The Final Days: Five Portraits from Leonardo to Matisse

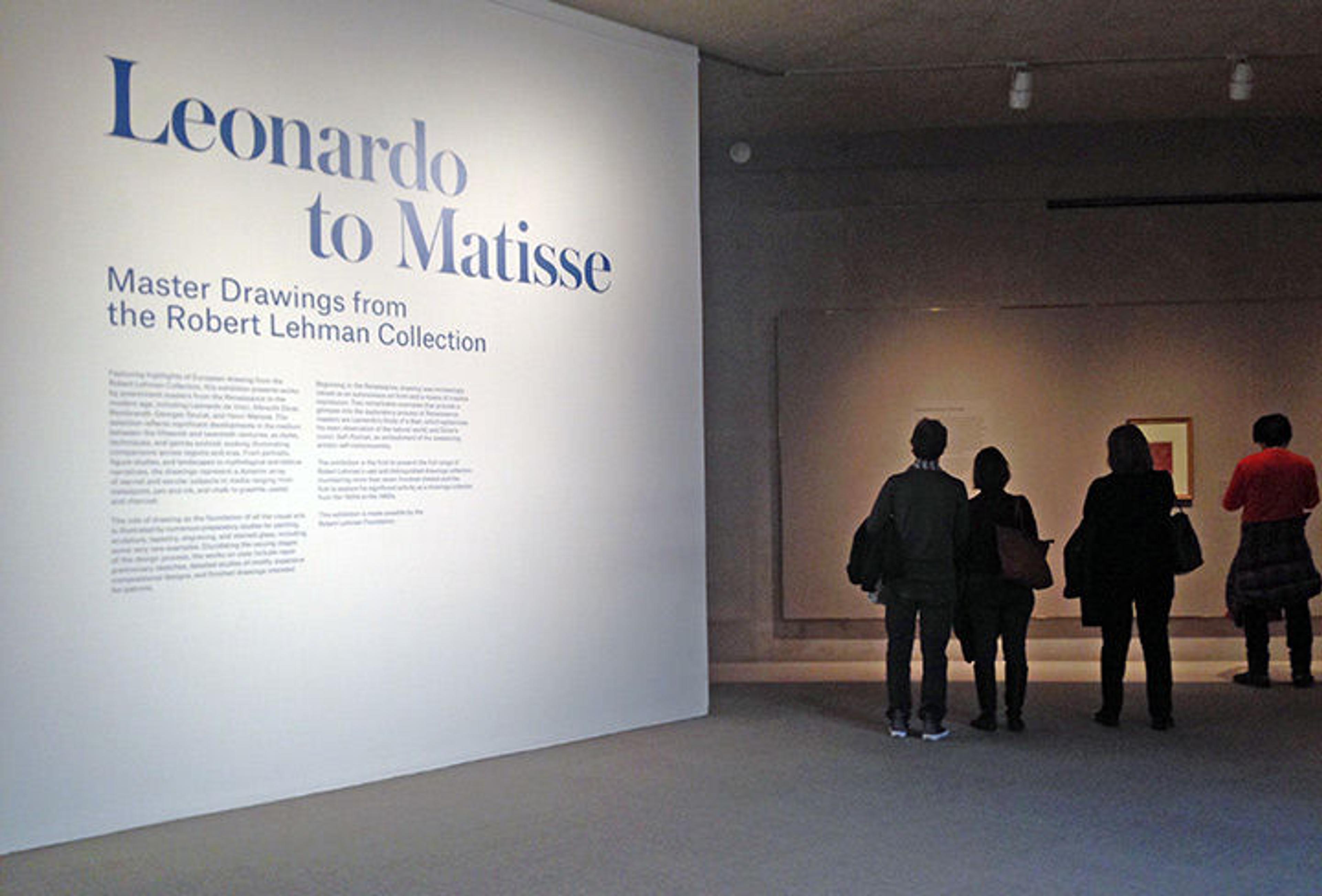

View of entrance to Leonardo to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Robert Lehman Collection, on view through January 7, 2018 in gallery 964

«In developing the exhibition Leonardo to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Robert Lehman Collection, we selected approximately 60 highlights from the 750 drawings in the Robert Lehman Collection, spanning five centuries of European draftsmanship. These drawings form part of the large and important gift of 2,700 works (including paintings, illuminated manuscripts, sculpture, textiles, and other decorative arts) that the banker/collector gave to The Met upon his death in 1969.»

The drawings on view in the exhibition illustrate developments in style, technique, and genre from the early 15th to the early 20th century by artists such as Leonardo, Dürer, Rembrandt, Tiepolo, Ingres, van Gogh, Seurat, and Matisse. The wide scope of the exhibition allows the visitor to trace a variety of drawing types and subjects through the centuries—from mythological scenes, biblical subjects, and landscapes to portraits and studies of the human form.

The portrait drawings in the exhibition are an especially significant and captivating group of works, and include some of the greatest masterpieces of the Robert Lehman Collection.

