Creating Custom Storage Forms for Charles James Masterpieces

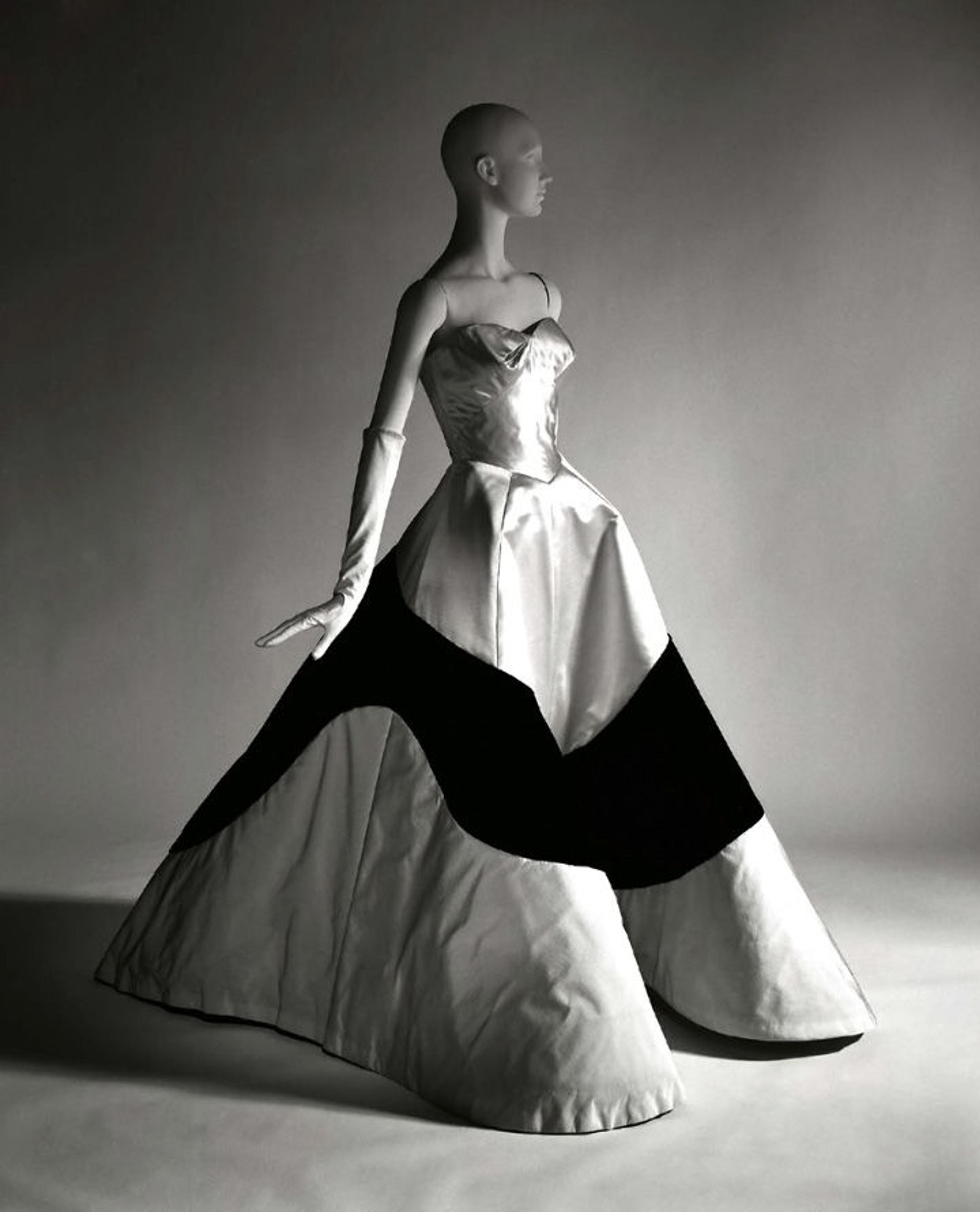

Fig. 1. Among couturier Charles James's high-profile clients were Austine Hearst, Gypsy Rose Lee, and Millicent Rogers, who adored his sculptural take on dressmaking, which included iconic shapes such as "Clover Leaf," "Butterfly," and "Swan." Above: Charles James (American, born Great Britain, 1906–1978). "Clover Leaf" Evening Dress, 1953. White silk satin, white silk faille, black silk-rayon velvet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Elizabeth Fairall, 1953 (C.I.53.73)

