to address in the context of this show. There's no acknowledgement on a tapestry of the name of a designer. By this period, on wall tapestries we often see a weaver's mark as an acknowledgement of the weaving workshop. But even then it's not a legible name; it's just a little geometric mark. So the people who counted—the consumers like Charles V, Isabella the Catholic, and so forth—even if they noticed the mark, they certainly wouldn't know who that was. It's one of the reasons Coecke became so obscure.

Will Fenstermaker: It makes sense, economically, to work in the way that he did. Painting was affordable to the mercantile class, whereas tapestries of this quality were only something that royalty could afford. And if you're looking to secure patrons, you needed them to buy expensive items to fund your workshop. But without an identity, it's hard to stand the test of time.

Elizabeth Cleland: Exactly, it wasn't always about authorship. It's really only once you get into the early 17th century that you start seeing weavers put their full name, and it's only in the mid-17th century that we start seeing both the designer's and the weaver's names acknowledged on the object. That seems to have been something that, to a certain extent in some areas, they weren't all that interested in—this sort of public proclamation of their artistic role in the creation.

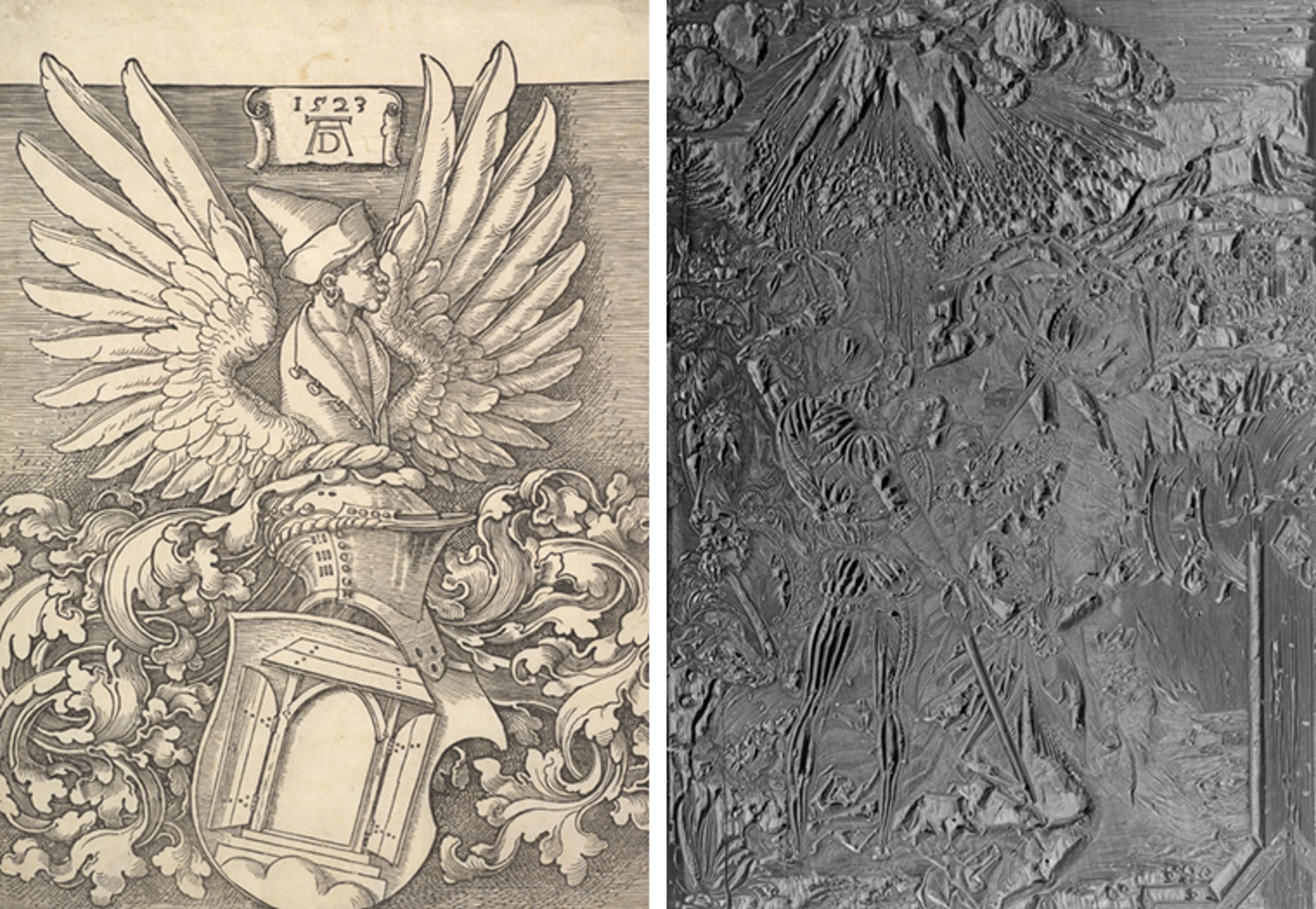

Will Fenstermaker: With that, I'm reminded of the three Dürer works in the show, because he was someone who really proclaimed his identity as an artist. I guess I should say the two Dürers and the known forgery. What was so interesting to me is that the fake Dürer was worth more than the known Dürer print.

Right: After a composition by Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528). Female Nude Seen from Behind, early 17th century. German. Honestone, 6 x 2 5/8 in. (15.2 x 6.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.467)

Elizabeth Cleland: You know, with prints, he does have his monogram on there; he was making sure he was known. That said, it's tricky because in terms of prints, he was certainly not the first person doing that; but he was proclaiming the importance of his authorship so much that it then rolled on and we start to see monograms appearing on other types of objects, like this honestone plaque, which was considered more expensive than the print when they were new.

I think this is still true today—even though engravings were already prized and collected by the big collectors of Dürer's day, who pasted them into albums, they are still multiples. There was still this slight hesitation regarding the fact that they are not unique, which was reflected substantially in the price, but not astronomically.