An Equestrian Portrait

Antonio Pollaiuolo (Italian, ca. 1432–1498). Study for the Equestrian Monument to Francesco Sforza, early to mid 1480s. Pen and brown ink, light and dark brown wash; outlines of the horse and rider pricked for transfer, 11 1/8 x 10 in. (28.1 x 25.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.410)

An example from the Italian Renaissance is the equestrian portrait of the Milanese duke Francesco Sforza made by Antonio Pollaiuolo, the 15th-century Florentine painter, sculptor, engraver, and goldsmith. Pollaiuolo's drawing is a very significant and rare surviving example of an equestrian portrait of the Sforza duke and records an early design for one of the most celebrated (though un-realized) bronze sculptural monuments of the Renaissance. While equestrian images of rulers abounded in the Renaissance and were inspired by examples from antiquity, the image of the armor-clad Francesco Sforza trampling an enemy upon his rearing horse while leading troops forward into battle was perfectly suited to the duke, a notorious mercenary soldier whose shrewd military skills and ruthless political maneuvering enabled him to rise to power. Francesco's facial features are highly individualized, closely resembling his effigies on contemporary coins and medals, which likely provided a model for this portrait.

The function of Pollaiuolo's drawing as a study for the so-called Sforza monument was documented by the famous 16th-century historian and artist Giorgio Vasari, who owned the Lehman Collection drawing and described it in his biography of Antonio Pollaiuolo in his 1568 Lives of the Artists. The equestrian monument was initially commissioned by Francesco's eldest son and successor, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, and was continued during the reign of another son, the despot Ludovico Sforza (best known as Leonardo da Vinci's patron at the court of Milan). Pollaiuolo may have presented this drawing to his patron in an attempt to win the prestigious commission. However, Leonardo da Vinci was selected and worked for nearly two decades, during the 1480s and 1490s, producing numerous notes and drawings for the design and casting of the horse. By 1499, Leonardo had executed a colossal clay model of the horse (three times life-size), which was destroyed during the French invasion of Milan, marking the end of the ill-fated Sforza monument.

A Self-Portrait

Leonardo da Vinci's counterpart in Northern Europe was the German Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer, who was deeply engaged in rendering his own image and was a pioneering figure in the genre of self-portraiture.

Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528). Self-Portrait, Study of a Hand and a Pillow (recto), 1493. Pen and brown ink, 11 x 8 in. (27.8 x 20.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.862)

One of the most important drawings in the Museum, Dürer's self-portrait study was made by the artist at the age of 22, reflecting his emerging self-consciousness as an artist. With its arresting directness, it is a milestone in the history of portraiture. It is one of several drawn and painted self-portraits by the artist, and likely served as a preparatory study for the celebrated self-portrait painted by Dürer in 1493, now in the Louvre. He likely used a convex mirror to record his own features. Rendered in a different scale, the adjacent study of the artist's left hand was likely made from direct observation. At the bottom of the sheet is a study of a pillow (a motif continued on the back of the sheet).

While the three studies on this page are a series of exercises, it is tempting to see an association between the image of the artist's head and hand—a connection that speaks of the combined mental and physical aspects of creativity. The hand also evokes an alternate form of self-portraiture, echoing the words of the contemporary German theologian Nicholas of Cusa: "The entire character of man is reflected in his hand." Dürer's self-portrait speaks to a much broader cultural exploration of the role of the individual in the world, as reflected by contemporary humanist thought, as well as to the rising status of the artist in society.

Three Portraits in Graphite

Inspired by Renaissance masters such as Raphael, the 19th-century French neoclassical artist Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) was an energetic portraitist both on canvas and paper. He often noted that formal portraiture left him feeling anguished, given the exacting concentration of his technique as a painter, but drawing in graphite was quite another matter. He took great personal satisfaction in his draftsmanship, amassing some 300 portrait studies in his lifetime. Ingres drew portraits as gifts for friends; he drew portraits of French compatriots while serving as a pensioner at the French Academy in Rome (1806–15); and, of course, he drew portraits as a preparation ground for magisterial commissions in oil. These studies in graphite offered a steady source of income, especially in Rome. It is said that he charged the equivalent of 30 shillings for a half-length rendering and 50 shillings for a full-length study.

The three portrait drawings in this exhibition demonstrate Ingres's exquisite mastery of line, while documenting his practice on a personal and professional level.

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867). Left: Madame Félix Gallois, 1852. Graphite with touches of gold in oil to highlight jewelry, on buff wove paper, 13 5/8 x 10 5/8 in. (34.6 x 26.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.647). Right: Dr. François Mêlier, 1849. Graphite with graphite framing lines, corrected with white, on buff wove paper, 12 3/4 x 9 3/4 in. (32.2 x 25 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.648)

Madame Félix Gallois was a cousin of the artist's second wife, Delphine Ramel. With customary ease and the controlled touch of a pencil, Ingres details his relative clothed in patrician finery. An inscription presents this sheet to the sitter's husband with affection.

The physician Francois Mélier was a distinguished physician in the field of public health. Ingres gives his sitter an air of distinction in formal contemporary attire. In addition to graphite, the drawing has a few strokes of white gouache to be observed on either side of the sitter's face. We imagine that Ingres used gouache as a corrective measure; the white of the medium is now more in evidence against the slightly discolored paper support.