«Considered to be America's first couturier, designer Charles James (1906–1978) is best known for his highly sculptural dresses that are considered works of art in addition to fashionable pieces. To preserve his legacy, James strived to keep his body of work within the collection of a single institution. He encouraged his clients to donate his work to the Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection, which was later transferred to The Met's Costume Institute in 2009. Thanks to recent acquisitions of his early works and archives, The Costume Institute now has the most comprehensive collection of James's work, which was celebrated in the 2014 exhibition Charles James: Beyond Fashion.»

Since the majority of these masterpieces are strapless dresses with large skirts, storing these works presents a challenge. The gowns kept in flat storage can collapse and lose their structure—an integral part of James's designs—while those hanging can weigh nearly 20 pounds, and the tension on temporary straps sewn into the waistline can cause deformation and tears.

The Costume Institute Conservation Department took on a preventive conservation project that aimed to prevent damage to the James collection while in storage. As its name suggests, preventive conservation—or collections care—involves identifying and preventing potential hazards that cause deterioration, thus minimizing the amount of time and resources needed to treat the objects in the future. The most appropriate storage solution was to support them the way they were intended: on the body. However, storage forms are typically carved by hand—requiring hours for each form—and often yield an imperfectly fitted form.

Fig. 2. Charles James: Beyond Fashion experimented with virtual dissections involving robotics, animations, projections, and x-rays to highlight the complexity of James's dynamic designs hidden under the surface. The conservators were inspired by the high-tech visual mechanisms in the exhibition and decided to incorporate scanning technology to solve the storage issue.

The conservators' idea was to 3D scan the forms used in the 2014 exhibition as well as James's original forms to produce replicas of the 3D models, which were carved from archival foam via CNC machine, creating a proxy for the human body to sufficiently support these dresses. Though 3D scanning has been around for decades, most scans are not as perfect and exact as the technology and media may suggest. However, scanning is rapidly becoming more accessible, more affordable, and better able to produce high-quality 3D scans.

There is a spectrum of quality for 3D scanning—as with nearly every electronic product—which corresponds to both price and a learning curve. On one end of the spectrum, 123D Catch is a free smartphone app that creates a three-dimensional composite from a series of photos taken of an object from various angles. As one can imagine, the quality and detail generated is crude, but the app ultimately produces a satisfactory digital likeness in just a few minutes. At the high end of the spectrum are laser scanners and photogrammetry rigs that produce scans of the highest quality and detail. However, they can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, involve complicated setups and equipment, and require a number of specialized computer programs.

