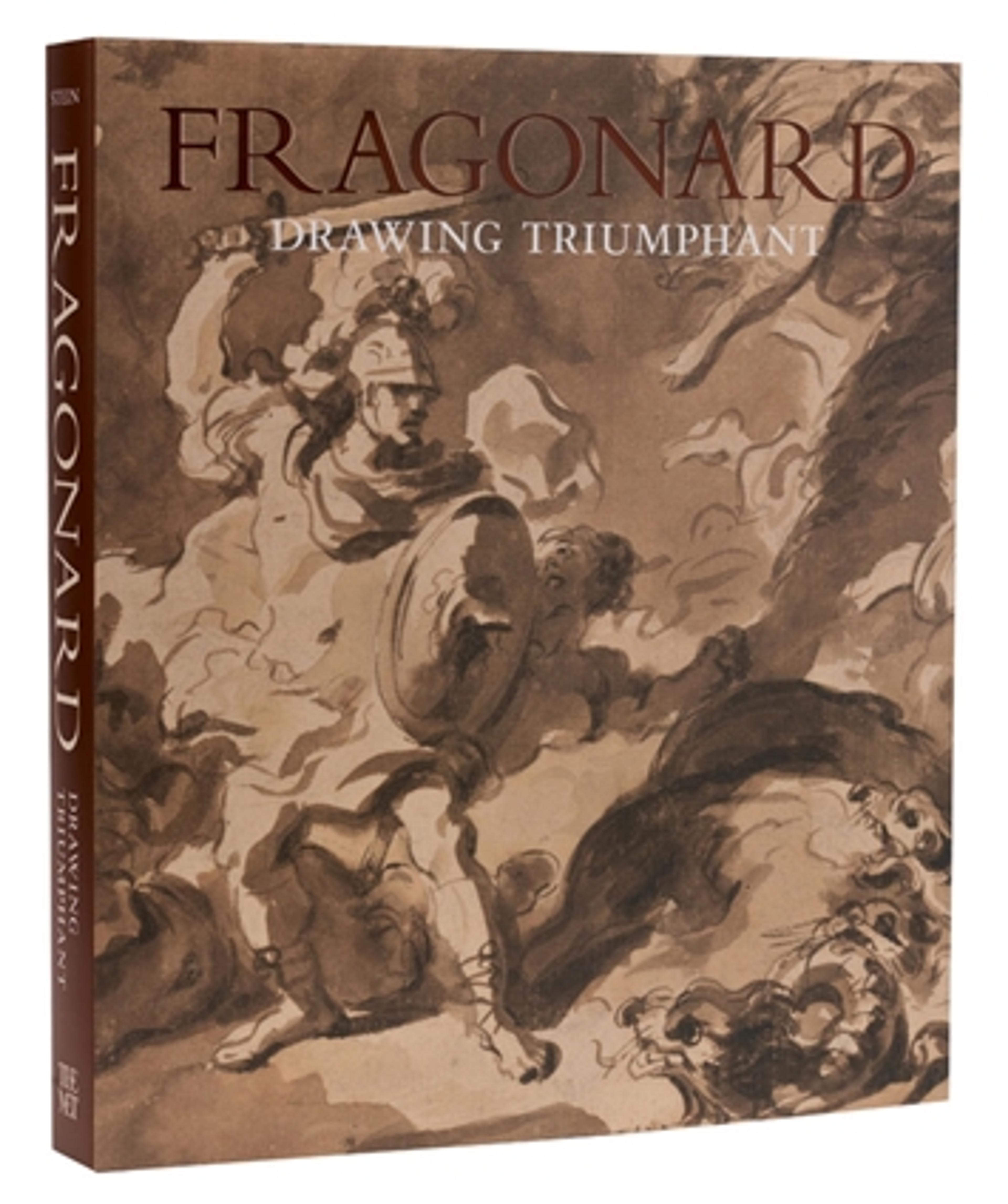

Drawn to Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant with Author Perrin Stein

«Jean Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) was a virtuoso draftsman whose works on paper count among the significant achievements of his time. Focusing on the role of drawing in Fragonard's creative process and providing a modern re-evaluation of his graphic work, Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant showcases the artist's mastery and experimentation with drawing in a range of media. The catalogue brings together well-loved masterpieces, new discoveries, and works that have been long out of the public eye, thus illuminating the career of a ceaselessly inventive artist whose draftsmanship was at the core of his remarkable body of work.»

Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant features 324 color illustrations and is available at The Met Store and on MetPublications.

I had the opportunity to speak with Perrin Stein, the book's author and the curator of the exhibition Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant—Works from New York Collections, about the "Fragonard myth," the changing role of drawing in the 18th century, and the reasons why she loves studying this artist.

Rachel High: There are several misconceptions regarding Fragonard that you cite in your text as the "Fragonard myth." What are some of those misconceptions, and how do you hope that this volume provides a different view of his work?

Perrin Stein: The "Fragonard myth," which has been gradually discredited over recent years by various art historians, has to do with reading his oeuvre through his biography, or in other words, mistaking his imagery for autobiography. There's been the assumption that his amorous scenes reflect a libertine lifestyle, and he's also been characterized, based on his upbringing in the south of France, as indolent, lazy, and pleasure seeking—all things that he depicts in his work. He wasn't read on a very deep level and his subject matter was taken at face value as being a confession of his own life. Very gradually, people have begun to put all of that aside and to look at him with modern art-historical eyes.