Of course, tapestries are multiples too, once you have a cartoon.

Will Fenstermaker: But creating an edition of a tapestry is a more intensive process than just rolling pear wood with ink and stamping it. As you said, it takes months of hard, direct labor.

Elizabeth Cleland: That's true, but maybe this idea of us prizing something that is unique is actually a more recent reaction. With tapestries, that group of 10 collectors who were wealthy enough to all own matching editions of the History of Troy, for example, were almost part of a club. With prints, it's slightly different. One of the reasons why the honestone plaque was so valuable, even though today we know it was actually made about 70 years after his death, was because it had this special notion that it was touched by Dürer's hand, as opposed to merely a print of his design.

Left: Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528). Coat of Arms of Albrecht Dürer, 1523. Woodcut, 13 13/16 x 10 1/4 in. (35.1 x 26.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1952 (52.281.1). Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528). The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, ca. 1498. Black ink on carved pear wood, 15 1/2 x 11 1/8 x 1 in. (39.4 x 28.3 x 2.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Junius Spencer Morgan, 1919 (19.73.256)

Will Fenstermaker: That's an interesting distinction—that it wasn't unique or rare, but was valued nonetheless because it was believed to come from the artist himself, almost like a signed concert ticket. It's actually the third Dürer object—the woodcut printing block—that was the most valuable Dürer in the show. Would that have been because the owner could produce editions and sell them?

Elizabeth Cleland: Exactly. In this case, it's not, as we might think, about the prestige of the artist. Nowadays, it's so exciting to realize that this could well have been cut by Dürer himself. Some prints scholars have said woodblocks could be used for thousands of impressions, so this would obviously have been a very desirable tool to have when it was new.

There are many surviving documents that talk about scenarios in which a printmaker died and then another printmaker bought up the workshop's stock. You start seeing the sorts of money involved and it certainly took me by surprise how expensive these woodblocks were.

Will Fenstermaker: It was really an investment rather than a collection.

Elizabeth Cleland: Totally. It wasn't even really collected—it was an industry.

Will Fenstermaker: The glass objects were also part of a well-established industry, right? Can you tell me a little bit about Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabee Brothers and Their Mother?