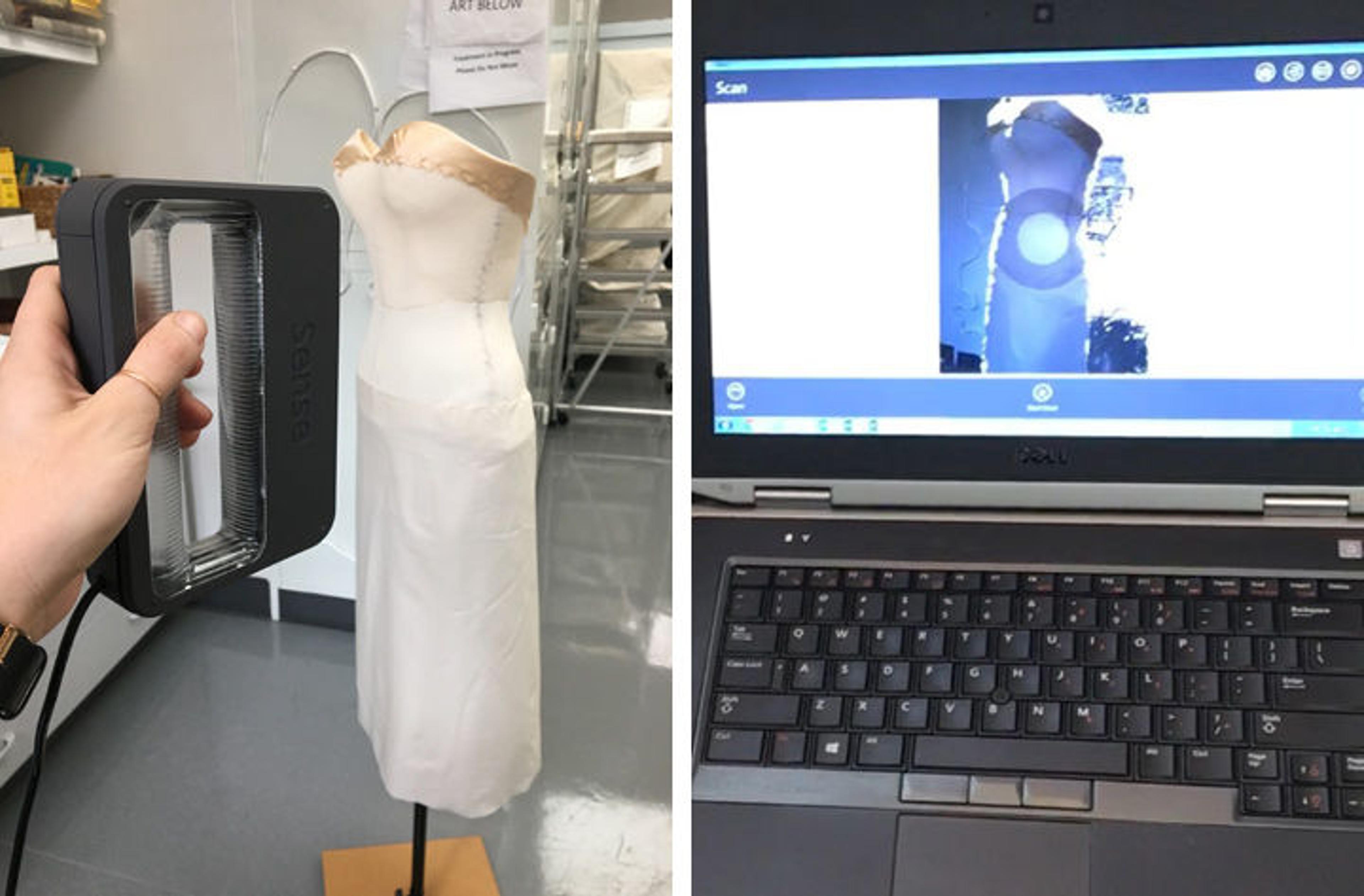

The Costume Institute's conservators wanted to show that this technique is possible without high-end equipment. Our scanner is a consumer-grade model produced by the company 3D Systems and has two simultaneous functions: one captures the colors and textures, or texture mapping; the other emits a laser to capture the shape, or geometry, of the object.

Fig. 3. Once plugged into a laptop, the handheld scanner points at the object and is moved around its entire surface from a short distance (left) to record what has been scanned (right). As the scanner is pointed at the object, a real-time image of the object appears on the screen, "recording" areas that have been scanned.