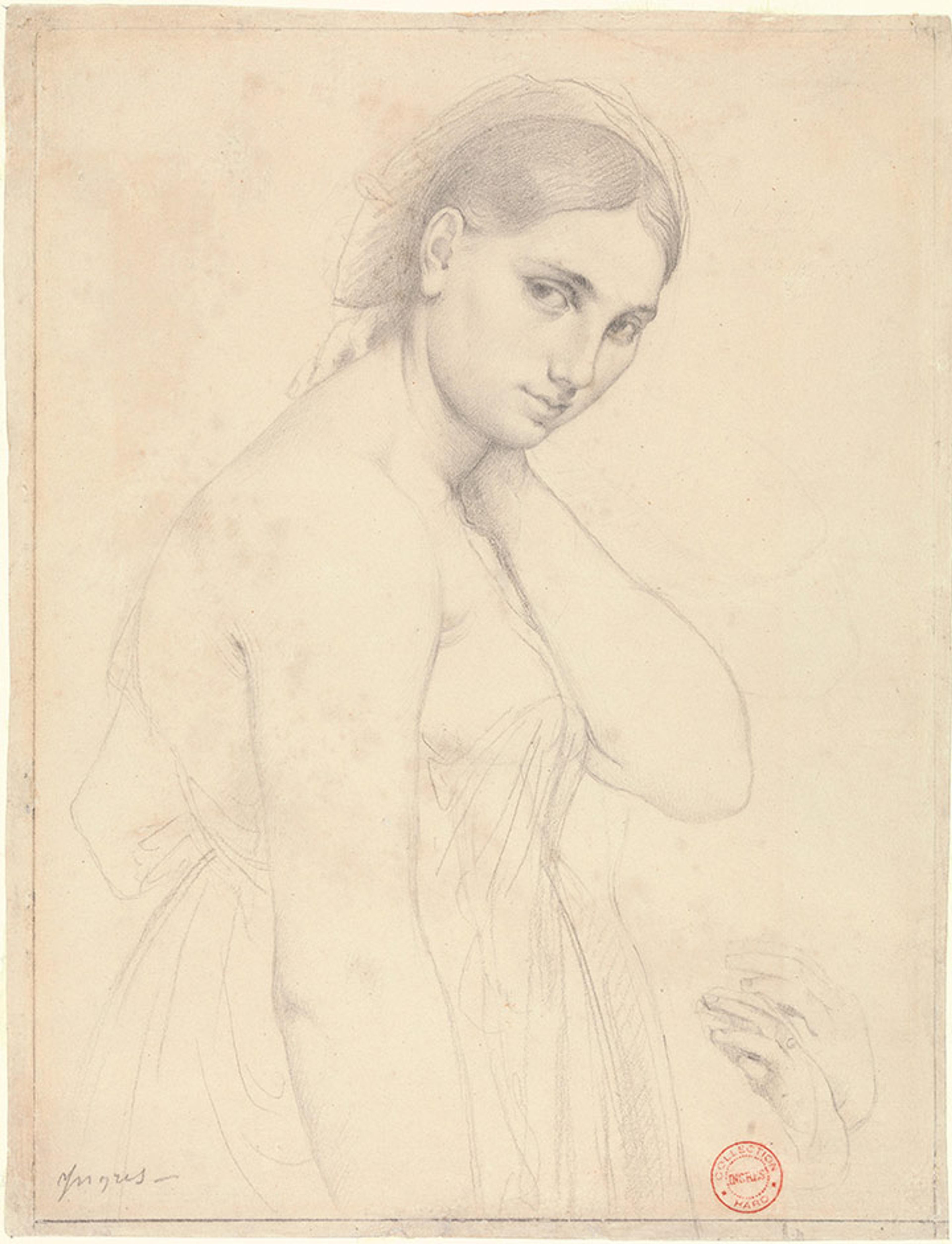

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867).Study for "Raphael and the Fornarina"(?), ca. 1814(?). Graphite on white wove paper, 10 x 7 3/4 in. (25.4 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.646)

The beguiling study for one of Ingres's many paintings of Raphael and his mistress-model, La Fornarina (the baker's daughter), is telling on many levels. First of all, it reminds us of his rigorous drawing practice. He drew hundreds of studies of his subjects prior to embarking on his paintings. That discipline dates to his training in the atelier of the great neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David. For Ingres, the discipline of drawing was the only means by which an artist advanced his skills. In this instance, an homage to the great High-Renaissance master Raphael, Ingres asked his new wife, Madeleine Chapelle, to model for him. Again, with the touch of a pencil, he has drawn a ravishing young woman. His preoccupation here is with the tilt of the head and its modelling, in addition to the placement of the left hand around the neck. Another hand study appears at lower right. The tentative expression in the drawing disappears in the painting, where La Fornarina carries a knowing self-assurance.

These five portraits are on view in the exhibition Leonardo to Matisse through January 7, 2018. Visit the online exhibition page to learn about other drawings in the exhibition.

Dita Amory

Dita Amory is curator in charge of the Robert Lehman Collection.

Alison Nogueira

Alison Manges Nogueira is associate curator of the Robert Lehman Collection.