Designed and executed by Dirck Vellert (Netherlandish, ca. 1480/85–ca. 1547). Martyrdom of the Seven Maccabee Brothers and Their Mother (detail), ca. 1530–35. Flemish, Antwerp. Stained glass, 27 3/4 x 18 1/2 in. (70.5 x 47 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mr. and Mrs. Isaac D. Fletcher Collection, Bequest of Isaac D. Fletcher, 1917 (17.120.12)

Elizabeth Cleland: The stained glass is a wee bit like tapestry in that we know that artists were designing stained glass in addition to panel paintings and so forth. But this one is unusual. This is by Dirck Vellert, and he's interesting because, a bit like Coecke painting tapestry cartoons, he was a great designer who also had the technical abilities to take his drawn designs further into the production process—in this instance, to paint on glass. So he wasn't handing a design over to a specialist who would mechanically copy it onto glass. He was doing it himself. Vellert was really celebrated in his day and there are a lot of things around attributed to him, but there are very few that we actually accept today. This is one of them.

Will Fenstermaker: I find the collage element and the selective use of color so modern. This has probably faded from how it would've appeared, no?

Elizabeth Cleland: No, that's the nice thing with glass—it doesn't fade. The grisaille, or gray tones, are all intentional. He really intended to have that strong shift in palette, as in that incredible crimson sleeve. And then he used green very subtly in the rest of the landscape.

Glass is very apropos to this idea of hierarchies of value. There's a story from the 15th century that might be apocryphal, but it's been repeated for centuries so it's almost mythology at this point. According to the story, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III purposely dropped a gift of glass that Venetian authorities gave him because he felt it was such a cheap material. It was insulting.

Will Fenstermaker: And glass is cheap, at least in terms of raw materials. It's just vitrified sand or similar. But it has all of these amazing chemical properties.

Elizabeth Cleland: Exactly. It was only a hundred years later that people in the north woke up and saw how incredible it is that humans, through scientific process, can take these cheap, ugly raw materials and manipulate them into incredible forms. Rock crystal, by contrast, is prized because it's solid, hard, and can still glisten after being carved. Glass can achieve similar effects, but glass blowers can manipulate the material so much more than you ever could with rock crystal. It's about form and surface decoration.

By the late 16th century, they were actually luring the Venetian glassmakers away from Murano and setting them up in little workshops of their own. There was prestige to bringing glassblowers over. Many of these objects were adapting a southern form for a northern market.

Left: Goblet (Roemer), 1608. German, Rhineland. Glass, cold-painted, gilded, 9 1/4 x 6 in. (23.5 x 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Munsey Fund, 1927 (27.185.236). Right: Bird, ca. 1580, with later renovation. German, Nuremberg. Rock crystal, with gilded silver and rubies, 12 1/8 in. (30.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.534a, b)

This here, though, is a traditional Dutch or German goblet. Those notches in the bottom are called prunts and by this date were really a decorative element. When they first originated they were there to stop people from dropping the thing.

Will Fenstermaker: I can see why that would be necessary given how valuable it was.

Elizabeth Cleland: We have documentary accounts of the frustration when shipments of glass arrived up in the north from Venice and half of them are broken!

Will Fenstermaker: That's so funny. Of course, it's not as if they were packed in Styrofoam and shipped overnight. They were strapped to a donkey, getting rattled for hundreds of miles. Stories like that are so interesting because even though Relative Values is divided into themes like "technology," "fame," "raw materials," and "paragone," there are also moments where I get the sense that there are other value systems that aren't so easy to classify. For example, the pilgrim's badges were believed to carry the magic of the saint. Or there's the belief that silver held the properties of the moon. Were these magical properties considered part of the value of an object?

Elizabeth Cleland: When I first thought of the title, it was alluding to the fact that there's more to these objects than how much they cost. In the end, having done all that research, we decided to prioritize the hierarchy of monetary worth for the original, contemporaneous audience as a gateway into reinterpreting these objects.

Left: Pilgrim's Badge with Saint Leonard, 15th century. British or French. Lead and tin alloy, 2 3/16 x 1 3/16 x 3/16 in. (5.6 x 3 x 0.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Cloisters Collection, 1986 (1986.77.1)

That said, it's not relative prices, it's relative values because things could be cherished and prized for a whole lot of different reasons, some of which are quite hard to put your finger on. Their original owners believed that these badges were radiating sanctity. In terms of talismanic power, these modest little things are the most valuable works in the whole show. Without question.