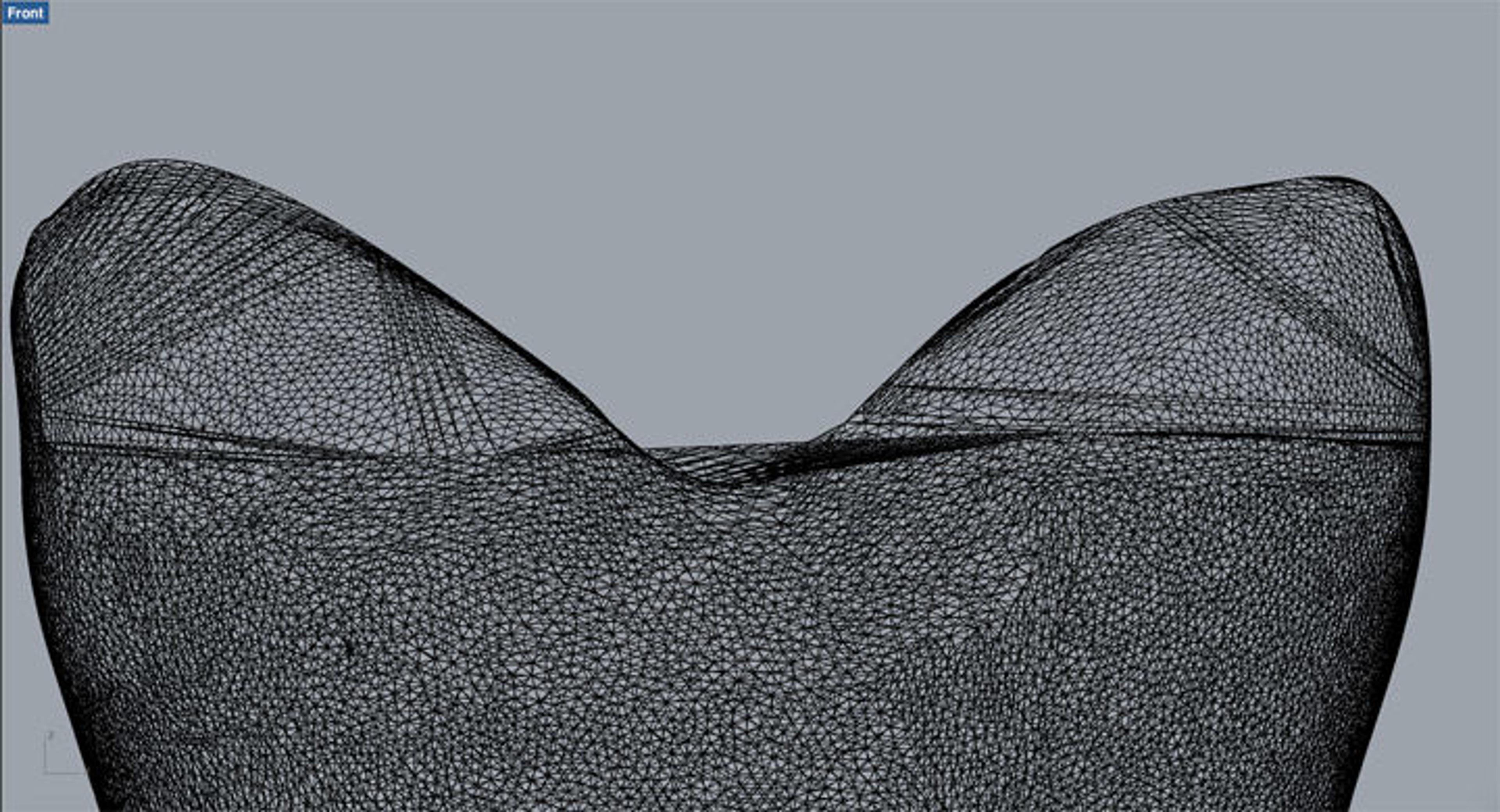

When the scanner finishes capturing an object, the scans are never entirely accurate. There are "holes" where the scanner could not register the light or texture—a common occurrence when scanning textiles—and the surfaces also appear jagged and irregular. The editing process is not unlike the process of photo editing, calling for the reshaping and refining of the surface—removing imperfections on the scan to create a smooth body form.

Fig. 4. The scanning software produces a "mesh"—a 3D model composed of tens of thousands of triangles that can be manipulated and edited.

Once the scans were edited, we sent the 3D files to a fabricator to be routed from a five-axis CNC machine. It is imperative for conservators to ensure materials that are used meet archive standards for long-term preservation. The material of choice is Ethafoam, commonly used by people in the field and a known archival product.