With this publication, I hope to shift focus away from the biography and more to the work and his working process. The contributors to the catalogue and I were all interested in the ways he left the standard path and forged a new kind of career through his friendships with collectors and with a focus on drawing. We wanted to make the point that, for Fragonard, drawings were not a preparatory step in a process, but that they were a form of artwork, and that he was part of a circle of collectors who felt the same way.

Fragonard and many of his contemporaries saw their drawings as works of art in their own right. Right: Jean Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732–1806). A Fisherman Pulling a Net, 1774. Red chalk, 19 3/4 x 14 3/4 in. (50.2 x 37.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Walter and Leonore Annenberg and The Annenberg Foundation Gift, 2006 (2006.353.1)

Rachel High: As you just suggested, drawings made by painters are often thought of as preparatory, but the catalogue and exhibition show that Fragonard considered many of his drawings stand-alone works. Could you speak to the importance of drawing in his output?

Perrin Stein: Drawing was very important and a major part of Fragonard's work, but he also worked at a time when the place of drawing in society was undergoing major change. In the mid-18th century you see significant growth in public auctions and in the way people buy and display drawings. A broader swath of society starts to collect drawings, and more of them start to frame them behind glass and hang them on walls. This is a big shift from earlier times. It's not just Fragonard rethinking what a drawing is, but the culture at the time starting to value them more. They appear with increasing frequency in the biannual salons at the Louvre; they're exhibited and talked about. For many of Fragonard's works that you see in the book, there was never any painting in mind. The drawing is the end product.

Fragonard's drawings tell us more about his working process than his personal life. Left: Jean Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732–1806). Draftsman in a Trellised Garden, ca. 1770–72. Black chalk, 14 15/16 x 9 13/16 in. (38 x 25 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.626)

Rachel High: The chronology at the front of the catalogue emphasizes how important current events were to the perception of Fragonard's work. How did the politics of the day factor into this perception?

Perrin Stein: That's a very tricky subject, because Fragonard lived at an incredibly interesting moment in history. He was born at the height of the Rococo, during the reign of King Louis XV, and he lived through and beyond the French Revolution. The dating of his output has been very problematic and continues to be so. He doesn't date his works very often, but scholars think he probably stopped painting and drawing around the time of the Revolution, due in part to the fact that in 1788—one year before the upheaval began—his only daughter died as a teenager, a very tragic event.

Also, stylistically there was a big shift leading up to and at the time of the Revolution when Neoclassicism became more dominant. Neoclassicism was very different from Fragonard's exuberant, more Baroque-inspired style. Fragonard's family left Paris during the Revolution but came back a few years later. When Fragonard returned to Paris, Jacques Louis-David, his friend and neighbor, got him a job at the newly founded museum that would become the Musée du Louvre. He worked as kind of a curator and administrator there for the last decades of his life while aiding the careers of his son, Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard, and his sister-in-law, Marguerite Gérard, who were both young artists. We can speculate on the exact reasons he stopped working, but he did live at a moment when there was a gigantic shift in style and patronage.

Depictions of the leisure class like this one became unpopular during the French Revolution. Right: Jean Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732–1806). The Husband-Confessor, ca. 1770. Brown wash over light black chalk underdrawing, 8 1/8 x 5 9/16 in. (20.6 x 14.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Lesley and Emma Sheafer Collection, Bequest of Emma A. Sheafer, 1973 (1974.356.44)

Rachel High: You wrote about Fragonard's drawings briefly in the 2009 Metropolitan Museum Journal. What inspired you to organize this more comprehensive book and exhibition?

Perrin Stein: I've loved this artist for a very long time. I started graduate school with an interest in contemporary art, but I slid backwards a few centuries because I started to work with the man who became my advisor, Donald Posner, whose focus was on Baroque and Rococo art. I wrote my master's thesis on Fragonard. Around that time, The Met partnered with the Louvre to mount an amazing retrospective exhibition in 1988, and I had a seminar class with Donald Posner and Katherine Baetjer, a curator in the Department of European Paintings here at The Met. The class took place in the galleries and I spent a lot of time there, so Fragonard was always an important artist to me. I like artists who are expressive and brushy and spontaneous, and he's really a prime example of that.

I did focus on Fragonard occasionally over the years, but I think it's a great privilege and opportunity to come back to an artist that you worked on a lot when you were younger after a period of time has passed. Invariably you see things differently. In this case, there's been incredible movement in the scholarship of the period. One big difference is scholars' growing interest in the communities these artists lived in, practices of collecting and the art market, as well as their friendships with collectors and with other artists. All the writing that my fellow art historians have done over the intervening decades has really helped me look at Fragonard anew in this catalogue.

Related Links

Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant—Works from New York Collections, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 8, 2017

The Met Store: Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant

Rachel High

Rachel joined the Publications and Editorial Department in 2014 where she has previously held the roles of Publishing and Marketing Assistant and Assistant for Administration. She manages the MetPublications website, the Museum's text licensing program in all languages, and the @MetPubs Instagram account. In addition to her work marketing The Met's titles, Rachel also consults on Museum co-publications and the Costume Institute catalogues. She has been a speaker at the National Museum Publishing Seminar and is an organizing member of the International Association of Museum Publishers. She holds a B.A. in Art History from New York University and an M.A. in Art History from Hunter College. Her own research centers on the intersections of art and publishing.

Selected publications

“Something Else Press as Publisher.” Master’s thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York, 2020. CUNY Academic Works.