Will Fenstermaker: Right, how can you put a quantitative value on magic or religion?

Elizabeth Cleland: We have to depend on empathy. To give another example, we can see how much the gilded clock would have been worth in terms of market value, but it's such a beautiful object. I'm sure the collector who bought that would have been bowled over, looking at the beauty of the thing. But we're never going to know that unless they wrote it down, for example if they kept a diary or suchlike.

Will Fenstermaker: I'm glad you mentioned the clock, because the exhibition also notes its ability to pass its special powers to its owner. So this idea of objects being valued for their supernatural properties wasn't just in relation to religion; it also regarded technology.

Elizabeth Cleland: Yes, and that's one of the reasons why the 16th century gets so exciting. I think it's fair to say that in the 15th century, religion and the sacred use of objects was still paramount. But in the 16th century, things also develop secular dimensions. It's really the beginning of the age of discovery, and of interest and awareness of the world beyond Europe.

Movement probably by Jeremias Metzger (German, ca. 1525–ca. 1597). Astronomical table clock, 1568. German, Augsburg. Gilded brass, iron, 14 1/4 x 8 1/2 x 5 3/4 in. (36.2 x 21.6 x 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.634a–d)

Will Fenstermaker: I was stunned to learn that this clock had an alarm.

Elizabeth Cleland: I know, me too!

Will Fenstermaker: The year 1568 is centuries earlier than I would've guessed that we had that technology.

Elizabeth Cleland: It has so many different temporal functions on it. There's a whole lot of dials on the back. These really are Kunstkammern objects again; they didn't really have permanent areas of display. They're the sort of things that would've been safely kept hidden and then taken out and looked at.

Will Fenstermaker: But the owners would have believed they could magically obtain scientific knowledge, almost as if by osmosis. What would be the knowledge one could gain?

Elizabeth Cleland: Why, control of time! In this period they were still making sundials—really nice little pocket sundials, precursors of the pocket watch—but the ability to tell time accurately in this period, that's still pretty radical. People were still telling time by the phases of the moon and the tides, but alarms also mark the time, which was quite incredible to behold.

Will Fenstermaker: It's a funny reminder that commonplace knowledge to contemporary sensibilities used to be concepts that only a restricted caste of people was allowed to comprehend. And this idea is contained within the clock, which is part of why it was valued so preciously.

Elizabeth Cleland: And that's exactly the sort of things we're hoping visitors are going to see too. We want them to step away from what we think we know about these things and get back to the original viewers' reactions.

Left: Game piece with two noblemen in profile, mid-16th century. German. Boxwood, walnut, 1 7/8 in. (4.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Edward S. Harkness, 1930 (30.135.16)

My husband and I like to play backgammon, so I had this sense with the backgammon counter. We just have one counter here, but there's a whole set in the game. Here, the woods have faded, but originally the faces would have been much darker than the background. And so I suggest that the competing player's counters would have had the opposite colors.

With this level of quality, these must have been made for royalty. But thinking of them actually being used, did the players look at these counters? Were they distracted from the game—as I would be!—by their beauty?

Will Fenstermaker: Or did they have so many beautiful objects lying around that it's just another thing?

Elizabeth Cleland: Yeah, it's just a game counter to them.

Will Fenstermaker: That's just what they look like. Did they know that other people's game counters weren't that ornate? Did they possess that awareness?

Elizabeth Cleland: That's the sort of thing that unless you have a really lucky find, like a letter where someone's really pouring out their emotive, visceral reactions, we're never really going to know. Which is sort of frustrating, but I think also quite fun because it leaves some mystery to these things.

Editor's note: This interview has been condensed and edited from its original form.

Related Content

Relative Values: The Cost of Art in the Northern Renaissance, on at The Met Fifth Avenue through June 23, 2019

Learn more about systems of value in the northern Renaissance by reading Elizabeth Cleland's blog post "Counting Cows—Curating Relative Values" on Now at The Met.

Read more Curator Conversations on Now at The Met.

Will Fenstermaker

Will Fenstermaker is an editor and producer in the Digital Department at The Met.