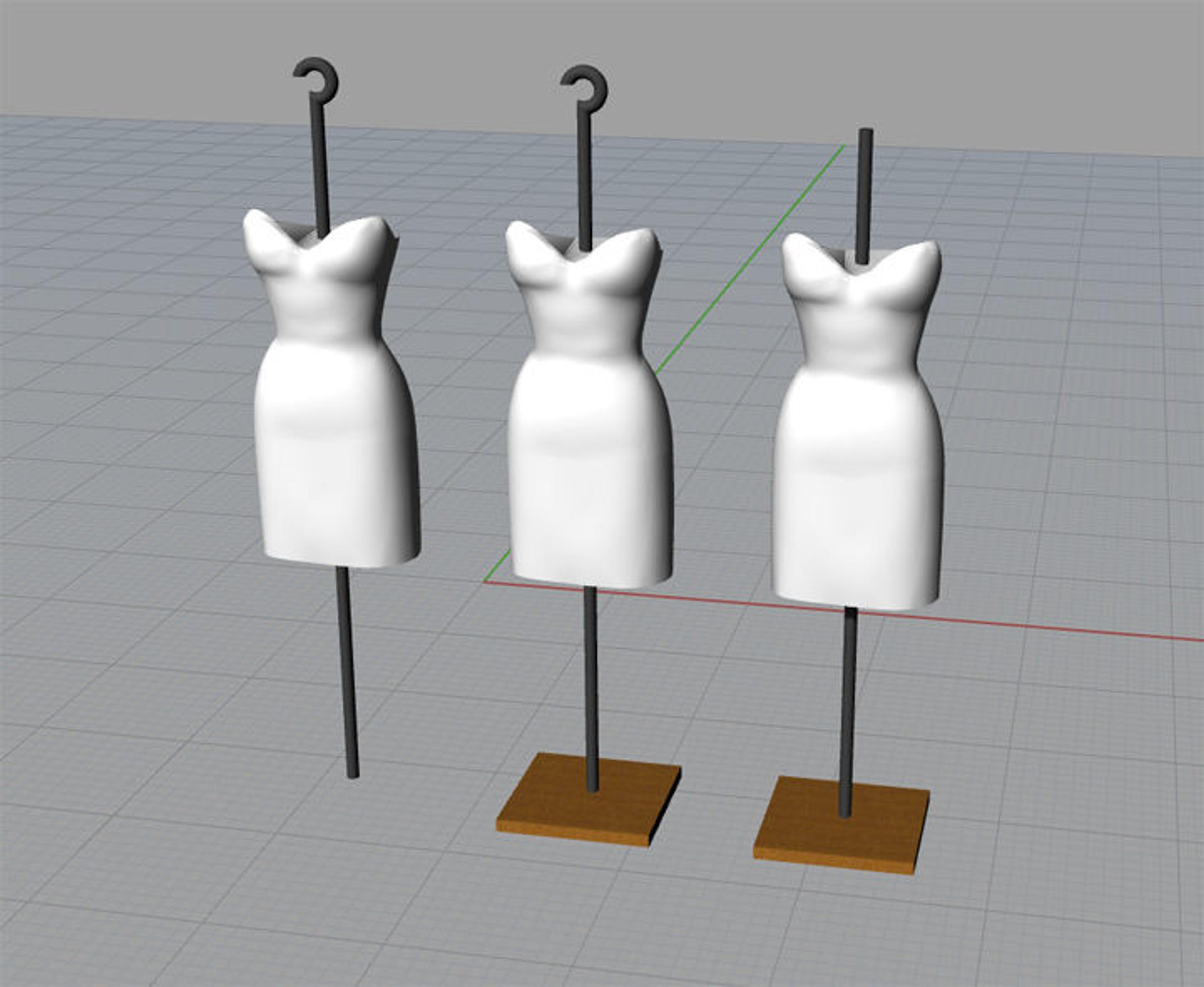

Fig. 5. The original physical exhibition form (left) and the CNC-routed product (right)

After milling, the foam replicas were outfitted with custom hooks and poles that allow the dress to be hung or placed standing on a base. The final step is for the forms to be padded with polyester batting and covered in cotton to make sure the dress contacts a plush surface.

Fig. 6. Since these forms will serve as a forever home for the gowns, we wanted to create a multipurpose design that allowed for proper handling of the dresses and pulling them from storage, as well as for traveling and photography. These forms will be able to be hung or placed standing on a base as needed.

Apart from creating a suitable storage solution for the James collection, our objective was to demonstrate an efficient and effective alternative to storage that other institutions could adopt for safely housing their collections. Museum institutions are constantly adopting technologies such as 3D scanning from all disciplines for a range of undertakings. The advantages of 3D scanning and CNC routing include accuracy and reproducibility of a form at any point, since the 3D digital files, in theory, can last forever and can be exchanged digitally. There are endless applications for 3D scanning in any field and the technology is becoming increasingly accessible.

Related Links

Met Blogs: Blog posts related to Charles James

MetMedia: Charles James: Beyond Fashion—Gallery Views, narrated by by exhibition co-curators Harold Koda and Jan Glier Reeder

Taylor Healy

Taylor Healy is a conservation intern in The Costume Institute.